School districts in the U.S. spend $18 billion on teacher training each year. Most often, in terms of the total hours spent, the format for that training is collaborative professional development, a form of training in which teachers work together in groups to improve their teaching. These groups are often called professional learning communities (PLCs). Two-thirds of U.S. teachers now report spending time in PLCs.

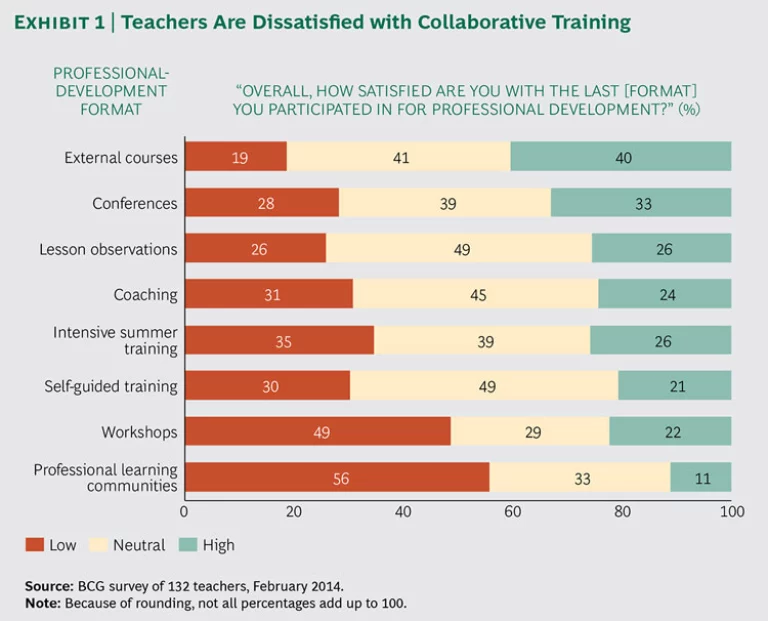

So far, the results of such collaboration have been poor. The intentions are good, but the implementation is not: teachers are even less satisfied with collaborative professional development than with the “sit and get” workshops that collaboration was intended to replace, according to a

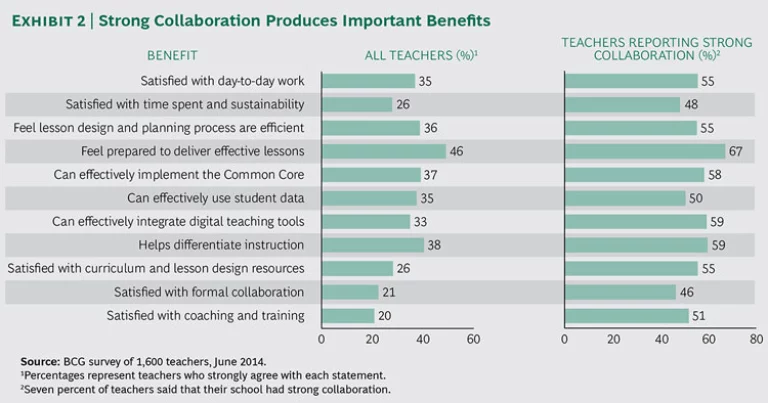

Districts must begin to close the gap between the engaging, relevant, and hands-on training that teachers and administrators say they want and the reality of disengagement with collaborative training on the ground. The benefits: teachers who have positive collaborative-professional-development experiences say that they work smarter and that their jobs are more sustainable, and they feel that they are better able to address the many challenges they face in implementing Common Core standards, differentiating instruction to meet student needs, and more efficiently using data and technology. They are more engaged, and studies show that a feeling of engagement helps good, difficult-to-replace teachers stay in the profession. Ultimately, the evidence suggests that better implementation of collaborative training could add up to better outcomes for students.

Effective Collaboration: The Missing Ingredient in Teacher Training

The traditional design of schools in the U.S. tends to isolate teachers and make collaboration difficult. A 2012 survey by Scholastic and the Gates Foundation found that teachers spend just 3 percent of their day collaborating with their colleagues.

Even when they do collaborate, teachers often feel disengaged. More than half of the teachers we surveyed are dissatisfied with the collaborative training they receive through PLCs. (See Exhibit 1.) It seems to them like duty, not development.

Teachers point to a number of problems with current collaborative training initiatives:

- A Lack of Dedicated Time to Collaborate. Fifty percent of teachers responding to our survey said this was a significant challenge. Even when time is allocated, it often devolves into an administrative staff meeting. “They give us the latest information about things like testing and legal requirements but little about instruction,” said one teacher.

- Poorly Planned or Poorly Executed Collaboration Efforts. Some teachers told us that collaborative training too often feels like a “social hour.” As one respondent, speaking about PLCs, put it: “You need an agenda and rules.” We also heard from teachers weary of collaborative training that is not truly collaborative. “Don’t read PowerPoint presentations to me,” said one.

- A Disconnect with Teaching. Many teachers think of current professional-development opportunities as mere items in the “laundry list” of things they have to do, like paperwork and attending meetings. Collaborative training doesn’t meet their need for learning that is directly relevant to today’s or tomorrow’s lesson.

- A Lack of Preparation for Changes in the Job. Most of the teachers we surveyed reported that current training programs are not helping to prepare them to use technology and digital learning tools and analyze student data to deliver personalized instruction.

In general, though, teachers want to collaborate. When we asked teachers about the work activities they want to spend more time on, “formal collaboration with other teachers” ranked third of 11 activities, behind “mentoring students” and “more personal breaks.” Likewise, when we asked about the strongest enablers of effective professional development, teachers selected “collaborative planning time,” behind “autonomy” and “access to pertinent resources.”

Roughly half of all the teachers we surveyed reported that collaborative small groups are helpful in discussing one another’s experiences and frustrations. On average, though, teachers do not find that collaboration actually helps them do their jobs. But the subset of teachers who report being highly satisfied with collaboration offer a stark contrast: they say that collaboration not only improves their relationships with their peers but also improves their teaching. More than 60 percent of these highly satisfied teachers say that collaboration helps them plan specific lessons, identify daily and weekly learning objectives, align on curriculum standards, and develop teaching skills and content knowledge.

In short, teachers overwhelmingly want to get better together. But they also want to work together in ways that constructively address the challenges of day-to-day instruction.

An Action Plan for Better Collaboration

Migrating to a more effective collaborative model is a major change for a school district. And change is difficult: approximately 70 percent of change initiatives, across industries and in both public and private organizations, fail. But our work in change management and our extensive research with teachers and administrators reveal several ways to address the issues that currently stymie collaborative-training efforts:

- Provide sufficient time to collaborate. Teachers say that they need regular, dedicated time to work together and that teachers and administrators must protect that time from meetings and administrative demands.

- Foster strong leadership. Teachers have told us that they want autonomy and want to help shape and direct training. They feel that teachers should help lead collaborative professional development, but they aren’t necessarily opposed to administrator involvement. In fact, our research found that teachers were slightly more satisfied with their PLC if it was led by both a teacher and an administrator.

- Develop clear objectives. Collaborative professional development is a serious endeavor worthy of thoughtful planning and execution. Effective groups develop an agenda for meetings, and follow it. And they develop and stick to meeting protocols.

- Train teachers to collaborate. Effective collaboration rests on skills—facilitation, active listening, giving and receiving feedback, resolving conflict—that need to be developed in most people. Helping teachers to be effective leaders—and participants—will improve group dynamics and enhance the value of training and ensuing collaborations.

- Embed collaboration in teachers’ day-to-day work. A framework or an exercise that simulates work is not sufficient; teachers want a working session that provides tangible takeaways that they can put to immediate use: a lesson plan, a strategy for students who they are struggling to reach, a teaching technique to try tomorrow.

The actions presented above hold strong promise for improving collaborative teacher training, but they cannot be implemented without systemic changes. Districts need to embrace innovation and continuous improvement—they must cultivate an openness to trying new approaches and tools, measuring their impact, and fine-tuning execution over time. (See “Digital Resources for Collaborative Teacher Training.”)

DIGITAL RESOURCES FOR COLLABORATIVE TEACHER TRAINING

In addition to tapping in-person opportunities to change the nature of teacher training, teachers can take advantage of a number of promising digital resources to collaborate in their own development. “Thirty years ago, I would spend all weekend long doing this myself,” said one teacher who participated in our research. “You don’t have to be so isolated anymore.”

Our research in collaboration with the Gates Foundation found a variety of ways that teachers use the Internet—not just to find and share teaching resources but, equally important, to connect with one another and get better together through collaboration.

- Teaching Channel provides hundreds of teacher-to-teacher demonstration videos and articles sharing best practices, as well as Teaching Channel Teams, an interactive collaboration platform that districts can use for professional learning. Schools are using Teaching Channel to introduce innovative approaches to foster collaborative training. For example, at the Academy for Urban School Leadership in Chicago, mentor teachers record videos of novice teachers who are part of a one-year training residency, edit the videos to highlight areas for improvement, and upload them to a common platform using Teaching Channel to provide feedback.

- Edmodo is a popular online platform with a wide array of products that foster greater collaboration, including peer-based communities and a marketplace of teaching apps developed by third parties. The fast-growing company now boasts more than 50 million teacher, student, and parent users.

- Share My Lesson’s slogan is “by teachers, for teachers.” The online platform has more than 300,000 free teaching resources created by teachers for others to use and a collection of forums to “discuss, debate, or let off a bit of steam.”

- Edthena is a video-based collaboration platform that lets teachers upload videos of their lectures; other participating teachers can watch the videos and provide remote feedback and coaching.

- Teachers also use more mainstream Web and social media tools such as Google Classroom and Pinterest to share ideas and work collaboratively. Google Classroom has a suite of tools that seamlessly integrate Gmail, Google Docs, and Google Drive to help teachers create, edit, and share lessons and assignments with other teachers and with students. And Pinterest has become a popular resource for teachers to “pin” their favorite lesson plans or classroom activities for other teachers to use.

These innovations just scratch the surface, and new digital products and services for educators are emerging every day. The opportunity to engage educators in cultivating new ideas and solutions is behind the online Redesign Challenge, a Gates Foundation–supported collaborative effort designed to bring educators together to “reimagine breakthrough innovation in teaching and learning.” Its first challenge aims to help make professional-development videos more relevant and useful to educators.

Leaders who are serious about facilitating and sustaining change need to transform their organizations in two fundamental ways:

- Across Departments. To be most effective, professional development cannot be the province of a single department. Rather, multiple departments must work together closely to support teachers. Those in charge of training, curriculum and instruction, teacher evaluation, scheduling, and technology will need to communicate and collaborate effectively. The school day or calendar might also need to be adjusted to allow teachers the requisite time to collaborate and share ideas.

- From the Superintendent to the Front Lines. Administrative support from the district level must cascade down to the classroom, and teacher input must flow back. This means clearly articulating goals and guiding principles, empowering school leadership with flexibility to customize implementation for their context, and continuously soliciting and incorporating teacher feedback.

As these points illustrate, implementing effective teacher collaboration system-wide will require effective collaboration in the district office as well as between district and school.

The Compounding Benefits of Collaboration

Collaborative teacher training, done right, yields significant benefits. For one, when teachers are able to collaborate productively with one another, their overall job satisfaction improves. Our research shows that teachers who are in settings featuring strong collaboration—defined as having formal collaboration time built into the schedule, shared instructional-planning responsibilities, and a teacher-reported positive culture of collaboration—report satisfaction with their day-to-day work 20 percentage points higher than teachers who are not in these environments.

While we acknowledge that teacher satisfaction and self-assessments are not the same as effectiveness, and that more research in this area needs to be done, we maintain that heightened job satisfaction can yield downstream benefits: higher retention of good teachers, better teaching abilities, and improved student outcomes.

Gallup research on employee engagement, for example, shows that when employees are engaged in their work, they are more productive and turnover is lower. When they are not, they often leave. TNTP, an education nonprofit, estimates that nearly 10,000 “irreplaceables” leave the 50 largest school districts each year, with many citing a poor school culture, among other factors that collaborative professional development could address. When one such irreplaceable teacher leaves a low-performing school, TNTP estimates, it can take as many as

In our survey, two-thirds of teachers who experience strong collaboration at work strongly agree that they are effective teachers, compared with less than half of all teachers. And while almost 60 percent of teachers in collaborative environments strongly agree that they could effectively implement new concepts such as digital teaching tools and the Common Core, only about 33 to 37 percent of all teachers feel this way, respectively. (See Exhibit 2.)

If good teachers are more likely to continue teaching and are significantly more confident in their abilities, including their ability to deal with the changing nature of their jobs, we predict that students will enjoy tangible improvements in learning and outcomes.

Ultimately, improving teaching skills through collaboration is a win-win: teachers and administrators agree that collaborative training is the right thing to do, and research suggests that it will ultimately improve outcomes. But collaborative training requires focus and effective execution to live up to its promise of producing better work environments for teachers, more-effective teaching, and an improved education for students.