Every day, the digital world shines a spotlight on brand inconsistencies. Employees and potential recruits might get one impression online, customers and partners might have another experience, while investors and influencers might see an altogether different picture. The result is brand confusion or worse: brand conflict.

Consumers today, led by the digitally native Millennial generation (ages 18 to 34), expect much more from brands. They increasingly require a holistic and authentic experience across all the online and offline ways they interact with a company. When we surveyed them, Millennials reported that the number one way that brands can engage them is to have an “authentic purpose.” Many consumers expect to engage more actively in a two-way dialogue with brands—and the Internet gives them a megaphone to express their positive and negative opinions loudly. (See The Reciprocity Principle: How Millennials Are Changing the Face of Marketing Forever, BCG Focus, January 2014; and The Resilient Consumer: Where to Find Growth amid the Gloom in Developed Economies, BCG Focus, October 2013.)

The global business environment also demands more from brands. The service sector now makes up approximately 70 percent of most developed economies, and that share is even higher when it includes the many products that have a service component. People have become a critical resource for service-based industries: labor costs are higher than capital costs in many service companies.

Likewise, people have also become an essential component of branding, a field that was once highly product oriented. Brand experiences are now largely shaped by the people on the front lines who interact daily with customers and must meet their rising expectations. Employees have become, in effect, brand ambassadors. Brand management of the future requires, therefore, even fuller and more consistent engagement among the people inside and outside the company—both those who experience the brand and those who represent it.

The problem is that companies too often focus on only one or two aspects of their brand image. Many ignore employees as brand advocates or else narrowly relegate marketing communications for employees and recruits to the human resources department. People often assume that a strong product or corporate brand alone will attract candidates and customers. To become part of its customers’ lives, however, a company’s product and brands will first have to be “lived” by its employees.

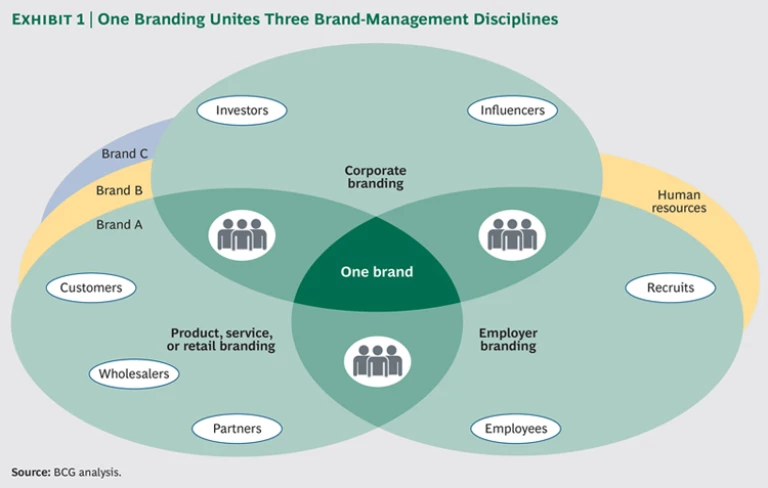

To succeed, companies today must elevate employer branding to its rightful place among the other major pillars of corporate, product, and service brand management. At the same time, they must create harmony among customer experiences with the product, the company, and employees. We call this new concept of integrated, employee-powered marketing one branding. A tight linking of all the aspects of brand management ensures that brands leverage their most significant asset—employees—to create more powerful and relevant brands for today’s changing world. One branding also significantly boosts performance. (See “The Rewards of One Branding.”)

THE REWARDS OF ONE BRANDING

Only the harmonization of corporate, product, and employer branding ensures that everyone involved “pays into” the one-brand account, together raising the brand’s value. We have found that, in many cases, behind this success lies strong employer branding.

Companies that have strong employer brands tend to outperform those that do not. To measure the strength of employer brands, we asked students in MBA programs to rate the attractiveness of prospective employers. A BCG analysis of 39 global companies over the ten-year period from 2003 through 2012 found a positive correlation between the strength of employer brands and the average growth in total shareholder return (TSR).

We found that the correlation between an employer’s brand and TSR was stronger at companies with a strong employer brand than at those with average or poor ratings. Moving into the top leagues of employer branding is, therefore, worthwhile not only from an HR perspective but also for its medium- to long-term impact on company value.

Not every company must be a leader in all three brand-management disciplines. But all companies must gain a basic command of each, as they discover how to differentiate themselves in the areas important to their business. Only then will they achieve more integrated and consistent brands.

The Power of Employer Branding

Even though it has become central to how a brand is experienced, employer branding is frequently the missing ingredient in achieving the promise of one branding. Employer branding represents a company’s brand promise to the people who work there, the people who want to work there, and the people the company wants to recruit. HR leaders cite employer branding as a high priority, but not even 10 percent of prospective employees during job interviews know the key elements of an employer’s brand, according to one European survey.

To succeed in today’s complex business environment and deliver a unified experience across all the brand dimensions that are important to future success—especially through its people—every company needs to define its unique advantages for employer branding and then work hard to cultivate these differentiating factors more effectively. (See Exhibit 1.)

To discern how companies are giving employer branding an equal place inside a unified brand, we interviewed executives in the European operations of ten global companies with leading brands. In our work with companies around the world, we have found these leaders’ insights to be broadly applicable to many other regions.

Consider the success of the employer-branding campaign recently launched by the adidas Group, the world’s second-largest manufacturer of sporting goods, with €14.5 billion in sales; 50,700 employees worldwide; and a brand valued at $7.5 billion by Interbrand as of 2013.

In 1998, Matthias Malessa, chief HR officer of the adidas Group, established an HR marketing department that focused on its external presentation as an employer. “Today, employer branding is a perception index of people inside the company that projects to the outside and says, ‘Check this out. This is how it looks here. If you think it looks good, join us. If not, we’re not for you.’”

For the first time, the features of the campaign were developed with employees on the basis of their experiences working for adidas. The company surveyed employees of all its brands worldwide. Five main branding messages resulted. (See “Employer Branding at adidas.”) Each country has the flexibility to highlight the message that has priority for the employees there.

EMPLOYER BRANDING AT ADIDAS

At adidas, the company has defined the employer value proposition, which consists of five pillars that can be weighted differently to fit local needs:

Sports Lifestyle

At the adidas Group, we are united by sports and the possibility they unlock. We embrace this with a work environment centered on sports and fitness and the flexibility to actively participate. Our roles here contribute to athletic achievements on the world’s biggest stages.

Tribal Membership

What we love and why we love it bring us together as partners and friends, not just coworkers. We work with people who share a common love for sports and fashion. We have fun together.

Globe-Trotting Careers

Our careers at this truly global player know no boundaries. We never stand still, and we love experiencing the world. With corporate locations in more than 170 countries and a truly global mind-set, employees get to travel, work, and live all over the world.

Originality

Life happens. We work around it. Work here is more than work. We recognize and respect that individuals work, live, and think in individual ways. What we wear and how we do our jobs are up to us. We support all stages in life, including the flexibility to parent and maintain a strong career.

True Craftsmanship

What we create changes the worlds of sports and fashion. We thrive on the challenge of constantly improving everything we do. We believe that when we push our limits, we make it possible for others to push theirs.

“More and more young employees are demanding that their voices be heard,” says Malessa. “I ask my people, ‘How do you perceive this company?’ Then I build my employer-branding story based on what they say.” For instance, one message involves social and environmental responsibility. The motto “to make the world a better place” connects this message into a unified product-, corporate-, and employer-brand strategy.

The success factor is that employees are free to share their experiences with the adidas culture online. “In the digital age, it’s important to win over your employees as brand ambassadors, but for it to function, there also have to be rules,” says Simone Lendzian, corporate communications manager. Social-media guidelines orient employees to their rights and responsibilities when communicating as brand ambassadors during work hours.

The company had a lot of discussions about whether each brand in the adidas family—which includes Reebok and Rockport in addition to adidas—needed its own employer branding. “We believe it all has to flow into one employer brand that is all-inclusive and covers the entire company,” says Malessa.

Six Guiding Principles for One Branding

To put one branding into practice, a company must keep in mind six overarching principles about how employer branding relates to its overall brand portfolio.

Credible positioning starts with a well-defined process. At the heart of employer branding lies a convincing employer value proposition (EVP): the promise of value that employers make to their current and future employees. The emphasis should be on the uniqueness of the company. Only with a differentiated strategy can a company achieve competitive advantage.

To ensure that the EVP is relevant and differentiating, it must be based on solid data and integrated into the overall HR strategy process. First, market research compares the internal understanding of the company’s current positioning with the motivations and needs of external target segments. This is translated into a credible brand position and concrete actions and then anchored in the company’s organization structures, roles, and responsibilities. (See Exhibit 2.)

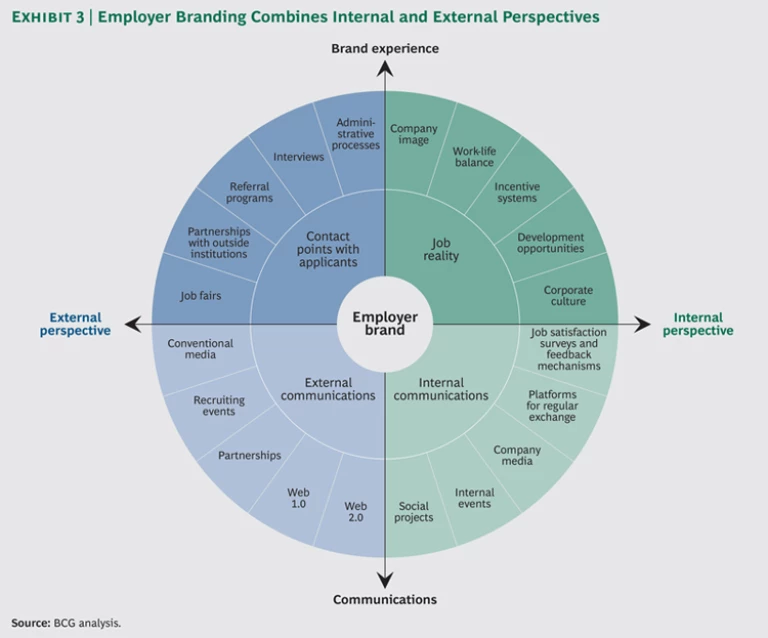

Employee motivations guide employer branding. To attract and retain good people, a company must appeal to both logic and emotion. Effective employer branding uses a “double perspective” of internal and external views to discover the elements of the brand experience that drive engagement among existing and prospective employees. (See Exhibit 3.) Qualitative and quantitative market research can identify motivations that fit the brand, whereas creative techniques can uncover even deeper insights. Rather than simply delegating market research to an outside organization, all internal and external stakeholders should be invited to speak their minds through an active dialogue with the marketing, HR, and strategy departments.

Take the case of the BMW Group, one of the world’s largest automotive companies, with €77 billion in revenues; 110,000 employees worldwide; and a brand valued at $31.8 billion by Interbrand as of 2013. Company leaders break down its employer branding into the motivations that drive its most important target groups and skill areas. For example, engineers can be divided into profiles such as “inventors,” “navigators,” and “realizers,” according to Michael Albrecht, head of international HR marketing and recruiting for BMW. “Job profiles can then be assigned to create a basis for a comprehensive, target-group-specific approach, whereby the messages reference the defined characteristics,” says Albrecht. “In our core disciplines like development, production, logistics, vehicles, and IT, where we usually have a lot of jobs to fill, a targeted approach brings in the best-suited applicants.”

Only a brand that is lived every day can be experienced. Employer branding can be only as strong as the health of the company’s culture.

A true standout is the culture of Google, the world’s largest Internet company by market capitalization, with $50.8 billion in revenues; 45,000 employees worldwide; and a brand valued at $93.3 billion by Interbrand as of 2013. “Our employer value proposition is the result of our company culture as we live and experience it,” says Frank Kohl-Boas, Google’s head of HR in northern Europe. “As our motto says, ‘Do cool things that matter.’ I am convinced that you can recruit and retain knowledge workers only if you give them the room they need to think freely and you offer them interesting work. If you do this, candidates and employees will say, ‘I can earn money elsewhere, but where else can I be a part of things, be myself, and grow?’”

At Google, responsibility for employer branding resides in HR, because it is understood less as a marketing task than as the management of corporate culture. A core team, under the leadership of a chief culture officer, works with local culture ambassadors who support the topic voluntarily in addition to their core jobs. The goals are to find the right people to hire, to ensure the internal multiplication of knowledge, and to provide the freedom for product discovery and invention.

“We don’t do any big marketing campaigns—neither for recruiting nor for Google as a brand,” says Kohl-Boas. “Instead, we invest in employees who develop the brand. We trust that a lot of people will come into contact with our products and associate the company with the quality of our products. If users like our products, the customers and shareholders will come.”

Employees are the best brand ambassadors. The most authentic sources of employer branding are employees who can communicate credibly about the company and make its culture tangible.

Consider eBay, well-known as a global leader in online retailing and payments,

with $16 billion in revenues; 30,000 employees worldwide; and a brand valued at $13.2 billion by Interbrand as of 2013. At eBay, employee referrals are the most important recruiting component by far. “When you shape your employer branding out of the culture and put your people at the center of it, the advantage is that you can motivate them to channel their pride by recommending the company,” says Tobias Hübscher, eBay’s senior manager, European employee communications.

“Referral campaigns save headhunter fees and ad campaign costs and helped us get budget for employer branding and resources for talent acquisition,” he adds. “Basically, we see referrals as being a lot more effective and working better in the recruiting process.”

Social media is only one tool in the toolbox. Despite all the hype about social-media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, every channel must be closely analyzed for its benefits and risks. If a company does not have confidence that it can present itself authentically and engage in open dialogue with consumers through certain mediums, it should not use them until the advantages outweigh any potential damage.

The social-media strategy is well defined at Heineken International, the world’s third-largest brewing company, with €19.2 billion in revenues; 85,000 employees worldwide; and a brand valued at $4.3 billion by Interbrand as of 2013. “When it comes to social media, you have to know exactly what you want,” says Dario Gargiulo, global social-media manager at Heineken International. “A lot of companies do social media only because they think it’s good to have a presence everywhere. Instead, you have to use every social channel differently and with a specific aim. You must take the time to find out which channel should be used for which message.”

Gargiulo recommends focusing on the brand message and consumer attitudes on social media rather than communicating all of the company’s activities. “In social media, you immediately get consumer reactions about what’s important and what’s not,” he says. “It’s about the connection with real life.”

To integrate brand management disciplines tightly, stay loose. The players in one branding are less like a conductor-led orchestra than a leaderless jazz band. In the latter, the optimal combination of players is more important than who leads at any point in time. Well-executed examples of one branding show that there is no universal solution: although HR is often in charge—for instance, at BMW and adidas—several companies we studied maintain an ongoing, constructive conversation among the different components of branding, including marketing, communications, strategy, and HR. The corporate brand often takes the lead when the path forward is not clear.

At eBay, employer branding is jointly managed by the HR, talent acquisition, communications, and marketing departments and covers all eBay brands. Both internal employer culture and external campaigns are steered by communications in the local country unit.

Regardless of the organization design, marketing and HR must work together as equals. Each of the functions has plenty to contribute: HR has the competencies needed for strategic personnel planning and the ongoing development of company culture. And marketing can bring its “detective skills” to the table—by feeling out and establishing a unique positioning for employees and job applicants. (See “The Grand Coalition of Marketing and HR.”)

The era of one branding is dawning. Employer, corporate, and product branding will only grow more closely integrated.

Although we see no one-size-fits-all strategy that can address all the challenges ahead, we have observed this about the leaders: one branding works only if executives in charge of HR and the brand disciplines make it their common goal and have the courage and flexibility to work together.

Companies that are willing to cross organization boundaries and experiment with this new approach now will discover the proven benefits of one branding. Those that do not move in this direction risk falling behind their more integrated and nimble competitors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following companies for their generosity in sharing their one-branding experiences and for allowing us to learn from them: adidas Group, BMW Group, eBay, Deutsche Lufthansa, Deutsche Telekom, Heineken International, Google, Otis Elevator Company, Ottobock HealthCare, and Zalando.

We are also grateful to our BCG colleagues who helped us focus on the topic of employer branding: Katrin Gruber (an alumna), Christian Hense, Maximilian Klante, Philip Specht, Stefan Wamsler, and Tanja Woutskowsky.