Companies that have disrupted technology markets have been re-warded with exceptionally high valuation-to-revenue ratios. Incumbent technology companies, recognizing the imperative to emulate these disrupters, have transitioned from their legacy business models to new and disruptive growth models. Software companies that have made the transition from a licensing to a subscription model—or have demonstrated that they are in the process of doing so—have achieved valuations as high as five times revenues.

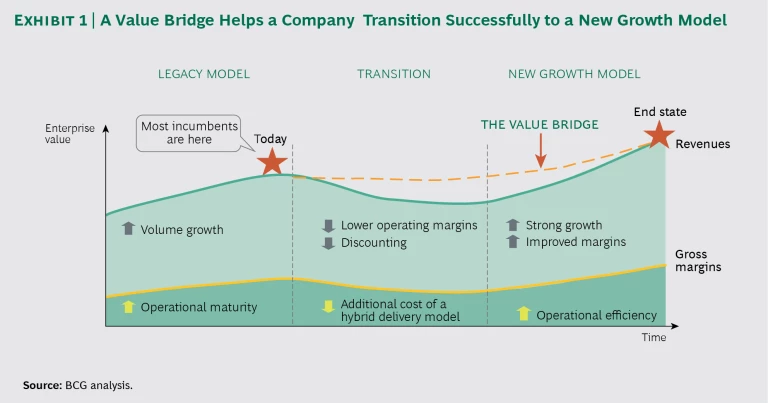

However, transitioning to a new growth model is inherently difficult for companies that have already reached a high level of operational maturity and enjoy high revenues and margins. Implementing a new model requires them to radically alter their engineering, marketing, and selling capabilities, and, almost inevitably, such transitions lead to a period of lower revenues and gross margins. If investors lack confidence that a company will return to or exceed its previous performance peak, its enterprise value declines and, in the worst case, never recovers.

A successful transition entails building a “value bridge” that avoids substantial dips in enterprise value and leads to the future high-growth state. Building such a bridge requires a five-part approach that not only sends strong signals that the company is committed to the new growth model but also increases investors’ confidence that the company can deliver on its promise. In BCG’s experience, some companies that have succeeded in this approach have doubled their value within a year.

Valuations Can Decline During Transitions

Until recently, incumbent technology companies had been well served by their legacy business models. In many cases, volume growth elevated revenues while operational maturity resulted in high gross margins. In return, investors rewarded these companies with high valuations.

During the past decade, however, several new growth areas have emerged in the technology sector. Startups have ushered in an era of disruption, bringing, for example, the Internet of Things, as-a-service delivery models, and big data. Many disruptors that were growing rapidly have achieved very high market valuations. At the same time, incumbents in such businesses as software, networking, and semiconductors have watched growth slow and valuations decline. Despite the clear need to adapt, many companies that have tried to adopt new models still trail behind the disrupters and have failed to realize their value potential.

To succeed, companies must first come to terms with a harsh reality: transitioning to a new growth model is inherently difficult and, at least in the short term, can actually drive down revenues and gross margins. Among the factors that affect performance are lower operating margins, the need to discount new offerings, and the additional cost of having to operate with several business models concurrently. Investors are inclined to punish a company for such performance problems by reducing its valuation—unless the company reassures them that it can weather the transition period. By building a value bridge, a company can convince investors that it will succeed in reversing the initial downward trend and will capture the benefits of strong growth, higher margins, and greater operational efficiency. (See Exhibit 1.)

Building a Value Bridge

On the basis of our experience supporting companies through the transition to a new growth model, BCG has developed a five-part approach to building a value bridge.

Generate Substantial Value from the New Model

With only a few credible signs that indicate that a new model is generating value, a company can significantly bolster investor confidence in a transition. To satisfy investors, value from the new growth model—through organic growth or transformational M&A—must represent 10% to 20% of the company’s total value. If the company’s commitment and momentum are convincing, then showing investors that the new model generates at least 5% of the company’s total revenues can serve as a credible demonstration of value.

In assessing the potential for value creation, it is critical to estimate—on the basis of successful transitions—“trapped value,” the difference between the transitioning company’s current market capitalization and the value achievable. BCG’s Smart Multiple methodology uses proprietary modeling to empirically identify the drivers of a valuation multiple. The modeling is supported by investor interviews and a review of sell-side reports that show how investors view the prospects of companies in a particular industry. This methodology typically explains 80% to 90% of the variation in multiples, and it provides critical insights for companies seeking to improve their value creation performance. To estimate the value creation potential of each of a company’s businesses, BCG uses a metric we call internal total shareholder return (iTSR). This metric is a direct proxy for how a business is likely to create value and contribute to the overall share price and TSR. We use a financial plan and forecast of valuation drivers to simulate future iTSR.

Manage Pricing Levers to Limit Price Erosion

Although price erosion is common during the transition to a new growth model, a company can take steps to limit it. New growth areas typically require simplified pricing models that are based on usage and value. Rather than trying to extract the maximum value from new offerings right away, the company should focus on increasing its share of wallet by upselling over time. The elimination of midtier offers and the increased use of bundling can help drive upselling. Discounting should be adjusted to reflect the long-term economics of the new model. (See “The One Ratio Every Subscription Business Needs to Know: Using LTV/CAC to Guide Investments and Operations,” BCG article, February 2017.)

Make Operational Changes to Unlock Growth

To unlock growth, a company must implement operational changes across its organizational units:

- Sales and Marketing. For the new growth model, the company should invest significantly in efforts that include a new go-to-market plan. The most critical aspects of such a plan involve increasing the use of inside sales, engaging with new channel partners or requiring legacy channel partners to upgrade their capabilities, training the sales force on incremental selling (“land and expand”), implementing new sales incentives, and focusing on different key customers and decision makers (for example, the business unit rather than the IT function).

- The Partner Ecosystem. The partner ecosystem must change dramatically as well. The company needs to recruit new partners with capabilities, reach, and business models that are consistent with its new growth areas. For example, Salesforce.com developed an ecosystem of systems integrators to help customers integrate its cloud products into their IT stack. The existing partner ecosystem had been focusing on the lucrative systems integration work for the company’s large legacy business and thus had no incentive to devote time and money to the emerging cloud business.

- Product Engineering. Most engineering teams must undergo a major cultural change. Development and operations engineers need to adopt a set of practices known as DevOps, through which they work together during an application’s life cycle to achieve greater speed and higher quality. Furthermore, they must be able to apply continuous product usage data and feedback, and they should have the agility to develop incremental releases. A flatter organization structure and the automation of testing and quality assurance are essential for achieving these objectives.

- Operations and Support. At most technology companies, the end-user support function has been a reactive, back-office operation. To support new technology growth models, this function must become a revenue-generating “customer success” function that reaches out to customers, offering guidance and advice. The function’s staff can apply data-driven insights about a customer’s business needs to offer upgrades and new solutions. Because this function provides predictive outreach, as well as support, it becomes a critical enabler of a land-and-expand strategy.

- Infrastructure and Enablers. Companies must strive to become agile from end to end. For example, because they need to continually engage with customers, they must establish systems that provide a comprehensive view of each customer’s business with the company, simultaneously ensuring customer privacy.

Target GARP Investors

For large companies transitioning to a new growth model, the natural investor base comprises growth-at-a-reasonable-price (GARP) investors. GARP investors look for companies with top-line growth lower than 15%, which matches the growth expectation for a large company undergoing a transition. GARP investors are, therefore, willing to pay a premium for an equity position in such a company. During the transition, they expect a 2% to 3% dividend yield and, in many cases, a commitment to growth of future dividends, to compensate for the slow growth of earnings per share (EPS), as well as a price-to-earnings ratio that is higher than the S&P 500’s average of 18. For companies with top-line growth exceeding 15% (likely smaller companies), growth investors should be the target investor base.

Recognizing the need to attract GARP investors, leading technology companies increase dividends to support their stock price during business model transitions. Prior to 2008, dividends were not a significant factor in the valuation of technology companies.

However, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, many technology companies abandoned the perception that dividends indicate capitulation to a slow-growth future. Companies with annual EPS growth expectations lower than 10% started paying higher dividends, which led large mutual funds that require dividends to expand their positions in these companies. And because a premium valuation can be justified if the dividend growth rate exceeds the cost of capital, enterprise value also increased.

Convey a Clear Message to Investors

It is essential to emphasize management’s commitment to the new growth model by announcing a clear strategy and product roadmap. Communications with investors should set out all the strategic levers that the company plans to use in the transition, including M&A, organic growth, and product development.

If the company plans to pursue M&A, it must make a convincing argument that growth by acquisition is essential to enhance revenues and margins. To support their cloud transitions, leading tech companies have made extensive use of M&A over the course of several years: Microsoft acquired LinkedIn; Oracle, Netsuite and Ravello Systems; and IBM, SoftLayer Technologies and Blue Box.

It is especially important to manage M&A announcements effectively. The CEOs of both the acquirer and the acquisition should participate in the announcement, answering investors’ questions. Companies should invite representatives of the leading mutual funds, including growth and GARP portfolio managers within large fund families. Although sell-side analysts are still important and should be included, their influence on valuations has diminished.

The company should inform investors about the metrics it uses to gauge success in the new growth segment. For each metric, the company must state specific targets and present its plan for achieving them. To enhance transparency, it should describe each metric and its key components, such as revenues, gross margins, and R&D investments.

The Value Bridge in Operation

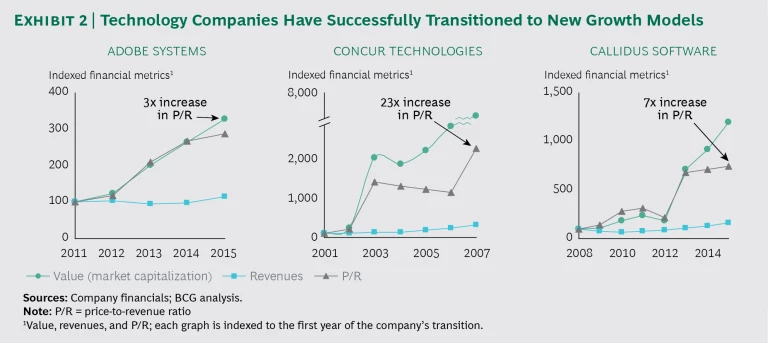

We studied three software companies—Adobe Systems, Concur Technologies, and Callidus Software—that stand out for their ability to raise valuation multiples by successfully managing a transition. (See Exhibit 2.) Each of these companies has transitioned from a licensing to a software-as-a-service (SaaS) model.

Prior to 2013, Adobe Systems’ revenues were generated almost exclusively by one-time sales of perpetual licenses. In 2012, the company shifted its core creative software suite to a subscription-based SaaS model. Initial declines in revenues and EPS were counteracted by strong growth in the subscription business. In 2015, Adobe generated 74% of its revenues from subscriptions, compared with just 11% in 2011.

Despite the initial revenue decline, Adobe’s value started to rise because the company had reassured investors that it was on track to succeed. The company had identified and targeted the top 20 GARP portfolio managers as part of its communications plan. Adobe had accurately modeled the expected financial impact of transitioning to SaaS and described it to investor and sell-side analysts, with a buffer to help ensure that it would beat expectations. Furthermore, the company publicized new metrics and limited new development activities to SaaS offerings. Investors rewarded Adobe for these efforts: the company’s market capitalization more than tripled from 2011 through 2015.

Adobe followed in the footsteps of Concur Technologies, a travel and expense management software company that had shifted its entire business to a SaaS model during the technology downturn at the beginning of the century. At the time, Concur’s on-premises business model was generating $34 million in annual revenues. The success of the transition, which entailed essentially starting a new business, required a significant amount of time and effort.

The hard work paid off. Within seven years, Concur was more than ten times the size of its chief competitor. By 2012, revenues had climbed to $440 million. Because executives were able to keep the promises made to investors, value skyrocketed: Concur shares outperformed the Nasdaq by a factor of 30 from 2000 through 2012, while competitors underperformed. In 2014, SAP acquired the company, paying roughly 12 times its price-to-revenue ratio—$8.3 billion.

In 2008, Callidus Software, a developer of incentive management applications, began the transition from a license-based model to SaaS. The company pursued the transition largely through M&A, acquiring eight companies over a two-year period. Although profitability was volatile during the transition, revenues eventually started to rise and value shot up.

In year five of the transition, annual revenue growth reached approximately 18%, after having declined by 24% during year one. Over the same period, Callidus’s valuation multiple increased fourfold.

Key Issues to Consider

In assessing whether or not it is prepared to build a value bridge, a technology company should answer a number of questions:

- What potential upside—in terms of revenues, margins, and free cash flow—can we expect from the new growth model? How long will it take to generate a substantial share of our total value from the new model?

- To what extent will revenues and value decrease during the transition? How can we minimize the declines?

- Which pricing levers should we use to minimize price erosion and maximize the opportunities for upselling over time?

- What operational and product changes are needed? To what extent should we use M&A to acquire new operational and product development capabilities?

- Have we identified the investors that are willing to pay the most for an equity position in our company and are we targeting them effectively?

- What is the best way to communicate a credible transition roadmap to investors? How will we deliver on our promises?

In many cases, companies find that the answers to these questions point to a need for external support in building a value bridge. The challenges are significant, but companies that succeed will be rewarded with a thriving business and a high valuation multiple.