Increasing a nation’s wealth is hard; using that wealth to improve the well-being of citizens is harder still. In recent years, Peru has made significant progress on both fronts, as evidenced by The Boston Consulting Group’s most recent Sustainable Economic Development Assessment (SEDA). In terms of both income level and overall well-being, Peru stands slightly below the median for the 163 countries in the SEDA analysis.

Given that a new government is beginning its administration, this is an opportune time for Peru to assess where it stands and to highlight the areas in which concerted effort to make improvements can have an outsize impact in converting the country’s increasing wealth into greater well-being. In this regard, SEDA provides insights that will help set priorities and identify relevant best practices. (See the sidebar “Defining and Measuring Well-Being.”)

DEFINING AND MEASURING WELL-BEING

SEDA defines well-being through three elements that comprise ten dimensions. (See the exhibit.) The first element is economics, which gauges a country’s performance in generating balanced growth through income, economic stability, and employment. That balanced growth provides a basis for the country to invest in the other two elements.

The second element is investments, which includes health, education, and infrastructure. These categories—major items in any government budget—encompass short- and long-term investments that help drive improvements in both economic growth and well-being over time.

The third is sustainability. The term “sustainability” usually refers to the environment, but it can encompass issues related to social inclusion. In the SEDA sustainability element, we include both the environment dimension and social inclusion (which comprises the dimensions of income equality, civil society, and governance). A robust score in this element typically reflects sound policy decisions rather than large budgets. And strong performance here tends to increase a country’s ability to sustain gains in well-being, while weakness in any of the dimensions can limit a country’s well-being down the road.

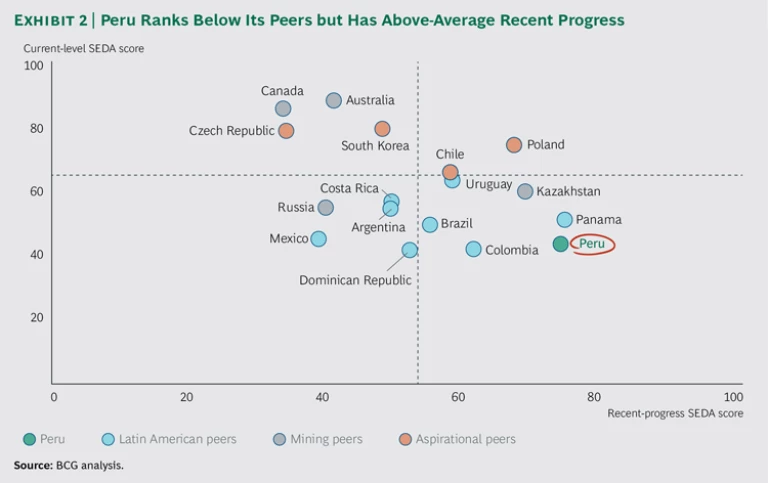

We use indicators for each dimension to generate scores that reflect a country’s current level of, and recent progress in, well-being. Our recent-progress measure tracks how well-being has changed. For our 2016 analysis, we used data from 2006 through 2014. Current-level scores—both overall and by dimension—tend to be fairly stable, because they reflect decades of investment and development. Recent-progress scores tend to be more dynamic.

SEDA does not measure well-being in absolute terms: both current-level and recent-progress scores—overall and by dimension—are measured on a scale of 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest). The median scores1 for other countries in our data set can then be used to assess how a country stacks up in a given area against a peer group or the rest of the world.

Of course, wealth has a direct bearing on well-being. SEDA examines this connection by looking at a country’s current level of well-being relative to income levels and at recent changes in well-being relative to economic growth. These relationships are reflected in two metrics:

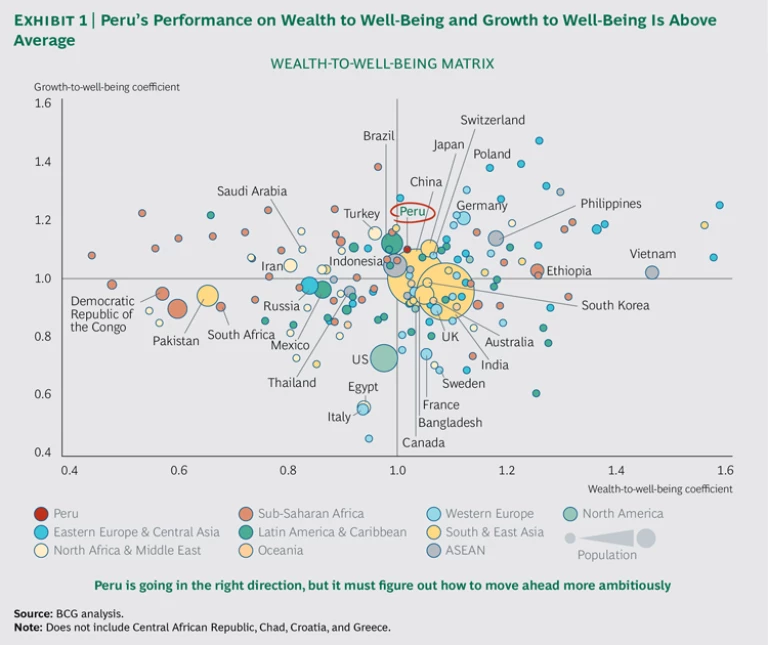

- The wealth-to-well-being coefficient compares a country’s current-level SEDA score with the score that would be expected given the country’s GDP per capita. The expected current-level score is based on the relationship between GDP per capita and current-level well-being scores among all countries in our analysis. The coefficient thus provides a relative indicator of how well a country has converted its wealth into the well-being of its population. Countries that have a coefficient greater than 1.0 deliver higher levels of well-being than would be expected given their GDP levels, while those with a coefficient below 1.0 deliver lower levels than expected.

- The growth-to-well-being coefficient compares a country’s SEDA score for recent progress with the score that would be expected given the country’s GDP growth rate. The expected score is based on the average relationship between recent-progress scores and GDP growth rates during the same period for all countries. The coefficient therefore shows how well a country has translated income growth into well-being improvements. As with the wealth-to-well-being coefficient, countries that have a coefficient greater than 1.0 are producing improvements in well-being beyond what would be expected given their GDP growth rate from 2006 through 2014.

Peru’s Challenges Today and Priorities for a Better Tomorrow

Peru is roughly average in converting its wealth into well-being. Looking at recent progress, however, Peru has relatively high and stable economic growth, and, most important from our perspective, it has converted its economic gains into well-being improvements at a rate that is also above the global average. (See Exhibit 1.)

Peru has a powerful asset in its economy, which has outpaced regional peers and demonstrated solid growth over the past 15 years, including the period following the 2008 global recession. Growth has been driven primarily by two factors, private consumption and increasing investment, and has been complemented by a significant drop in poverty and an expansion of the middle class.

Despite this progress, Peru’s GDP per capita lags behind the region’s average and is far below that of some countries of comparable size and geographic and economic characteristics. The same is true of productivity (measured as GDP per person employed): Peru is almost 30% below the average for Latin America.

Peru’s economy evidences increasing balance and diversity, but there is room for further improvement, especially in the country’s import-export structure. Mining represents about 10% of GDP but more than half of total exports. The country is heavily exposed to fluctuations in commodity prices. Exports are highly concentrated in non-value-added, mostly mined, products, as well as in nontraditional exports.

Previous efforts to diversify Peru’s economy have had mixed results, but some industries—including metal mechanics, agriculture, and tourism—have experienced significant progress. A combination of further infrastructure development, sound public policy, a focus on value-added activity, and increasing attention to exports is needed to accelerate further growth.

The economy is also highly centralized geographically. Lima, home to 33% of the country’s population, accounts for half the country’s GDP. Lack of physical infrastructure outside the capital leads to high logistics costs in the other regions.

The country still faces wide regional variations in economic and social well-being; social indicators for some regions in Peru are among the lowest worldwide. Some regions suffer from an alarming lack of access to basic infrastructure, such as water, electricity, and roads. Education is highly uneven and the system does not serve the needs of the country or its economy. There are also big regional gaps in health indicators.

Peru also has a large informal economy, the second largest in Latin America in relative terms. This is an inhibiting factor for growth, a constraint on government revenues to fund critical initiatives (such as health and education), a facilitator of crime and corruption, and a drag on productivity. On the other hand, low public debt and sound economic management have enabled the country to mitigate volatility and financial risk.

SEDA’s Insights

Peru faces plenty of challenges in terms of both wealth and well-being, as would be expected of any country at a similar stage of development. The questions are, where and how should Peru apply its resources to maintain, or even accelerate, the progress of recent years? How can the country best continue to fuel economic growth and convert its increasing wealth into improvements in well-being for citizens?

We used SEDA to examine three of Peru’s peer groups:

- Latin American peers. This group comprises countries in the region with similar economic and social circumstances: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Panama, and Uruguay. These countries have democratic governments, an average population of 53 million (compared with Peru’s 31 million), and GDP per capita that is equal to or higher than Peru’s $12,402 (the average in this peer group was $17,717).

2 2 Unless otherwise noted, all GDP figures in this report date from 2015 and are calculated using current dollars, adjusted for purchasing-power parity. - Mining peers. Like Peru, the countries in this group depend substantially on metals and mineral extraction. They represent much of the worldwide production of commodities such as copper, gold, and silver. They have average populations of 46 million and average GDP per capita of $31,434. This group comprises Australia, Canada, Chile, Kazakhstan, Poland, and Russia.

- Aspirational peers. These countries have populations and economies that are similar in size to those of Peru, but they have levels of wealth that are higher than Peru’s and above-average records of converting wealth into well-being. Their per-capita GDPs are between 100% and 300% of Peru’s, and their economies are growing. The average size of their populations is 29 million, and their average GDP per capita is $28,792. This group comprises Chile, the Czech Republic, Poland, and South Korea.

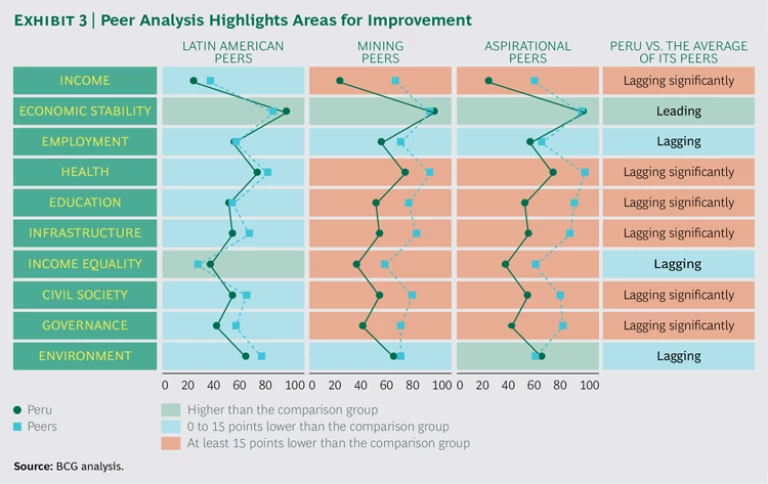

As is the case in the global rankings, Peru’s performance on many of SEDA’s dimensions trails those of its peers, but it has outperformed in recent progress. (See Exhibit 2.) More tellingly, the peer comparison highlights multiple areas in which Peru lags its peers, including income, infrastructure, education, health, governance, and civil society. (See Exhibit 3.) Peru needs to further boost economic growth and reduce its reliance on mining. There is an urgent need to step up investment in infrastructure, which has widespread economic and social benefits. A combination of investment and improved performance, quality, and efficiency is also urgently needed in health care and education. Shrinking the gaps in these areas would set Peru on a path to achieving strong improvements in the well-being of its citizens. A prerequisite, of course, is that Peru maintains its momentum in economic growth.

In addition, Peru needs to address the problems in governance and civil society that can undermine and limit the effectiveness of efforts in other areas. Two of the biggest issues are crime and corruption. Peru has one of the highest crime rates in the Americas. And according to the National Audit Office, Peru loses some $3 billion a year to corruption—which is probably just the tip of the iceberg.

The Need for Economic Diversification

To sustain growth and reduce exposure to commodity price volatility, Peru needs to broaden its economic base. We believe that a combination of private investment and structured, noninvasive public participation can help accelerate this process.

BCG has developed a framework—a hierarchy of interventions—that helps guide public participation toward economic development and diversification. The framework consists of five levels of public action that involve both increasingly sharp targeting and decreasing cost-effectiveness.

The bottom two levels aim to remove barriers and generate healthy conditions for new industries to thrive at an economy-wide level. The business environment in a developing country such as Peru can be a significant obstacle to diversification and economic growth, particularly for small and midsize enterprises (SMEs), which are often the engine of economic and job growth. Time-consuming and outmoded local regulations also lead to government inefficiencies. These policies and ways of working need to be updated and shaped according to actual needs.

Governments can also help further economic development and diversification by facilitating business creation and expansion through, for example, improving capabilities (such as policies that encourage innovation and use of technology) and lowering the cost of doing business. BCG research in 2015 in six countries found that narrowing the “mobile divide” between SME leaders and laggards in the use of mobile technologies could add 7 million jobs over three years, increase GDP growth by 0.5 percentage points, and help reduce unemployment by more than 10%. (See The Mobile Revolution: How Mobile Technologies Drive a Trillion-Dollar Impact, BCG report, January 2015.)

The top three levels of intervention focus on supporting and fostering particular industries or sectors that have naturally emerged as candidates for economic development and diversification, such as tourism, metal mechanics, logistics, forestry and aquaculture, and creative and gastronomic endeavors. Targeted training and infrastructure initiatives are two important ways to support such industries.

Targeted incentives are another effective means of encouraging the development of an economic sector and promoting economic growth and diversification. The best incentives can be supported by government or public institutions, but, critically, they also have an important private-sector component, such as matching funds and guarantees.

Subsidies constitute the highest level of public participation and represent one of the greatest levels of intervention that a government can have in the market. Subsidies should be used sparingly because they can easily introduce distortions and build detrimental dependencies. The most common way to provide subsidies is through tax benefits and cash relief.

Infrastructure: Building Out the Basics

Improving infrastructure—physical, electrical, telecommunications, and increasingly, digital—is a major and essential challenge for Peru. Despite recent advances, the country lags behind its peers in both spending and development. In the World Economic Forum’s global competitiveness ranking, Peru scores 89 out of 140 for infrastructure, far worse than its peers’ average.

Peru faces an estimated infrastructure gap of some $160 billion from 2016 to 2025, with transportation, energy, and telecommunications making up almost three-quarters of the shortfall. Worse, while the government has a national strategy to guide infrastructure development through 2021 that includes a regional development and infrastructure section, actual development plans are in place for only the rail network, rural electrification, and sanitation. There are no development plans today for telecommunications, health care, or education.

If Peru’s government is going to close the financing gap and meet the country’s infrastructure needs, it will need to take four actions.

Set priorities and put a plan in place. Peru must prioritize projects according to its most critical requirements and develop an integrated, multisector national infrastructure plan. Peru also needs to reassess its current infrastructure project pipeline and supporting policies in the context of a national infrastructure plan that integrates four elements:

- A long-term vision balancing key infrastructure needs and available resources

- Medium-term goals providing coordinated, outcome-based targets for progress that are consistent with the long-term vision

- A project and privatization pipeline encompassing both public projects and public-private partnerships (PPPs), including privatization options, that invest in existing and new infrastructure required to achieve the medium-term goals

- Priority policy interventions supporting public and private investment to deliver the pipeline

Establish a single agency for approvals. Peru needs a properly resourced agency accountable for the overall infrastructure-project approval process. The agency must allocate responsibilities between local and regional governments and the Ministry of Economy and Finance. Digital processes can help reduce paperwork and increase transparency.

Increase incentives for PPPs. To close the infrastructure gap, Peru needs to generate annual infrastructure financing equivalent to almost 5% of GDP through 2025. PPPs may offer the highest potential for closing the financing gap as Peru is one of the most predisposed countries toward PPPs in Latin America.

Define clear rules and develop a best-practice framework. Peru has no laws with which to enforce private company performance on infrastructure projects or to penalize government agencies that do not comply with requirements. The country urgently needs to define clear rules and sanctions to motivate the government to work with private-sector enterprises in order to move projects forward and ensure that private companies’ priorities are aligned with the government’s needs. Increasing transparency in negotiations after a project’s approval is another priority. BCG and the World Economic Forum have developed a best-practice framework for PPPs that is based on a study of successful international PPP models. Using this framework to assess Peru’s performance in the various aspects of project execution against a global benchmarking database could improve project design and policy settings, and increase the support of multilateral agencies.

Extending Health Care to All

Despite good progress in recent years, health care remains a big challenge for Peru. In the SEDA ranking, Peru ranks 96th out of 163 countries in its current level of health care, but it ranks 65th in recent progress. Peru trails its peers, often significantly, in multiple measures, including hospital beds, immunization of children, incidence of tuberculosis, and physician density.

Regional disparity in health care coverage remains a serious problem. Service is another factor. Among the many issues the typical patient faces are long wait times for both primary and specialized care, a high level of bureaucracy throughout the health care system, and constant shortages of medicines. A big part of the problem is the absence of a program to evaluate the health care system, which could help the government identify problem areas and develop remedial initiatives.

Peru needs to take the following three actions if it is to register significant improvement in health care.

Increase funding. To create fiscal room for increasing health care expenditures, Peru must expand its public revenue base and improve its tax collection system, including capturing contributions from informal workers. Imposing targeted taxes on such products as tobacco and alcoholic beverages could also help.

Expand coverage. Peru needs to expand coverage and improve service, especially in underserved regions. The government should analyze and prioritize regions for the assignment of resources, both human and infrastructure, to reduce the current gaps. PPPs can help close the infrastructure gap, particularly with respect to hospitals, which can be built and run by private players. The government should develop campaigns to encourage and facilitate health-related careers to improve physician density. New technologies and business model innovations, such as telemedicine and mobile health, can also help.

Improve quality and service. Peru needs a health-care-system evaluation program with clear KPIs, including those for methodology and frequency of assessment. Effective use of digital technologies can reduce bureaucracy, deliver better service, and improve resource planning.

Education: A Prerequisite to Growth and Well-Being

Despite big strides in education in recent years, Peru trails its peers on multiple measures, including years of schooling, tertiary enrollment, and math and science scores. As with other measures of wealth and well-being, there is significant regional variance in education, and some cities score much worse than others.

Peru has halved its illiteracy rate (to 5.5% in 2015), increased secondary-school enrollment (to 78% in 2014), and shown significant increases in early-primary-school-knowledge test scores from 2012 through 2015. But the country’s illiteracy rate is 3.3 percentage points higher than the average of Peru’s peers, secondary-school enrollment is 8 percentage points lower than its peers and the country lags considerably in its scores on the global Programme for International Student Assessment.

Young students are not spending enough time in school: only 46% of early-education schools comply with minimum classroom hours. Peru is also behind the times with respect to basic tools such as textbooks and technology. Schools, curricula, and programs in Peru do not necessarily promote the skills needed by workers in the Peruvian economy, which has a big shortage of skilled workers. This holds back both individual incomes and national growth.

One of the main reasons that Peru trails its peers in education is funding. The country spends only 3.7% of GDP on education, well below the peer average of 4.5%.

In addition, education policy is set at the national level, but regional and local governments have substantial flexibility in implementation, which results in inconsistent content and the lack of a standardized program nationwide. Peru also has a problem with both the quantity and the quality of its teachers. At current rates, the country will face a shortage of more than 157,000 teachers by 2021. And less than 15% of teachers nationwide passed the most recent test given by the Ministry of Education.

Peru can make rapid strides with four actions.

Tighten management and quality control. Peru needs to tighten the administration and management of the education system. In our assessment, the most effective systems operate as so-called closed-loop instructional systems. They base curriculum, strategy, and instruction directly on educational objectives. They embed frequent and ongoing evaluation into the system and provide for appropriate interventions. Perhaps most important, they track outcomes and learnings, which are used to modify or adjust objectives.

The government can also reduce bureaucracy in the education structure, moving toward lean organizations and processes, and limit local and regional governments’ ability to change the content of educational programs. One concrete step is to empower the Superintendencia Nacional de Educación Superior Universitaria to regulate the quality of tertiary education.

There is a major need to standardize educational materials across regions and to employ digital technologies much more widely to improve materials and their use.

Focus on needed skills. Peru must focus its programs and content on high-impact areas. Germany offers a model for consideration: its dual-track system provides both general and vocational paths.

Address infrastructure. Peru needs a national multistage education infrastructure plan. A government entity should be in charge of setting priorities and making investment decisions. PPPs can play a role, especially if projects are grouped so that there are sufficient volumes of work to attract private investment, which could also result in lower costs for government.

Motivate teachers and teacher development with incentives. Peru desperately needs a new teacher evaluation system that is focused on professional development and has multiple evaluation sources. The system can use digital tools to increase scope, ease the learning process, and obtain accurate information about performance. Peru also needs to continue current efforts to make teaching more attractive by increasing salaries and using incentives such as bonuses to reward performance and to encourage teachers to work in rural and other underserved areas.

Moving Forward

Successful countries do a few things very well when it comes to sustainable development. Perhaps most important, they prioritize aggressively, make smart investments in high-impact projects and initiatives, and ensure that government is a leader—not a follower—on economic and sustainability issues.

These are powerful prescriptions for a country such as Peru, which is on the right track and making strong progress but needs to step up its efforts aggressively if it wants to move out of the middle of the pack and into the ranks of its more prosperous and productive peers. By targeting the right areas—including economic diversification, infrastructure, health, and education—Peru can continue to make, and accelerate, gains.