There could not have been a clearer sign that ING’s change was for real. Early in 2008, the Dutch retail-banking unit moved into its own new headquarters building, cementing the union of ING Group’s two previously separate banking units in the Netherlands: ING Bank and Postbank.

Related article: Changing Change Management: A Blueprint That Takes Hold

A few months earlier, the bank had begun to integrate functions such as marketing and product management. As part of its overall change program, ING had carefully thought through the order in which its two banks’ functional units would be joined, reasoning that the strategic thinking needed to entrench change across the newly unified organization would be reinforced best if it were couched in terms of what ING’s customers wanted over the long term.

ING’s change program was an uncommon one: the merger of two internal units not dissimilar in operation and sharing the same overarching cultural traits. Yet those factors would make the process as challenging, in many ways, as the merger of two corporate strangers.

The group’s ING Bank operation was rooted in a strong network of branch offices, with a particular focus on small to midsize businesses. By contrast, Postbank operations were conducted almost entirely by mail, by telephone, and online. Founded in 1881 as a nationalized business, Postbank had 7.5 million private-account holders and was one of the largest providers of financial services in the Netherlands—everything from current accounts to mortgages and pensions. Privatized in 1986, Postbank became part of the structure of the organization that, four years later, would become ING Group. In 2007, the group announced that it would merge its daughter ING Bank with Postbank, forming a single brand.

Easier said than done. The corporate culture and the familiarity, on many levels, that the two banks shared meant that crucial aspects of merger transactions were in danger of being taken for granted. Decisions that in more conventional mergers would be assessed objectively were at risk of being made on the basis of “gut feel.” Moreover, the ING Group had not been through a postmerger integration in many years. It quickly became apparent that ING needed to apply a structured process to the integration.

The financial services provider started out on the right foot by putting in place several elements that would underscore executional certainty. There was an emphasis on transparency around each specific program in the portfolio of initiatives, as well as around the overall effort. Rather than starting with a gap analysis—a conventional approach in such situations—the executive leadership team kicked off by focusing on the shape of the yet-to-be-merged company, providing a single, bright beacon around which to rally people from both Postbank and ING Bank.

Members of the top team spent a significant amount of time preparing for the change. In the first of their many meetings to ensure that all board members would consistently “radiate” the desired behaviors, the top team convened for three hours to decide how to apply the defined values and behaviors to themselves personally and as a team.

The executives also defined objectives for managing the business and, working as a team, they created a behavioral action plan, defined what the team would do differently from then on, pinpointed the visible evidence, and agreed on how progress would be tracked. By the end of this exercise and others like it, the executives, together and individually, were entirely in alignment: they really “owned” the change.

The ING team looked into the future—further than most of the banks’ employees were used to. Instead of looking out one quarter or even one year, the projections extended nearly three years out, bolstering the solidity of the merger idea by describing the path needed to get there. Most important, very clear milestones with specific delivery dates and clear impacts were set early on, defining the pace and forcing tough decisions throughout the effort in order to deliver on schedule. In short, ING’s top executives led the charge for clarity in an ambiguous situation, so staff at both banks quickly got the message that the merger really was going to happen.

To further improve the chances of a successful integration, the ING team made sure to underpin the project with formal rigor-testing and other proven change and program-management tools. For example, detailed plans were converted into rigor-tested roadmaps that would be presented to the executive leadership team before actual changes were made. The roadmaps were painstakingly constructed to provide the top team with the means for making forward-looking course corrections if needed.

An important component of the process was implementing rule-based “traffic lights” to categorize a roadmap’s progress against completion of key milestones and against leading indicators as well as operational and financial metrics. Although at the outset, many managers balked at the rigor of the process, there was nearly universal acceptance that rigor was crucial to making change stick. Indeed, the traffic light conversation itself changed slightly as the teams debated what was needed to turn a red or yellow traffic light back to green—and what actions should follow. Through constructive debate, the managers were able to clarify aims and goals and to define appropriate actions. One outcome was that a yellow light was recognized as a signal for help, as opposed to an opportunity to shoot the messenger. Such levels of clarity helped muster the necessary support early on, often mitigating the risks of limited buy-in.

ING also placed a premium on enabled leaders—at many levels. The organization went to considerable lengths to enroll its extended leadership team in the change effort, driving accountability down through the ranks with a structured “cascading” approach that left no ambiguity about who was responsible for what.

The bank went well beyond the typical steps to ensure an engaged organization. Knowing the value of crystal-clear communication and understanding the “stakeholder” roles of the employees who would have to put the changes into action every day, the executive leadership team carefully crafted an overarching “story” that explained how the two independent banks had come to the ends of their lifecycles as independent entities and showed what the new merged bank would look like and what its value to customers would be.

A “ready, willing, and able” poll of employees revealed no shortage of readiness and willingness, but it also exposed widespread concerns about the organization’s ability to make the merger work—particularly as it would affect large IT projects. To help create confidence down to grassroots levels, the top team emphasized that change would not happen overnight: it would be a three-year journey that would follow a very structured approach.

To make the change personal for each employee, managers invested time in translating the values and behaviors into what an employee experienced every day. Everyone was given a booklet that provided simple descriptions of the new values. Managers got structured-training toolkits so that over the next few months, they would be able to help employees craft their own change-behavior plans.

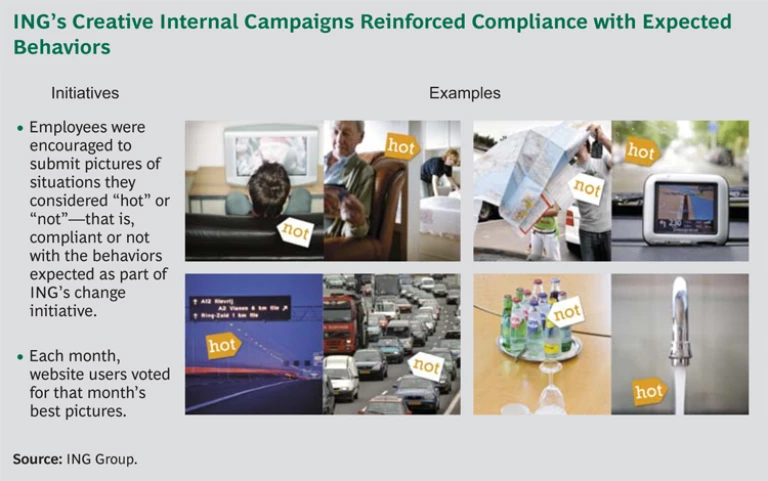

At the same time, ING created buzz with creative internal-marketing campaigns. One of the more entertaining programs involved pictures of behaviors that employees were invited to judge as “hot” or “not”—that is, “in” or “out” of compliance with the expected behaviors. (See the exhibit below.) Employees submitted their votes to a website where the submissions that best matched company values were identified.

In parallel, the new values and behaviors were continually repeated in ING’s monthly magazine, online interviews, and video clips with the CEO and board members. Frequent repetition was important in order to reinforce the messages. And interactivity (such as the hot-or-not game) served as a key engagement mechanism. But listening to employees was considered absolutely essential.

Meanwhile, ING took pains to design an appropriate governance structure with an active program management office to facilitate integration. This essential infrastructure meant determining who would have what decision rights, creating a detailed governance manual, and holding forums to thoroughly discuss the manual’s content—with a carefully designed flow of communication and action down through the ranks.

The chief measure of success for the new banking entity is not so much in numbers of new accounts, in higher revenues, or in a much lower cost base: goals such as these have been exceeded. Nor is it that ING has built a powerful and widely recognized new brand. It is simply that with customers’ needs foremost in mind, the bank has built a very effective retail-banking platform that meets customers’ expectations and creates a strong platform for growth. Announcing the intent to combine the two entities, the ING Group’s chairman at the time said, “By combining the activities of Postbank and ING Bank, we will improve the services to our customers while maintaining a strong focus on cost-effective execution. This investment will reinforce our position as the leading Dutch retail bank.”