Working in collaboration with the Grocery Manufacturers of America (GMA) and its membership, The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) conducted extensive benchmarking on topics related to effective supply-chain management. The resulting report, GMA Supply-Chain Benchmarking 2012: Unlocking the Hidden Value of Complexity Management and Collaboration, is based on a survey of 51 CPG manufacturers in the U.S., supplemented by interviews with 65 supply-chain executives. It also incorporates data that BCG gathered by polling 116 attendees at the February 2013 Supply Chain Conference, jointly hosted by the GMA and the FMI, including retailer views. Furthermore, it draws on BCG’s experience working with many of the leading CPG manufacturers and retailers in the U.S.

Better complexity management offers the biggest opportunity for CPG manufacturers to unlock additional value. Across the industry, $16 billion to $28 billion in profits are being squandered through unnecessary complexity. But to release this value, companies need to look beyond SKUs and approach the issue from a more systematic, companywide perspective. However, better complexity management is only one way to release substantial value. There are also significant opportunities through greater collaboration.

Although variety can add value by providing consumers with greater choice, virtually all companies we talked to recognized that they have reached a point where the cost of complexity often outweighs the benefits to consumers. For example, in one segment (French fries), one company had more than 800 SKUs and more than 100 unique cut specifications. Similar complexity can be found in nearly every consumer-goods segment, spanning ambient, refrigerated, and frozen products.

Too many companies believe that successfully managing complexity is simply a question of reducing supply chain costs, traditionally done by cutting the low-selling products that make up the SKU “tail.” But SKUs are only the tip of the complexity iceberg. Effects of complexity ripple throughout the organization, affecting the length of production runs in manufacturing, the proliferation of different channel and customer requirements in sales, and the number of suppliers that the procurement department manages, for example. Instead of looking just at cutting SKUs, the supply chain needs to work in a systematic, integrated manner with every facet of the business across the value chain—from manufacturing to sales and marketing to procurement—to identify and remove costly complexity and to deliver and enable smart complexity that drives consumer value and sales.

Smart complexity involves focusing on products that better serve specific consumer segments or are better suited to a particular channel, for example. Complexity needs to be viewed through a market lens, not a pure cost lens. What is visibly different and valuable to the consumer, and does that consumer benefit outweigh the additional cost of complexity?

Massive Gains—and Losses—Related to Complexity Management Capabilities

The potential gains from better complexity management are huge. According to BCG’s experience, the CPG industry could increase its profit margins by 3 to 5 percent and boost its sales by up to 5 percent with more-effective complexity management, particularly by focusing on the bestsellers, reducing “shelf clutter,” and allowing innovation to shine.

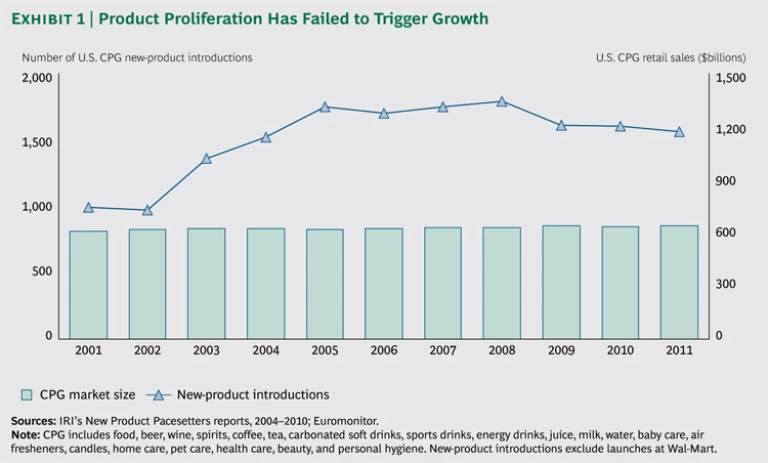

Conversely, in general there is little to be gained by increasing complexity. Complexity increased dramatically during the 2001–2011 period without any commensurate rise in sales for the industry. (See Exhibit 1.) However, some companies may have benefited by offering more variety and managing complexity well.

There is a significant amount to be lost through additional complexity. These costs are felt not just at the level of the SKU but throughout the business. Companywide costs of complexity include increased manufacturing downtime, working capital being tied up in excess inventory, and challenges across procurement, warehousing, and forecasting. These challenges can be further magnified by multifaceted sales and marketing positionings that can confuse consumers.

The Need to Turn Strategic Intent into Systematic Action

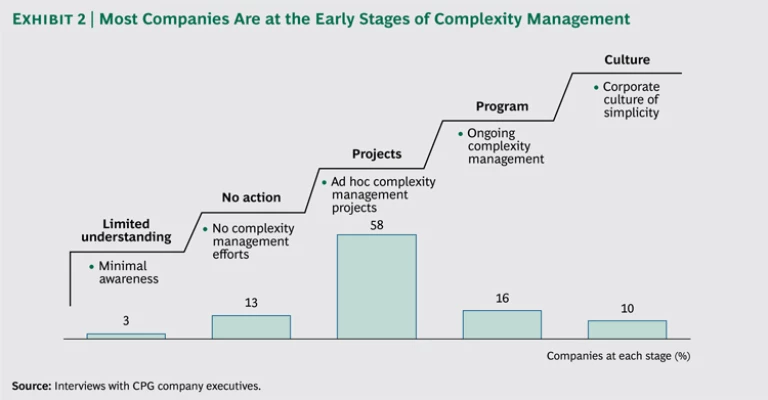

Manufacturers cite various hurdles to managing complexity, from difficulties in measuring the collective impact of incremental complexity to the challenges of securing companywide focus on the issue in large, complex organizations. But the most fundamental problem is turning strategic intent into concrete, systematic action. Despite the fact that nine out of ten companies claim that complexity management is a strategic problem—or “a significant pain point,” as one interviewee called it—only 26 percent are systematically addressing the issue. (And most address it through complexity reduction.) For example, only 16 percent of the companies whose executives we interviewed have ongoing complexity initiatives and just 10 percent are working to instill a culture of simplicity. (See Exhibit 2.)

Most companies are still at the starting point of complexity management, typically undertaking ad hoc projects focused on SKU rationalization. But one of the problems with narrowly focusing on rationalizing or cutting the tail of a SKU portfolio is that SKUs account for only a small proportion of complexity costs. To make real headway, you need to look “under the hood” of all SKUs. “You need to get under the skin to the ingredients and packaging to get real savings,” said a senior executive of a personal-care-product company.

Experience has also shown that complexity has a tendency to creep back into the portfolio. “We cut our SKUs by 60 percent, but churn hasn’t changed. So we will have proliferation again,” admitted an executive of a household products company. Another interviewee said, “We tend to be better at pruning than managing and preventing complexity.”

The Challenge of Internal and External Alignment

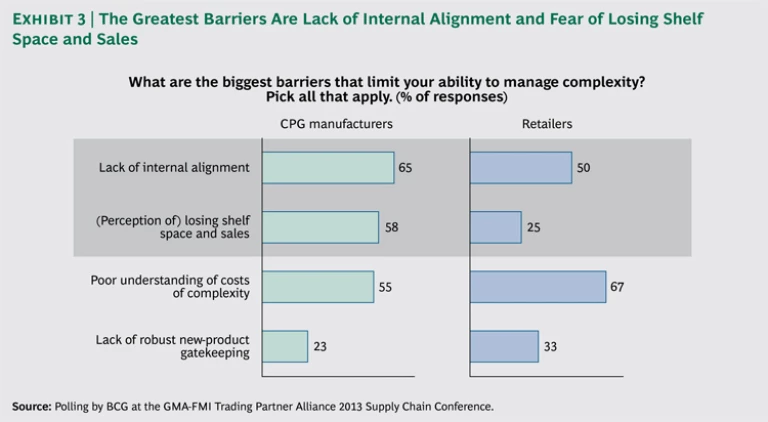

The barriers to abandoning a narrow focus on SKUs in favor of a more integrated, companywide approach to complexity management vary for manufacturers and retailers and by company size. One of the major obstacles that most businesses mentioned was the lack of internal alignment. Specifically, businesses have difficulty in establishing a shared, companywide focus on complexity management, spanning all the relevant functions, from R&D to sales and marketing. In our conference session, nearly two-thirds of manufacturers and half of retailers cited this problem as a major issue. (See Exhibit 3.)

Part of the difficulty is resolving ostensibly competing objectives: the supply chain’s need to reduce complexity and sales and marketing’s need to meet customers’ requirements. “Sales is worried that some customers may be offended if we discontinue products,” said one executive. Another commented, “Marketing says we need all the SKUs to meet consumer demand.” Other obstacles to internal alignment include lack of cross-functional cooperation, such as forums in which to address companywide complexity issues. Difficulties in quantifying the costs of complexity can also prevent discussions from even starting.

External alignment with trading partners is also a major issue, especially for manufacturers. Nearly 60 percent of the manufacturers studied expressed fears that complexity reduction would result in less shelf space for their products, compared with just 25 percent of retailers concerned about losing sales through greater simplicity. “Sales really wants to hold on to their shelf space,” claimed a supply chain executive.

Key Enablers for Managing Complexity to Unlock Value

Despite the hurdles, some companies are making significant progress in managing complexity to add value. These companies are focusing on four key enablers.

Treat complexity management as a holistic, cross-functional exercise, with top-level support. The companywide nature of complexity requires a systematic, cross-functional approach, from manufacturing and procurement through sales and marketing. Chocolate manufacturer Ferrero U.S.A. has achieved this by turning simplicity into a companywide value, enabling the business to keep the number of its SKUs steady at approximately 140 units over the 2007–2012 period. As a relatively small organization in the U.S., the company has been able to ensure a strong, close dialogue between the supply chain and sales and marketing. “It’s important to have buy-in from sales and marketing that whatever we do is right for the business,” said one executive. Above all, there is a shared vision of simplicity as a key competitive strength throughout the company. “If there’s a request for an addition in one area, we typically remove an item in another area.”

Quantify the costs of complexity across the value chain. To find the optimum balance between the value of variety and the costs of complexity, companies need to understand the full economics on both the demand and the supply side, underlining the importance of a cross-functional approach. On the supply side, what are the drivers of complexity and their relative costs for each SKU?

One manufacturer has reaped the benefits of an in-depth understanding of the value and costs of complexity. Having developed the ability to analyze value and costs—related, for example, to a retailer’s request for a customized pallet—it can determine the best way to respond. In this example, the company would go ahead with the initiative only if the customer is willing to absorb the cost. “If they are willing to pay for it, then it’s worth it,” said a representative of this company. However, the company adds a note of caution: “It sounds simple but it’s not—you need to have the infrastructure in place for activity-based costing.”

Another advantage of pinpointing the drivers and costs of complexity is that doing so enables businesses to identify ways to reduce the costs of “good” complexity. Companies take different routes to cut these costs. For instance, one manufacturer uses a standardized, modular platform for its point-of-sale (POS) displays for multiple products and differentiates each with a different banner. “It saves times and removes complexity,” generating “six-digit savings” for the company.

Complexity scorecards should be used to assess the relative value and costs of each SKU, and “tollgates” should be established to determine whether new SKUs, subplatforms, and product-line updates deliver profitable variety.

Focus on market-driven profit maximization, not just cost reductions. A narrow focus on cost-driven SKU rationalization not only overlooks broader gains, including opportunities to increase sales, but also risks cutting profitable parts of the tail. Instead, complexity should be managed through the lens of consumers’ needs, with an eye firmly trained on variety that adds value and sales growth as well as unnecessary complexity that raises costs.

One household- and lifestyle-product manufacturer has mastered this art with impressive results. For example, the company significantly reduced packaging variety, having discovered that the previous variety did not add much value to consumers. “Product harmonization helped grow the business and got a ton of the complexity costs out,” explained a senior supply-chain executive.

Institutionalize complexity management as a systematic, ongoing activity. Complexity management should be not a one-off exercise but an integral part of a company’s strategy and day-to-day operations. Unilever institutionalized complexity management by initially creating a high-level, dedicated task force to assess complexity across the business and establish the systems to tackle it. It was important that the analysis started at the shelf, taking into account consumer insights. From there, the findings were worked into all processes, proceeding backwards through the organization. Once the program was proved, it was embedded in each of the categories, with brand managers held accountable, through annual reviews, for managing complexity.

Unilever has further embedded complexity management into its business by making the supply chain and brand teams jointly responsible for the P&L. “It’s easy to get supply chain at the table; every brand person wants to put his thumbprint on a product, so you have to figure out what’s in it for marketing to make it work,” said one of the company’s supply-chain managers. As with many businesses that successfully manage complexity, top-level support has been critical. “Endorsement from the president of Unilever is our largest success factor.”

Key Questions for Supply Chain Executives

To effectively address the challenges of managing complexity, supply chain executives need to answer the following questions:

- What level of complexity do you strategically want to support?

- Who owns complexity management within your organization?

- Which product varieties and design elements drive consumer choice?

- What are the underlying drivers of complexity, beyond SKUs, and are costs adequately reflected in product pricing?

- Are products phased out as new products are introduced?