The fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry is in the midst of structural changes: headwinds are intensifying, scale advantages are eroding, and negotiating power with retail players is waning. Despite these challenges, the best FMCG companies have been able to consistently create value in recent years.

The 2017 Consumer Value Creator Series

- North American Airlines Take Off

- Can Traditional Retailers Counter the Online Threat?

- Capitalizing on the Demand for Durables

- Why Consumer Goods Companies Need to Build, Buy, and Broker

In 2017, BCG conducted its annual analysis of TSR, looking at 2,343 companies across 33 industry sectors, including 83 organizations in the consumer FMCG industry.

This downward trend, though slight, highlights the broader pressures that leaders in the sector are facing. Management teams at FMCG companies will need to take action if they are to effectively compete in an increasingly challenging environment. Specifically, they need to find their way back to strong, consistent value creation by employing what we call a build-buy-broker approach.

Growing Challenges

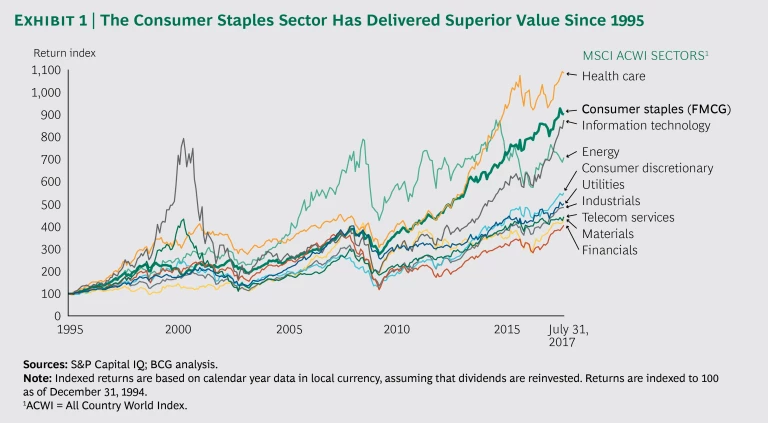

The FMCG sector has long benefited from attractive dynamics, and many FMCG players have reliably created value over time. Consumer staples have outperformed every sector except health care in the MSCI All Country World Index over the 22-year period since the founding of the index in 1995. (See Exhibit 1.) For much of that period, FMCG companies were able to grow by capitalizing on strong tailwinds as economies developed, incomes rose, and consumers turned to packaged goods for convenience and quality. The most successful companies developed and nurtured strong brands that tapped into consumer demand and warranted higher prices. Size mattered, too: large companies were able to create strong scale efficiencies all along the value chain, from sourcing to manufacturing and distribution. In addition, a fragmented landscape limited the bargaining power of retail players. These dynamics paved the way for FMCG leaders to generate consistent, attractive returns.

More recently, however, these favorable trends have been slowing, and some are even reversing. Growth is stagnating in developed markets, and the rate of economic development and per-capita consumption expansion in emerging markets is slowing. What’s more, the retail landscape continues to consolidate, with ever more powerful buyers emerging in an array of new formats and channels. Combined, these shifts are putting significant performance pressure on the leading legacy players in the sector.

The erosion of scale advantages for big players has changed the nature of competition. Megabrands have lost traction in many categories, as small, nimble competitors have proliferated with a range of new products. These companies can now “rent” production capacity, which requires far less capital, and they can reach consumers online, rather than having to work through traditional retailers. They can also market themselves virally, with cutting-edge consumer engagement models, instead of purchasing expensive advertising. In North America, some $22 billion in sales shifted from large companies to smaller companies from 2011 through 2016. (See “How Big Consumer Companies Can Fight Back,” BCG article, September 2017.)

The erosion of scale advantages for big players has changed the nature of competition.

In addition, a second category of new players is also reshaping competition in the FMCG sector. These so-called financial players are building large platforms across many FMCG subsectors through an aggressive agenda of consolidation and cost-cutting, along with changes in culture and infusion of new talent, to create significant value for shareholders. Legacy FMCG leaders are struggling to compete with the efficiency and effectiveness of these new competitors, leading to increased pressure from investors.

The Top Ten

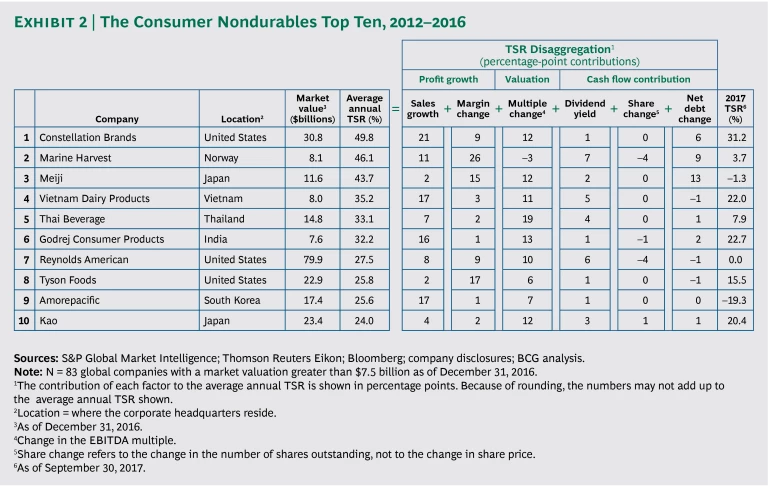

Even in a complex market with increasing headwinds, some companies have been able to outperform the pack. For the period we analyzed, the top ten FMCG players generated average annual TSR of 32.6%, up from 29.6% for the top ten in last year’s study. (See Exhibit 2.) These top performers are creating greater value using a variety of strategies.

For example, Constellation Brands—which owns beer, wine, and spirits brands and finished first in this year’s rankings—has succeeded with a balanced growth strategy. It has combined product innovation with small acquisitions to shift its product mix toward higher-margin, premium offerings. It also modernized manufacturing facilities, expanded its sales force, and invested in digital tools to boost sales capabilities. That balanced approach led to strong value contributions from sales growth (21 percentage points), changes to the valuation multiple (12 percentage points), and margin change (9 percentage points).

In contrast, Tyson Foods—another top ten player in this year’s rankings—created value largely through a series of acquisitions and discipline in generating synergies. In 2014, Tyson bought Hillshire Brands, which had a total enterprise value of about $8.5 billion, leading to estimated synergies of more than $700 million. In 2017, Tyson bought AdvancePierre Foods, which sells frozen foods and has a sizable food service division; AdvancePierre was worth about $4.2 billion at the time and will lead to another $200 million in synergies.

And Vietnam Dairy Products grew rapidly by investing in e-commerce and digital marketing capabilities, along with developing innovative nutritional products. For example, the company launched Vietnam’s first certified organic dairy product line and expanded its line of fruit-infused fresh dairy-based drinks and enriched dairy powders.

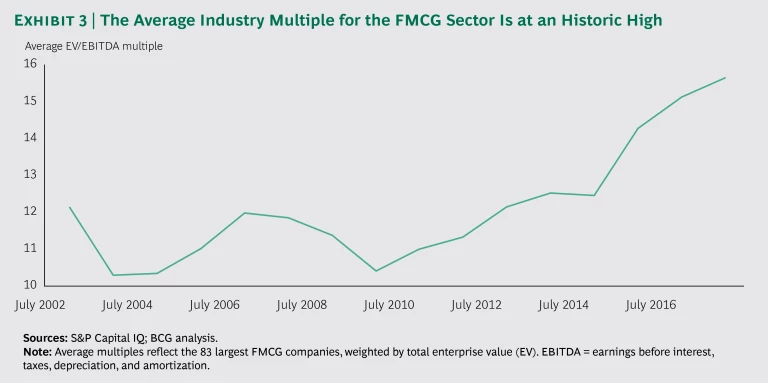

Across the top ten, however, much of the value creation came from expanding valuation multiples. Collectively, the top ten performers derived almost half of their value creation from multiple expansion, followed by sales growth, margin improvements, and changes to cash flow. (The industry was even more reliant on multiples—and less on sales growth—than the overall average across all sectors.)

Thanks to the historic run-up in global stock markets, multiples are now approaching all-time highs, which means that companies will probably not be able to continue expanding multiples for much longer. (See Exhibit 3.) Similarly, given the changing dynamics in the FMCG sector, it is no longer enough to rely on market growth and scale. Instead, companies need to create value through a balanced approach that emphasizes sales growth, profitability, and capital efficiency.

Imperatives for FMCG Leaders

To create value in the future, FMCG leadership teams will need to follow what we are calling a build-buy-broker approach.

Build. The first step is to continue building the company organically, preserving scale benefits while reinvesting in critical new capabilities along the value chain. At a minimum, successful builders implement a series of baseline measures to increase efficiency, such as systematically improving pricing through net revenue management, optimizing the return on marketing investment, deploying zero-based budgeting processes to reduce costs, and streamlining the organization. Operationally, winning builders use digital tools to improve supply chain performance through planning assisted by artificial intelligence, automation in factories and warehouses, and greater digitization among the sales force.

Builders also need to drive the next-generation capabilities needed to create a competitive advantage in a far more dynamic market. This comes down to four priorities:

- Upgrade from traditional consumer research to demand science. Rather than basing their marketing approach on demographic segments, companies need to understand how the demand for their product changes for any given consumer, depending on that person’s specific situation and needs—a concept we call demand-centric growth. (See “Demand-Centric Growth: How to Grow by Finding Out What Really Drives Consumer Choice” BCG Perspective, September 2015.)

- Reinvent consumer engagement. Many FMCG companies have launched digital transformations to roll out precision advertising, customized content, and viral marketing. The next step is to use big data and artificial intelligence to engage with each of their millions of customers on an individual basis.

- Embrace value-added complexity. In a market where niche brands are gaining momentum, companies must use their understanding of consumer demands to determine which long-tail products and variations satisfy their customers and thus justify the complexity in operations that those products add.

- Reshape your organizational DNA. After decades of focusing on scale, efficiency, and control, FMCG companies now need less-rigid organizational structures. To compete against smaller and more entrepreneurial companies, big players need to embrace such agile principles as cross-functional teams and experimentation to break down hierarchies, speed decision making, and translate consumer insights into new products.

Buy. The second step is to explore potential inorganic paths to improve value creation. In this dynamic environment, it is critical for FMCG players to seek transactions that can increase their exposure to high-growth geographic markets and categories and enhance their structural and capability advantages. Of course, it’s important to be selective: FMCG valuations are high, and many players have destroyed value in the past by overpaying for growth or by failing to integrate an acquired asset. But consolidation will continue as FMCG leaders look to boost organic growth by expanding exposure and scale and as financial players continue to build scale platforms. And as the industry continues to reshape, it will be important to remain active in M&A.

Successful buyers in FMCG share a number of common practices. They align their acquisition strategy with their overall business strategy. They are proactive about building a pipeline of potential moves, both through the central business-development function and through individual business units (through managers that are empowered to hunt for deals). The most successful buyers are also skilled in evaluating, structuring, and executing transactions, and they are extremely rigorous in how they integrate newly acquired assets into the company.

Broker. The final key step for FMCG leaders involves taking advantage of favorable market conditions to create shareholder value by finding the right owners for some (or, in extreme cases, all) of the existing assets within the portfolio. This can range from minor moves to clean up the portfolio—selling noncore assets that are a poor fit and a drag on performance and management time—all the way to the major move of positioning the entire company as an attractive target for another buyer. If the build and buy steps cannot sufficiently establish a path to sustainable advantage and growth in this new environment, then the sale of the company should be considered. Given the new competitive pressures in FMCG, the presence of many potential suitors, and the historically high valuation multiples, this could be the best path to value creation for legacy players that face disadvantages they cannot otherwise overcome.

In an extremely challenging market, it is not overstating the case to say that these three steps are imperative for FMCG companies. Leaders need a clear-eyed assessment of their company’s true situation, and they need to take decisive action. Those that continue to wait for the good times to come back will see their options steadily dwindle, even as their more forward-looking competitors—large and small—continue to grow stronger.