For multinational pharmaceutical companies, Indonesia is simply impossible to ignore. An emerging Southeast Asian market with nearly 240 million people and a fast-growing middle class, the archipelago nation boasts strong macroeconomic fundamentals despite short-term headwinds caused by shifts in the global economy, a high current-account deficit, and relatively aggressive inflation. Economic growth is projected to continue at roughly 6 percent into the medium term. And because of an expanding middle class, domestic consumption will likely account for about 55 percent of growth.

The fundamentals of Indonesia’s health-care market also make the country attractive to multinational pharma players. The public has a strong interest in better health care: Indonesia’s health-care spending more than doubled from 2006 through 2011. Spending on prescription pharmaceuticals, at roughly $4 billion a year, is the highest in the ASEAN region and is growing at more than 10 percent annually. Per capita spending on pharmaceuticals, however, is low relative to that of other Southeast Asian countries, leaving ample headroom for growth as personal incomes and health care spending rise. And with a shifting disease burden that increasingly resembles that of the developed world (oncology, for example, is the country’s fastest-growing therapeutic area), demand from Indonesian patients and physicians for higher-quality care and more sophisticated therapies is all but certain to mount over time.

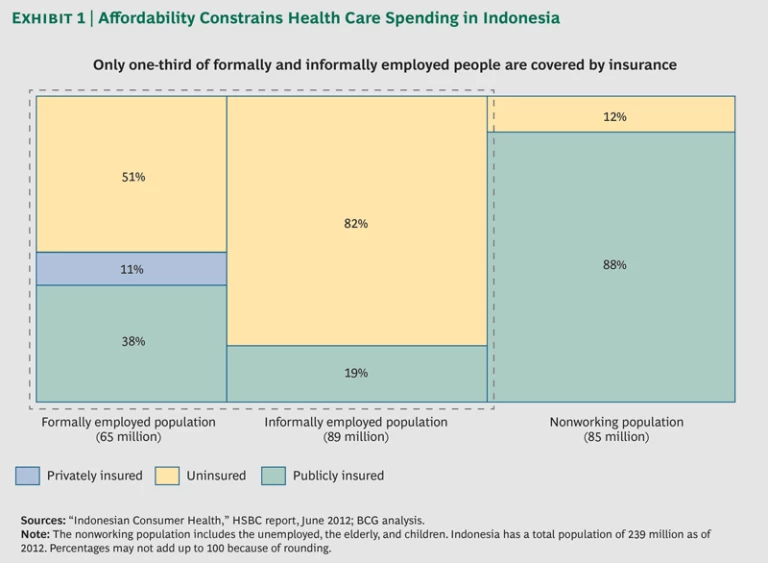

The latest development to catch industry leaders’ attention is the government’s planned rollout of an ambitious national health-insurance scheme that aims to cover 100 percent of the population. Under the current system, roughly 50 percent of the population is covered by one of six government insurance programs. These range from relatively small subsidies for the poor and unemployed, with large gaps in coverage, to a variety of more comprehensive policies for civil servants, the police, and the military. The results of the 2014 presidential election, however, could significantly alter both the timing of the national rollout and the level of coverage available to the general population. And as the current 2019 target for full rollout draws ever closer, policymakers are still debating key details of the insurance system and its enabling mechanisms. At this stage, it is impossible to predict what model will eventually emerge as the national template and when such a model will be realized.

In this climate of uncertainty, it appears that multinational companies have few short-term growth opportunities in the public health-care market. By contrast, the private market has far more immediate appeal. And because of favorable demographic trends and income growth, the private market offers longer-term benefits as well. To capitalize on both the long- and shorter-term opportunities, multinationals will need to develop local savvy, cultivate new stakeholders, and attract scarce talent. In short, to participate successfully in Indonesia’s fast-developing health-care sector, big pharma will have to pick targets carefully and develop a detailed operating model tailored to local conditions.

Two Funding Streams, Two Distinct Markets

Two major funding streams underpin Indonesia’s pharmaceuticals market. Six different public-insurance programs cover about 50 percent of the population and provide differing benefit levels. The other half of the population pays mostly out of pocket for medication and treatment, and affordability remains a major constraint on health care spending. (See Exhibit 1.) The health care infrastructure is underdeveloped, with a ratio of 6.3 beds per 10,000 citizens, well below the global average of 30 per 10,000. Yet hospitals run at an average of 55 to 60 percent of capacity, owing largely to issues of affordability, low confidence in the health care system, and a chronic shortage of physicians that exists, in part, because of government policies that bar most foreign doctors from practicing in Indonesia. As a result, lower-income Indonesians rely primarily on over-the-counter medications and traditional remedies, while more affluent Indonesians often travel abroad for medical care.

For the foreseeable future, the publicly funded segment of the pharmaceuticals market offers few profitable opportunities for the majority of multinational pharma companies that intend to retain their current product portfolios and operating models. The government has compiled FORNAS, a national formulary that focuses on lower-cost generics, as well as an “e-catalog” pricing mechanism meant to drive lowest-cost sourcing. Government policies that currently favor local generics producers, which control some 70 percent of the market, will likely continue. Most multinationals would need to change their operating models significantly to compete successfully against local generics players.

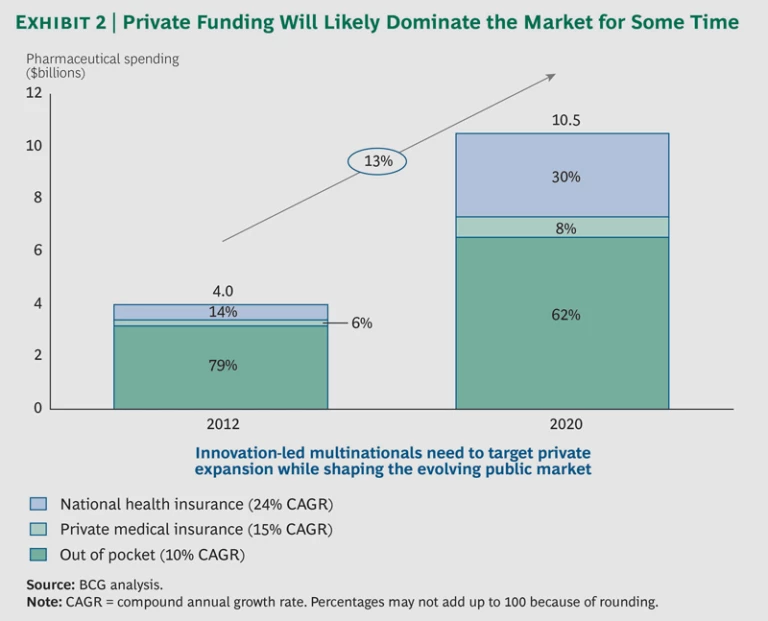

BCG’s analysis shows that in the current unsettled environment, the private market represents the more attractive opportunity for most multinational pharma companies. Because patients and private payers account for such a large share of overall health-care spending, it makes sense to invest now to better serve their evolving needs. Because of demographic and income-growth projections through 2020, the private sector will likely remain the best bet for multinationals in the medium and long term as well.

By contrast, the public sector provides little rational incentive to invest heavily in anticipation of the rollout of national health insurance. Multinationals should, rather, view national health care as a significant long-term opportunity and make targeted investments with that prospect in mind. In other words, companies need to enter the public market tactically and experimentally, gaining market intelligence with pilot ventures in some provinces and regions. Far more important than first-mover advantage in the public market is “signal advantage”—BCG’s term for the ability to sense and shape changes in the market.

At present, many multinational pharma companies lack the wherewithal to establish signal advantage. As outsiders, they have difficulty navigating the country’s policy apparatus, and without that capability, they have little means to formulate or implement strategies to help shape the national health-insurance scheme. Compounding the difficulty, the ministry of health is in the midst of a restructuring that will shift responsibility for many aspects of policy. For these reasons, we believe that before navigating the hazards of the public market, multinationals should get to know the overall Indonesian market intimately and hone their abilities to shape the direction of health care policy and the health care infrastructure over the longer term.

Finding the Sweet Spot in the Private Market

The private-market sector, supported by consumers and private insurers, is likely to be the most fertile ground for multinationals for some time to come. (See Exhibit 2.) Out-of-pocket expenditures currently dwarf public expenditures on drug therapies. In addition, the rapidly expanding middle class wants high-quality health care and is quickly acquiring the means to pay for it.

All the same, Indonesia’s private health-care market is very much that of a still-developing economic power. An estimated 70 million Indonesians will join the middle-class and affluent consumer population between 2014 and 2020. These households will have discretionary spending budgets of $220 or more per month (in 2013 dollars), and they have already demonstrated a willingness to trade up to improve family health. Private providers have begun targeting these consumers with care offers for different income levels. Yet because consumer incomes will remain low relative to those of developed economies, affordability issues will continue to constrain health care spending. Most members of the emerging middle class will have particular difficulty with out-of-pocket costs for specialist care such as newer cancer treatments.

Multinational pharma companies will need to tailor their offerings to the market, paying particular attention to meeting patient needs affordably. Some companies may consider collaborating with local health-care providers, private payers, and manufacturers to improve affordability and access to care, although multinationals will need expert advice to manage the risks inherent in complying with the rules of an evolving health-care system.

Physicians will play a vital role in communicating to patients the benefits of trading up from standard generic offerings. More-affluent Indonesians are willing to pay up for health care, but pharma leaders will need to make a convincing case that their products offer significantly higher quality at a competitive price. Because physicians are crucial to this effort and offer the best immediate point of entry to the Indonesian market, multinationals need to develop strong relationships with private health-care providers. Pharma leaders will also need to build new skills in their field forces to demonstrate the value of their products to physicians.

By cultivating close relationships with private provider organizations and payers, multinationals have an opportunity to shape drug formularies and score early wins that will lay the foundation for near- to medium-term growth. As the power of private providers increases in a changing competitive landscape, however, these companies will need to manage their key-account relationships to balance conversations about pricing with conversations about the value that companies can offer providers. By helping with physician training, sharing information, collaborating on common challenges, and bundling products and solutions, multinationals can emphasize their commitment to serving providers’ needs and improving health care.

Pharma leaders should be aware, however, that a chronic shortage of doctors could hinder the growth of private hospitals. Current regulations bar virtually all foreign physicians from practicing in Indonesia, leaving many private providers undestaffed and underskilled and spurring more affluent Indonesians to seek care overseas. Private providers and multinationals share an interest in improving the quality and accessibility of local health care, and they should therefore be natural allies in the effort to improve the quantity and quality of the country’s health practitioners.

Finally, multinationals need to bear in mind that the local generics competitor base is already aggressively moving up the value chain into both the provision and pharmacy channels, which are rapidly professionalizing. Generics companies are expanding proprietary provider footprints, cooperating with other providers, and expanding their presence in retail pharmacies. These maneuvers compound the challenge and complexity that multinationals will encounter in the Indonesian market and carry clear implications for those companies’ strategic responses.

How to Think About the Indonesian Opportunity

Indonesia represents a critical emerging-market opportunity for multinational pharma companies. At the same time, it bristles with strategic and operational challenges that will likely narrow the range of short- to medium-term targets. Nonetheless, it’s important that multinationals move quickly to establish a presence in the country in order to gain in-depth local knowledge and launch efforts to attract in-demand high-level talent.

The public and private funding streams represent two distinct opportunities, each with its own time frame and magnitude. The private market is most relevant for multinationals because it offers the opportunity to demonstrate the effectiveness and affordability of product lineups and cultivate brand awareness in the short to medium term, and very likely the longer term as well. The public market is evolving, and its final shape is as unclear as the ultimate timetable for its implementation. It is therefore imperative that multinationals determine where to focus their investment and energy and fully align their strategy and operating models behind their chosen targets.

We believe multinationals should follow several critical precepts to define their approach to this complex and fast-changing market. These precepts call for pharma companies to do the following:

- Ensure clarity of focus. Clearly identify the company’s focus areas across the private and public sectors—and articulate the supporting rationale. Understand the factors for success in each market.

- Educate. Raise awareness of relevant disease areas among patients and physicians and improve understanding of therapies and variations in therapeutic quality.

- Tailor the portfolio. Ensure that the product portfolio is appropriate for the targeted customer segments. Experiment with tiered pricing, second brands, and other means to improve access and affordability.

- Establish and cultivate key relationships. As the market evolves, the cast of critical stakeholders for access and procurement will undergo continuous changes. Focus on identifying and understanding the agendas of critical patient populations, providers, physicians, payers, and policymakers. In the case of providers, for example, multinationals should identify the chains that represent the most compelling and relevant opportunities and work with them to define common interests and craft effective value propositions. Map the main decision makers and influencers within each key account and define a clear program as well as initiatives to engage them. Tailor value propositions to manage chain bargaining power and counter the local competition.

- Build signal advantage. In an uncertain and potentially malleable environment, companies must have strong capabilities in regulatory affairs and market access. Invest in them accordingly.

- Focus on commercial excellence. Use analytics to build on market data, limited though the data may be. Focus on segmentation and targeting, territory planning, and call quality as clear differentiators. One way to do this would be to identify relevant growth territories early, assess their potential evolution, and invest to build relevant local presence.

- Consider localization. Assess how local and regional economic trends might evolve before stepping up commitment. Likewise, an understanding of the requirements for local manufacturing and informed judgment on their potential evolution is an essential prerequisite for gauging the upsides of local production.

- Leverage partnerships. To increase access and market share, carefully assess the potential for mutually beneficial partnerships with both government and local stakeholders.

- Define a talent strategy. Develop a clear plan to secure key leadership and managerial talent, blending local and global experience. Build a sustainable approach to address a tight talent pipeline and mitigate staff turnover at all levels.

Indonesia’s rapid growth and the accelerating development of its health-care sector make it a tempting target for multinational pharmaceutical companies. But it is crucial to understand that Indonesia is not a single target, and the opportunities for multinationals are unevenly distributed across the health care landscape. Above all, multinationals must be aware that success will not arrive overnight. A health care market as multifaceted, complex, and rapidly evolving as Indonesia’s takes time to learn, and multinationals must develop the internal capabilities, product pipelines, and management talent they need to succeed there. Fortune will favor the patient, the well informed, and the well prepared.