Shining today, gone tomorrow? For every Apple, there is an Atari, for every Fuji a Polaroid, and for every Netflix a Blockbuster. It’s harder to stay on top than to get there. How can you avoid the seemingly inevitable and become an “evergreen” corporation?

In past research, we showed that companies die sooner than ever before: one in three public companies overall and one in six large companies will not survive the next five years. (See “Die Another Day: What Leaders Can Do About the Shrinking Life Expectancy of Corporations,” BCG Perspectives, July 2015.) We now reveal that despite this threat to their longevity, companies are more focused than ever on the short term. This failure to take the long view is often a result of past success—a phenomenon we call the “success trap.”

The biggest threat to the survival of large companies may therefore come not from Silicon Valley or China, but from their own lack of strategic renewal. The good news is that premature demise is far from inevitable. Leaders hold their companies’ fates in their hands. We offer five action imperatives to help leaders turn their companies into sustainably growing, value-creating, evergreen corporations.

Large, Established Companies Are Increasingly Vulnerable

In the 1960s, BCG’s founder, Bruce Henderson, said that bigness is a big idea. High relative market share yields lower costs, which generate more cash to fund growth, creating a virtuous cycle of sustained competitive advantage. But size no longer means what it used to: today, only 7% of companies that are market share leaders are also profit leaders in their industries—down from 25% in the 1960s. Scale is thus increasingly an indication of past success, not a predictor of future performance.

Scale can also deceive: it initially serves as a buffer against external pressures, making large, established companies generally more resilient than smaller, younger ones. This resilience, however, does not compensate indefinitely for insufficient investments in future growth options. Size frequently leads to inertia, slowly driving up mortality even among the largest companies.

Embracing the Dynamism and Diversity of Business Environments

Large companies cannot afford to be complacent. Markets are more dynamic than in the past, requiring companies to innovate and self-disrupt more frequently and decisively. Market conditions are also more diverse than ever before, so companies must

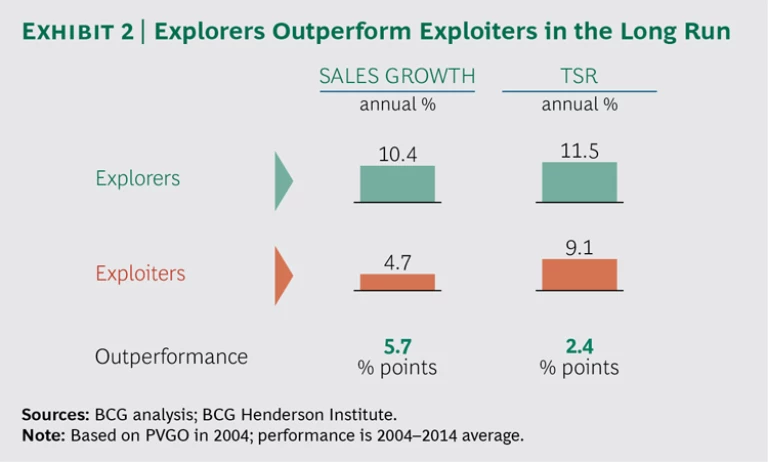

Ambidexterity also means balance—exploiting existing business options while exploring new ones, running and reinventing the company at the same time. Exploratory activities include searching for, nurturing, and scaling growth opportunities, whereas exploitative activities involve refining existing recipes for success. Big corporations with a legacy of success in their core businesses often tend toward overexploitation. They overestimate the longevity of their products and business models and underinvest in building new ones. Ironically, when results begin to fade, these companies often respond by setting off a vicious cycle of cost reductions and share buybacks. Such interventions tend to further marginalize exploratory activities and lead the company onto an inexorable path toward the success trap.

What is this trap, and why do companies fall into it?

Meet the Success Trap

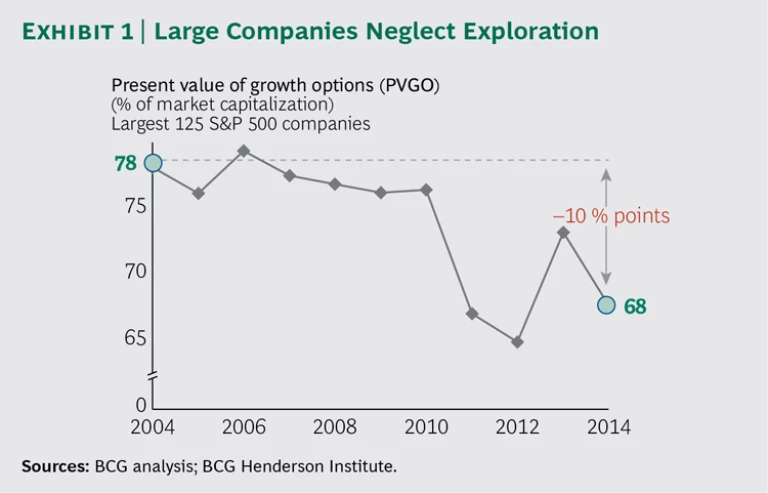

To answer those questions, we measured the degree of exploration in the S&P 500 by calculating the

A large portion of the decline in exploration is accounted for by companies that have been S&P 500 members for a long time. Those companies are often strategically and organizationally locked in to their historically successful business models. As a result, they are less exploratory—by close to 20 percentage points—than their younger peers. These established companies have also seen the most dramatic reductions in their exploratory activity. As a result, the trend away from exploration toward exploitation is

To be clear, the turn toward exploitation may not immediately affect investors, because companies can maintain earnings and shareholder returns in the short term by cutting costs, increasing dividends, and pursuing share buybacks. Such companies become “value stocks”—essentially bonds, in the eyes of investors—and are stuck on a path of low growth and continual efficiency improvements, which are hard to sustain. This path leads to a trap of overexploitation, the success trap.

Our research shows that companies in this trap—

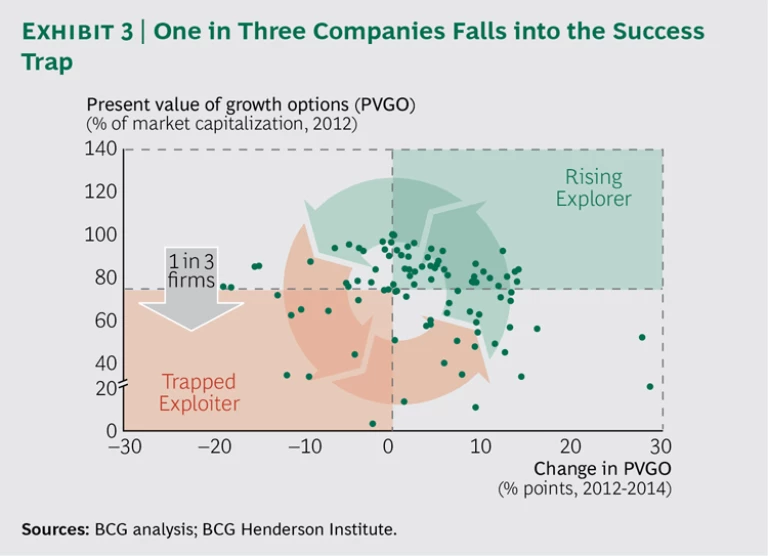

Fortunately, not all companies fall into the success trap. Young companies have to balance exploration (developing winning products and business models) and exploitation (generating cash to support growth) in order to survive and thrive. Some companies maintain this dual discipline even when they attain scale. Amazon and Google, for example, are able to sustain their exploratory drive while focusing on operational efficiency and commercial excellence.

Only one in ten companies manages to follow this example. The remaining nine do not stay in the top right quadrant over a ten-year period. (See Exhibit 3.) These companies, often formerly successful, follow a predictable path toward overexploitation—overoptimizing and overrelying on their past recipes for success. Over a five-year period, three of those nine companies keep following the path and end up falling into the success trap.

Paradoxically, doing so often seems like the right choice. Fine-tuning the current, successful model provides higher immediate rewards at low risk for the company and its managers and shareholders. But this choice comes at the cost of lower growth, which jeopardizes the company’s future. Fast-forward a few years, and lower growth means fewer interactions with new, demanding customer groups and less inspiration to innovate. Eventually, the company is likely to be out of touch with changing market requirements. At that point, it is often too late to course-correct. The company has fallen into the success trap. Our research shows that it is surprisingly difficult to escape this trap. More than two in three companies fail to get back onto the path of exploration within five years.

Five Imperatives for Action

Big companies need to avoid the success trap if they aspire to become evergreen corporations. Executives can steer their companies away from the trap by executing the right approaches to strategy for each part of the business, cultivating the right capabilities, organizing appropriately, and leading in the right manner.

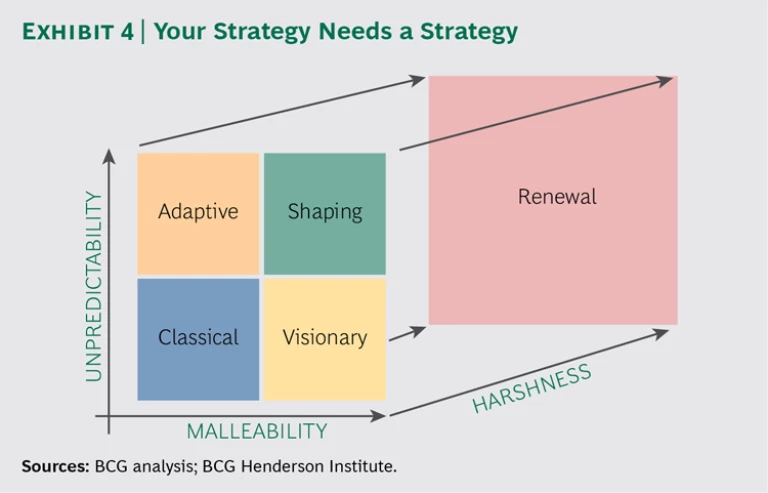

1. Adopt the right approach to strategy and execution in each part of the business. Your strategy needs a strategy. In other words, leaders need to extend their repertoire beyond analysis, prediction, and planning. This classical approach to strategy may work when the environment is highly predictable, but less predictable, more malleable, or even harsh conditions call for other approaches. (See Exhibit 4.) Developing these new approaches is easier said than done. In order to execute effective strategies for such business environments, companies need to build new adaptive and shaping capabilities.

2. Cultivate an adaptive capability. Unpredictable environments require rapid adjustment to changing market conditions. Young companies understand this intuitively, moving through “vary, select, and amplify” cycles until they find a successful model to scale. To some extent, big companies need to unlearn their predisposition toward planning, prediction, and precision and relearn how to pursue disciplined experimentation. Tata Consultancy Services, an IT service provider, is an example of a large company that executes such an adaptive approach to strategy by encouraging experimentation.

3. Cultivate a shaping capability. Scale may not guarantee sustained success, but it can help a company shape its environment by deploying influence in a wider ecosystem. Apple, for example, forged its initial groundbreaking deals with the five major record labels in 2002 thanks to its large user base and the music industry’s trust in Apple’s technology competence. Leaders of large companies need to recognize their potential influence and use it to shape business ecosystems.

4. Cultivate ambidexterity. Choosing the right approaches to strategy and execution is not enough. Big companies need to continually adjust the balance of strategic approaches across their businesses in order to simultaneously run and reinvent the company. Metrics and incentives for continual exploration can help. 3M, for example, pioneered the New Product Vitality Index (NPVI), a metric that tracks the share of sales from products that didn’t exist five years ago. But companies need to go beyond introducing one new metric. Corporate centers should consider de-averaging performance contracts across business units and employing differentiated steering models. Pfizer provides a case in point. The pharma company takes different strategic approaches and cultivates different cultures in its global innovative pharma and global established pharma units.

Such variety can be hard to contain under the same roof. Hence, companies need to adapt the structure of the organization to safeguard exploration and maintain ambidexterity. An example is Google’s recent reorganization into Alphabet, which separated the more mature search business from exploratory units such as Google X. A more radical approach is to split the company, as eBay did with the recent spin-off of its PayPal business.

In more dynamic environments, businesses should consider self-organization. Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce giant, employs self-steering teams to continually match its business to market conditions through co-creation sessions with customers. Through this process, the company has morphed itself from an export marketplace into an evolving portfolio of e-commerce-related businesses—and has solidified its position as China’s most valuable tech company.

5. Animate the resulting collage of strategy approaches. A company’s journey to become an ambidextrous organization starts and ends with its leaders. To animate the collage of strategy approaches and overcome the organization’s natural tendency to rely on familiar, comfortable, or formerly successful recipes, leaders must reconceive their role. In particular, they need to cultivate a state of artful disequilibrium throughout the organization. To amplify their efforts, they must build a leadership team that is committed to the health of the overall portfolio, not to the championing and protection of individual businesses. Above all, leaders need their teams to embrace the contradictory requirements of exploration and exploitation. As Peter Hancock, the CEO of AIG, told us, “I always hear, ‘You’re giving me mixed messages.’ I say, ‘You’re a leader—you’re paid to deliver mixed messages!’”

The quest to become an evergreen corporation is ever elusive. We do not claim to have found a definitive answer. Still, companies that take these five imperatives to heart are more likely to stay on top, avoiding the success trap and positioning themselves to shape their future.