When setting their direction, 21st-century CEOs make use of resources unimaginable to their pre-millennium counterparts: digital technologies, AI, vast data sets, democratized information flows, smart new algorithms, and more. They use algorithms as a tool for business analysis and apply algorithmic thinking when making strategic decisions. But is there perhaps some higher-level algorithm that would improve the odds of a successful tenure for today’s CEOs?

A recent BCG research project has been examining CEO tenure in all its aspects and working toward just such an algorithm. The project surveyed more than 450 CEOs in the US and Canada from the “starting classes” of 2009 through 2011. It involved the use of AI and included in-depth interviews with 14 prominent CEOs and board directors. By identifying the most successful CEOs and then isolating and analyzing their distinctive characteristics, we now know the most promising components of an algorithm for a successful 21st-century CEO tenure.

Measuring CEO Success

Success for CEOs is not just about creating impressive short-term results: anyone can lower the bar and then beat expectations. It’s more a matter of fully capturing value and sustaining it over the long term. That might seem obvious, yet CEOs fail—alarmingly often—to follow through. Many CEOs who survive the “sophomore slump” still end up struggling as

The first two criteria, Great Company and Great Stock, are assessed by objective metrics—broadly, strengthening of the company’s competitive position and business economics (Great Company) and total shareholder return over time (Great Stock). CEOs who ranked in the top third on both criteria were characterized as having a “more successful” tenure. The third criterion of success, Great Legacy, is not measurable in the same way but was discussed extensively during interviews. (For further details of the study’s methodology, see the appendix, “An Outline of the Methodology.”) Under our tough grading system, the “more successful” status is hard to achieve: of the 252 CEO tenures that we were able to evaluate fully, just 18% rated as more successful; 47%, as a mixed success; and the remaining 35%, as generally less successful.

These success rates apply regardless of the company’s performance at the time of original handover: for a new CEO, inheriting a thriving company is no golden wand, and inheriting an ailing company is no leaden shackle. After all, maintaining a high-level performance is just as difficult as boosting a low-level performance.

The Components of Success

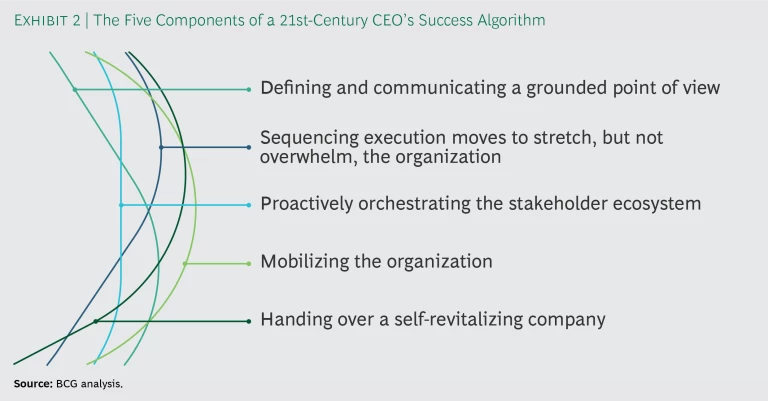

Having shown that a new CEO’s success is negligibly related to the company’s performance at the time of succession, our study then homed in on some factors that definitely do correlate with a more successful tenure. They can be distilled into five broad components: a grounded and compelling strategic narrative, competitively advantaged moves, interactions with stakeholders, engagement of the organization, and a long-term positive imprint. (See Exhibit 2.) It is on these five features that the success algorithm is based. What really differentiates the more successful CEOs is their prowess at, and integration of, all five of these distinctive components. The following account is backed by AI analysis and enriched by the experiences and techniques cited by the CEOs and board directors interviewed during our research.

Defining and Communicating a Grounded Point of View

The more successful CEOs develop conviction about the best way to proceed. They confidently define the company’s potential and map a path toward fulfilling it. They pay close attention to external megatrends and internal signals and then devise a clear strategic narrative, condensed to a “critical few” imperatives. They develop this agenda from a fact base informed by customer pain points, competitive realities, and the economics of competing alternatives. They keep a sharp focus on the real value drivers of the business, including the capital allocation strategy, and they communicate the need for the rest of the organization to maintain that focus as well.

The way that CEOs communicate is very revealing in this regard. Less successful CEOs, in their communications, generally do convey some aspects of their strategic vision, but they tend to neglect elements that would increase the plausibility of their ambitions and would inspire confidence in their ability to execute. For example, they might tell a stirring story based on megatrends but fail to show any links to the value drivers of the business. Or they might devise a stylish mission statement but offer few plausible ideas for realizing it. The more successful CEOs tie together all aspects of a strategic narrative.

“Make sure you have a clearly articulated strategic direction that is rooted in megatrends. Then carefully make strategic bets consistent with those megatrends. Ensure that you build the capabilities required to deliver on those bets, and make the required financial investments with likely returns.” —Indra Nooyi (chairman and CEO, PepsiCo)

“In the end, there are not that many value levers. People think there are many, but in reality, there are few. You should attach actions to the basics of ROI, profit growth, and cash flow in order to improve returns while growing.” —Andrew Silvernail (chairman and CEO, IDEX)

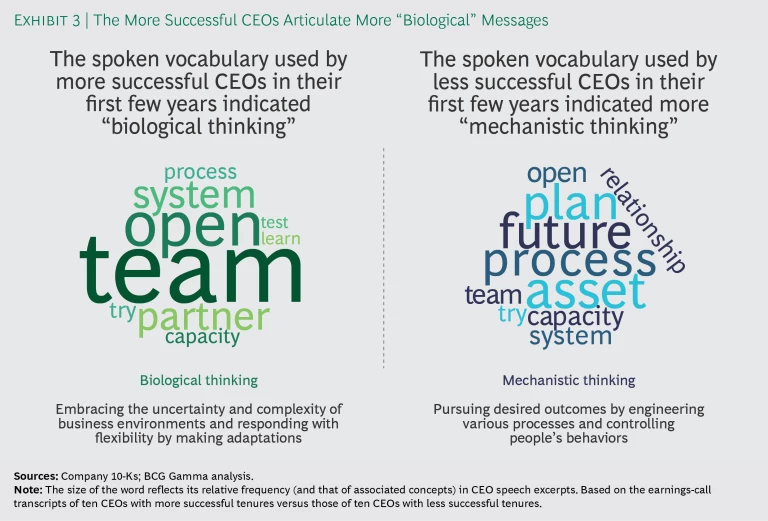

One of our study’s interesting findings, emerging from the natural language processing (NLP) analysis that we used, was that the more successful CEOs, particularly during their first few years in office, tended toward “biological thinking” rather than “mechanistic thinking”—suggesting a greater sensitivity to context changes, greater agility, and a greater readiness to make appropriate

(See Exhibit 3 and the appendix for further details.)

Sequencing Execution Moves to Stretch, but Not Overwhelm, the Organization

The more successful CEOs make their strategic moves at a pace and in a sequence that challenge the organization and avert complacency. They do so by accurately evaluating both the external windows of opportunity and the organization’s internal capacity for change.

“We had to make it understandable to people that the pieces of our transformation fit together and it wasn’t just a series of independent initiatives. There was a sequencing, a logic to what we were doing. You know, you can’t try to do too many things, but if your efforts are reinforcing, you will get more momentum.” —Vincent Forlenza (chairman and CEO, Becton, Dickinson & Co.)

“There are too many organizations that try to pace change in a way that keeps everybody happy. A good way to know that you’re effectively pacing change is to know that people are stressed.” —Frank Blake (nonexecutive chairman, Delta Airlines; board director, Macy’s and Procter & Gamble; former chairman and CEO, The Home Depot)

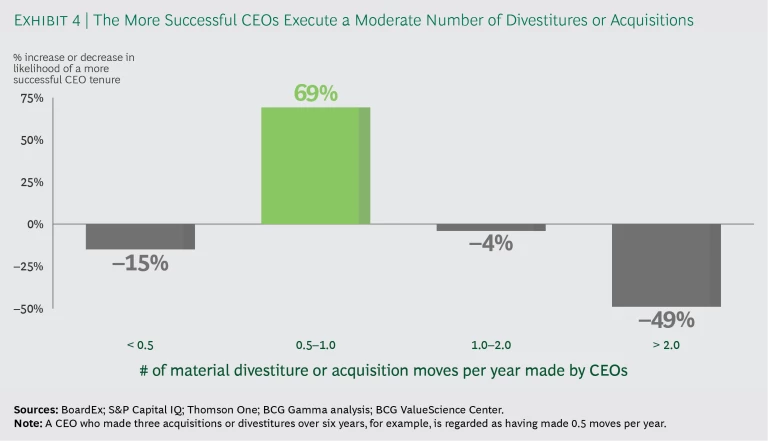

Our research showed how CEOs’ success is strongly linked to both the number and the type of moves that they make. The more successful CEOs made portfolio-reshaping moves—significant divestitures and acquisitions with disclosed terms—in a “sweet spot” of change: enough to stimulate but not so much as to overwhelm. To put it another way, they balanced urgency and restraint, evolving the portfolio rather than letting it sit as is or pursuing too much portfolio change at once (by making more than one deal per year, for instance) (See Exhibit 4.)

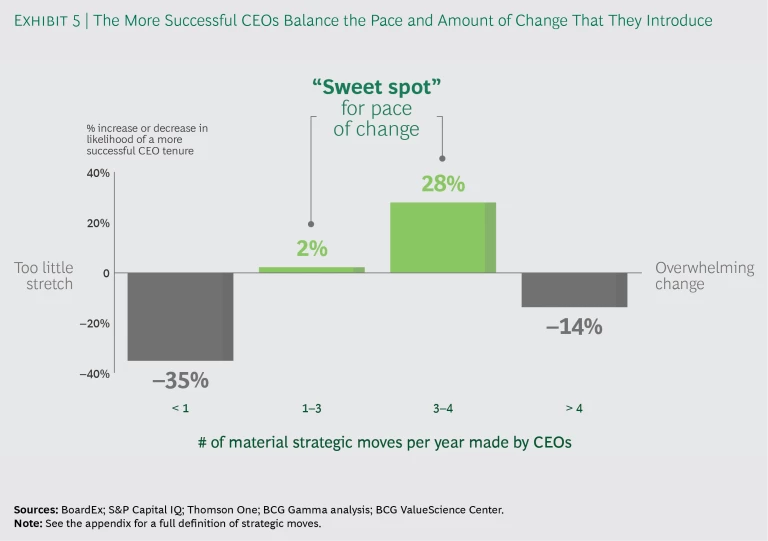

If we broaden the definition of “strategic moves” beyond portfolio shifts, to include capital allocation initiatives and various other significant or material changes affecting company performance, a similar pattern emerges. Exhibit 5 is based on a very broad set of strategic moves, including not just divestitures and acquisitions but also publicly announced transformation programs, major changes to financial policies, substantial restructuring initiatives, and resetting of the R&D-spending profile. Once again, the more successful CEOs seemed to find an advantageous midway point.

In regard to making strategic moves, CEOs and board directors emphasized a number of conducive factors: anticipating industry trends, getting the timing right, building up capabilities prior to making bolder bets, and linking moves to a broader capital allocation strategy.

“The world was consolidating around us. So we had to grow one of our portfolio’s legs—agriculture or nutrition—through acquisition, but we couldn’t do both. We chose agriculture, because we thought it would be easier to sell within health and nutrition, and take the proceeds and buy in agriculture—where people would have to sell, given the environment.” —Pierre Brondeau (chairman and CEO, FMC)

“We pursued a $1 billion cost reduction program and the Dow merger in the first year. That’s a lot to digest. However, if we hadn’t done it, we would have missed the opportunity.” —Edward Breen (chairman and CEO, DowDuPont)

“We started small with a couple deals that were realistically low risk, then went up in a continuum. Walked before we ran.” —Tom Giacomini (chairman and CEO, JBT)

One final note: the pattern of CEO moves is irregular. CEOs tend to make multiple moves in parallel, and some of these moves remain operative throughout the CEOs’ tenure while others are reversed or replaced as things change. And different moves take different lengths of time to embed. So a CEO tenure is best characterized as a series of overlapping cycles rather than as a series of discrete “acts”—opening act, middle act, and final act. With just one exception, all of the CEOs and board directors interviewed for our research study took the view that the discrete-acts model of a CEO tenure is no longer applicable in the 21st century.

“One of the things that’s very clear is that the pace of change in the industry has really accelerated, and technology is affecting everybody. As a result, you cannot think of saying, ‘If you have an eight-to-ten-year tenure, each three to five years you will implement one strategy,’ then say, ‘It’s time to pivot.’” —Raj Gupta (chairman, Aptiv and Avantor Performance Materials; board director, Arconic; former chairman and CEO, Rohm and Haas Company)

“It is not one playbook with one chapter after another. There are many chapters running in parallel—some take longer and some take only a short time, some succeed and some are not successful. Many of them run in parallel—not first act, second act, third act. It is a series of overlapping initiatives.” —Hans-Paul Bürkner (chairman, BCG)

“There are overlapping cycles. Every time you are in the middle, the next cycle is starting. Every disruption starts a cycle.” —Indra Nooyi (chairman and CEO, PepsiCo)

Proactively Orchestrating the Stakeholder Ecosystem

As all CEOs know, a change agenda can be facilitated or impeded by the attitudes and actions of the various stakeholders: the board, the investors, the organization, the government and regulators, and the public at large. The more successful CEOs take pains to understand the expectations—often conflicting expectations—of all these groups, but they also reshape these expectations where appropriate, by challenging outdated assumptions and educating board directors on the new context (megatrends and moves that are part of the CEO’s grounded point of view).

The more successful CEOs tend to gain the confidence of all the stakeholder groups by working with them promptly and personally. These groups might include underrecognized but surprisingly influential sets of stakeholders, such as the company’s pension recipients or a unique customer segment. As far as possible, these relationships should be fully transparent, given that almost everything is out in the open in the 21st century. CEOs can no longer treat internal and external stakeholders differently in their communications, let alone play them off against each other.

“Arguably, the most important aspect of the CEO role is gaining the confidence and support of investors, regulators, and the board. If you don’t have the confidence of the board, you simply cannot succeed. Shareholders are looking for clarity: my belief is that if we are frank and transparent in portraying the current state of the business, and if we accept accountability for what we have committed to deliver, then we will earn their trust and secure their support. The same is true for regulators: we need to establish a rapport, based on mutual trust and mutual respect; create transparency; and deliver against objectives of mutual importance.” —Jay Forbes (CEO, Element Fleet Management; former president and CEO, Bell MTS)

“DuPont has a large retiree stakeholder group in the state of Delaware. Nick Fanandakis [Fanandakis is an executive vice president at DowDuPont] and I did lunch with them to lay out the strategy.” —Edward Breen (chairman and CEO, DowDuPont)

The more successful CEOs seem able to accurately gauge the stakeholders’ level of alignment with the CEOs’ strategic vision and to react accordingly. And the data suggests that successful CEOs draw heavily on a particular set of productive engagement strategies—for example, anticipating and allaying the concerns of activist investors.

“Find out whether your investors are aligned with the company’s strategy. Do they have similar or very different expectations? Having these discussions is important. Maybe you have a few large investors with which you are aligned but also several midsize investors that are unhappy with developments. You have to prepare yourself for potential activist shareholders and how to deal with them.” —Hans-Paul Bürkner (chairman, BCG)

“One CEO hired external advisors to write an activist letter, based on public information, to the board, to know what we would face if an activist took an interest. It drove a lot of different behavior in the board. It was the CEO’s way of managing the board.” —Gary Reiner (board director, Citigroup and Hewlett Packard Enterprise)

Mobilizing the Organization

The CEO can play a major role in engaging and motivating the workforce. In that way, the CEO’s agenda gets transmitted and amplified throughout the organization.

“The CEO is out with missionary zeal, emotionally recruiting people. When you are out speaking to employees, think carefully about how you want to speak to them. Your goal must be to create an indelible picture in their mind of what we will collectively achieve as a company. Focus particularly on the high potentials. As CEO, your goal is to emotionally hook them into the cause. The group should feel like the keepers of the company soul. In small group dialogues, I ask them, ‘If you are one of the 170 people entrusted with the soul of PepsiCo, what would you do?’ It builds ownership and pride, as they feel their contributions are not just for a paycheck but a nobler goal.” —Indra Nooyi (chairman and CEO, PepsiCo)

“In the first six to nine months, CEOs must get a firsthand feeling for the organization—not just for the senior managers. Go deeper in the organization. Roll up your sleeves. Even if you are an internal candidate, you do not know the whole company. It is important to get a sense for yourself, not through the CHRO or CFO.” —Sandy Moose (former lead director, Verizon Communications)

Most CEOs take great care in selecting and aligning their direct reports on the executive team and setting the cadence for them. What sets the more successful CEOs apart is that they tend to go much further than that and deliberately seek strong backing from the rest of the senior leadership team and the extended leadership teams. Rather than delegating executive team members to rally the troops, the more successful CEOs will typically connect directly with a variety of leaders in the organization, reinforcing their loyalty and activating their positive energy. The effect is to cascade the company’s purpose and values down the ranks and increase cooperation across silos, far more powerfully than CEO mandates or formal governance rules do.

“What really united people was BD’s purpose and values. We kept coming back to what we can do for patients around the globe. When people are excited about a company’s purpose, they see that they can make a difference—at an individual and a company level—and a lot of potential problems go away very, very quickly. As you build a purpose-driven culture, make sure that you go beyond your leadership team to the middle of the organization.” —Vincent Forlenza (chairman and CEO, Becton, Dickinson & Co.)

Handing Over a Self-Revitalizing Company

The true measure of success for CEOs is not just what happens to the company while they are in the CEO role but also what happens after their departure—the way that the next generation of leaders maintains the company’s vitality and competitive

So when CEOs admit to being concerned about their legacy, it is not for the sake of gaining personal recognition and basking in the limelight. Their concern is that the improvements they made should be sustainable and should help their successors to succeed in turn. Ideally, the sense of purpose and values that they represented will persist. The talent that they cultivated will keep the momentum going (but will also readily adapt to changing circumstances and adjust the company’s direction if required). The organization will continue to attract further talent, enabling the company to regenerate itself indefinitely.

“The other important attribute of a CEO’s legacy is the regenerative capability of the business to grow its future talent. A strong organization has the ability to populate leadership vacancies from within, drawing on a deep and diverse bench of talent that is knowledgeable of the business and demonstrative of its best cultural attributes.” —Jay Forbes (CEO, Element Fleet Management; former president and CEO, Bell MTS)

“First, as you leave, there are as many exciting growth prospects as when you got there. The CEO has set up growth opportunities. Second, to enable that, you have to ask yourself, every day, ‘Can I improve this team, and build the best team possible?’” —Gary Reiner (board director, Citigroup and Hewlett Packard Enterprise)

“Leave the company in great shape, better than it has ever been before, and walk out with a smile on your face.” —Edward Breen (chairman and CEO, DowDuPont)

Finally, a CEO’s legacy can include a broader social imprint as well. Companies make an impact on society, whether they intend to or not, both locally and globally. The more successful CEOs seem to have a higher-than-average awareness of that impact, and—through directing company resources to create positive societal benefits—contribute to a better world.

“You have a big canvas to make positive change and positively influence the lives of so many people. I hope they remember ‘Performance with Purpose,’ the balance between the short and the long term, and making sure that large companies should deliver performance but also worry about societies and communities we serve.” —Indra Nooyi (chairman and CEO, PepsiCo)

Algorithms informing leadership choices are not a static cookbook of decision rules. Developing and applying algorithms involves constant prediction, monitoring of what’s working and not working, iterative learning, and adapting of priorities to match changing conditions. In our research study, the more successful CEOs were able to accurately read signals from the evolving context and to course-correct promptly and flexibly. By cultivating and constantly fine-tuning the algorithm’s five components, CEOs can boost their chances of creating a Great Company, while ensuring Great Stock along the way, and leaving a Great Legacy.

“The CEO role is a long-running relay race, and you are just the steward of an organization for a period of time. During a CEO tenure, you run as fast as you can, as much distance as you can, and then hand the baton to someone else.” —Carl Stern (global CEO advisor)