The half-life of industry leadership has declined precipitously in many sectors. To stay on top, companies must reinvent themselves and their strategies at a rate matching that of the external change that they face. Not only has the overall speed of change increased, but so too has the variety of strategic environments in which companies must function—across businesses and over time. Adaptive strategy has an important role to play here, but not the sole role. Rather, “adaptive” and “classical” are examples of strategic styles, and executives need to match their style of strategy to each environment in which they compete. In this article, we show how it can be done.

Matching Strategic Style to the Environment

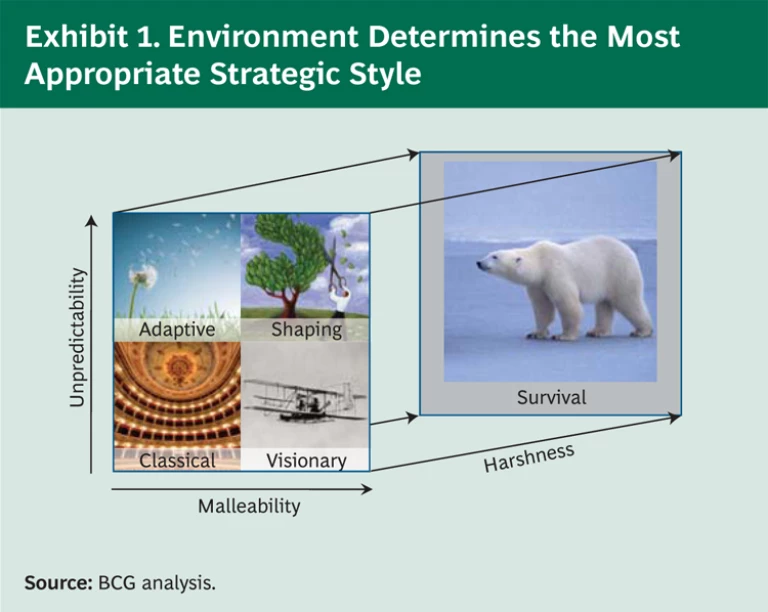

Deciding on the best strategy for a particular business begins with understanding the business environment along three dimensions:

- Predictability: the extent to which the future of the environment can be forecast, which depends on the degree of complexity and dynamic change

- Malleability: the extent to which the environment can be changed or shaped by the actions of companies individually or collectively

- Harshness: the extent to which an environment’s lack of resources—a result of economic or competitive conditions—constrains viability and growth

How a company assesses its environment along each of these dimensions will help determine the most appropriate strategic style. The first two dimensions—predictability and malleability—define a choice matrix of four very distinct strategic styles: classical, adaptive, shaping, and visionary, as illustrated in the exhibit below. The degree of harshness in the environment—a major concern for many companies today—adds a third dimension of choice and defines a fifth strategic style: survival.

Classical strategy—finding or building positions or leveraging unique resources—works best in a stable, predictable environment that is not easily altered. For example, a paper producer might be well served by a classical strategy if both the price of paper and the demand for paper are relatively predictable. A producer would analyze these factors to determine how best to position itself relative to its competitors in order to maximize profits.

When it is difficult to either predict the future or alter it, companies need an adaptive strategy to respond to whatever may happen. In contrast to classical strategies, adaptive strategies are characterized by an iterative learning process that consists of the following stages:

- Variation: addressing a changing environment through the creation of novelty

- Selection: choosing the most promising variations

- Amplification: scaling up and optimizing the selected variations and, where appropriate, hard-wiring them into the organization

- Modulation: fine-tuning the learning system in response to the changing environmental context and corporate goals

Retail is one of many sectors where adaptiveness is essential. Specialty retailers, for example, often find it difficult to predict demand for the many products in their portfolios, and must instead identify and quickly react to signals from customers. Tastes in fashions and brands can change quickly, and factors such as product availability, shelf location, and price add complexity that makes forecasting difficult. Retailers that employ adaptive strategies learn to test different product portfolios, identifying optimal patterns and then rapidly scaling the best models for their stores and product lines.

When the future is unpredictable but malleable by some players, such companies can employ a shaping strategy. Systems of companies often come together to pursue shaping strategies in the embryonic stages of a new industry or after a major disruption. For example, Internet software and services companies frequently leveraged shaping strategies in the early stages of the digital revolution by creating new communities, standards, and platforms that became the foundations for new markets and businesses.

A visionary strategy is called for when a company can envision an attractive future end state and also has the ability to realize it. Often leveraged by entrepreneurs, a visionary strategy is characterized by a “build it and they will come approach.” For example, some software companies operate by disrupting existing businesses with a new substitute—as innovative tax software disrupted the tax advisory and preparations industry or as drafting software changed how architects work.

When the environment is harsh, companies must focus on defensive moves, just as animals seek shelter and lower their metabolism in extreme conditions. All the strategies described above presume that the environment is relatively benign and that sufficient resources are available. However, this is not the case in many industries today—particularly in sectors such as financial services, oil and gas, automotive, and airlines. During recessions and downturns, when resources are scarce, a company must adopt a survival strategy that might focus on eliminating waste, boosting efficiency, mitigating risks, and divesting noncore assets.

Choosing the Appropriate Strategic Style

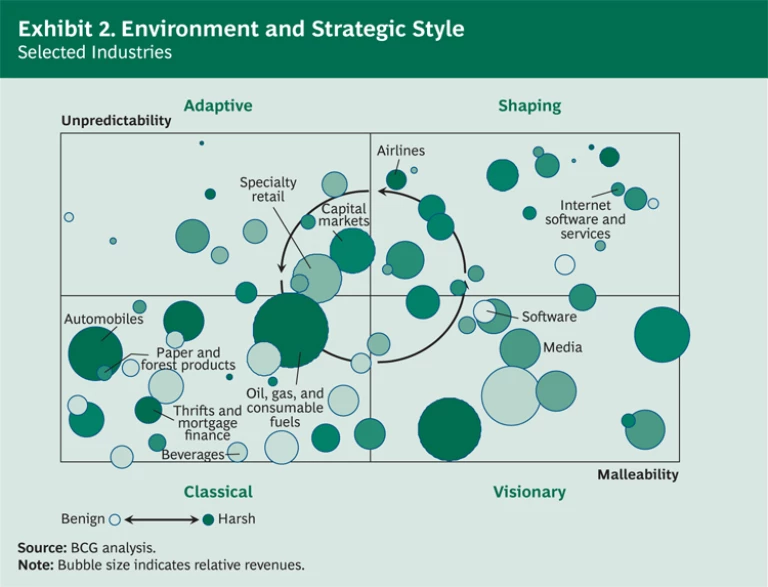

Companies must identify a style of strategy that is appropriate not only for their industry but for every region in which they operate, for every function, and for every stage of their own or their industry’s life cycle. For example, the exhibit below shows the extent to which industries are unpredictable, malleable, and benign or harsh and their appropriate strategic style (the labeled industries are those explicitly mentioned in this article).

Of course, this is not a rigid rule. Within a given industry, companies may choose different strategic styles according to differences in their business models.

Consider an industry that is highly concentrated, which makes it less malleable. Because a small company does not have the power to shape such an industry, it is better off pursuing an adaptive or a classical strategy. However, a large company might have the power to shape that industry and might be better off pursuing a shaping or a visionary strategy.

We can apply the same framework to geography. Many emerging markets are likely to be both unpredictable and malleable, making a shaping strategy most attractive. In contrast, developed countries are generally more predictable and less malleable, making a classical strategy more promising. For example, we estimate that the overall Chinese business environment is almost twice as malleable and unpredictable as that of the United States. Today, however, many developed countries are facing great unpredictability (in Europe, for instance), making a more adaptive approach best. And some countries are experiencing extremely harsh economic conditions, making survival strategies most appropriate.

Because some individual functions within companies differ in malleability and in their exposure to unpredictability, they too require different strategic styles. For instance, production is frequently characterized by low volatility (low unpredictability) and high fixed costs (low malleability), making it a candidate for classical planning approaches. Marketing is often more volatile and unpredictable, but it involves fewer fixed assets, which makes it very malleable. This frequently calls for a shaping strategy, especially under current turbulent economic and technological conditions. However, the same function may have different characteristics in different industries and thus would require different strategic styles.

Finally, we can match a company’s or an industry’s life-cycle stage to the most appropriate strategy. Companies (as well as industries) begin in a start-up phase, then grow into maturity, and finally begin to decline. At this point, some companies continue to their demise, while others are able to bring about a renaissance and restart the cycle.

The degree of malleability and unpredictability differs across the stages of a life cycle. For example, in the startup phase, the environment is usually malleable, which calls for either a shaping or a visionary strategy. This is now the case, for example, in the clean-technology industries. In the growth and maturity phases of a life cycle, the environment is less malleable, and adaptive or classical strategy styles are best. For example, the beverage industry is a growing but relatively mature industry where classical strategy may be optimal. In the decline phase of a life cycle, the environment eventually becomes more malleable, generating opportunities for either a shaping or a visionary strategy. For example, the media industry is now ripe for change and reshaping strategies.

Companies must de-average their strategies in this way across their portfolios and over time, so that a single company may deploy different strategic styles for its various regions and functions. In its emerging-markets division, for instance, it may pursue an adaptive or a shaping strategy. In its developed markets, it may have a portfolio of styles that align with specific sector conditions. Therefore, companies must make sure that their planning and managerial processes allow both for de-averaging strategic styles and for modulating them over time as the environment changes. Companies can of course de-average their styles by physically separating teams running functions, regions, or business units that demand different strategic styles. As the frequency of change and the need for strategic adaptability increase, however, each organizational unit may need to be capable of housing multiple or changing styles. This can be achieved by a variety of means, such as de-averaging and modulating the performance contract with each part of the organization; building flexible planning processes and flexible, modular organizations; and employing people with diverse cognitive styles and backgrounds.

From Theory to Practice

The need to match strategy to the environmental context is not new. However, the urgency to do so has intensified as the variety and rate of change of business environments have increased. Modulating strategic styles across the portfolio and over time has implications for the whole organization and its leadership. To test how well your strategic style matches your environment, ask yourself the following questions:

- What conditions does each part of the business face in terms of unpredictability, malleability, and harshness?

- What implicit styles of strategy are we are applying to each part of the business and how appropriate are they?

- How should we structure our planning processes and organization to enable the appropriate choice and diversity of strategic styles across our portfolio?

- What are the cultural and leadership implications of maintaining this portfolio of strategic stances?

Michael Porter said in an interview in Fast Company in 2001, “Strategy must have continuity. It can’t be constantly reinvented.” However, as the speed of change in many business environments increases, so too must the speed at which we reinvent strategies. Business leaders today cannot always take comfort in applying stable, continuing strategies when their environment is anything but stable, or in applying one style of strategy over time and across businesses and regions. Instead, they must learn to match their strategic style to their environment, apply multiple styles as appropriate, and evolve their strategies at the appropriate rate.