One of the greatest challenges for pharmaceutical executives has always been deciding how to allocate commercial resources throughout the life cycle of individual brands in order to connect with medical professionals and maximize sales and profitability. (See Brand Renaissance: Five Ways to Win Commercially in Pharmaceutical Markets, BCG Focus, December 2011.) That challenge is more acute now than ever before: virtually every therapeutic area has grown increasingly competitive, and medical professionals have an ever-greater need for the information that can help them make better informed clinical decisions. Despite this, we have found that pharmaceutical executives, for the most part, are not seizing the opportunity effectively to build key bridges with medical professionals, and neither the pharma nor the physician side is satisfied.

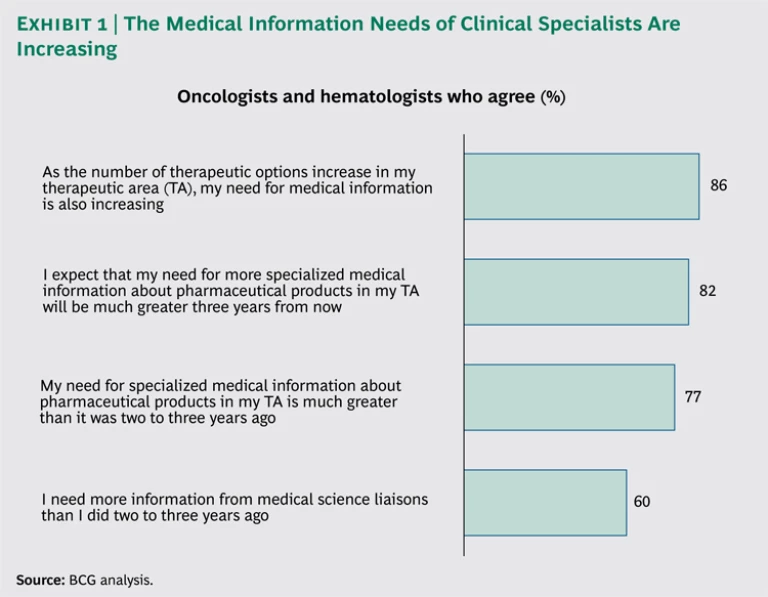

The function that historically builds this bridge for pharma companies is the medical affairs team. (The role of medical affairs varies somewhat across the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, but we focus this discussion on its role in sharing medical information with health care professionals.) The job of medical affairs has become increasingly important as physicians’ medical-information needs have grown and become more complex. (See Exhibit 1.) In our experience, virtually every pharma company is struggling to determine how best to respond to the changing environment and invest in and adapt the medical affairs model in order to become both a differentiator and a source of sustainable competitive advantage.

Rethinking Medical Affairs

We have identified three critical success factors for pharma companies that strive to differentiate their medical affairs offering, as well as to support medical professionals effectively in advancing patient care:

- Investing disproportionate resources in products that generate the greatest demand for medical information

- Investing the time to understand medical professionals’ most pressing information needs for a specific disease state or therapeutic area—and developing an offering that meets these needs

- Aligning the medical affairs organization with the mission of earning the trust of medical professionals

Investing Resources in the Right Places

Pharma companies typically invest in commercial activities on the basis of a product’s revenue potential, competitive context, and life-cycle stage. Although the precise formula can vary, the principles for resource investment are clear. However, applying that same approach to medical affairs will not deliver the best results.

In order to determine the appropriate allocation of resources to medical affairs for a particular product, companies must focus on answering two core questions:

- How much information do medical professionals need? In general, the products that generate the greatest need for information have a novel attribute (for example, a new “mechanism of action” or a biochemical interaction produced by a drug), employ a more complex clinical protocol, and are used by specialists who have access to an increasing array of products for treating different types of patients. In addition, doctors usually need less information about products that are approaching the end of their life cycle than about those that are newly launched.

- How much help do medical professionals need to distill and interpret the medical information that is most relevant? The number and complexity of available products—the level of “noise” in the information landscape—drives the answer to this question. For example, our research indicates that oncologists, like many other specialists, seek extensive information on the products they use. Most oncologists, focused on a broad range of cancers with many possible treatment options, are inundated with data and visits from medical science liaisons (MSLs)—representatives from pharma-company field medical teams—on a regular basis. Oncologists are more likely than other specialists to demand that MSLs be adept at sifting through the available data to produce a set of customized information that is especially relevant for them and their patients.

Understanding the Needs of Medical Professionals

Most of the medical affairs teams we have worked with have a wealth of institutional knowledge but lack a deep, objective understanding of the specific information needs of the medical professionals they serve. They also tend not to differentiate among the needs of various stakeholders who make or influence treatment decisions, including key opinion leaders, other physicians who specialize in a specific disease and treat a large volume of patients, and nonspecialists. This lack of differentiation likely explains why physicians’ satisfaction with the medical-information offerings of most pharma companies is far from high.

Many of our clients know that their strategies could be more progressive and that their tactics could have more impact. When we work with these clients, we recommend a three-step approach.

Find out what’s needed. The first step is to conduct comprehensive qualitative and quantitative research with medical professionals in order to better understand their medical-information needs. Pharma companies must identify the distinct “ecosystems” and practice types of medical professionals who treat patients with a specific product, and they must understand how the needs of these professionals’ vary from ecosystem to ecosystem. Companies also have to assess how well medical affairs is meeting the needs of each ecosystem.

We recently helped a U.S.-based medical affairs team optimize its information offering for a specialty product. Our research indicated that the team was doing an effective job of providing medical information to key opinion leaders, who had been their primary focus since the product’s launch. However, the team’s performance in meeting the needs of clinical specialists, who, as a group, treated 45 percent of all patients with the disease targeted by this product, was lagging behind that of competitors.

Digging further into the data, we determined that these specialists had deep expertise grounded in a significant amount of clinical experience. They wanted practical and up-to-date information, but they had little time to sift through the latest clinical findings. In addition, they wanted to be visited by MSLs even more frequently than did key opinion leaders—preferring concise summaries of information so they could get back to their patients and apply what they had learned. Our client’s MSL team rarely visited this set of physicians.

On the basis of these findings, the client implemented several changes. It expanded its field-based medical team, creating an entirely new role to serve the specific needs of these clinical specialists. The new team members are focused on providing these physicians with more frequent and concise interactions. The client is also increasing its emphasis on training, ensuring that each member of the field team knows how best to engage physicians and has the knowledge and tools needed to serve each ecosystem most effectively.

The client implemented the recommendations within a few months of our engagement, and we followed up a year later to track progress. Our follow-up quantitative research with physicians indicated that those who had been visited by the expanded field team were significantly more satisfied with the medical information they had received than those who had not been visited. The results were summarized in an updated “metrics scorecard” that the client will refresh on a regular basis to track progress and inform the evolution of its medical affairs approach.

Understand how needs evolve. The second step in improving medical affairs strategies is to develop a process that routinely reassesses how medical-information needs evolve as established products mature and new products enter the market. We find that, in many cases, the insights generated by MSLs in the field are not systematically captured, shared internally, and translated into action. More often, MSLs spend hours each week inputting physician visit statistics into a database, but the most salient learnings from their visits fail to reach the medical directors who define the research agenda. As a result, the medical strategy does not evolve to fully meet physicians’ needs, and physicians think that their voices are not being heard—a sure-fire way to lose their trust.

The best solutions are simple—for example, a user-friendly knowledge-management tool and a process to guide its use—and they can deliver real impact. At one pharma company, MSLs transfer insights from the field into a central database, which is then routinely mined for information that is synthesized by a dedicated internal resource. These insights are regularly shared in field medical-team discussions, as well as with other relevant functions, such as medical-information groups.

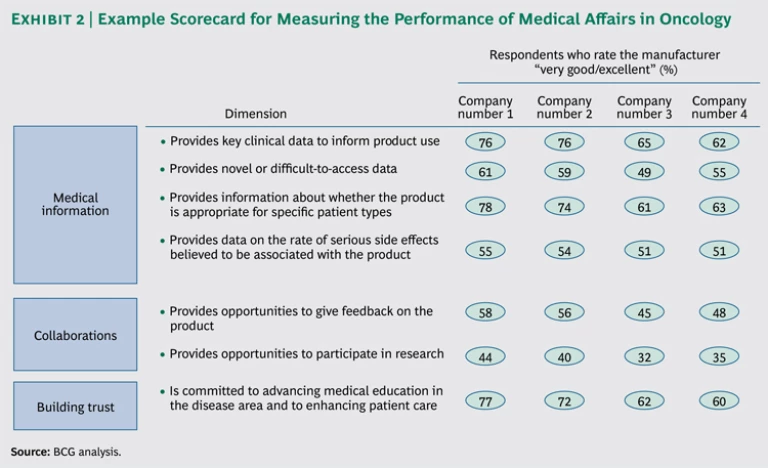

Keep a scorecard. The last step is to track the organization’s progress in meeting the information needs of medical professionals. In medical affairs, the most effective way to measure success is through direct feedback from physicians. This can be compiled through a concise survey that focuses on the aspects of medical information that are most critical to physicians and includes comparisons with competitors. We have helped clients design and field surveys to establish a baseline metrics scorecard. (See Exhibit 2.) This survey can be readministered on a regular basis and used to inform refinements to the medical-information strategy over time.

When these three steps are implemented, a virtuous circle develops. Members of the medical affairs team are more motivated because they can see their insights translated into action and impact. Physicians are more engaged, and the medical information that is generated and shared is much more effective in meeting their needs. As a result, physicians are able to make more informed treatment decisions, improving outcomes and increasing physicians’ trust in the pharmaceutical product and the company that provides it.

Earning Trust

Tensions within a medical affairs organization over vision, strategy, and tactics can be resolved by aligning the team with a shared mission of building medical professionals’ trust. According to Bruce Henderson, The Boston Consulting Group’s founder, trust can be defined as the perception that a company, or an individual acting on behalf of a company, is subordinating personal interest, has no undisclosed motives, and has fully taken into account the values and consequences for all those affected by a decision. In other words, trust is generated when physicians believe that a pharmaceutical manufacturer’s interests are aligned with their own.

We have identified four primary ways that medical professionals come to trust a pharmaceutical product, as well as how each way can be influenced, directly or indirectly, by medical affairs:

- Medical professionals have more trust in a product if they can easily review the clinical data. In this regard, the job of medical affairs is clear: it can build trust by generating the data physicians need and sharing the information transparently. For example, developing a robust safety-communications strategy is critical. Do you proactively share safety data on an ongoing basis? If a crisis occurs, how will key stakeholders first be informed—by your medical team or by the media? Will MSLs take responsibility, or will they blame corporate headquarters for not keeping them in the loop?

- Physicians also come to trust a product through experience—their own and others’. Medical affairs organizations have more impact here than they might think. Although they cannot directly influence what happens once a physician prescribes a product, they can provide the information physicians need to improve the likelihood of a positive outcome. And they can take advantage of strong relationships with key opinion leaders in order to help build other physicians’ trust in the product.

- A good relationship between medical professionals and the pharmaceutical manufacturer can build trust in a product as well. This relationship can be fostered by high-quality MSL interactions. The important thing is for MSLs to maintain their focus on building trust and advancing patient care as end goals, with relationship building as an enabler. This focus can be disrupted if the mission is not clear. As one clinical specialist stated about MSLs, “Sometimes I get the sense they are out there in the parking lot, memorizing my kids’ names. But that’s not what I’m interested in… I don’t need another friend.”

- Finally, medical professionals will trust a product if they have a positive perception of the manufacturers’ reputation. Medical affairs can have a direct impact here, but this perception is also shaped by a much broader set of interactions between physicians and various representatives of a pharma company, including sales reps, key-account managers, and members of the field medical team. Ensuring that these interactions are coordinated and streamlined is critical to building trust.

Assessing the Health of Your Medical Affairs Strategy

The medical affairs landscape is changing rapidly. The best organizations do not look backward at benchmarks and lagging indicators. Instead, they clarify their mission, focus their efforts, learn about the needs of the physicians they serve, and innovate to meet those needs.

When we work with medical affairs clients in preparing for a new-product launch, we administer a “health check” to assess organizational readiness. We invite you to consider a few of the questions we pose. Consider them in the context of your own products.

- Is the level of medical affairs investment commensurate with the importance of the new product to the company (as opposed to being distributed equally across all brands)?

- Is the medical affairs strategy customized to the new product and its defining characteristics?

- Is the mission of the medical affairs organization aligned internally, and does it help guide the actions of its personnel?

- Is the medical-information offering tailored to meet the needs of the specific ecosystems of medical professionals?

- Are hiring and training plans for MSLs designed with an understanding of which MSL attributes (such as clinical acumen, active listening, and responsiveness) are most important to physicians?

- Is there an objective understanding of how your medical affairs organization is performing relative to that of competitors?

If the answer to any of these questions is “no,” then there is an opportunity to evolve your medical affairs strategy.