For years, companies have used digital supply chain technologies to improve service levels and reduce costs. But the inability to connect disparate systems, provide end-to-end visibility into the supply chain, and crunch massive amounts of data, among other issues, has prevented many companies from achieving the full potential of their supply chains. Now, thanks to the wide availability and adoption of much more powerful digital technologies, including advanced analytics and cloud-based solutions, companies are generating dramatically better returns on their investments.

A study by The Boston Consulting Group shows that the leaders in digital supply chain management are enjoying increases in product availability of up to 10 percentage points, more than 25% faster response times to changes in market demand, and 30% better realization of working-capital reductions, on average, than the laggards. They have 40% to 110% higher operating margins and 17% to 64% fewer cash conversion days. With the help of three key strategies, these agile companies are quickly leaving behind their less nimble competitors.

What the Leaders Are Doing

With so many buzzwords out there, it can be hard for executives to discern the most strategic areas for investment in supply chain technologies. To help separate the signal from the noise, we have drawn on our work in this area with dozens of companies to distill the strategies that leading companies are using to achieve results today.

Fix performance gaps. Some companies apply digital technologies to relatively straightforward supply chain problems that are too cumbersome to address with conventional approaches. For example, advanced analytics help managers dynamically calculate optimal inventory allocations and forecast demand more accurately—two areas that have always been difficult with traditional processes based on static, monolithic enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. Often, newer digital technologies ride on top of legacy systems, making them more flexible and easier to operate. That avoids the workarounds that often plague new-technology rollouts and encourages employees to use the integrated system rather than dispersed Excel spreadsheets. Ultimately, companies can create a single version of the truth, thus improving decision making, customer service, and asset and working-capital utilization.

Consider the goal of transparency in the supply chain. Real-time visibility into which goods are in the warehouse, which trucks are on the road, and which machines are running is difficult to achieve with traditional ERP systems. A global supply chain network generates a huge amount of data per minute, and it takes a massive amount of machine intelligence to filter the information and present it in a way that is easy to understand. Digital technologies can perform those tasks automatically, giving employees the insight they need to optimally steer the global network.

Or take order-to-cash processes. When companies receive orders, they often use manual techniques for tasks such as checking the availability of individual products. Digital order-to-cash tools, in contrast, use intelligent and adaptive algorithms to handle up to 95% of transactions automatically; improved ERP tools help humans deal with the remaining 5%.

After years of showing more promise than results, radio-frequency identification (RFID) is also generating value as a result of focused applications—if companies exploit the big data streams in a meaningful way. For example, a European fashion retailer with $1 billion in revenue has installed RFID gates in every store to track and manage in-store replenishment. The result is drastically increased on-shelf availability of products. Thanks to insights from the massive amounts of data that RFID sensors produce, the retailer can better understand in-store replenishment cycles and thereby improve the efficiency of replenishment from back rooms and warehouses or enable direct delivery to stores. As a result, sales are rising by 2% to 3% and store delivery costs are falling by 3% to 5%.

Innovate business processes. Digital supply chain technologies are helping some companies achieve a step change in performance in more complex areas. Consider the potential of automated replenishment to transform manual processes. Amazon, for example, offers the Dash Button, an Internet-enabled device that consumers press—without having to log on to an account—to reorder laundry detergent, diapers, and other grocery items.

Cross-functional teams whose members are colocated in hubs known as supply chain control towers are another innovative example. The teams monitor and direct activities across the supply chain, taking advantage of real-time data about demand, inventory, capacity, and other factors to fine-tune the global network in a way that was not possible before. Advanced analytics help the team get at the root of performance issues, develop strategies to deal with supply chain disruptions, and improve delivery service and speed.

For example, a global life-sciences company that generates nearly half of its $3 billion in revenue through an e-commerce platform uses a control tower and advanced analytics for replenishment and inventory planning. Depending on the pattern of customer clicks on the website in a country or region, a team member can adjust inventories even though customers have not yet placed orders. The company can also hold more stock in the right locations, which decreases the lead time promised to customers and increases their willingness to buy.

In the past, a company gave a customer a delivery date based on outdated calculations of the time it would take to get components from suppliers, assemble products in the factory, and perform other steps in a heavily siloed supply chain. It was often impossible to unify, analyze, and interpret all the information needed from different computer systems and to construct a reasonable end-to-end representation of the supply chain.

Now, increasingly sophisticated and integrated control-tower technologies can automatically track components down to the individual unit in real time, enabling teams to predict delivery times much more accurately, quickly reroute parts around disruptions, and communicate solutions proactively to customers when things go wrong. Some customers will even pay more for up-to-the-minute supply chain information and reliable delivery of mission-critical components found in everything from mobile phones to jet engines. As a result of control towers, revenues and profits improve as companies speed up supply chain activities, increase efficiency, and uncover new revenue streams.

In addition to establishing control towers, companies can find more intelligent and integrated ways to balance supply and demand in asset-intensive, inflexible production systems. A global chemical company, for instance, introduced an advanced allocation algorithm to decide which customers should receive goods that are in limited supply. On the basis of information the system provided about the cost to serve a customer and expected margins, managers could determine the optimal

allocation.

The new asset-utilization system allowed the company to switch to a customer-centered approach based on supply and demand. As a result, margins rose by an average of 0.5 percentage points. We’re seeing many other innovative uses of big data and advanced analytics that are yielding substantial results, such as dynamic route-network visualization, demand forecasting, and distribution network planning. (See “Making Big Data Work: Supply Chain Management,” BCG article, January 2015.)

Disrupt the supply chain. Leading companies are using digital supply chain technologies to redesign their operating models and go-to-market approaches in order to generate significant growth in revenues and margins. Companies can find new routes to customers, decentralize activities, and substantially speed up delivery, among other tactics.

For example, a company can eliminate a distribution channel by developing direct-to-customer capabilities in-house, powered by digital technologies, thereby saving on third-party distribution costs and capturing the margin that distributors previously controlled. It can fully automate filling and packing with advanced robotics to enable small-scale distribution, at a tenth of the cost a decade ago. More readily available advanced technologies, such as the YuMi collaborative dual-arm robot from ABB, make it possible to move final assembly or processing closer to end customers and thus improve service. Cloud-based solutions also let centralized expert teams oversee increasingly complex networks.

Building products radically closer to the customer in mobile manufacturing units can speed up delivery substantially. Amazon has filed a patent for a mobile 3-D-printing delivery truck that would make it possible to print out a customer’s order from a data file sent to the nearest vehicle. This innovation would let the company get items to shoppers much more quickly and reduce its warehouse space.

We’re already seeing disruption in the pharmaceutical business thanks to more detailed and accurate sensing of demand. US law requires companies to give each drug a unique ID and track it throughout the supply chain to battle counterfeiting. By placing sensors at the bottom of a pill bottle, companies can also track whether patients are taking their medications. The fill level can be transmitted in real time, allowing drug companies to ship another bottle to the pharmacy and then to prompt the patient to refill the prescription.

How to Begin

To put these strategies into practice, operations leaders we’ve worked with move through the following stages.

Immerse yourself in the possibilities. Companies should put their best people to work scanning the landscape of digital supply chain management. This “digital immersion team” can collect innovative ideas from outside the company—even from other industries—about ways to innovate and disrupt their business rather than simply improve existing processes. Team members must know how to tap into the expertise of new people, find applications from other industries, and improve on promising ideas. Visits to leading technology companies in digital hotbeds such as Silicon Valley and to road shows in which vendors display the latest digital technologies can jump-start the process.

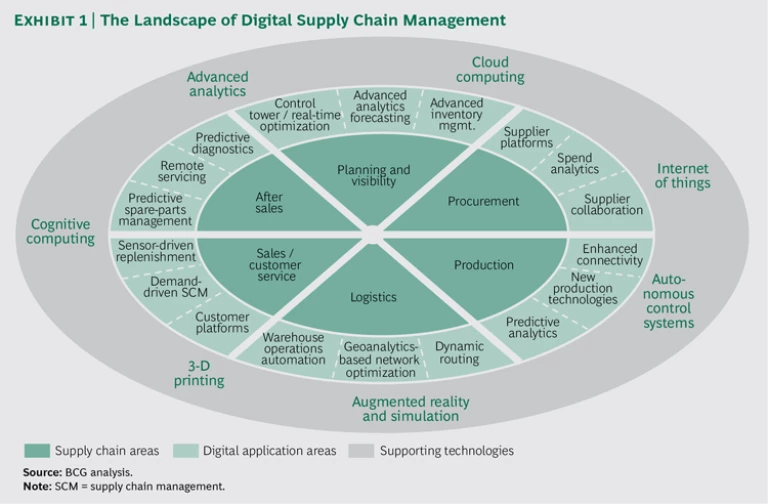

To organize this exploration of the landscape of digital supply chain management, we have developed a map of the major areas of activity to use as a starting point. (See Exhibit 1.)

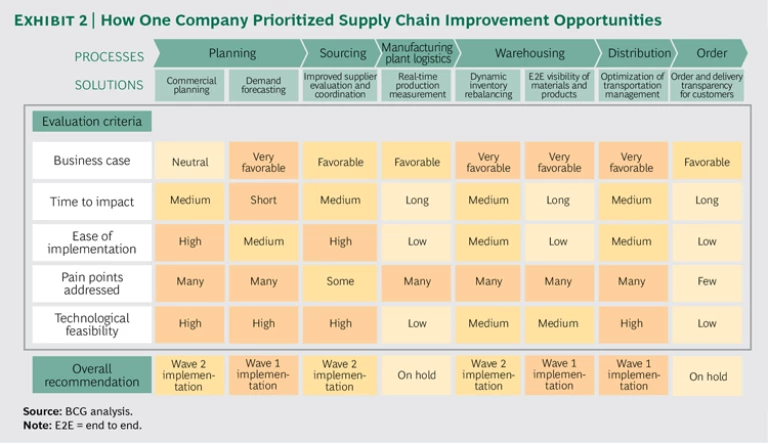

Prioritize the opportunities. Out of the hundreds of ideas that may result from this research, companies should select the ones that could be relevant and useful—the digital applications that have the potential to create significant value for the business and address gaps in performance. Managers can then map those ideas against current business challenges in order to identify areas of alignment. Finally, they should develop a business case—based on the potential uplift in sales and decrease in costs or inventory, for instance—for the opportunities that seem the most relevant, realistic, and financially rewarding. (See Exhibit 2.)

Launch pilots. Following the immersion and prioritization phases, companies should design a handful of pilots that can help them learn what works before they scale initiatives throughout the company. For example, the design phase of the pilot could look at elements of the supply chain that might be candidates for a new performance-management dashboard.

As they roll out pilots, leading companies are testing ideas on a small scale in a high-priority area of the business, selectively refining the approach and identifying new opportunities that emerge. To get the best results, they assemble a group of people to lead the project who can constructively challenge and develop ideas. If a pilot proves successful and applicable to other areas of the business, companies develop an implementation plan that includes the high-level business case and the resources required. Securing senior-level buy-in and developing a change management process are often essential before companies can take pilots to scale.

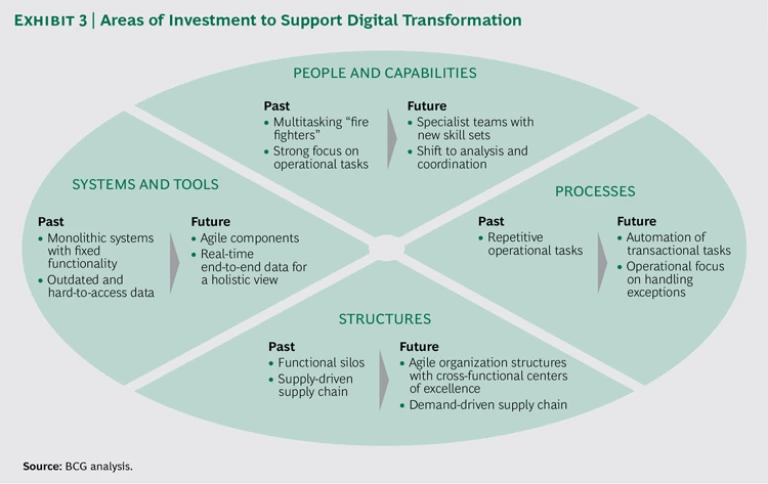

Build the infrastructure for success at scale. Even the best-designed pilots will fail if the organization is not ready for them. Companies often need to build capabilities, systems, structures, and processes unique to their industry and business context in order to succeed. See Exhibit 3 for areas where companies we work with frequently need to invest.

Digital technologies often require a substantially different skill set than traditional supply chain tools do. Take the role of the demand planner. Whereas the planner used to simply collect sales information, today the role calls for highly developed analytical skills. Statistical forecasting engines, for example, require constant maintenance from data scientists, who adjust parameters and blend statistical methods. One life-sciences company employs 20 data scientists to constantly check and adapt the algorithm that guides global replenishment within its warehouse network in order to ensure the best possible customer service.

Going digital also has major implications for organization structures. Companies must adapt to increasing decentralization, develop new governance models, and centralize the right activities to achieve economies of scale. Other changes involve transitioning from monolithic systems to “app style” solutions on the cloud and more automated process handling that focuses on exception management rather than on repetitive tasks.

Digital supply chain management has matured and is generating substantial value. Organizations need to move quickly to apply the highest priority opportunities to their business and industry context. They must find the right mix of fixing performance gaps, innovating business processes, and disrupting the supply chain.

Companies cannot afford to wait. The competition is already making moves, and the leaders in digital supply chain management are building a financial advantage that will be more difficult to overcome with each passing year.