We don’t usually think of play as being an essential part of business. Play, in a business context, looks like an optional extra: something you do after you’ve finished your work, rather than being an integral part of work itself. There are certainly many gestures toward playfulness in the modern office: bean bags, Lego corners, foosball tables, and so on. But these are more often attempts to create a comfortable working environment rather than to make the work itself more effective.

The fact that innovation productivity appears to be declining, and workplace disengagement rising, might suggest a need to become more productively playful. But it is when we look closely into the dynamics of play, and what play can do for business, that we see its true importance.

Especially when facing uncertain environments, we should understand the value of play and the steps that we can take in order to foster more genuine play in our organizations.

Why We Need Play

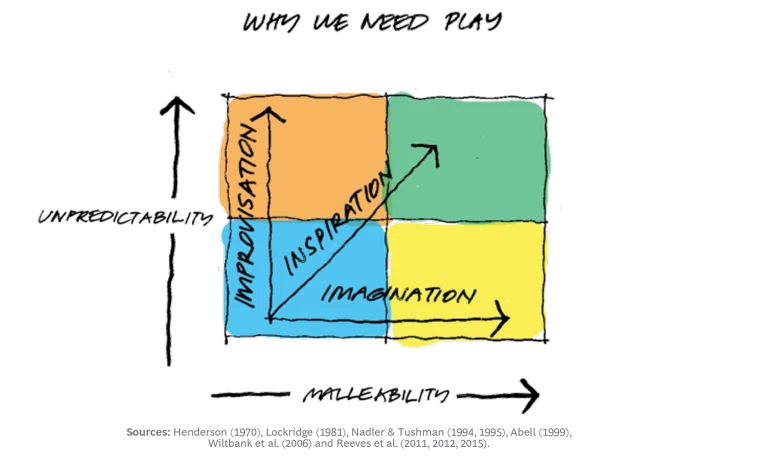

Play is an activity that can be realized in many forms. We can define it as deploying improvisation and imagination, to inspire ourselves and others toward more effective exploration of possibilities. Each of these three components—improvisation, imagination, and inspiration—is increasingly important in today’s business contexts.

Improvisation is needed the more an environment becomes unpredictable. The less we can rely on plans, the more we need the mindset and skill of improvisation, to respond rapidly to novel situations. Imagination is needed the more an environment becomes malleable: the more opportunities we have to shape patterns of demand and competition. In such open-ended situations we compete on our ability to envision new products or areas of unmet need. Inspiration is required the more we involve others, as in building and orchestrating a complex and dynamic business ecosystem. In each case, the more our environment departs from orderly stability, the more we need to cultivate play.

What Play Can Do for Us

Diving in more detail into these interconnected elements of play, let’s examine the value that play can bring.

Improvisation

Play involves improvisation, meaning doing something quickly and with minimal preparation in response to an external stimulus or internal “hunch.” Many of us will understand this personally from toying with Play-Doh as children—making shapes without much premeditation, following whatever thoughts come to mind. Psychologist Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi argues that play occurs when we do things immediately that are within our ability. The piano player improvises when she plays new chords and melodies—things she can do but might not have done before in precisely that form. In the landscape of possibility, we are exploring “nearby” moves rather than long-distance “moonshots.”

Interestingly, the invention of Play-Doh itself is an example of this in business. Play-Doh (then called Kutol Cleaner) began as a product to clean wallpaper, until the inventor Joe McVicker heard a teacher saying that kids found modeling clay too tough to manipulate. On a whim, McVicker shipped some wallpaper cleaner to the school, and the kids loved it. We can suppose he thought something like “might as well try it.” This moment illustrates a key aspect of the mindset of play. McVicker was improvising with potential applications for his product, in this case with successful results.

Google Maps also began with play. In 2003 then-CEO of Google Eric Schmidt was reportedly in a meeting discussing whether Google should acquire Picasa. But Schmidt was not paying attention; he was fiddling around on his computer with a satellite mapping tool called Keyhole. Following his own hunch and sense of excitement, Schmidt interrupted the meeting and demonstrated Keyhole. The executives forgot the official agenda and spent the time playing with the new tool. A lot of systematic activity was later required to develop a business, but the original idea came from play. To take another, historical example, the basic design of the telescope is thought to have come about from two children playing with different lenses in the shop of the inventor Hans Lippershey.

We can’t measure how many possibilities we miss when we don’t play (when we stick strictly to the agenda, or never play with the lenses), but we do know that play can lead to innovation. We also know that businesses that innovate less are less likely to succeed in the long term. Play should thus be seen as a personal, whimsical, and yet legitimate path to uncovering new ideas, ones we might not have found through more systematic, goal-oriented approaches alone.

Imagination

Another key element of play is the imagination. Australian software company Atlassian is famous for cultivating a playful, collaborative mindset among its employees. One game they play is called Premortem, in which the team is encouraged to think of terrible outcomes. “All depths of doom and despair are encouraged.” The instruction manual explicitly prompts the imagination: “Close your eyes and picture your CEO holding a press conference. A pack of hungry journalists and irate customers are in front of your building. What does she say?” They explore a landscape of dangerous scenarios.

The rationale for this kind of activity has been described by biologists, in analyzing how and why mammals play. Animals invent handicaps, or mock dangerous situations, and then try to escape them, to be prepared for real-life dangers. Thus, while the play itself is fun, it has an essential function in the long run. The underlying mental skill here is the ability to hold in mind what is not true. Often in business we are much more comfortable with questions of the form “What can my bank do next year?” versus “What could a bank be (that no bank currently is)?” Play happens in the subjunctive mood—relating to what is imagined or wished. We need playful conversations to envision possible futures, negative or positive.

The imaginative aspect of play is also valuable in customer research. As the CEO of GE, Jeff Immelt emphasized the need for “imagination breakthroughs” and “dreaming sessions” with customers. If we can create the free, improvised state of play with customers, it helps us move beyond questions about existing products (what kind of chocolate someone prefers, or how they sold their last house), to what can be imagined. With the rise of virtual reality in customer research, opportunities will only increase to design imagination-spurring playful experiences, to reveal unmet and hitherto unimagined needs.

Inspiration

Inspiration is the other strand that runs throughout genuine play. The mental skill here was defined by the philosopher Aristotle, who pointed out two bad extremes in discussions: being too serious and dull, and being too frivolous—which is dull in its own way. Between these two lies a mental quality Aristotle called eutrapelia, or “good-turning”: being able to change direction playfully from serious to fun and back, engaging others in a rich but also lighthearted discussion. Somewhere between the tedium and buffoonery lies inspiration, where sparks of interesting thought arise in ourselves and spread to others.

Creating the space where inspiration happens is crucial whenever we work with others. Sharing imaginative thoughts with colleagues creates much more inspiration than one person instructing others. One well-known proxy marker of the need for more play is workplace disengagement: according to Gallup, 70% of US employees are not engaged, meaning “sleepwalking through their workday, putting [in] time—but not energy or passion.” The most important area for inspiration, however, lies in reaching out to others. If we can practice striking the right balance of playfulness in day-to-day office interactions, we can take this skill outside the corporation, in getting to know clients or building ecosystems of collaborators. When we work with external partners it is critical to be able to spark people’s personal engagement, to co-create and share ideas, since we have less control and are more reliant on the voluntary engagement of others.

Play, then, does a lot for us, whether in impromptu conversations, brainstorming sessions, unplanned tinkering with products, customer focus groups, or client presentations. Play helps us in discovering new products and markets, imagining scenarios, exploring a vision, and creating shared inspiration and ownership of ideas. The underlying mental skills are ones we need the more we face unpredictable and open-ended environments—when we need new ideas and to bring others along with us.

How to Get More Play

There is no set of instructions to guarantee effective play—to be too instrumental and mechanical about it would be self-defeating. But we can draw lessons from cultural and biological research, to identify the actions you can take as a leader, to create the conditions for more play.

1. Derisk Play

As we learn from mammalian play, a basic condition for play is that the negative consequences of action are reduced. We can improvise and imagine more broadly when we give play a break from the ordinary responses and judgments of the world. In the workplace, we should seek to create what management professor Amy Edmondson calls psychological safety: “a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone for speaking up.” Play can be odd, foolish-looking, even mischievous; it is no coincidence that Hermes was the ancient god of wordplay but also the god of trickery. We should seek to encode in our organization’s communications (our statement of values, all-staff emails, induction programs, introductions to meetings) a tolerance for what happens in playful discussions and situations, recognizing it as a somewhat wilder mode than ordinary interactions.

2. Suspend Goals

Most corporate work is rightly linked to a goal, which aligns intentions and prioritizes what we emphasize and communicate. In play we invert this. It’s interesting when intentions don’t align and minds wander off in different directions. A prerequisite for play is to suspend the idea of an objective, to allow conversation to be driven more by people’s personal impulses and imagination. Yet temporarily abandoning goals is mentally difficult. Psychological studies show that a strong predictor of adult playfulness is low levels of prudence, and yet prudence—practical judgment—is an admired virtue in business. A playful corporation, therefore, has to cultivate (and hire) minds that can cross between the prudent and the playful: from careful, goal-directed communication, to whimsical, aimless—but ultimately valuable—reverie.

3. Create Thresholds

A famous study of play, the book Homo Ludens by Johan Huizinga, notes that all cultures set aside special zones for play: “The arena, the card-table, the magic circle, the temple, the stage, the screen, the tennis court, etc., are all in form and function play-grounds, isolated, hedged round, hallowed, within which special rules obtain.”

4. Start with the Personal

Whether we’re in a designated space or not, it can be hard to find a trigger that kicks off play. For a hint, we can look to the Greek word for play, paidiá, which is derived from paîs, the word for child. Children have a key lesson to teach us here: when they play, they allow their personal, spontaneous feelings to guide what they say and do. As adults, this is usually more of a challenge. Much of corporate work is impersonal: there is a rational way to proceed; we start with the problem or the logical beginning. In play, the starting point is personal: we must bring our impulses and imaginations to the engagement. Rather than thinking what is best or right to say, we must ask ourselves, “What do I really feel?”—even if the answer is unusual. That is, a good way to kick off play is to say something spontaneous and idiosyncratic. We can lead by example here but also embed this practice in shared working norms, eliciting people’s genuinely personal reactions and feelings, moving interactions temporarily from the rational to the impulsive.

5. Have Patience with Play

Play involves unpredictable, improvised moves from one thought to another and multiple divergent imaginations. Progress is unclear—you wander around for a bit, follow interesting things. At the end of one burst of play, there may be no outcome, or it might not be obvious. Perhaps next time you will stumble on a great connection; perhaps something half came to light that will become clearer later. These dynamics don’t sit well with a push to assess the outcomes of each hour of work. But the value of play is in the long run. Play may not show returns on every occasion, but will bear fruit over time, as a generator of ideas and inspiration and as a forum for practicing important mental skills. To build a more playful corporation, we first need to see and convince others that play is a long-term commitment.

Play often seems marginal to work, because work is based mainly on goal-directed action and efficiency. But play is not the opposite of work— that’s leisure. Play is rightfully seen as part of productive work. Doubling down on efficiency without a commitment to play risks creating institutions less able to unlock much-needed human capacities, like the ability to improvise, to imagine, to inspire others. We should take play seriously—with a sense of irony—as part of intelligent business strategy.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.