Calls for racial and social justice—including pressure on workplaces to become more diverse, equitable, and inclusive—were amplified in 2020. Many US companies built upon their diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives and began new ones. But a significant portion of US employees we surveyed (22%), particularly racially and ethnically underrepresented employees (up to 34%), say that companies haven’t done enough.

This response tells us that despite companies’ efforts to combat racial and ethnic inequities by publicly condemning those inequities, pledging to increase the diversity of their workforce, hosting trainings and discussions among employees, and more, employees are not feeling the full intended effects. Some of this dissatisfaction may be explained by the time it can take for interventions to have a measurable impact. Still, our survey findings should prompt leaders to evaluate whether their current approach to DEI is setting them up for meaningful progress.

Creating an equitable and inclusive environment goes beyond just hiring a diverse team. Employees from underrepresented backgrounds also need support and opportunities as part of a comprehensive plan designed to span their careers.

We know that diversity has to be accompanied by inclusion if companies are to create a workforce and a culture that benefit from varied inputs and experiences. Inclusion is also closely related to an organization’s structural equity: if the processes and systems that support the day-to-day experience within organizations do not offer equal advantage to underrepresented employees, those employees may struggle to fit in or be their authentic selves at work. In short, inclusivity without equity doesn’t work. And a lack of workplace equity deprives an organization of the full potential and contributions of its racially and ethnically underrepresented talent.

Companies need an approach that positions DEI not as a do-gooder move but as a value-driving must.

Companies need a systemic approach that creates real change within their organization, one that pushes each employee to understand that achieving inclusivity and equity builds value for companies and opportunities throughout the workforce. Companies need an approach that positions DEI not as a do-gooder move but as a value-driving must.

What We Found About Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Workplace

Our survey measured employees’ perceptions of the obstacles they face at work as well as their personal experiences on the job. We found that perceptions vary according to race. White employees feel a greater sense of inclusion and equity within their company than do members of underrepresented groups. For instance, while 72% of white respondents agreed with the statement “My company’s values are inclusive and respectful of my identity,” the proportion was lower among underrepresented groups: 68% among Asian respondents , 67% among Latinx respondents, and 60% among Black respondents. (See the sidebar “Methodology.”)

Methodology

In this article we report race- and ethnicity-based findings from the 4,269 respondents in the United States.

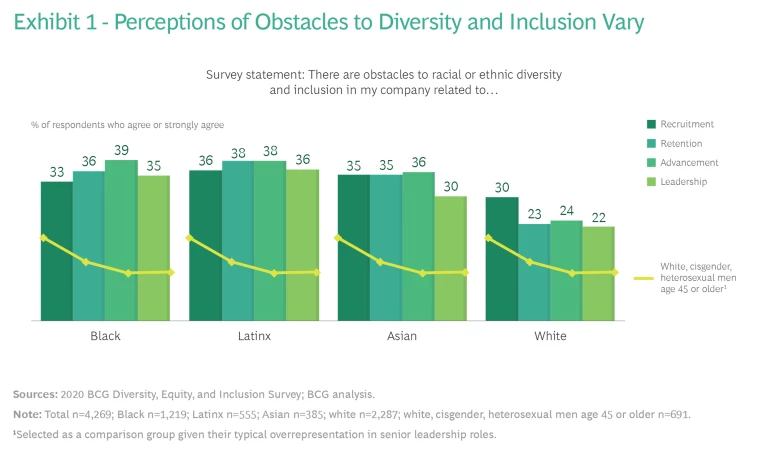

It is clear that racially and ethnically underrepresented groups have different perceptions of the workplace than their white colleagues. There is also a difference in their views of obstacles in the organization. We asked survey respondents whether they believe that diversity and inclusion challenges related to recruitment, retention, advancement, and leadership exist in their company. (See Exhibit 1.)

In each of those four dimensions, white employees were significantly less likely to agree that their organization has diversity and inclusion obstacles. Further, in all four areas, the gap between members of racially or ethnically underrepresented groups and white employees is magnified when we narrow the focus to white, cisgender, heterosexual men at least 45 years old—the demographic breakdown that is most likely to describe those in leadership roles. In practice, this means that leaders are not currently equipped with an awareness of obstacles or appropriate urgency about them and so aren’t positioned to take action to overcome them.

Leaders who aren't equipped with an awareness of obstacles or appropriate urgency about them aren’t positioned to take action to overcome them.

While perceptions vary across all four dimensions, the gap between white and underrepresented employees’ perceptions of obstacles is smallest for recruitment and most pronounced for retention and advancement. This aligns with BCG’s experience supporting a variety of clients on these topics. It also reflects one of the findings of our survey: that pledging to diversify the workforce is among the first commitments companies make related to racial equity. It should not be the last.

Recruiting is certainly important, but having a more diverse workforce is not the same as having an equitable and inclusive workplace, as other questions from our survey make clear. After being hired, members of racially underrepresented groups are more likely to experience disparities in the workplace related to episodes of discrimination and bias in day-to-day processes.

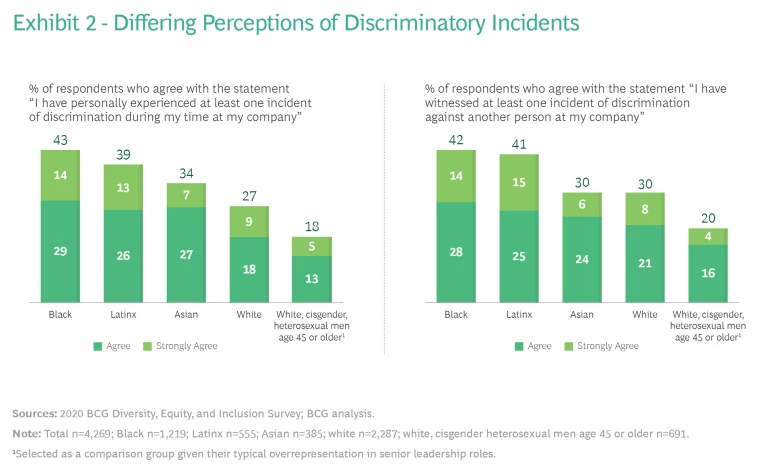

Specifically, relative to white employees, significantly more Black and Latinx employees surveyed report experiencing at least one incident of discrimination and witnessing at least one such incident while at their current company. (See Exhibit 2.)

To make matters worse, nearly 20% of Black, Latinx, and Asian employees disagree or strongly disagree that there are consequences at their company for those who behave disrespectfully or that they feel comfortable reporting discrimination without fear of retribution. Employees of color also report limited belief in their company’s resolution mechanisms relative to the responses provided by white employees.

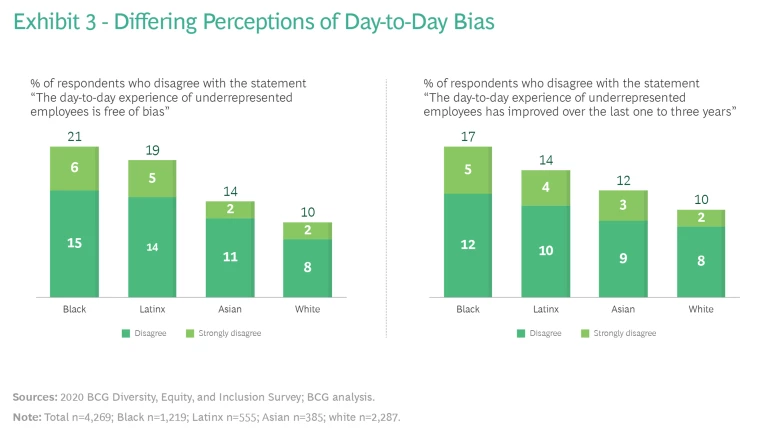

Fifty-six percent of white respondents report that their workplace is free of day-to-day bias. But a sizeable proportion of the racially or ethnically underrepresented groups (roughly twice as many Black and Latinx respondents as white respondents) disagreed or strongly disagreed. Perhaps of even greater concern, many employees do not feel that their companies have made progress on this front over the past one to three years. (See Exhibit 3.)

We advise that leaders consider the whole employee life cycle, from being hired to being supported, developed, and promoted.

What the Employee Life Cycle Looks Like for Racially and Ethnically Underrepresented Groups

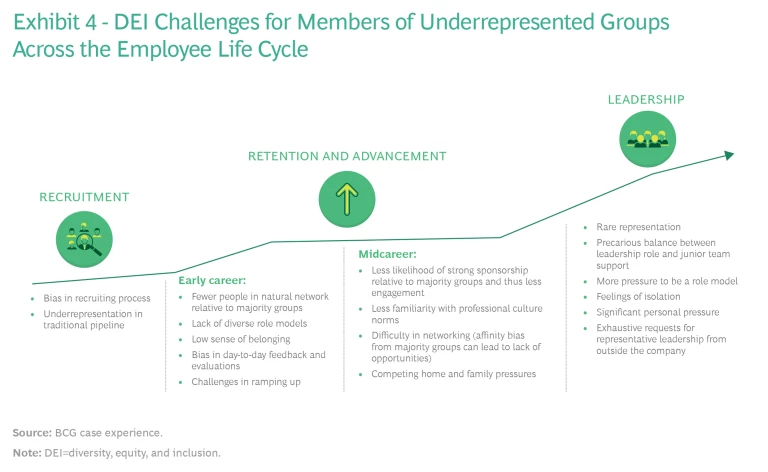

Employees in racially and ethnically underrepresented groups in our survey saw more obstacles related to retention and advancement than to recruitment. This finding suggests that leaders should ask themselves not only whether they have hired a diverse team but also whether they have created an equitable and inclusive environment for underrepresented groups.

Exhibit 4 shows a (non-exhaustive) view of the challenges we often see at various stages in the employee life cycle for racially or ethnically underrepresented groups.

The particular experiences and challenges that employees from underrepresented groups tend to face result in a lack of equitable retention, advancement, and promotion. That’s obviously detrimental to the careers and well-being of these individuals. It’s also bad for companies: they miss out on the rich variety of experiences and insights a diverse workforce can bring.

Consider the experience of a hypothetical company whose market research reveals that the biggest source of potential growth lies in marketing and selling its offering to racially diverse consumer groups. Then consider the challenge when it realizes how woefully underrepresented those groups are within the company itself, particularly within frontline management. In a scenario like that, the failure to retain and advance employees of diverse backgrounds leaves a company ill-equipped to tap into opportunities and vulnerable to better-prepared competitors.

What Companies Can Do Next to Address Racial and Ethnic Inequity

We applaud the efforts that companies are making, but our survey results show that those attempts are not having the desired outcomes in terms of employee sentiment. It might be that not enough time has elapsed for their efforts to take effect, or it might be that those efforts don’t go far enough, are not systemic in nature, or aren’t well matched to the actual needs within the organization.

We’ve worked with a variety of clients to design DEI approaches. To make lasting change, we recommend that companies pursue ongoing efforts in the following areas.

Know your organization. To move forward, it’s crucial to understand the specific experiences of employees of all racial and ethnic backgrounds within the organization. You might, for instance, find that even within a single racial group, particular patterns tied to factors such as country of origin, language or accent, or religious belief make the culture less inclusive and equitable. Particularly in a large or international organization, marginalization can manifest in complex ways.

Dedicate time and resources to understanding all potential issues in order to surface the unique challenges within your organization through multiple avenues, including carefully planned surveys, focus groups, employee resource groups, authentic conversations, and executive engagement initiatives.

It’s important to be deeply introspective throughout this process to reveal where the organization is doing well and where it is not. When examining areas where it’s not doing well, make sure you don’t simply accept common myths—like the idea that there is no pipeline of diverse employees—as the cause. Instead, challenge those anecdotes with facts to ensure that you are digging down to the true root causes of the shortcomings. Only then will you begin to uncover ways to fix them.

Set aspirations and measure progress. With the insights derived from building a thorough understanding of their organization, companies will be ready to set measurable aspirations for the future. For example, in reviewing their current organization, leaders may discover that racially or ethnically underrepresented groups are promoted at lower rates than are white employees. Such insights should spark action. Companies might reexamine management development programs, including how managers coach and evaluate diverse talent. They might increase mentorship and sponsorship accountability for junior employees from underrepresented groups. Those actions, once set, should be monitored and tied to accountability.

Aspirations should also be tied to realities. An organization can make a sincere pledge for change without understanding the resources and time required to make that goal a reality. For example, an organization’s examination of its workforce could reveal that a particular group is underrepresented, prompting a declaration to, say, double the representation of that group within three years. But what will that really require? Rates of hiring, attrition, and promotion, along with other factors, must be taken into account. Companies must understand the requirements and form a realistic view of when today’s efforts will yield results. Even for organizations that have a high rate of turnover and change, progress will take time.

The most difficult aspect of aspiration setting will also, ultimately, be the most valuable: knowing what “good” looks like. When has an organization become truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive? Tools and metrics can help. For instance, Management Leadership for Tomorrow’s Black Equity at Work Certification offers clear standards for employers regarding Black employee equity.

Maintain your commitment. Ensure that senior leaders are clear and vocal about the company’s values and commitments. Public statements alone are not sufficient to change an organization’s culture or to bring about greater DEI—though they are an essential step. Arm frontline leaders with the education and tools to reinforce that message in their everyday interactions.

These moves begin with the dedication and support of top leadership. Making the intent stick requires work norms and rituals to change, and organizations need to rely on their middle or frontline managers to do that. Equip them with the necessary tools and resources, such as training in ways of working that will help build inclusivity and equity.

Organizations should also help their middle and frontline leaders understand that diversity, equity, and inclusion are business priorities and drivers of business values. To be effective, DEI needs to become personally important to the segment of leadership that, without specific attention, can become a “frozen middle” in organizations. Helping middle management understand how DEI can advance their objectives can thaw support among this cohort.

Organizations should help their middle and frontline leaders understand that diversity, equity, and inclusion are business priorities.

Recalibrate your day-to-day processes to create new experiences. Achieving inclusivity requires cultural change, and achieving equity requires structural change. These transformations should begin with adjusting internal processes and systems. Look at performance management systems, which were built decades ago and based on the experience of white male employees. Also reconsider your organization’s approach to project assignments, advancement, conflict resolution, and more.

Additional moves: recognize a broader range of cultural holidays, plan affiliation events, and use inclusive language in company communications and nomenclature. In particular, middle and frontline managers should be educated on the importance of psychological safety and allowing employees to be heard and should be taught practical ways to pursue those objectives. For example, leaders can adopt practices like holding a daily standup meeting as a mechanism for hearing employee perspectives and offering support.

Amplify the best employee support practices. Many companies offer valuable support to their employees in the form of benefits, flexibility, structured career development, and more. There is room to build on those resources, recognizing that not every employee needs the same type of support. For example, a BCG study found that Black and Latinx employees were at higher risk of attrition from their jobs due to a lack of support regarding their caregiving responsibilities compared with Asian and white employees. In this instance, having robust flexibility options would support a non-obvious need among racially underrepresented employees.

With that in mind, potential actions can include providing easily accessible mentorship and development opportunities, maintaining robust wellness benefits and offerings that encompass both physical and mental health, and extending flexible work options such as remote work, flexible hours, and leave of absence.

Underlying the specific benefits or options offered is the basic yet vastly meaningful concept of support. The emphasis for the organization should be on finding ways to demonstrate and deliver clear, equitable, and inclusive care for all of its employees.

The perceptions our survey captured in 2020 can help guide organizations as they seek to further elevate their DEI efforts. It’s important to see these undertakings as a long-term initiative; these challenges existed well before 2020, and they will endure long after without concerted, ongoing, systemic change.

The increased dialogue and action we’ve seen over the past year are promising, but we can’t let them become passing trends. We should treat DEI as we do other wide-reaching and long-term challenges in our organizations: with a comprehensive and continuous plan for change. One-off or reactionary efforts will fail to address the root causes of inequities and negative employee experiences. Instead, organizations should find enduring ways to commit to DEI.

The authors thank Alexis Williams, Jay Lundy, and Susanne Locklair for their contributions to this article.