If generals—relying on the strategies that worked in the past—often fight the last war, is it any surprise that leaders look into the rear-view mirror to find their future leaders? This approach may have worked before but has become the modern-day Maginot line of leadership.

For most of the twentieth century, leaders led through variations of command and control. That hierarchical, inward-focused style began to unravel at the end of the century. Still appropriate in certain situations, it is increasingly being displaced. But what leadership style will emerge in this still young century? To understand future leadership requirements, The Boston Consulting Group recently interviewed nearly 30 senior HR executives from around the

Several of them mentioned the changing military model. Today’s wars incorporate elements of nation building and social-service delivery. The battleground is uncertain and ambiguous. Successful military leaders must empower field personnel able to receive and interpret conflicting signals. Likewise, corporate leaders confront an increasingly complex, interconnected, and fast-moving world in which nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), social networking, and low-cost competitors all share the stage.

These executives identified six fundamental business changes that create a need for new leadership skills:

- Intensified global and local competition

- Increasing importance of multiple stakeholders

- Faster rate of information and innovation

- Greater uncertainty and ambiguity

- Greater emphasis on corporate social responsibility

- Greater need for virtual teams that transcend an organization’s boundaries

These shifts are well known, but their ramifications for leadership are not well understood. Leaders need to be prepared for the future rather than stuck in the past.

Defining the New Leader

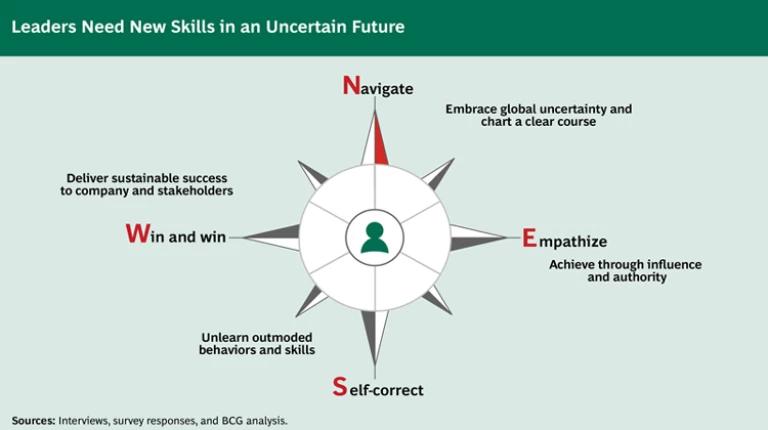

Certain attributes of leadership are timeless. Integrity, courage, judgment, intelligence, vision, and ambition all still matter but will be insufficient in the future. Four additional skills or qualities are needed now. (See the exhibit.)

As a first step, leaders need to be able to navigate through this kaleidoscopic environment. They need to convey purpose and direction but also be willing to make midcourse corrections. They need analytical skills, as always, but also the ability to discern and translate signals and make decisions on the basis of both experience and imperfect information about the future.

Second, leaders need to empathize with people, understand perspectives different from their own, and build networks with people outside of their organization. This skill is critical in dealing with NGOs, regulators, and other bodies that are now participating more actively in business. It will also help companies enter developing markets—the font of future growth, where customer needs, expectations, and the willingness to pay can be quite different from in the West.

Third, leaders need to be willing to self-correct. This skill has less to do with fine-tuning strategy than with revisiting their personal and long-held assumptions about business leadership and success. Leaders need to question the status quo, be willing to reexamine the environment, and correct outdated modes of leadership. It is tricky to balance this questioning stance with the confidence that leaders need to convey.

Finally, leaders need to win and win. In other words, they should broaden their view of success in a world of greater government involvement, globalization, and interconnections. Success is no longer a zero-sum game. Companies increasingly are partnering with competitors, cooperating with regulators and NGOs, and entering markets where they may not be well known. Their success will increasingly depend on other parties rather than coming at their expense.

Developing the New Leader

It is always easier to describe the future than to shape it. Companies are busily trying to create new mechanisms to identify, develop, and retain future leaders—and create new leadership metrics and processes. All of these changes are works in progress.

In our interviews, ten cutting-edge practices, grouped around three broad themes, emerged from the more than 100 identified leadership requirements. They are a good starting place for thinking about leadership in a new and necessary way.

Expand horizons

1. Require broad-based experience from future leaders, such as rotations through two functions, two business units, and two geographic regions

2. Immerse leaders completely in unfamiliar markets by requiring them, for example, to work in rural India

3. Temporarily assign leaders to external groups, such as industry groups, NGOs, and government panels

4. Embed social causes into the business in order to generate loyalty among leaders

Create fast tracks

5. Provide opportunities for high-potential leaders to “skip a chair” in order to advance their career

6. Create a “critical assignments bank” to develop next-generation leaders and to allow older leaders to make valuable contributions late in their career

Accelerate skills development

7. Identify and map top talent in key markets and benchmark yourself against the best

8. Offer experiences in which leadership must be shared, such as joint ventures and partnerships

9. Give timely feedback, such as reviews every Friday or after every assignment in order to accelerate development

10. Conduct quarterly talent reviews that systematically analyze the health of the leadership pipeline, diversity, and succession—and create follow-up plans based on the outcome of these sessions

This list of practices is forward looking, but it is neither exhaustive nor universal. Different folks will apply different strokes, depending on their company’s strategic and economic foundation. Leadership models should be built from the outside in rather than imposed from above.

The list is also rooted in learning through doing and careful and orchestrated exposure to a range of new experiences rather than classic leadership training. You cannot teach many of the new skills in the classroom, but you can put future leaders outside of their comfort zone and force them to confront, in a controlled setting, the complexities of the modern world.

What’s important is thinking about leadership in a new way. The twenty-first century is still young, but it is getting late to address the leadership gap.