More than 2 billion people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) lack access to crucial medicines. Over the next four decades, serious health-related suffering is expected to rise three times faster in low-income countries than high-income countries.

The So What

Although biopharma companies are strategizing new ways to enhance access to medicines, some 70% of R&D priorities for LMICs, including maternal conditions and infectious diseases, remain unaddressed. (See the exhibit.) Currently, drugs are six times more likely to be registered for regulatory approval in upper-middle-income countries than in LMICs.

But LMICs represent a large, untapped market for biopharma companies seeking growth opportunities. For example, the global insulin market is worth approximately $25 billion to $35 billion per year, yet approximately half of patients who need it cannot obtain it. If companies could serve just 10% of this population at less than one-third of the average price, insulin manufacturers would yield an additional $1 billion.

By leveraging innovative business models and partnerships with the right players, companies could reach these markets at no extra cost, delivering a win-win for biopharma and patients in need. So what are the barriers to people in LMICs receiving these vital medicines?

The Backdrop

Four barriers stand in the way, as seen in the slideshow:

Barriers to Adaptation. Typically, medical products are not designed and developed with the needs of the LMIC patients or the constraints of their health systems in mind. For example, certain drugs may require diagnostics to be performed by a specialized doctor—a scarce resource in LMICs. If products were designed in such a way that health care workers could perform the diagnostics, many more patients could gain access to the drug. This worked well for HIV when the strategy moved to a universal “test and treat” approach (testing and immediately treating HIV positive individuals regardless of stage of infection) in combination with a standardized drug regimen (using predefined treatments versus customized ones).

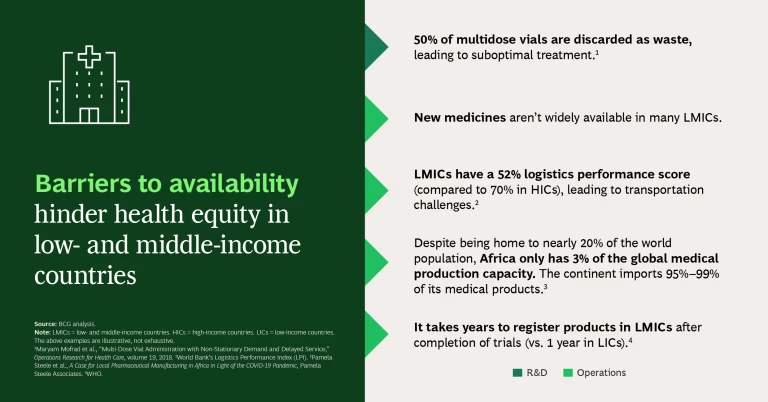

Barriers to Availability. Drugs may not be available (or not sufficiently available) in LMICs because they lack regulatory approval, there are limited numbers of manufacturers, or production capacity is constrained.

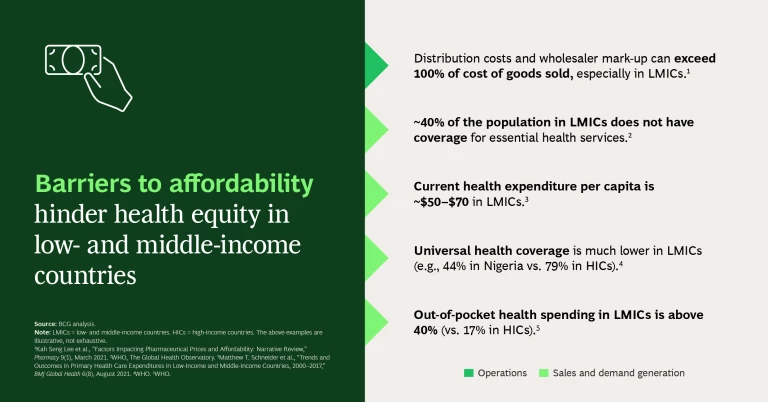

Barriers to Affordability. Patients or health systems cannot afford the costs associated with the medicines.

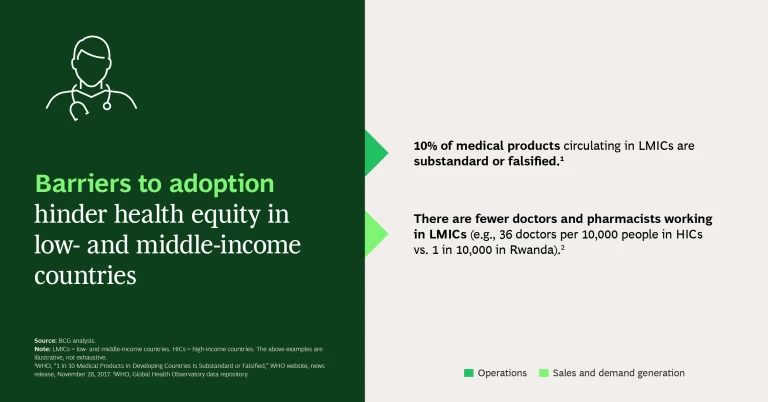

Barriers to Adoption. Adoption can be hindered because of health care worker shortages, national treatment guidelines that don’t include the drug, or limited awareness of the product’s availability. While high-income countries may also face barriers to adoption (as with vaccine hesitancy, for example), the health systems have very effective mechanisms to communicate with and educate patients whereas LMICs need to communicate through communities.

What works in high-income countries doesn’t usually work in the same way in LMICs because they have so many fundamental differences, so strategies need to be adapted accordingly.

The Idea in Action

When stakeholders work together to overcome these barriers, they save lives. With HIV, for example, the global community, public sector, private sector, governments, and civil society, among others, came together to:

- Adapt the pill regimen.

- Increase the availability of HIV drugs by diversifying the pool of suppliers, sharing regular demand forecasts with manufacturers, and signing long-term agreements with suppliers.

- Lower prices with voluntary licensing agreements and pooled procurement.

- Promote adoption through awareness campaigns.

For malaria, the global community, public sector, private sector, governments, civil society, and other stakeholders worked together to:

- Develop dispersible antimalarials, which are much easier to administer to children under five years old (who represent 80% of malaria cases).

- Increase availability by diversifying the pool of suppliers.

- Increase affordability through pooled procurement and long-term agreements with generic makers.

- Educate physicians and pharmacies about the importance of shifting away from lower-quality antimalarials and monotherapies to embrace high-quality artemisinin-based combination therapies.

Now What

Biopharma leaders can take four actions to seize the opportunity within health equity:

- Segment the markets. Segment markets not only by geography but also by the maturity of health systems. Even neighboring LMICs will have widely different needs, infrastructure, and capabilities. Segmentation will help calibrate the level and type of effort needed to be successful in a given market and identify markets where a proven approach can be used with minimal adaptation.

- Share opportunities. If you won’t be entering a particular market for several years, consider licensing products to generic players in that market. With adequate risk management, you can help millions of people gain access to a drug at no cost to you.

- Identify efficiencies. Seek out common requirements that are uniform across multiple geographies, such as harmonized international regulatory standards, to reduce the time and cost associated with entering new markets. In addition, find regional partners with expertise in specific domains, such as supply chain, distribution, and marketing, to support unified efforts across multiple markets that are adapted to LMIC needs.

- Follow through. To create impact in LMICs, you need to build momentum at every step of the process. Just because a drug is offered at a low price, that doesn’t guarantee adoption. You also need to train health care workers, build patient awareness, overcome logistical hurdles, evaluate impact, and so forth. As in a relay race, you need strong performances at every position from beginning to end.

The authors would like to thank Ben Desmond, Akos Szabo, Guervan Adnet, and Robin Lavers for their contributions to this article.