It would be nice to say that I foresaw the future and planned it as it eventually turned out. But at the beginning, for every firm, the overriding question is, Can you survive?

— Bruce Henderson, memorandum to BCG partners, 1976

It is well known that business environments are increasingly volatile. They are also increasingly varied: from stable to unpredictable, from fixed to shapeable, from favorable to harsh. And conditions change with increasing speed: businesses move though their life cycles twice as quickly as they did 30 years ago.

As a consequence, the imperative for companies to match their strategic approach to the specific conditions that they face and to retune it when circumstances change is greater than ever.

Such a state of affairs naturally focuses attention on the very short term: on dynamism and unpredictability and how these necessitate agility and adaptation. Equally important, however, are the longer-term consequences.

We all know the stories of start-ups that overturned long-standing incumbents. To understand how the battle for long-term survival has changed and the implications for both challengers and incumbents, we analyzed patterns of entry, growth, and exit for 35,000 companies publicly listed in the US since 1950—with surprising

Contracting Corporate Life Spans

To investigate corporate survival and death, we focused on companies exiting the public-company pool—whether owing to bankruptcy or liquidation, merger or acquisition, or other causes.

While it can be argued that exits constitute creative destruction that benefits the economy, at the level of the individual company they are mostly unintended and associated with managerial failure. This is especially true for publicly traded companies. Some start-ups may be created for the sole purpose of being sold, but once a company has gone public, its primary goal is usually to win on its own.

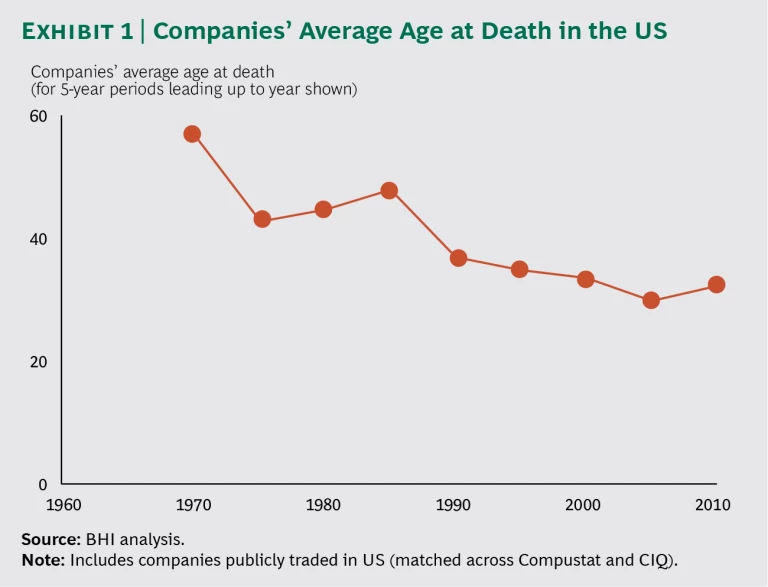

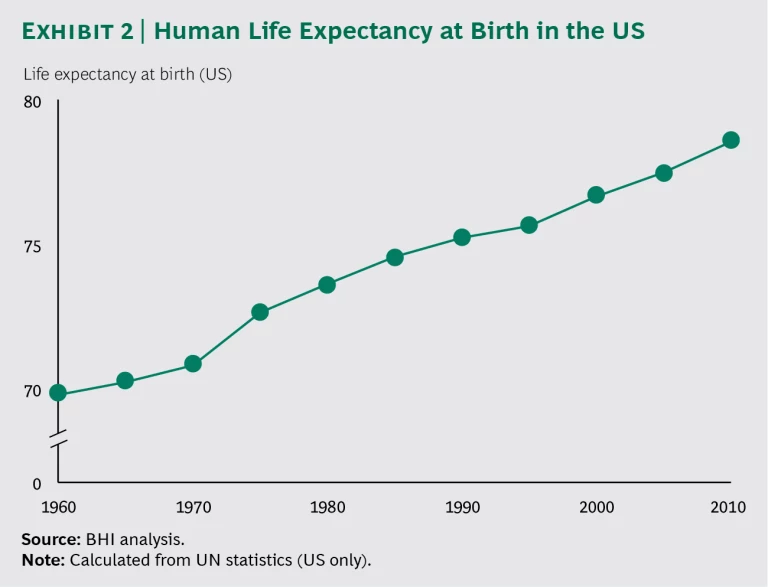

What we found is that public companies are perishing sooner than ever before. Since 1970, the life span of companies, as measured by the length of time that their shares are publicly traded, has significantly decreased. In fact, businesses are now dying at a much younger age than the people who run them. Even though companies’ average age at death and humans’ life expectancy at birth are not strictly comparable, the opposing direction of the trends is clear. Life expectancy in the US in 2010 was about 80 years, around 10 years older than in the 1960s. This is more than double the average age at death of public companies. The life span of corporations has nearly halved over just three decades. (See Exhibits 1 and 2.) Interestingly, most types of businesses in most industries are now dying younger. Only a few make it into their fifties and sixties.

So what malady has quietly befallen the corporation?

Rising Mortality Risk

Companies don’t just die younger; they are also more likely to perish at any point in time. Today, almost one-tenth of all public companies fail each year, a fourfold increase since 1965.

Why do these statistics matter to leaders? While not every manager will worry about the fate of his or her business 100 years from now, a one-in-three chance of not successfully surviving the next five years falls within typical CEO tenures and investor time horizons—and is therefore relevant to both.

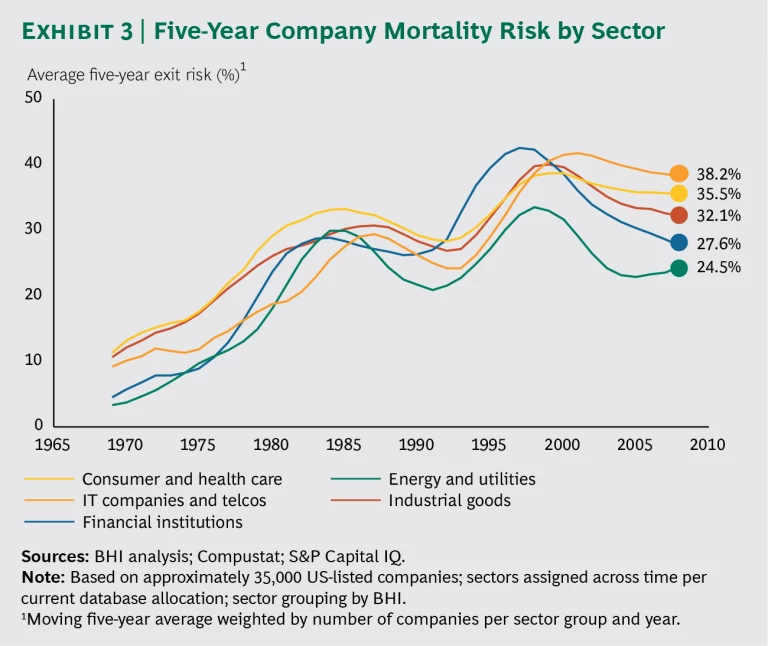

One might expect particular types of company, such as new entrants in the technology sector, to account for most of the observed shift. Surprisingly, however, our research shows that the surge in mortality risk is widespread:

- There are no safe harbors. Mortality risk grew relatively uniformly across all sectors of the economy. Only the past decade saw a slight divergence in outcomes: traditionally stable oligopolies (such as the oil and gas industry) recovered the most, while mortality remains high in more dynamic industries (such as technology).

- Neither scale nor experience is a safeguard. Mortality risk also grew for companies of all sizes and ages. While smaller companies have always faced greater risk, even the largest companies are now facing higher exit rates. Company age only began to affect exit risk in the first decade of the 2000s, when turnover plateaued for older companies but continued to grow among younger ones.

So What Happened?

We believe that a dynamic not unlike the succession sequence in forests and other ecosystems has been unfolding and driving these trends:

- In the economic and venture-capital-funding booms of the mid-1980s and mid- to late-’90s, many smaller and younger companies entered the public markets.

- These companies had a more than 25 percent higher risk of failure compared with the average company—likely owing to poorer quality (a lower bar for entry), few buffers against failure (lack of resources), and intense peer pressure (the smallest companies faced the highest competitive density).

7 7 These companies were less than 10 years old and had less than $50 million in sales. During peak mortality periods for this group, more than 50 percent of market entries were small companies. - Those that endured grew into serious competitors for incumbents, driving up the death rate among medium-size and large established companies, which were often unable to react quickly enough to the disruptions wrought by these smaller upstarts.

- Surviving incumbents then began to react by acquiring small-to-medium-size companies, again driving up exit rates in this segment while stabilizing turnover among large companies.

Take the example of Compaq Computer. Founded in 1982, it went public and shot to success extremely fast. Unlike many of its peers (Altos Computer Systems, Corona Data Systems, Eagle Computer, and Osborne Computer), Compaq survived into the ‘90s, establishing itself as a serious threat to incumbents in the computer industry. Among the much older and larger incumbents it disrupted was DEC, which was sold to Compaq in 1998. Another giant, HP, saved itself from the same fate by buying up Compaq after the company struggled through the dot-com collapse.

A Growth-Endurance Trade-Off?

We observed a surprising relationship between revenue growth and mortality: while the fastest-shrinking companies are most likely to perish, they are closely followed by the fastest growers.

In theory, decreasing life spans coupled with such a growth-exit relationship could merely indicate an acceleration in the corporate value-generation cycle. That is, companies might simply be achieving their full potential in less time.

A closer look at the data, however, reveals that the contraction of corporate life spans, on average, diminishes long-term value creation. Over the period of our analysis, the average cumulative profits of public companies declined at an even sharper rate than corporate life spans. Across cohorts, companies that died younger tended to generate lower lifetime EBIT. Longer-lived companies thus appear to create more value than fast-growing, short-lived ones.

Attaining Sustainable Long-Term Performance

Shorter life spans and diminished lifetime value constitute a strong trend—but not an inevitability. The same can be said about the relationship between growth and mortality. While it is ever tougher for companies to sustain viability and performance, there is also a broader spread of outcomes—and there are examples of companies that manage to successfully endure (such as Procter & Gamble, Johnson & Johnson, Coca-Cola, and Disney).

Many CEOs intuitively sense the challenge of accelerated mortality. Not long ago, for example, one of Asia’s emerging global-challenger companies asked us what governance arrangements would best ensure its survival and prosperity for the next 100 years.

So what can corporations do now to strengthen their long-term resilience without undermining performance? We have a number of suggestions based on our own research and the work of others on systems resilience.

Detect early-warning signals. The bare-minimum condition that will enable a company to adjust to changing circumstances is an external orientation and an awareness of change signals and their significance. The dominant logic that sustains success in slow-moving environments can easily become a mental filter preventing corporations from seeing threats to their viability. Similarly, when a company focuses on rapid change in a volatile environment, it can easily miss more slowly unfolding signals that indicate vulnerability in the longer term. Such an external orientation is as much about mind-set as it is about acquiring crucial information before it is too late.

Adapt your strategy to your environment. Imperative to safeguarding the future is surviving the present. Today’s great variety of business environments means that the same approach will not work everywhere; for example, the planning routines of classical strategy will not work in dynamic and unpredictable industries. Our research confirms that companies that match their strategic approach to their specific environment survive with the highest total lifetime value.

Run and reinvent. Environments are not only more diverse, they are also more dynamic than they were in the past, meaning that circumstances change much more rapidly and unpredictably. It is therefore essential not only to get the match right between the situation and the approach to strategy and execution, but also to ensure that the company can regularly retune itself to changing situations. Most companies today need to both run and reinvent themselves continuously, in each part of their business.

Aim for resilience on all time scales. While immediate business risks should not go unaddressed, increasing dynamism across industries may have caused many companies to adopt an excessively short-term focus. This is reflected in the recent emphasis on achieving agility and adaptability, as well as in the growing tendency to assess leaders in terms of annual or even quarterly performance. While all these measures promote short-term survival, they can also lead to the neglect of longer-term horizons. Our research shows that companies need to be resilient on all time scales. Put another way, they need to be able to sustain their adaptiveness in order to avoid becoming “disposable” corporations.

But don’t confuse persistence with performance. While company life span is an indicator of total lifetime value, simply enduring does not guarantee increased value creation. If a company cannot achieve sustained performance, it shouldn’t persist just for the sake of it. A successful exit may be better than languishing and slowly burning up resources.

Renew Your Governance Model

How can leaders ensure resilience well beyond their own tenures in the face of circumstances that cannot be anticipated? In the longer term, the key lies in building the right sort of governance model. This means setting up the company’s board structure and decision mechanisms with a view to endurance. We have identified four key governance principles that promote longevity:

- Cohesion. Avoid implosion. Align internal and external stakeholders around a clear and common mission and pay attention to succession planning.

- Prudence. Avoid overextension and vulnerability to infrequent but severe risks. Create a modular structure with buffers to prevent the escalation of shocks; focus on long-term health, not immediate TSR; and stress test your plans against 10- or even 100-year risk events.

- Adaptiveness. Avoid being made obsolete by change. Implement a culture of information gathering, experimentation, selection, and iteration; strive to harness a diversity of perspectives.

- Embeddedness. Avoid becoming an object of external (legal or social) sanction. Foster transparency, connectivity, and co-evolution with your company’s social, cultural, and natural environment. Bake sustainability principles into your business planning.

Against an increased risk of accelerated mortality, leaders who think on multiple time scales—and make sure that their organizations do, too—can defy the odds and ensure longevity and prosperity for their enterprises.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.