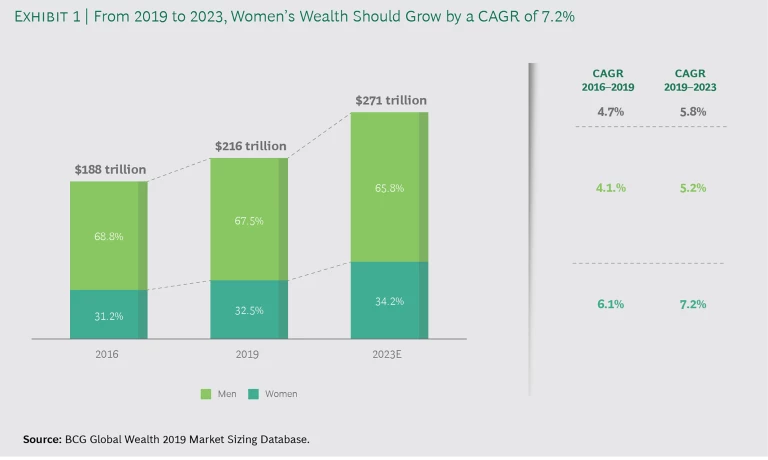

With a third of the world’s wealth under their control, women have become a sizable economic force. They are increasing their wealth faster than before—adding $5 trillion to the wealth pool globally every year—and outpacing the growth of the wealth market overall.

Despite the increasing power of their purse strings, however, women remain largely underserved by the wealth management community, according to a comprehensive global study by BCG. Too many banks and firms rely on broad assumptions about what women are looking for, resulting in products, services, and messaging that can feel superficial at best and condescending at worst.

Fortunately, our research shows that wealth managers can turn their approach around. By recognizing that the women’s segment is not a marketing opportunity but a massive business opportunity—and by personalizing their approach to meet the specific needs and priorities of individual clients, regardless of gender—they can make the ’20s a defining decade for women in wealth.

Women Control 32% of the World’s Wealth

Women are amassing greater wealth than before, and that share is likely to grow significantly in the years ahead.

Even though the COVID-19 crisis will undoubtedly have near-term effects, the larger trends in women’s evolving role in the world will continue. Our pre-COVID-19 scenario anticipated that the total wealth pool owned by women would rise to $93 trillion by 2023. Factoring in the effects of COVID-19, however, we believe that three different scenarios could emerge:

- V-Shaped Scenario. Gross domestic product falls steeply, with some displacement of output, but growth eventually rebounds. Under this scenario, women’s wealth would recover from any short-term hit and rise to $93 trillion by 2023—a CAGR at 7.2%—effectively remaining on a par with our pre-COVID-19 projections.

- U-Shaped Scenario. Economic shocks persist, with some permanent loss of output despite resumption of the initial growth path. Under this scenario, we project women’s wealth to grow to $85 trillion by 2023—a CAGR of 4.9%.

- L-Shaped Scenario. Economic impacts are severe enough to cause structural damage to the labor market, capital formation activities, or the productivity function. Under this scenario, we project women’s wealth to grow to $81 trillion by 2023—a CAGR of 3.7%.

In sum, although the COVID-19 crisis has taken a tragic toll, its economic impacts will gradually lessen as the crisis abates. Overall, our pre-COVID-19 reporting is likely to hold, and we expect women’s wealth to outpace global wealth growth over the next several years.

Overall, we expect women’s wealth to outpace global wealth growth over the next several years.

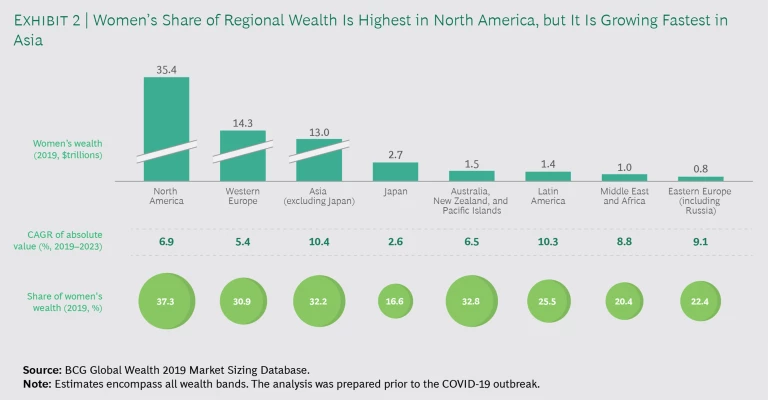

How women generate their wealth varies by region. Women in North America hold the largest share of wealth (37%) relative to the total regional wealth pool. (See Exhibit 2.) They also hold the greatest volume of assets in absolute numbers ($35 trillion). Women in the region comprising Australia, New Zealand, and Pacific islands hold the next-largest share at 33% ($1.5 trillion), followed by Asia exclusive of Japan at 32% ($13 trillion) and Western Europe at 31% ($14 trillion).

From 2019 to 2023, North America will continue to have the largest concentration of female-owned assets, with women’s wealth in the region projected to rise at a steady CAGR of 6.9%, although this rate is slightly lower than the anticipated global average of 7.2%.

Nevertheless, Asia exclusive of Japan will be the fastest-growing hub of wealth creation for women. If growth in women’s wealth continues there at its current heady 10.4% annual rate, Asian women will add more than $1 trillion per year to their total wealth over the next four years. A continuation of that stunning trajectory would see Asian women holding more wealth assets than any other region in the world except North America by 2023.

Japan is the notable exception to the trend in Asia. With a total wealth share of just $2.7 trillion, Japanese women lag behind other industrialized nations in investable and noninvestable assets. One reason for this situation is that Japanese women face more barriers to economic inclusion than their global peers do. The obstacles include relatively limited opportunities for advancement, as comparatively few women have positions in the country’s managerial ranks. In addition, Japanese culture places primary responsibility for family and domestic care on women—and as a result, women exit the workforce earlier than men and have a harder time returning. Owing to these entrenched factors, men control more than 80% of the nation’s wealth. Even so, relative to the rate of absolute wealth growth in Japan, women will significantly increase their share of wealth during the period from 2019 to 2023 (by 2.6% CAGR, compared with 1.2% for men and women combined). But clearly their wealth is starting from a much smaller pool.

Western Europe, too, is likely to experience much slower growth in women’s wealth over the next four years than other advanced markets. That tepid forecast will translate into a wider gap in women’s wealth between Western Europe and its largest peers by asset volume, North America and Asia.

Elsewhere, Latin America, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East will see strong growth from 2019 to 2023, albeit on a much smaller asset base. The expected rise in women’s wealth in the Middle East is especially noteworthy. Greater political and economic stability across the region and improving health-care and educational access for women are fanning the expected 9% CAGR. Girls’ rates of primary and secondary school participation are now similar to boys’, and women outnumber men at the university level in 15 of 22 Arab countries. Women are making the most of these educational opportunities. In Bahrain, for example, girls consistently make up the majority of top-ten high school graduates, based on academic performance.

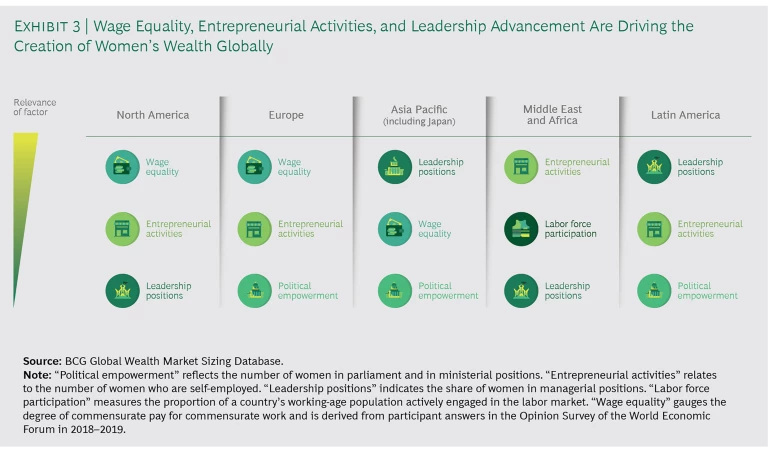

The opening up of the Middle East is further evidence that expanded access to education and health care can have powerful and positive implications for women. Labor force participation, leadership positions, and political empowerment also play important roles in economic advancement. (See Exhibit 3.) Our data shows, however, that these indicators have developed at different rates. Labor force participation has grown much faster than wage equality, for example. Of all the criteria examined, wealth creation for women is most highly correlated with holding high-skilled jobs. For example, women account for roughly 50% of high-skilled workers in North America, compared with around 20% to 40% in most developing countries.

Women Invest Differently, but Not in the Ways Most Wealth Managers Think

Women used to be an afterthought in the wealth management industry. Even with the increasing prominence of women in the overall picture of global wealth, many banks continue to uphold historical social norms that regard men as the primary financial decision makers. Those attitudes are changing, but too many women still feel underserved. Although banks and wealth management firms frequently offer products designed for women, the gender distinctions are often superficial or reflect outdated assumptions about women’s role in driving wealth and their interest in managing their financial affairs.

The gender distinctions in financial products designed for women are often superficial or reflect outdated assumptions about women’s role in driving wealth.

To understand how gender influences wealth management decisions, we conducted a global investor survey, capturing input from 300 affluent and high-net-worth individuals across genders, supplementing this research with wealth industry interviews.

Five key themes emerged from our research.

For Women, Wealth Is a Means to a Number of Ends, Not an End in Itself

Globally, women continue to bear disproportionate responsibility for family priorities. Shona Baijal, managing director of UBS Wealth Management in the UK said, “Generally speaking, women face five different challenges through their financial life journeys, compared to men: the gender pay gap, the need for flexible working conditions, maternity leave, longer life expectancy, and a lower risk tolerance.” These factors mean that women are more likely to anticipate and plan for key events and life stages. Kristy Wallace, CEO of Ellevate Network, explained, “Women are more sensitive to specific inflection points in their lives and the financial impacts that come from them.” As a result, women tend to invest to fund specific goals, whether those goals involve leaving a legacy for the next generation, supporting a postretirement lifestyle, endowing a family business, or making a social impact in their community.

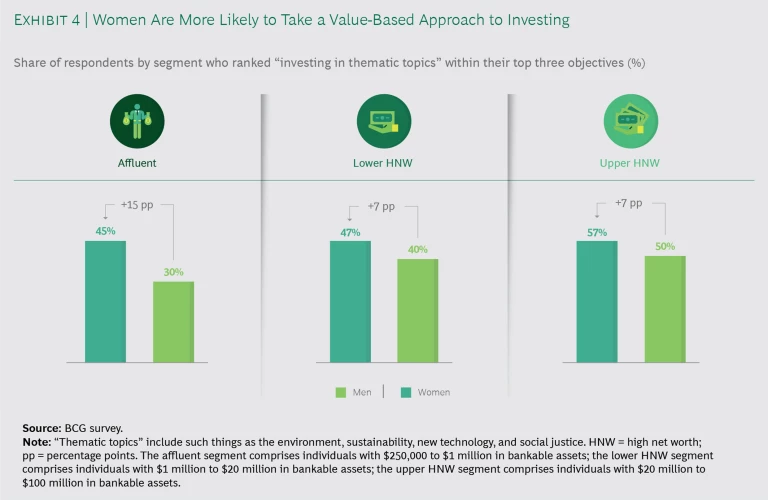

Women are also more likely than men to invest on the basis of their values, favoring funds that not only perform well but also create a positive impact, as opposed to investing solely for performance. Tracey Woon, vice chairman of UBS Wealth Management for the Asia-Pacific region, said “Women do not just want to boost the bottom line; they also want to help develop the communities we live in, by investing in education, health care, and our planet.” In our survey, 64% of women said that they factor environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concerns into their investment decisions. As women accrue greater wealth, such topics factor even more heavily in their thinking. (See Exhibit 4.) Men, by contrast, tend to place more emphasis on pure performance: 96% of males in our survey said that they invest to increase their income and that they base their investment decisions on an asset’s track record for growth and yield. Madeleine Sander, chief financial officer of the German private bank Hauck & Aufhäuser, said, “Female and male investors differ in their investment approach. While women tend to prioritize risk reduction and doing good, men place a stronger focus on historical performance and the process for individual stock picking.” Steph Wagner, director of women and wealth for Northern Trust, added, “Wealth managers continue to assume that language around performance resonates with men more than women, when actually both genders value performance. However, women are more likely to push back and ask questions to better understand its impact on their short-term and long-term goals.”

Women Make Investment Decisions Based on Facts, Not Their Gut

Although both men and women are willing to embrace risk, women tend to be more deliberative and are more averse to uncertainty. Once they have the data needed to make an informed decision, however, their investment profile is similar to that of men. Katie Nixon, chief investment officer of Northern Trust, said, “Women seek to reach their goals with a high degree of confidence. At times, this may appear as a lower risk tolerance; however, it is often a gap in information. In focusing on personal goals, women want to be armed with the right data—an articulation of the trade-offs and how an opportunity relates to them, not the market itself.”

The fact-based approach seems to pay off. Although women may not invest as much or as often as men, they often outperform men when they do. Shona Baijal said, “Once women are investing, research shows they are more diligent than men, more agile in changing markets, and more optimistic about the long term.” When Fidelity Investments examined the results of 8 million of its male and female retail clients in 2017, the analysis showed that women, on average, earned nearly 1 percentage point more per year than men.

Although both men and women are willing to embrace risk, women tend to be more deliberative and are more averse to uncertainty.

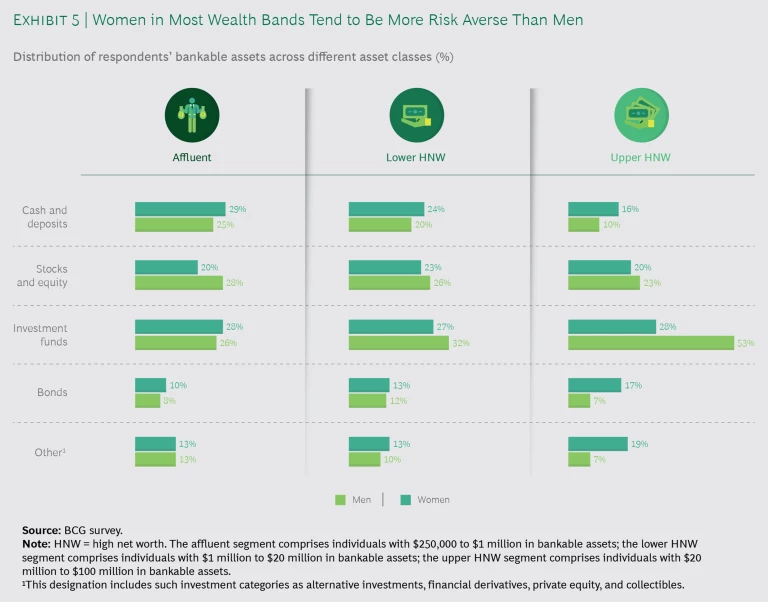

Because women tend to avoid uncertainty risk and require more data before taking the plunge into investing, they are also more likely to keep a higher percentage of their assets liquid. Although both men and women place the largest percentage of their wealth holdings into investment funds, men are more likely to choose publicly traded equities next, whereas women overwhelmingly prefer cash and deposits. (See Exhibit 5.) That preference for cash means that women risk losing out on higher-yield opportunities. With nearly 30% of their holdings concentrated in slower-growing assets, women can experience a wealth deficit during their retirement years—a deficit exacerbated by their having a longer average lifespan than men.

No More Back Seat: Millennial Women Are Taking Charge of Their Wealth

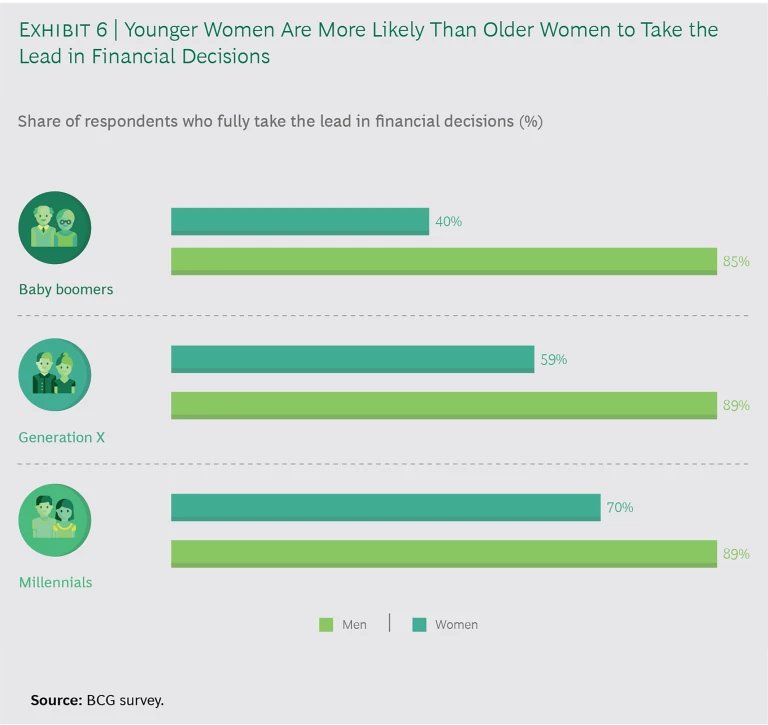

Younger women are more financially literate than older women, our survey shows, and that literacy translates into greater confidence and empowerment. An impressive 70% of millennial women (those born between 1980 and 1995) said that they take the lead in all financial decisions, compared with just 40% of female baby boomers. (See Exhibit 6.) That independence endures even as millennials marry. Unlike most women of past generations, 66% of married millennial women remain involved in financial decisions; the corresponding figure for female baby boomers is 29%. In all, our research found that gender-based differences in investor behavior and attitudes diminish as generations get younger, with millennial men and women sharing similar views, including a shared preference for purpose-driven investing in ESG and related topics.

The confidence that millennial women display is partly an outgrowth of their higher rates of educational attainment. Our study found that 91% of affluent and high-net-worth millennial women had obtained a university-level education, compared with 80% of female baby boomers. Other studies corroborate this shift. In the US, millennial women are the most highly educated generation to date. Almost half (46%) of employed millennial women from 25 to 29 had a bachelor’s degree or more; that compares to 36% of Gen X women who were in the same age tier in 2000.

Moreover, younger women are entering the workforce in greater numbers. Of the female millennials who participated in our study, 98% are in professional careers, compared with 86% of female Gen-Yers and 73% of female baby boomers. They also embrace entrepreneurship and self-employment and, in many cases, are gaining greater earning power and flexibility. As a result, young women today are earning a greater share of their own wealth than young women of prior generations did. With that can come a stronger sense of empowerment and agency.

Of the millennial women who participated in our study, 98% are in professional careers, compared with 86% of female Gen-Yers and 73% of female baby boomers.

Cultural Differences Play a Significant Role in Shaping Investment Behavior

Attitudes about women and wealth vary across regions. Women in the Middle East, for example, face cultural barriers that limit their role in financial affairs. In our survey, no Middle Eastern women respondents said that they were involved in making financial decisions.

The opposite is true in Asia where most female respondents in our survey stated that they take the lead in managing financial decisions for their households. This was true regardless of whether women earned the money themselves or inherited it. Ling Xia, head of private banking at the Bank of Shanghai, said, “In China, the wealth market is still young. In general, men in the family still put more focus on creating new wealth, while women are responsible for managing the accumulated wealth and putting it in the bank where they expect to earn a more stable return. As a result, women make up a larger proportion of our customers.”

The story is similar in North America, where women say that they make the majority of wealth management decisions, regardless of the origin of that wealth. Across the Atlantic, European men and women seem to share financial and investment planning responsibility jointly.

Unconscious Bias Still Permeates the Wealth Management Sector

Even though financial institutions and wealth managers have been paying more attention to the women’s wealth segment in recent years, their approach shows signs of being mired in the past. Too often, firms treat women as a homogeneous group, ignoring the vastly different needs and preferences of different female clients. In addition, banks commonly view the women’s segment through a marketing lens and not from a business revenue and growth perspective. Most problematic are attitudes that reflect prevailing stereotypes. In interviews, many women told us that they feel “talked down to” in wealth management discussions and that advisors frequently assume that a woman’s wealth comes from her spouse or family. In our survey, 30% of the women participating said that their relationship manager spoke to them differently because of their gender. One wealth management client told us that a few days after she and her husband had their first meeting with a new advisor, the advisor sent the couple a package that included follow-up documents for her husband and a bracelet for her, even though the woman was the primary breadwinner in the relationship. Another woman told us that after her husband died, her wealth manager assumed that she would not want to be engaged in financial decisions. She promptly switched wealth managers.

Such tone-deafness is alienating: 64% of female respondents felt that their bank or wealth management provider needs to improve its value proposition, with working women and those in the highest wealth bands expressing their discontent with current models most acutely. Advisors should take note. Although wealth management relationships tend to be stickier and longer lasting than other banking partnerships, our research finds women are more likely than men to switch managers.

Firms that pay attention to women’s specific needs and preferences and tailor their service accordingly can capture a large share of this important and growing market.

Firms that pay attention to women’s specific needs and preferences and tailor their service accordingly can capture a large share of this important and growing market.

To Win the ’20s, Wealth Managers Must Focus on the Individual, Not the Gender

With women’s wealth expected to reach $93 trillion globally by 2023, we believe the ’20s will be a watershed decade for women and wealth.

Wealth advisors have been late to apprehend this shift, but they can turn things around. The most successful will take committed steps such as the following.

Create a culture of conscious inclusion. Wealth managers must address the industry’s deep-seated biases. Outdated assumptions about what female investors want, combined with an inadequate understanding of women’s actual behaviors and preferences, have contributed to subpar service. Female clients frequently complain of subtle—and sometimes not-so-subtle—slights; for example, advisors may direct comments to the husband or male partner and dumb down the information they provide to women. Unless banks and firms address this underlying bias, they will lose the women’s market, regardless of how stellar their products or how advanced their analytics may be. Sofia Merlo of BNP Paribas said, “It’s all about inclusion. Five years from now we should be talking parity. This for me is the new normal.”

To root out prejudicial assumptions, wealth managers must create a more consciously inclusive workplace and service environment. That starts with a recognition that everyone has biases. As our brains absorb and synthesize vast amounts of data, they take shortcuts, slotting information into categories and applying attributions—for example, assuming that dogs that bare their teeth are not friendly. These neural processing shortcuts can help us make time-sensitive decisions—for example, avoid that dog. But they can also introduce false connections—for example, the notion that men are the hunter gatherers and thus the primary income earners in society, or the idea that women are empathetic and therefore prefer soft topics. Because most neural activity takes place subconsciously, we may not be aware of the implicit biases we form.

Senior leaders and relationship managers alike need to learn what their unconscious biases are and become attuned to how those biases may be affecting the institution’s tone and the service it offers, so they can make positive changes to culture and behavior. The implicit association test (IAT), developed by Harvard University, is now a widely used tool in other industries. The test can reveal underlying attitudes and beliefs that individuals may not have known they hold. As part of a wider inclusion initiative, the IAT can help banks gain more systematic insight into personal judgments so they can see where interventions are most needed.

Wealth managers should also update training regimes to mitigate biases and increase cultural competency. Diversity education must do more than simply lay out the firm’s values, and it must extend beyond gender topics. Women represent 50% of the world’s population. Continuing to bundle this large and varied group into one generic diversity box is outdated and reductive. Effective training should detail specific practices and the verbal and nonverbal behaviors that undermine inclusion. Field and forum sessions that enable employees and managers to practice what they’ve learned and then meet with mentors or their training group to share feedback and refine their client communications can help embed the knowledge, resulting in more targeted, relevant, and actionable training.

These are just the basics. To truly differentiate themselves, wealth managers need to shift their culture to become inclusive and client focused. One of the most tangible and effective ways to do this is by creating varied teams. BCG How Diverse Leadership Teams Boost Innovation that the EBIT margins of organizations with diverse management teams are 9 percentage points higher than those of organizations with below-average diversity. The research shows not only that female advisors perform as well as or better than their male peers, but also that clients with female relationship managers are more likely to feel that their bank is a trusted advisor that acts in their best interests. (See “Women’s Wealth Is Growing—Why Not the Number of Women Wealth Advisors?”)

To truly differentiate themselves, wealth managers need to shift their culture to become inclusive and client focused.

Women’s Wealth Is Growing—Why Not the Number of Women Wealth Advisors?

Women’s Wealth Is Growing—Why Not the Number of Women Wealth Advisors?

Although women represent almost half of the financial services workforce in many countries, they remain underrepresented in segments such as investment banking and personal wealth. Among the wealth management clients we surveyed, only 39% of women had female relationship managers, and only 23% of men did. The imbalance represents a missed opportunity—not because women prefer female advisors (our survey found women to be more or less equally satisfied with advisors of either gender), but because female advisors may be more effective at representing the bank and managing client relationships with both male and female clients. For example, women with female relationship managers were 1.7 times more likely than other women to “strongly agree” that their bank acts in their best interests.* Men with female advisors strongly agreed with that proposition at an even higher rate than other men (1.8 times).

Why does the number of female wealth advisors remain low in many advanced markets? A BCG study that included 2,500 financial services employees found that, although women in financial services are more likely to feel that their institution is committed to diversity than women in other industries, only a third of women working in financial services believe that they have benefited from those programs. The study found that women in financial services perceived greater obstacles to gender diversity than women in other industries did. This pattern held true across the employee life cycle, from recruiting to retention. Women in financial services were also 20% more likely to report challenges to advancement than women in other sectors.

One of the study’s key findings is that most decision makers in financial services institutions (overwhelmingly white heterosexual men aged 45 or older) underestimate the obstacles that women face. This lack of understanding leads many institutions to prioritize some initiatives that are less important to women over efforts in other areas that women say would benefit them more. Banks and wealth management firms need to make a firm commitment to address the right set of issues meaningfully. Creating an inclusive environment that unlocks the potential of their female workforce will close the gender gap, improve client satisfaction, and enhance the firm’s reputation overall.

NOTE

* Source: BCG survey, Women@BCG, 2020.

Another way to reduce bias is to use standardized questions during the onboarding process. For instance, advisors at this stage tend to ask female clients less often than male clients about their personal and financial information. Incomplete information can lead to faulty assumptions and ill-fitting recommendations, which in turn can make women feel misheard or undervalued. By collecting the same types of information from both men and women, wealth managers can establish an objective baseline to help them make recommendations on the basis of the whole individual, not merely on the basis of gender. Banks and others then need to build on these basics to create a culture and an environment that are truly and consciously inclusive. They should also adapt performance management and incentive structures to encourage transparency in decision-making processes, and embed and reward desired behaviors.

Helping women catalog their wealth management priorities and then designing a portfolio aligned with those priorities can profoundly change the service paradigm.

Focus on the individual. Women do not want or need products that are different from those offered to men. Rather, they want a personalized approach that is tailored to their financial objectives and personal goals. As Beatriz Sanchez, regional head of Latin America and member of the executive board at Julius Baer & Co. Ltd., said, “It is about treating the individual. Banks need to treat female clients the same way they treat men but must realize the dialogue needs to be different.” Advisors need to shift that dialogue to focus on goals and to understand specific outcomes that female clients want to achieve, as well as the desires behind them. For example, two women might wish to retire from their current jobs at age 55, but one might be interested in having enough funds to travel the world, while the other might be interested in starting a new venture. Achieving these goals calls for satisfying very different investment requirements. Helping women catalog their wealth management priorities and then designing a portfolio that is aligned with those priorities can change the service paradigm in profound ways, enriching the quality of client conversations and improving outcomes.

Banks that distinguish their service most successfully will take personalization even further, helping female clients model the impact of different priorities—such as generational planning, philanthropic giving, or sponsoring a family entrepreneur—and offering specific guidance on how women can plan for these events while continuing to advance their overarching wealth goals. Northern Trust’s Steph Wagner adds, “These approaches must respond to the fact that women are living longer, living single before and after marriage longer, and seeking more alternative investments, and must factor these generational changes into wealth goals and investment patterns.”

Recognizing the importance of data, leading advisors will use visualizations, simulations, and analytics to help women reach informed decisions. Dynamic tools that make it easy to evaluate different scenarios can enable women to see how they might put a portion of their cash and deposits to more productive use while preserving the liquidity they need.

The same ethos should apply to marketing and communications. Some women who are new to investing might enjoy female-only events, seeing them as a safe environment where they can ask questions they might otherwise be uncomfortable posing; but more experienced investors and women in the upper wealth bands might get more value from inclusive events that offer access to a range of ideas and insights. As Anke Sahlen, market head for North Germany for Deutsche Bank Wealth Management, observed, “Banks need to listen and understand what types of events and topics women are interested in and cater to that.”

Unlike the product-led wealth management model of the past, the new wealth management model will focus on the whole person, not on their gender. By examining preconceptions about female investors, moving beyond labels to treat the individual, and shifting to a goal-based and evidence-backed advisory approach, banks and others can win share in this important and rapidly expanding market. Beatriz Sanchez put it well: “Women will increasingly become more demanding and seek more information to make their own decisions, instead of delegating them to someone else. They will continue to be an economic force to the point where, hopefully, in five years, we will no longer be asking if women should be treated differently.”