With the flattened hierarchies of today’s distributed corporate environment, the model of the heroic leader who single-handedly produces results through sheer force of will has become obsolete. Leadership at the top is now a team sport. CEOs rely on senior-level teams to accomplish important goals, manage change, and help spread the company’s priorities and values throughout the organization.

But in a volatile and uncertain business environment, executives are finding it harder than ever to keep up. Top teams therefore must be more than just high performing. They also need to adapt and thrive, regardless of the turbulence they face.

Adaptation conjures up images of animals that evolve reactively in a survival-of-the-fittest competition. However, top teams don’t simply react. They proactively cultivate the fitness to survive through a disciplined approach that anticipates and shapes the future.

Adapt and Thrive

While it may require significant effort to cultivate a high-performing and adaptive leadership team, the work delivers a strong payback. A BCG Strategy Institute study titled “The Value of Adaptive Advantage” shows that more-adaptive companies generate powerful economic and financial gains. These companies consistently outperform their industry peers during periods of volatility, and they sustain superior performance over time, whether it’s 5 years or 30 years. The results also show a strong correlation between a company’s adaptability index score and total shareholder return.

Senior leadership teams are the engines that power this kind of performance. In its new Adaptive Leadership Teams Survey, BCG complemented the Strategy Institute’s research by examining the link between a company’s performance versus its peers and the adaptive capacity of its senior-leadership team. We found a correlation between the two factors. Employees also enjoy a more emotionally rich and engaging company experience when they are part of adaptive teams.

BCG studied a carefully selected sample of companies to discern what the most adaptive leadership teams do differently or better than those teams that deliver average or substandard results. Digging deep into the specific characteristics of adaptation, we conducted both quantitative and qualitative assessments of nine intact leadership teams across a mix of industries, business sizes, regions, and company life cycles.

We interviewed more than 100 executive members of these teams, including CEOs, business unit leaders, and functional leaders of both genders and from a mix of international backgrounds. We studied nine companies in such industries as financial services, telecommunications, medical technology, chemicals, consumer goods, travel and hospitality, pharmaceuticals, and private equity.

The companies ranged in size from 300 to 130,000 employees and included both local and multinational companies in developed and developing markets.

Regardless of industry, size, location, and company life cycle, these companies with adaptive leadership teams all outperformed their peers—some just slightly and some by a significant margin. Through their business performance in a variety of environments, all have demonstrated that agility and adaptation are, to a greater or lesser extent, part of their company DNA.

The results disproved some common fallacies about teamwork and adaptiveness. For instance, observers often claim that as companies get bigger, they get less adaptive. We found that not to be true. Adaptability also often implies a lack of discipline. We found just the opposite: adaptive teams have highly disciplined mechanisms and processes that free them up to be more adaptive. Further, in today’s business context, adaptability can no longer be thought of as an ad hoc skill or last-gasp maneuver that is brought to bear only in times of desperation. In fact, when asked if there were conditions under which leadership teams should not cultivate adaptive capacity, the overwhelming majority of leaders struggled to find examples—especially given the current marketplace challenges faced by even the most stable business models.

The correlation between performance and adaptive capacity raises several questions:

- What makes an adaptive leadership team?

- What do adaptive team leaders do differently?

- How does adaptation become part of an organization’s DNA?

- How does a leadership team know if it is adaptive enough?

What Makes an Adaptive Leadership Team?

The study reaffirmed that the basics of effective teamwork still apply. Adaptive teams lay the groundwork by adhering to the following principles.

- Distributed Leadership. The team leader believes in the value of sharing leadership at the top and developing leaders at every level.

- Optimal Talent Mix. The team is not only composed of the top talent representing key positions and disciplines but also has the chemistry that comes from the right combination of backgrounds, styles, and perspectives.

- Clear Charter. The team has defined goals, roles, ground rules, and accountabilities.

- Mutual Trust. Team members are able to express divergent views and let down their guard to acknowledge when they need help.

Not every team studied was at the same level on the four basics, suggesting that even our select sample of leadership teams had room to improve in these fundamental team principles. Still, all the teams studied exhibited these key characteristics of high performance; displayed them at higher levels than other teams; and demonstrated a high correlation between principles of teamwork and their own assessments of team and company performance.

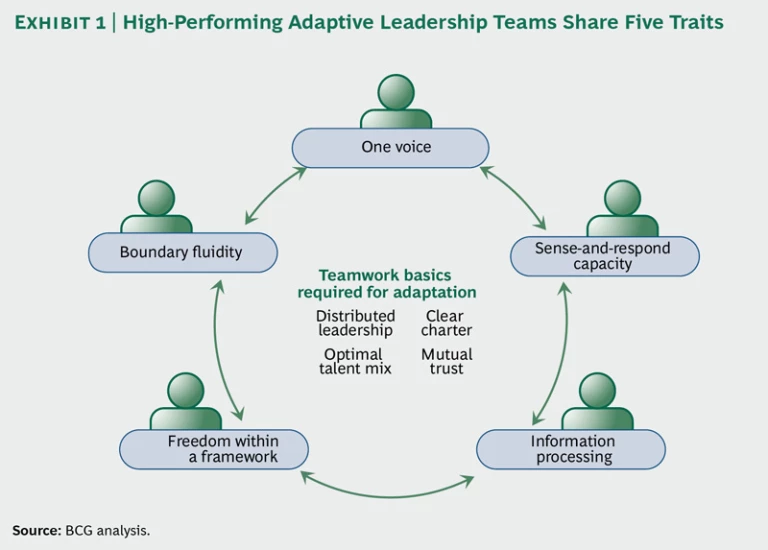

As important as these basics are, however, the study showed that high-performing, adaptive leadership teams have five added traits—the “special sauce,” so to speak—that set them apart from those teams that are merely adequate at what they do. (See Exhibit 1 below.)

One Voice. Adaptive teams take the time to get completely aligned about the organization’s vision, values, and vital priorities, while respecting individual differences of opinion and experience. Once a diverse team has reached agreement, members have the same “true north” guiding their strategic moves, and they display an absolute consistency in articulating that direction. Rather than demanding that employees follow a rules-based script that quickly grows out of date, leaders focus on transmitting the expected outcomes that can help steer the organization through any eventuality and allow experimentation to occur.

All the leadership teams addressed this characteristic in interviews. The top tier of teams distanced themselves most distinctively from the average score in the area of “one voice,” demonstrating how this attribute can separate moderately adaptive from highly adaptive teams. “If we don’t have alignment among the top ten leaders, we won’t be able to get alignment within the 100,000 employees,” said the CEO of a hospitality company. “It’s all about the type of culture that you create in the organization to create alignment around a strategy. This way you can feel comfortable delegating. There are too many people in too many different places, and our senior leadership team can’t do it all or know it all.”

Sense-and-Respond Capacity. Adaptive teams systematically use multiple real-time filters and amplifiers of information to monitor the external forces that drive change in their business environment. These filters often take the form of customized data mining, market research, dashboards, and war rooms. These enable the teams to excel at reading external signals, connecting disparate trends into meaningful patterns, and putting in place mechanisms that allow them to collectively separate the signal from the noise. When early-warning signs flash red, they are in a position to either consciously act differently or choose not to act—ahead of the curve.

All nine teams in the study provided examples of how they used their ability to sense and respond to build adaptive capacity. Sensing and responding was also one of the three characteristics that the 100 executives we interviewed mentioned most often. The highest scores in this area came from the leadership teams operating in global markets. “Adaptation is about knowing how the market is changing,” said an executive at a financial services company. “We are not reading about news after it’s occurred; instead, we are in the know before it is reported.”

Information Processing. Adaptive teams are able not just to sense when change is needed; they are also able to synthesize complex insights and make high-quality decisions quickly. They identify leading and lagging metrics that enable everyone to monitor progress in a way that is transparent and aligned with the company’s strategy and performance objectives. Several teams have developed highly disciplined meeting and agenda formats to ensure that they routinely exchange key information. In addition, adaptive teams are particularly good at processing information and making decisions at the junctures where different points of the matrix organization meet.

Seven out of the nine teams described excellence at information processing as a key characteristic of adaptive teams, and it was one of the top three characteristics mentioned by the team members we interviewed. “This isn’t about transmitting or receiving information but synthesizing the information,” said an executive at a medical-technology company. “When I use the word ‘synthesis,’ I’m describing people and teams that aren’t just a passive vessel but whose collective intelligences are the ingredients going into a soup. When you combine them together, all of a sudden you have the world’s greatest gumbo.”

Freedom Within a Framework. In addition to setting a common direction, adaptive leadership teams establish a framework within which the organization can experiment. Team leaders are empowered to take bold risks within agreed-to parameters, with failure seen as a possible and an acceptable outcome. Failure is only debilitating if the lessons learned are not disseminated and applied quickly. In this environment, employees earn greater autonomy to make decisions and investments as a reward for meeting objectives. “We set aggressive targets and give ‘blank checks’ to teams to move forward with their own plan, and the teams have responded positively and met all of their objectives,” concluded an executive of a food company.

Less than 50 percent of the companies interviewed focus on freedom within a framework as an adaptive capability. It may be a blind spot for leaders or a difficult trait to instill, since this principle had been effectively put into practice at only 33 percent of the companies we surveyed.

Boundary Fluidity. Adaptive teams can move both horizontally across roles and vertically to connect with the next level of leadership down from them. Team members can play out of position and pinch-hit for others at a moment’s notice, regardless of their role or how long they have been on the team. An operations person can oversee a human resources initiative, for instance. This role fluidity strengthens the bonds among team members. Also, team members do not see themselves as “masters of the universe” whose physical distance and behavioral norms somehow disconnect them from the organization. Senior-level leaders build a “neural network” of frequent conversations with the next level of managers down, exchanging more accurate information and establishing the trust necessary when a company needs to rapidly move in a new direction.

“The feeling that people have your back is a fabulous thing,” said an executive at an investment company. “This truly is a sense of comfort and confidence.” Only about half the leadership teams studied discussed boundary fluidity as an adaptive trait, however, showing that it takes practice to make this part of the leadership DNA.

What Do Adaptive Team Leaders Do Differently?

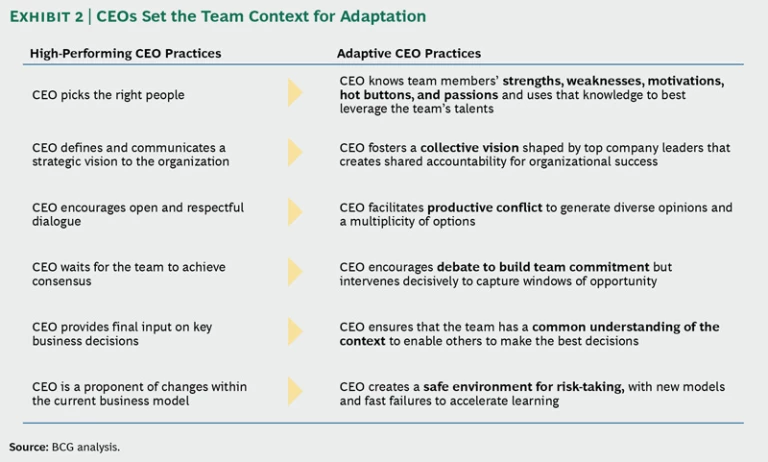

While the leadership teams in the study displayed varying degrees of shared leadership, in the most adaptive teams, the CEO plays a distinctive role in creating the team context for adaptation. These top leaders are prescient enough to know what their teams need to succeed. And they go beyond the basics to more thoughtfully use their authority and influence. “My role is about destination- and standard setting, not about dictating how everything happens,” said the division leader of a financial services company.

Recent neuroscientific research shows that learning new things activates the most energy-intensive part of the brain. Adaptive leaders understand this intuitively and are therefore dedicated to identifying and employing the most effective approaches to driving organizational learning and change. They enable people to solve problems on their own as well, and reward accomplishment with autonomy, giving individuals a way to engage in additional independent problem-solving in the future. Furthermore, the more discerning CEOs excel at practices that create a team context for successful adaptation. (See Exhibit 2 below.)

To increase the level of adaptation within a leadership team and throughout the organization, adaptive leaders can take the following steps.

- Reinforce the teamwork basics. Is your team exhibiting the basic elements of a high-performing team? These skills are the table stakes necessary to place bigger bets.

- Reflect on your relationships with each team member. Are those relationships based on empathy and mutual respect—especially among those who are most different from you?

- Assess your team’s performance on the five adaptive traits. You can measure your team either through a conversation within your leadership team or by taking BCG’s Adaptive Leadership Teams Survey (send an e-mail to altsurvey@bcg.com for more information).

Ultimately, to create competitive advantage, companies—and the senior teams that run them—require a level of adaptation that a top leader cannot accomplish alone. Leaders who understand this reality can take specific steps to enhance their ability to create teams that adapt appropriately to any business context.