Over the past decade, biopharma companies have developed cell and gene therapies, immuno-oncology, and mRNA-based vaccines, among other innovations that have significantly improved patients' health, particularly those with difficult-to-treat diseases. Such innovative therapies, which alter the course of a disease and promise long-term benefits, have raised the bar for evidence requirements. Regulators, health technology assessment (HTA) authorities, payers, health care providers (HCPs), health systems, and patients request a variety of evidence to make complex tradeoff decisions and choices.

In response, many biopharma companies have adopted integrated evidence planning (IEP) as a way to accommodate various stakeholders' needs. Each function, including clinical development, regulatory affairs, market access, medical affairs, and commercial, starts by creating an evidence-generation plan that caters to its specific external stakeholders. Then, in cross-functional sessions, they consolidate these plans into an integrated evidence plan. This approach aims to promote technical, regulatory, and commercial success while minimizing development time and cost. It requires balancing objectives and developing strategies to address the various evidence needs.

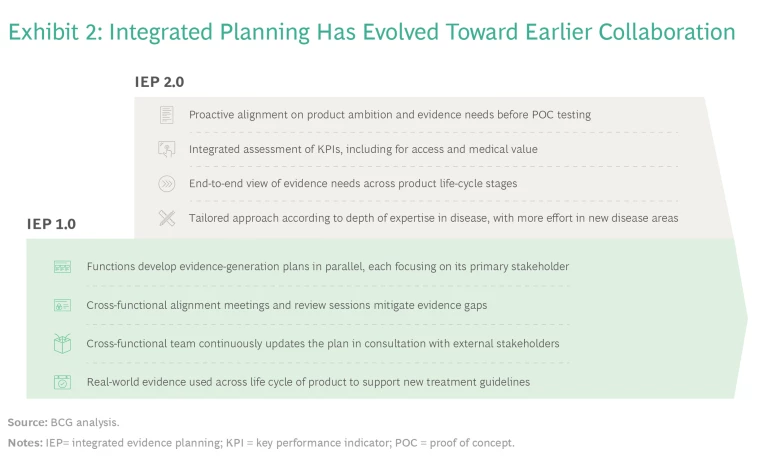

This process, which we refer to as IEP 1.0, has been a marked improvement over the traditional parallel development of functional evidence plans. Companies that have used the traditional approach without early consolidation of evidence plans often identified significant evidence gaps late in the process, which harmed the prospects for launch, reimbursement, and market uptake. By implementing IEP, cross-functional alignment, and evidence gap reviews, many companies have made significant progress.

Our recent work, however, has shown that IEP processes can be enhanced further by taking a more proactive stance: establishing a common goal for the product and the required evidence at a very early stage in the life cycle.

Our recent work has shown that IEP processes can be enhanced further by taking a more proactive stance.

To implement this enhancement, leading biopharma companies are initiating an enterprise-wide view of a new product under development before the functional planning process begins. This approach, which we call IEP 2.0, starts at an earlier phase than IEP 1.0: with cross-functional alignment on the aspirations for the product, usually when assets enter clinical development. Despite limited product data at that point, companies use their understanding of the disease, the product’s mechanism of action, and the competitive situation to assess the product’s potential—whether it should be first in disease, first in class, best in class, or a fast follower.

With a shared vision in hand, functions then can develop complementary evidence plans that build on each other, thereby avoiding duplication and early commitments to external stakeholders that might be difficult to reconcile. A common understanding also facilitates alignment among functions as they discuss how to mitigate evidence gaps that emerge along the way.

The Case for Cross-Functional Cooperation to Generate Evidence

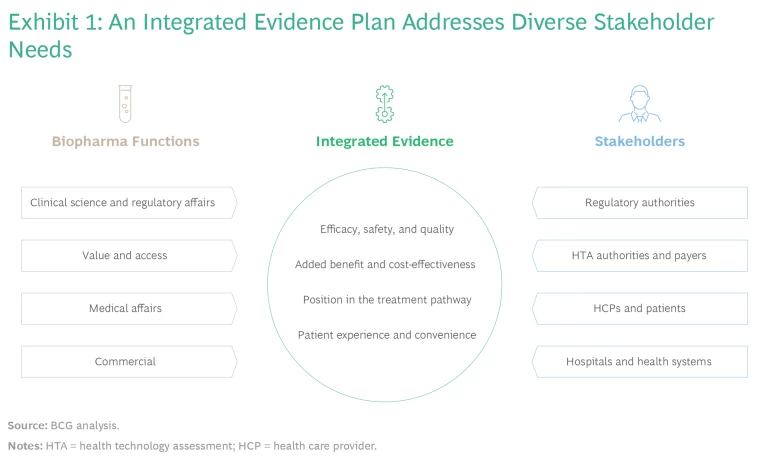

Each biopharma function generates evidence to address the requirements and evidence needs of their various respective stakeholder groups, as follows:

- Clinical science and regulatory affairs teams optimize the clinical development program to increase the likelihood of technical and regulatory success. They engage with regulatory authorities early on to design pivotal clinical trials, including aligning on the hypotheses, patient selection, comparators, primary and secondary endpoints, and appropriate duration to observe meaningful outcomes. The trial design also covers key aspects of the statistical analysis plan, such as the interim and final analyses and hierarchical testing procedures.

- Value and access teams are responsible for the clinical, economic, and humanistic evidence for submission to HTA authorities, payers, hospitals, and health systems. These stakeholders use the evidence to determine the added benefit over the current standard of care, support price negotiations, and inform coverage and reimbursement decisions. Value and access teams also seek scientific advice from HTA authorities and confirm that the clinical and modeling studies meet the methodological requirements for submission to HTA authorities. In addition, they address uncertainties relating to comparative effectiveness, long-term outcomes, treatment utilization, and budget impact at launch and over the product life cycle.

- Medical affairs teams provide information to clinical societies, HCPs, and patients about the therapy’s appropriate place in treatment to inform treatment guidelines and individual treatment decisions. They generate evidence for specific populations and medicinal uses, not all of which may have been investigated in pivotal studies. This evidence can come from company-designed studies or independent investigator-initiated studies. Medical affairs teams also document HCP and patient experiences with the product under real-world conditions, which is important information to consider in updated treatment guidelines. Like other functions, they assess any evidence gaps from the perspective of their key stakeholders in different countries.

- Commercial functions (global and within countries) seek to understand what drives competitive advantage and uptake of the product to ensure appropriate use and generate the desired financial returns. This includes understanding HCPs’ different behaviors and economics as well as patients’ out-of-pocket financial exposure. They apply this understanding to optimize the claims included in the product label, which can proactively be communicated to HCPs and patients to position the product competitively in the treatment landscape.

Although stakeholders seek evidence to answer different questions, they all rely on a core body of evidence. (See Exhibit 1.) By agreeing on common evidence requirements early, companies can streamline their evidence-generation programs, optimize the number of patients involved in investigational trials, align interactions with external stakeholders, accelerate timelines, and reduce costs.

Companies must weigh a range of methods and data sources, such as prospective randomized trials, single-arm clinical trials, real-world data analysis, observational research, and modeling or simulation studies. These approaches provide complementary insights but vary with respect to investment levels, timelines, ability to attribute causality, and internal and external validity. An upfront agreement helps companies select the right approach to best meet their goals.

When such early alignment doesn't happen, each function initiates planning and invests significant resources into their respective evidence-generation plans, which then need to be consolidated in cross-functional meetings. These sessions typically take place after proof of concept (POC) has been established, but before investment decisions for large-scale pivotal studies. At this stage, many aspects of the functional plans are quite advanced. Functions may have independently reached out to and received advice from regulators, investigators, and HTA authorities and payers, and agreed on the details of clinical trials with them. As a result, cross-functional sessions tend to be focused on tradeoffs to accommodate the needs of different stakeholders, rather than creating the best possible evidence plan. In many situations, we have seen this lead to functional representatives defending their assessments instead of sharing their expertise and stakeholder insights.

Lack of upfront alignment affects downstream activities such as transparency, collaboration, and alignment as evidence-generation plans are executed. Functions sometimes even fail to keep their colleagues informed about changes and issues, such as timeline adjustments, trial amendments, and expected trial outcomes. To increase transparency across functions and between global and local teams, companies have introduced an “evidence gap review” as a part of annual planning. While a company-wide review is an important step and does indeed address some of the challenges identified, the typical parallel approach and functional accountability may still hinder fully integrated evidence planning.

Although stakeholders seek evidence to answer different questions, they all rely on a core body of evidence.

IEP 2.0: Initiating Cross-Functional Alignment Up Front

By shifting the focus from developing and consolidating functional plans to defining an upfront enterprise-wide perspective, IEP 2.0 helps companies understand what it takes for the asset to be successful and what will be needed for evidence planning. The approach starts as early as possible in the development process—typically at the end of research before the decision to initiate the first studies in human subjects. It begins with a holistic cross-functional assessment of the product’s potential and the company’s ambition for its development and commercialization. Once leaders have established enterprise-wide alignment on the product strategy, the functions co-create the integrated evidence plan based on their shared objectives for the core evidence. Each function then focuses on identifying the additional evidence required for its respective stakeholders and uses the insights to continuously update the core evidence plan. (See Exhibit 2.)

Using this approach allows functions to avoid unnecessary conflicts, such as commitments to regulators on the choice of comparator or endpoints for pivotal studies that might not meet the expectations of HTA authorities and payers, and vice versa. Our experience shows that these stakeholders are indeed flexible and agree on a common choice of comparator or endpoint if they understand the concerns and expectations of other parties.

The proactive approach also helps to promote mutual understanding and appreciation among internal and external experts on humanistic endpoints, such as patients’ quality of life, function, behavior, and the implications for their families and caregivers. These endpoints often are more important for patients and HTA authorities than regulators. The inclusion of additional endpoints, including patient-reported outcomes, can increase costs and potentially delay time to market. Although this conflicts with companies’ goals to manage spending and accelerate the product launch, it often improves the chances for reimbursement and uptake. Including these endpoints, therefore, typically requires tradeoff decisions in clinical-trial design and subsequent evidence-generation planning.

As POC and early-development studies read out, the cross-functional team reviews and updates the plan, leading to a critical investment decision regarding whether to proceed with full development and pivotal studies. In turn, the results of pivotal studies may lead the organization to revise its ambition for the product. In some respects, the product may perform better than expected. In other respects, however, studies may fail to confirm initial hypotheses, and the organization must identify any gaps in the evidence and seek to mitigate them. The process does not stop at marketing authorization and access—it continues throughout the life cycle as HCPs gain experience with the treatment, new indications are developed, and new competitors enter the market.

The process does not stop at marketing authorization and access—it continues throughout the life cycle as HCPs gain experience with the treatment, new indications are developed, and new competitors enter the market.

The Five Stages of IEP 2.0

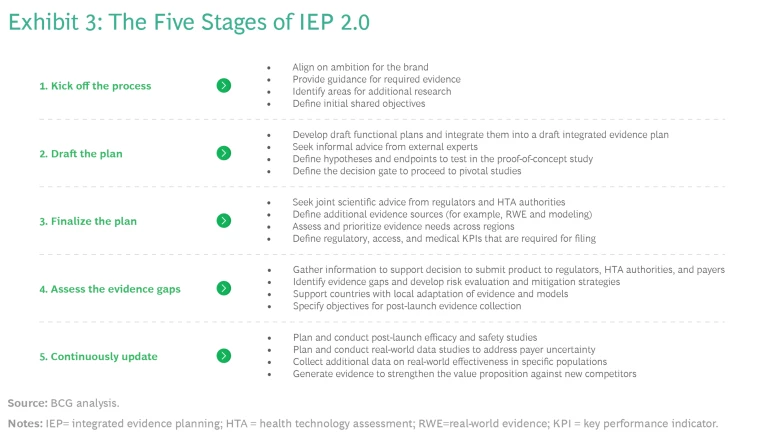

A set of activities across the development process provide the structure for IEP 2.0. (See Exhibit 3.)

1. Kick Off the IEP Process Before First-in-Human Studies.

Because the process of IEP 2.0 kicks off before first-in-human studies, there is limited information about the product’s efficacy and safety. That is why functions should focus on testing their understanding of the disease area and the respective stakeholder requirements. If the company has significant experience in this area, little additional work may be needed. But for companies new to a new disease area, the cross-functional team may want to conduct research into the epidemiology, disease history, and relevant subpopulations. They may also want to explore suitable endpoints and their properties—issues include whether endpoints have been validated and the minimum clinically important differences have been established, as well as the appropriate time to measure them.

To align on ambitions for the brand, provide guidance for the required evidence, and define shared objectives, the cross-functional team should answer the following questions:

- What is the unmet need, as derived from the patient journey and treatment guidelines?

- What is the scientific rationale for asserting that this product can address the unmet need?

- Which of the following is our ambition for the product?

- A first-in-disease therapy, for which we need to establish the epidemiology and natural history of the disease and align on new endpoints and treatment paradigms

- A first-in-class therapy that offers a new mechanism of action for an existing standard of care that has already demonstrated long-term efficacy and safety

- A best-in-class therapy that demonstrates added patient benefits on existing endpoints relative to a therapy that may have only recently entered the market

- A fast-follower therapy that is differentiated by tolerability, administration, and patient experience rather than clinical benefits

- Which patient groups, including vulnerable or marginalized populations, must we include in our clinical studies?

- What is the potential to address equity and affordability issues by developing product versions that are easy to administer in regions with limited treatment capacity or tropical climates that require heat-stable formulations?

- What do we need to demonstrate to persuade each stakeholder that we have achieved our ambition for the product?

Cross-functional team participants will benefit from a discussion guide that facilitates these explorations. Participants also should have a deep understanding of patient and HCP journeys and existing treatment guidelines, as a foundation for discussion. The internal discussions should be complemented by perspectives of select external experts.

2. Draft the Integrated Evidence Plan Before Proof-of-Concept Studies.

After the completion of first-in-human studies, companies prepare for the decision to initiate POC studies. Functions address any gaps in their understanding of the patient journey and patient-relevant endpoints. They define key aspects of clinical trial design, often obtaining informal advice from external experts, and develop their draft evidence plans. Because there is a common understanding of the overall ambition for the brand, functional evidence plans can be aligned in a draft integrated evidence plan. This process will provide a more refined perspective on which hypotheses and endpoints need to be tested against relevant comparators in specific patient populations and how the company should accordingly design the clinical trial.

Because there is a common understanding of the overall ambition for the brand, functional evidence plans can be aligned in a draft integrated evidence plan.

Drafting the integrated evidence plan will also require a common understanding of how to balance the breadth and depth of the evidence-generation program with time and budget constraints. Agreeing on these aspects allows functions to understand the overall objectives, refine their initial plans, make informed decisions, and ensure that POC studies provide valuable information for designing pivotal studies.

At this stage, companies will often reach out to external experts and stakeholders to validate internal assumptions and how these are reflected in the draft evidence plan. They will also agree on decision gates to proceed to pivotal studies. This includes setting the minimum criteria for determining that the POC study was successful and advancing the product to the next stage of the IEP process. Teams should also establish the criteria for determining that the POC study has failed and there is no basis to continue developing the product, at least for the indication that was tested. For study outcomes that do not meet either set of criteria, the company must identify the additional data it needs to collect before proceeding to the final integrated evidence plan and investment decision.

3. Finalize the Integrated Evidence Plan Before Proceeding to Pivotal Studies.

The availability of positive POC data triggers preparation for the decision to invest in the product’s full development. Functions need to agree on a comprehensive integrated evidence plan and how it will be supported by functional plans. They determine hypotheses and endpoints to test in pivotal trials and identify the additional evidence sources, such as real-world evidence and modeling.

Again, this is best done through a co-creation process that takes a holistic perspective on the product. Key actions include:

- Maintain a shared enterprise view. The organization should consider the product’s potential from scientific, competitive, and commercial perspectives—for the initial indication and possible future indications.

- Seek joint scientific advice from all stakeholders. Regulators, HTA authorities, and payers have different decision contexts and evidence requirements. Companies that use IEP 1.0 often seek scientific advice from them separately. They may find that regulators specify a preferred comparator, endpoint, or trial design that is difficult to align with HTA authority and payer expectations, or vice versa. Bringing all stakeholders to the same table typically reveals that they have a fair amount of flexibility, which leads to an aligned evidence program that addresses the needs of all groups.

- Consider real-world evidence. Well-designed randomized clinical trials are still the cornerstone of clinical development. Regulators, HTA authorities, and payers consider them to provide the gold standard of evidence. However, high-quality real-world evidence is increasingly available—such as for rare diseases with high levels of unmet needs and a scarcity of patients—and many stakeholders accept it to complement traditional clinical trials.

- Assess and prioritize evidence needs across regions. Demonstrating additional benefits relative to locally relevant comparators (for example, in Germany) may affect the size of the development program and consequent speed to market in key regions (such as the US). Companies must understand the different regional needs and assess the tradeoffs in deciding which region’s requirements to prioritize.

Bringing all stakeholders to the same table typically reveals that they have a fair amount of flexibility, which leads to an aligned evidence program that addresses the needs of all groups.

Companies have traditionally formulated clear KPIs related to regulatory approval of the product and what it takes to win in a competitive marketplace. In addition, companies should define KPIs for evidence development, focusing on access and medical value. Such KPIs are typically linked to achieving the desired added-benefit rating from HTA authorities and payers and providing relevant information that allows clinical societies to appropriately consider the new therapy in their treatment guidelines. (See “Focus on KPIs for Access and Medical Value.”)

Focus on KPIs for Access and Medical Value

- Access. As companies shift the goal of evidence planning from regulatory approval to reimbursement in key jurisdictions, pricing becomes more important. However, the typical pricing KPIs, such as price achieved and time to reimbursement, are outside the control of clinical development, regulatory, and medical affairs organizations. One way to facilitate setting a common evidence-generation goal is to clearly articulate the desired “added-benefit rating” in the TPP. Many national regulators, including the HAS in France and the GBA in Germany, have defined such ratings. In the US, an independent organization, ICER, provides benefit ratings. Because added-benefit ratings are based on the product’s clinical value, they are useful to the development, regulatory, and medical communities.

- Medical Value. An important outcome of evidence generation is providing information that clinical scientific organizations require to update their treatment guidelines. To create an evidence-generation goal, the medical value KPI should specify the desired position in the treatment pathway that is set out in the clinical guidelines, clinical pathways, and payers’ medical policies.

4. Assess and Mitigate Any Evidence Gaps Before Regulatory and HTA Submission.

After pivotal studies have read out, the company decides whether to submit the therapy to regulators for approval, and to HTA authorities and payers for coverage, price negotiations, and reimbursement. This will require a detailed assessment of the extent to which the data support the company’s and stakeholders’ expectations regarding the benefit-risk tradeoff and the effectiveness and safety relative to the current standard of care. It is important at this stage to identify any evidence gaps and prepare risk evaluation and mitigation strategies. For many products, uncertainty may exist regarding long-term outcomes and which patients will have the best response. This can be addressed through performance-based payment contracts and postlaunch evidence collection. The global organization will also work closely with affiliates to adopt evidence and models for local use.

Upon reaching this stage (or even during stage 3), most companies include a review of the integrated evidence plan as a part of the annual planning cycle. The goal is to maintain a running tally of the existing and newly arising evidence gaps and define clear plans to mitigate them, including objectives for post-launch evidence collection. Conducting this review during the annual planning process allows everyone in the organization, from global functions to country leaders, to have a common view of evidence needs and the plans for the product.

5. Continuously Update the Integrated Evidence Plan Throughout the Life Cycle.

The IEP process does not end with marketing authorization and access. Once the product is on the market, there are many requirements and opportunities to generate additional evidence in clinical trials and, more importantly, based on clinical experience and the product’s use in real-world conditions. For example:

- Regulators may require a company to further study a product’s long-term efficacy and safety.

- HTA authorities and payers may identify uncertainties relating to the clinical evidence that affect their ability or willingness to cover the product and determine the price.

- Routine clinical practice may identify and investigate new or optimized uses of the product—in particular, using the product in combination or sequence with other products.

- New therapies (in-class or out-of-class mechanisms of action) may be approved for the product’s indication, making it necessary for the company to update the product’s value proposition to compete against these alternatives.

- Payers and HTA authorities will regularly reassess the product’s added benefit, coverage conditions, and prices over the life cycle, which is common practice in many European countries. This will also become important in the US as recent legislation empowers regulators to negotiate prices for high-cost drugs covered by Medicare after they are on the market for nine years (for small molecules) or 13 years (for large molecules).

To generate the required evidence, companies will need to plan and conduct post-launch efficacy and safety studies as well as collect additional data on real-world comparative effectiveness in specific populations.

The IEP process does not end with marketing authorization and access.

Annual reviews should continue throughout the product life cycle. This allows companies to assess additional evidence-generation requirements that emerge in connection with key events (such as new data readouts from internal studies or competitors’ moves) and define plans to address them.

Subscribe to our Health Care Industry E-Alert.

Addressing the Practicalities of Implementing IEP

As companies consider implementing IEP, they are confronted by two practical constraints that they need to address simultaneously: First, they have products at different life-cycle stages, from early-pipeline to on-market products. Second, they must take a comprehensive approach while not overburdening the organization as it launches IEP.

Based on our experience, companies should consider the following actions to address these practicalities:

- Start implementation by focusing on a select group of early-pipeline, late-stage, and on-market products before scaling across your entire portfolio. A staged approach provides opportunities to foster the significant mindset and behavioral changes required for successful full-scale implementation. It also allows the organization to iron out the kinks in the initiation process for early-stage assets and of the annual review process for later-stage assets.

- Do not compromise on creating a shared objective across all functions and a clearly articulated evidence ambition at the product level. This will enable all functions to detail their respective evidence plans with a true enterprise-wide mindset.

- Specify the right metrics for access and medical value in the TPP, in addition to traditional KPIs on clinical trial and regulatory success.

- Take a long-term perspective. This includes considering future indications of a product and understanding the unique needs of traditionally marginalized populations and regions with differing levels of treatment capacity and affordability.

- Consider all sources of evidence, including increasingly available real-world evidence and evidence obtained from advanced modeling and simulation.

- Ensure that all functions understand that the organization needs to continuously generate evidence and make appropriate tradeoffs between speed to market and developing a comprehensive data package.

Start implementation by focusing on a select group of early-pipeline, late-stage, and on-market products before scaling across your entire portfolio.

Companies can implement IEP for products anywhere along the life cycle. For products that are already in advanced stages of development or on the market, IEP 1.0 is important for addressing the evidence requirements for all stakeholders and mitigating any evidence gaps. This is particularly valuable for products that face the greatest evidence challenges. For products that are transitioning from research into development, we recommend initiating IEP 2.0. Success requires early cross-functional collaboration and engagement with regulatory authorities, HTA authorities, payers, clinical societies, and patient representatives. By implementing IEP at scale, companies will more likely help patients in disease areas with high unmet needs to receive the transformational benefits of innovative therapies.