To refinance in a crisis, particularly when both operational and financial restructuring are required, companies of all sizes need to get their existing financiers to agree on the appropriate course to be taken and secure fresh money that will allow them to remain viable. Yet refinancing in the changing financial landscape of Germany today is becoming more difficult. While traditional bank lenders are staying in the game, especially in the short term, a material shift is coming.

So, we asked the German restructuring community who would sit at the table in a financing situation going forward—particularly in a crisis. According to those we surveyed, more and more banks will succumb to regulatory pressure, declining to grant new crisis financing and exiting early from troubled loans. Meanwhile, new sources, such as private equity (PE) and private debt (PD) funds, will become increasingly involved, along with international financiers and fintechs.

These shifts are adding both complexity and risk to the financing process. Because midsize companies vastly outnumber large companies in Germany, they have traditionally played an enormous role in the economy. The strategic importance of these midsize companies, therefore, cannot be overstated.

Material shifts are adding complexity and risk to the financing process in Germany.

To examine the topic more closely, we first analyzed Germany’s macroeconomic environment, focusing on the most important indicators for the relevant financing sources. We then performed an in-depth study of the German refinancing market for midsize companies as it stood in 2018.

We began with a survey of 63 restructuring experts, using both a standardized questionnaire and in-person interviews. We asked these experts how the relevance of financing sources that are critical for midsize companies would change over the next few years, particularly for companies in crisis. We next examined 32 refinancing situations that BCG has supported recently in Germany, speaking with partners and project leaders to discover whether our survey findings were reflected in these cases. Finally, we drew conclusions from the research about the impact of the shifting financial landscape on midsize companies in crisis, the lessons learned, and the success factors for those in the refinancing process.

Uncertainty on the Horizon

Expectations for macroeconomic developments in Germany have been relatively good until recently. Nonetheless, the possibility of another downturn in the Eurozone economy cannot be ruled out, given the latest economic indicators.

The German economy has grown steadily since 2010, and the price-adjusted gross domestic product increased 2.2% in 2017, slightly below the average of 2.4% for the European Union (EU). In addition, companies have performed well over the past few years. From 2013 to 2017, for example, the 600 largest companies in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland achieved annual growth of 2.5% in revenues and 6.3% in EBIT, to reach an average EBIT margin of 8.7% in 2017. At the same time, the capital requirements for these companies have grown at a higher rate than revenues—by 6.2% annually.

In line with these favorable developments, companies based in Germany have increased their investment activities over the past few years, thereby boosting the volume of financing required—both for growth and for acquiring new digital technologies. Simultaneously, the low interest rate policy of the European Central Bank (ECB), a key factor behind the positive economic climate so far, has made financing more affordable. A growing number of diverse funding sources have competed to provide that financing, fueled by investor appetite for returns as well as the opportunities arising in connection with digital funding sources, such as fintechs. This new competition is slowly but steadily changing the financing landscape.

Nonetheless, the outlook for 2019 is modest, and several red flags have been raised in recent months. Banks are beginning to report more businesses in distress; the automotive sector, one of Germany’s core industries and therefore a leading indicator, is warning of declining profits; and stock markets in Europe are showing signs of weakness. Added to this, the global trade dispute—in particular between the US and China but also between the US and the EU—along with faltering Brexit negotiations and a potential change of direction in US fiscal policy are all creating uncertainty. A possible resurgence of the economic crisis in Greece and growing public debt in Italy and China are giving rise to additional concerns. Perhaps especially troubling in today’s high-liquidity environment, financing options may be offered to somewhat weakened companies that might not otherwise have been candidates for such offers. These companies, not yet underperforming, could quickly become problematic in the event of an economic downturn or a change in fiscal policy.

Financing options may be offered to somewhat weakened companies that might not otherwise have been candidates.

If a slowdown is indeed approaching, therefore, the need to understand the changing financing market, particularly for crisis funding, becomes urgent. How will midsize companies refinance in the increasingly complex financial landscape, where banks are becoming more and more averse to financing companies in a crisis and new funding sources may not have the experience to navigate that crisis?

A Sea Change for Corporate Financing

In the following discussion, we look first at refinancing situations that BCG has supported in Germany and the results of our expert survey to understand the financing shift at a high level. We then examine individual funding sources more closely and shed light on how each one might affect crisis financing.

Case Study and Survey Results

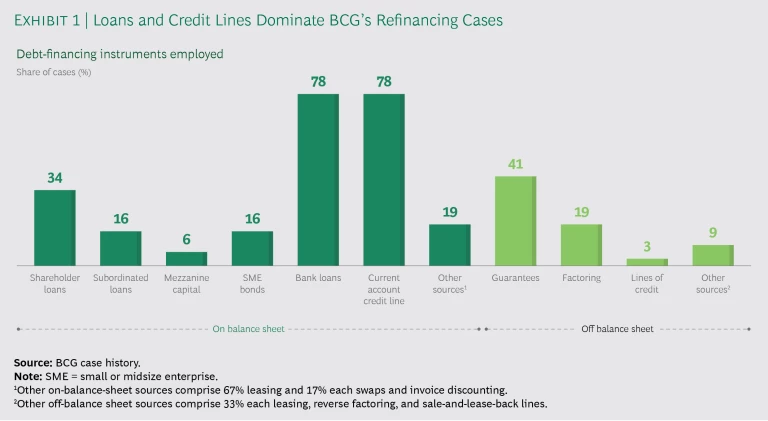

Traditional bank financing has been fundamental for midsize companies up to now. In the refinancing situations that BCG has supported, 78% relied on commercial banks for traditional loans and current account lines of credit as well as bank guarantees, which were used in 41% of the cases. In addition, 34% used shareholder loans, while 16% employed small and midsize enterprise (SME) bonds. (See Exhibit 1.)

The experts we surveyed, however, foresee clear changes in the relevance of the various financing sources. Traditional bank financing will remain important, of course, but 73% of respondents believe its relevance will decline over the next three to five years. In contrast, 76% expect PE and PD financing to grow significantly during the same period. Similarly, 76% expect fintech financing for midsize companies to experience significant growth, at least for smaller lending volumes.

Our respondents also believe that the importance of shareholder financing will remain unchanged over the medium term. However, 32% of survey respondents expect the role of other financing sources—including factoring, mezzanine capital, and German promissory notes, known as Schuldscheindarlehen (SSDs)—to grow. (See Exhibit 2.)

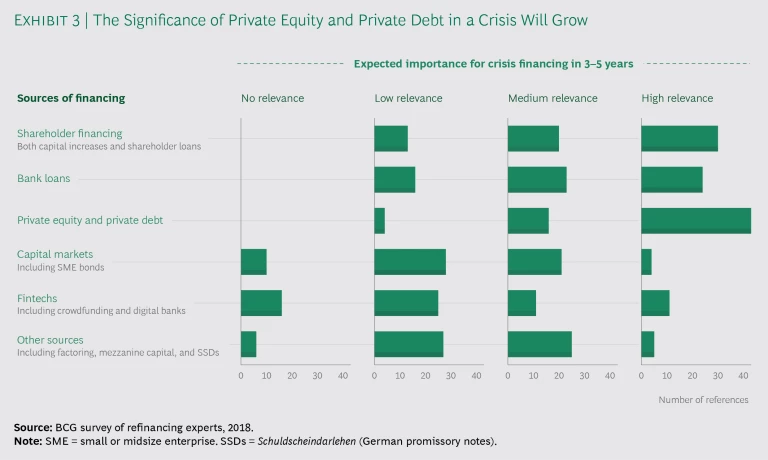

The experts we surveyed expect that when underperforming or distressed companies undergo refinancing, three sources of funding will be the most relevant over the next three to five years: shareholders, banks, and PE and PD. Fintechs and SSDs will play a role as well, but to a much smaller extent. (See Exhibit 3.) Companies facing or undergoing restructuring must therefore be prepared for these new factors if they are to successfully master the restructuring process.

Individual Funding Sources

A closer look at individual funding sources confirms the broad trends identified by our surveyed experts and by BCG’s own refinancing experience. Midsize companies will continue to rely on traditional banks and shareholders for the bulk of their financing, at least in the medium term. But a material shift is taking place with regard to who will sit at the table in a financing situation—particularly in a crisis.

Bank financing faces headwinds. Historically, bank loans have provided the great majority of external financing for corporate growth in Germany, and they continue to do so today, as indicated by an increasing volume of loans. They play a leading role in financing German midsize companies. And because of their prominent position in today’s financing structures, they will continue to be an important financing partner in a crisis, whether by providing bridge loans or rollovers, allowing temporary repayment deferrals, or amending or extending existing financing agreements. Nonetheless, the role of banks is changing as falling margins encourage them to offer easier credit terms even while they work to reduce risk exposures in response to new regulatory pressure.

- Falling Margins. Bank lending margins have eroded steadily, reaching just 1.5 percentage points in 2018, with further deterioration possible. These low margins are compounded by an interest penalty that banks must pay for parking funds at the central banks—a fee that they cannot usually pass through to their customers. Meanwhile, banks are competing more heavily, not only with one another but also with the foreign banks and investors that are currently pushing into the German market. Domestic banks, therefore, are working hard to issue more loans as they attempt to compensate for the erosion of their margins. In fact, we estimate that loan volumes to companies in Germany will increase by around 1.3% per year until 2020 (assuming no major economic downturn), due primarily to the banks’ new lending efforts.

- Covenant-Light Terms. In response to increased competition, banks are sometimes offering easier credit terms, such as fewer covenants and less-stringent reporting requirements, to companies—especially those in relatively good financial positions. But while this maneuver may help banks in the short term, it will ultimately result in higher-risk financing. We expect that, as a result, banks will continue to experience problematic credits in their portfolios, which will come under pressure if the economic situation deteriorates. Lighter covenants may also mean that nonperforming loans will not be discovered as early as they once were.

- Tighter Regulations. At the same time, tighter regulations, coming in response to the global financial crisis of 2007–2008, are forcing banks to raise their lending barriers and improve their risk positions. In fact, the series of guidelines published and amended by the ECB over the past two years includes the guidance on leveraged transactions, issued in May 2017, which instructs banks to either take a cautious approach when lending to companies already in debt or to turn down such companies entirely. In another example, the guidance to banks on nonperforming loans, issued in March 2017, aims specifically to encourage banks to reduce their problem credits. In addition, regulators have required banks to create risk provisions for potential losses at the time a loan is issued, instead of waiting until the loan is in direct jeopardy.

As a result, borrowing will be more difficult for underperforming companies, particularly in the case of an economic downturn.

- Reduction of Risk Exposure. As another consequence of tighter regulations, banks are more likely to sell any at-risk loans not subject to supervision or disposal restrictions at the first sign of a corporate crisis—a trend that is already clearly recognizable. In fact, nonperforming loans as a share of total lending volume in Germany fell from 3.3% in 2009 to 1.7% in 2016. Banks may also begin to limit their risk by supporting only major crisis cases, either selling their smaller exposures or writing them off directly. And they may take greater advantage of their enforcement options, although that is more difficult if the financing is light on covenants, given that such agreements will not be triggered by companies in crisis as early as they would have been in the past.

- Fewer Resources in a Crisis. Despite the foregoing efforts, banks will have fewer resources to handle a crisis than they have had in the past. Recent economic growth, stricter regulations, and bank reductions of risk exposure have led bank workout departments to focus on clients that have larger refinancing requirements and to reduce the sizes of their teams. As a result, lenders have fewer resources available and may have to make settlement decisions based on more limited involvement or sell their exposure to other investors.

To avoid restaffing workout departments as soon as a crisis appears, lenders are pushing for better information exchange and a more efficient restructuring process. This process is likely to include such digital tools as standardized data formats, cloud computing, and information platforms with real-time reporting and online communications capabilities—all of which will improve collaboration between banks and others involved in the financing process.

- Tougher Negotiating Partner. Given that banks’ approach to refinancing troubled companies is changing, the role of banks in the overall refinancing process is shifting, too. They may prefer to take the lead in refinancing negotiations less frequently and to give other lenders, such as PE and PD funds, the opportunity to support the refinancing and help structure the future of the company.

Simultaneously, they will certainly become a more challenging negotiating partner. Their willingness to provide fresh funding in a crisis situation will typically depend on several factors. First, our experts unanimously indicated that banks expect companies to exhaust all options for generating additional cash―including cost reductions, working capital optimization, divestiture of noncore assets, and factoring—before they ask for additional loans. Second, banks are requiring that companies meet ever-higher standards for creditworthiness and performance, including the provision of additional collateral. Both banks and regulators are also demanding more information from borrowers than they have in the past. Finally—and most important—banks must have good reason to believe that a restructuring will have quick, positive results and that the default risk has been reduced to the lowest possible level. Otherwise, they will not be able to meet today’s strict regulatory requirements.

- Factoring as Crisis Funding. As noted above, banks may ask companies to contract with a factoring company—or sell their receivables—before requesting new funds, a proven way to mobilize cash quickly in a crisis. Despite reducing their role in refinancing efforts in general, banks themselves will continue to factor as well. We have seen many companies receive a factoring line of credit even when they already had their backs against a wall financially. However, factoring is only possible when unpledged collateral is available.

PE and PD dive into financing. PE and PD represent increasingly popular options for midsize companies raising capital in Germany. While, in our experience, these companies have been reluctant to think about alternative sources of funding, both PE and PD are becoming more prevalent, and our experts foresee even further growth over the medium term. In consequence, PE and PD will be included in many financing and refinancing arrangements. In fact, two-thirds of our experts say that PE and PD will become more important for crisis financing over the medium term. We are already seeing a trend toward greater PE involvement in BCG’s own refinancing cases, up by 14 percentage points over three years, to 44%, in 2018.

PE and PD represent increasingly popular options for midsize companies raising capital.

- PE Values Up, Deals Down. PE funds traditionally invest in healthy private companies, aiming for value expansion. Their investments tend to be cyclical, as shown convincingly during the global economic crisis. At the moment, PE multiples are growing in response to low interest rates in many locations because capital is cheap and institutional investors are looking for more lucrative investment objects. In fact, many institutional investors put money into PE over a recent five-year period, with around $840 billion of fresh capital raised by businesses worldwide through PE in 2017, nearly double the volume in 2012.

At the same time, the actual number of PE deals has been declining. This discrepancy reflects a difficult situation: while funds have plenty of money to invest, attractive takeover candidates are scarce. As a result, uninvested capital, known as dry powder, reached a record high in 2017 of about $1.8 trillion worldwide. While some funds are responding to high valuations by exercising greater care than they have in the past—even to the point of rejecting interesting deals—other funds are giving in to investor pressure to engage in transactions. They are acquiring control of companies at higher and higher prices and financing these costly investments with ever-greater debt components. The median purchase price multiplier for company acquisitions reached an all-time high of 14 times EBITDA in 2017—well above the average median of 12 times EBITDA from 1990 to 2017 and the all-time low of a median that was 9 times EBITDA in 2009.

Not surprisingly, critical observers have questioned whether the market is becoming overheated and if sustainable value can be generated at such prices and multiples. If a downturn does kick in, portfolio companies are likely to see reduced operating results and therefore have issues gaining value—and paying back their debt. Some may end up in financial difficulties.

- PE Portfolio Company in a Crisis. If one of a PE fund’s portfolio companies experiences a crisis, the rules that apply to other shareholders will also apply to the fund during refinancing negotiations—just more rigorously. The company’s banks will push more strongly for shareholder contributions, given the deep pockets behind many PE investors. In response, the fund must either be willing to reach a compromise, contributing additional funds to avoid jeopardizing its own investment, or use its power as an influential bank customer to refuse to negotiate further.

- Special Situations Funds. We note that some investors look not only for healthy companies but for troubled ones as well. They search for, and invest directly in, companies in economic, financial, or organizational distress. Here, too, transactions have been on the rise, and more capital is being invested. During a recent five-year period, the global volume of distressed private debt increased by an average of 5.6% each year, reaching $222 billion in 2017.

These funds generally buy into debt at a discount and then, depending on their investment strategy, either hold that capital until it can be repaid at face value or convert parts of it into equity. Those taking the latter route hope to benefit from the company’s recovery, ultimately gaining control and then reorganizing the company according to their own plans. When banks sell off risky corporate loans, this move supports the goals of these funds.

We note that for midsize companies in a crisis, negotiating with these funds may be difficult because their agenda differs from that of traditional bank lenders and can be far more demanding.

- PD on the Rise. Although private investors in Germany have traditionally put their money into equity, they are increasingly giving loans directly to companies without broad syndication by a bank. These PD funds constitute a flexible alternative to bank loans for midsize companies. From 2012 to 2017, global PD volume increased by 9.8% annually, thus recording stronger growth than PE—although, at $400 billion, the baseline was much lower.

As a nonstandard form of investment, PD financing can be structured in different ways. Providers are usually funds, operating either alone or under club deals, usually with no more than two or three partners. Typical loan volumes range from €20 million to €150 million, with an average interest rate of more than 5%.

Given the growth of PD funding in general, midsize companies in a crisis are clearly more likely to find representatives of these funds sitting down at the table as they negotiate a refinancing agreement.

- PE and PD are a Tradeoff. At present, even troubled companies can look forward to receiving financial support from PE and PD funds. These funds often provide more flexible and less regulated financing structures, and faster access to liquidity, than do traditional bank lenders. Of course, these benefits come at a price. In the case of PE funds, investment decisions will depend heavily on a company’s potential for growth or, in the case of special situations funds, its potential for recovery. In addition, given that a fund typically buys an entire company, the fund gains control, and debt may be significantly increased.

In the case of PD, the stipulated interest rate is generally higher than that offered by traditional bank loans. In addition, should the company experience a crisis, PD funds’ operations teams may not be as prepared for refinancing as are the banks, with their in-house workout groups. Of course, PD funds that deliberately invest in distressed assets will be well informed about the process and will request either collateral or a senior position in the debt, in addition to charging a high interest rate.

Fintechs are on the horizon. Fintechs are hoping to revolutionize the heavily traditional corporate finance sector. While it likely will be some time before fintechs are accepted by midsize companies as a supplement to their established sources of funding, almost 76% of the experts we surveyed believe that fintechs will eventually take on an important role.

- Small but Growing. German fintech financing today includes around 150 companies, according to the only comprehensive report compiled on fintechs by the German Federal Ministry of Finance. Business volumes are forecast to reach about €30 billion by 2025 and €44 billion by 2035—up from nearly €1 billion in 2015. Business models can be classified into four major segments: financing, wealth management, payment transactions, and other models.

Fintechs have been active primarily in the business-to-consumer, startup, and venture capital arenas to date, but they have recently begun pushing into corporate banking as well. For example, online lenders from Germany and the UK have provided funds to both private individuals and businesses. Use cases have ranged from traditional growth financing to M&A, with loan volumes in most cases ranging from €0.1 million to €5 million structured as bullet loans or monthly annuity loans with maturities of up to 60 months. We have also seen fintechs piloting the use of blockchain technology for corporate financing. In addition, even established players are starting to push into the fully digital financing world. For instance, Landesbank Baden-Württemberg worked with Daimler to launch a one-year SSD using blockchain technology, providing Daimler with a total of around €100 million.

- A Few Hurdles. Before they can manage many large projects, fintechs need to professionalize their processes and structures. And midsize companies will need to be open to the possibility of using the digital range of services that fintechs offer. To help in these efforts, the German Association for Small and Medium-Sized Businesses and the FinTech Innovation Forum have developed an initiative with the purpose of “making fintech advantages useful for small and medium-sized businesses.” The initiative’s goal is to highlight the benefits of digital financial services and to help convince midsize companies of their practicality.

Nonetheless, fintechs will not be relevant for companies already in crisis, at least in the medium term, and especially if additional capital is needed. Once fintechs become more prevalent in the corporate financing arena, however, companies that borrow from them and then later experience financing difficulties will, of course, have to work with these fintechs in their refinancing.

At present, it is difficult to predict how a restructuring process would progress in such cases. Fintechs do not have the necessary structures and resources to handle active crisis settlement and are unlikely to build them, at least as long as the volumes are small and collateral is good. We assume that, in the event of default, fintechs will attempt to liquidate their collateral quickly and, if necessary, involve external service providers to handle such exposures.

SME bonds and mezzanine capital lose relevance as SSDs remain important. SME bonds and mezzanine capital (a hybrid instrument that falls between equity and debt) are declining in importance, while SSDs remain valuable. Although SSD issue volumes have declined recently due to some prominent troubled cases, SSDs that have already been issued will be part of many refinancing deals, given that the time to maturity can be as long as ten years.

SME bonds and mezzanine capital are declining in impor-tance, while SSDs remain valuable.

- SME bonds are problematic Confidence in the SME bond segment has been lost and is unlikely to be regained in the near future. While outstanding corporate bonds in Germany reached a new record at the end of 2017, with a total volume of €303 billion, this growth was propelled almost exclusively by large enterprises, and bond issuance by German midsize companies—€800 million in 2017—was relatively small.

The Stuttgart stock exchange created the Bondm segment for trading SME bonds in 2010 in an effort to provide smaller companies with access to the capital markets. Düsseldorf and Frankfurt followed suit shortly thereafter. After experiencing a short boom, however, numerous bankruptcies—such as that of the agricultural firm KTG Agrar and the wind farm developer Windreich—soon rocked the market. Only four years later, the Stuttgart stock exchange withdrew from the SME bond business, having posted a dismal performance, with around 60% of issuers either declaring bankruptcy or restructuring their bonds under the German Bonds Act.

Midsize companies in a crisis do not usually turn to bond issues because these companies cannot meet the requirements for a successful bond placement in the capital markets. But SME bonds will unavoidably become part of the refinancing process if a company that has already issued a bond falls into difficulty.

- Mezzanine capital has vanished. Mezzanine capital also has little relevance to private-company financing today. From 2004 to 2007, various banks created standard mezzanine programs, with terms of up to ten years. These programs pooled several mezzanine financing agreements by means of securitization and then sold them to institutional investors. While initially seen as attractive investments with strong yield opportunities, their reputation soon faded. When the financial crisis began in 2007, they could no longer be placed, and the last standard mezzanine program expired in 2014.

- SSDs stay relevant. SSDs have a long tradition in Germany, and midsize companies tend to consider them to be an attractive source of funding. They also represent a good financing alternative for companies with declining performance, given SSDs’ relatively low standards for creditworthiness, low documentation requirements, and a lack of follow-up obligations under capital markets law. Such companies can thereby gain access to institutional investors that they would not have been able to reach through traditional channels.

In 2017, a record volume of €29 billion—almost four times the volume in 2013—was issued in Germany. Sparkasse savings banks, Volksbank credit unions, and commercial banks are increasingly investing in SSDs, along with pension funds and insurance companies, as part of their search for alternative investment options.

Nonetheless, Moody’s forecast that the market would shrink in 2018, declining to the issue volume of 2015. In particular, two newsworthy setbacks have been suppressing demand. British construction group Carillion was forced to file for bankruptcy in early 2018, one year after issuing a €112 million SSD. In addition, because of a drawn-out accounting scandal, furniture retailer Steinhoff International is keeping holders of its SSD in constant fear of losing their investment. Investors are viewing these two cases as warning signs and are reminded of the fate of SME bonds and standard mezzanine programs, whose downfalls were also heralded by severe defaults.

Despite the decline, we expect SSD restructuring to play a prominent role in distressed situations because many companies have SSDs on their books. Our surveyed experts predict that SSD restructuring will be more complex than bond restructuring and, in some cases, take longer because the law does not define a relationship among SSD lenders. If a company experiences difficulties, therefore, it must meet with each lender individually to gain its approval. We note that, while conflicts of interest are unavoidable, SSD lenders may choose to take an approach similar to that of bondholders and hire an agent to represent and facilitate agreement among them.

Shareholder financing remains key. Shareholder financing, including both capital increases and shareholder loans, plays a critical role in the German financing landscape. External financial backers consider shareholder contributions to be a positive sign and frequently use it as a basic prerequisite for providing further capital. In fact, when a crisis appears imminent, shareholders should first make as many concessions as possible to help the business; otherwise, other lenders are unlikely to consider any new loans or investments.

Shareholder financing plays a critical role in the German financing landscape.

Not surprisingly, nearly all of our respondents—more than 90%—assume that shareholder financing will remain important. This is particularly true for any restructuring effort. Shareholder contributions played a role in about one-third of our SME refinancing cases, making them the second most frequently used financing instrument.

Complexity Grows as the Landscape Shifts

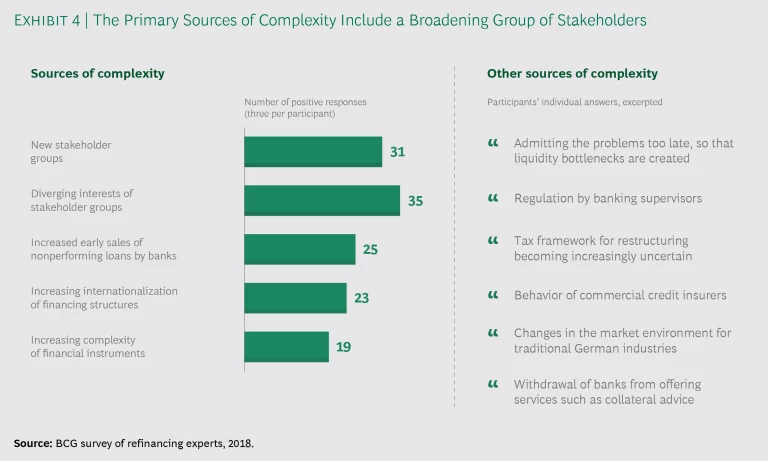

Given how the financial landscape for German midsize companies is changing, with new funding sources coming to the table and banks beginning to play a different role, the experts we surveyed cited several causes of growing complexity for businesses in a crisis. (See Exhibit 4.)

New Stakeholder Groups. When a company begins to experience difficulties, and restructuring cannot be avoided, numerous interests and stakeholder groups are affected. For German midsize companies, these groups historically have been the suppliers, employees, banks, and insurance companies that were interested in restoring the company’s competitiveness and solvency so that the bills could be paid.

But corporate financing has become increasingly complex and multinational in nature as businesses reach out to new investor groups and a wider variety of funding sources. As noted, these new financing sources must be included in creditor negotiations, with their representatives seated alongside traditional lenders. And the refinancing process is more difficult for corporate bonds and SSDs, for example, than it is for bank loans. Digital financial innovations will eventually complicate the process still further, and the ways they will affect the restructuring effort are uncertain.

Diverging Interests of Stakeholder Groups. Given that a more heterogeneous group of financiers naturally will have diverse concerns and expectations, it’s not surprising that more than half of the experts we surveyed consider the diverging interests of these new stakeholders to be a leading generator of restructuring complexity. The success of future restructuring efforts will therefore depend more than ever on striking a balance among the different interests.

Early Sales of Nonperforming Loans. More than half of our experts anticipate a further increase in bank sales of nonperforming loans. Refinancing situations may therefore arise in which a bank has already sold its exposure and is no longer under any pressure to provide fresh capital. Rather than dealing primarily with their original bank lenders, as in the past, companies in these situations will find themselves negotiating solely with new investors whose agendas may differ significantly from those of the old creditors.

Internationalization of Financing Structures. Like bond and SSD holders, many of the financiers that are becoming active in the market, including PE and PD funds and fintechs, are based outside of Germany. And the buyers of nonperforming loans are likely to be global investment banks and hedge funds. Not surprisingly, this growing internationalization will make refinancing during a crisis even more involved and will include more lawyers and advisers with international expertise.

Increasing Diversity of Financial Instruments. German midsize companies formerly had one or more traditional loan agreements with similar structures, content, and conditions. As the financing landscape changes, however, these companies must work with many different instruments, which automatically adds complexity, as does managing and restructuring those instruments.

Refinancing Success Factors in a Crisis

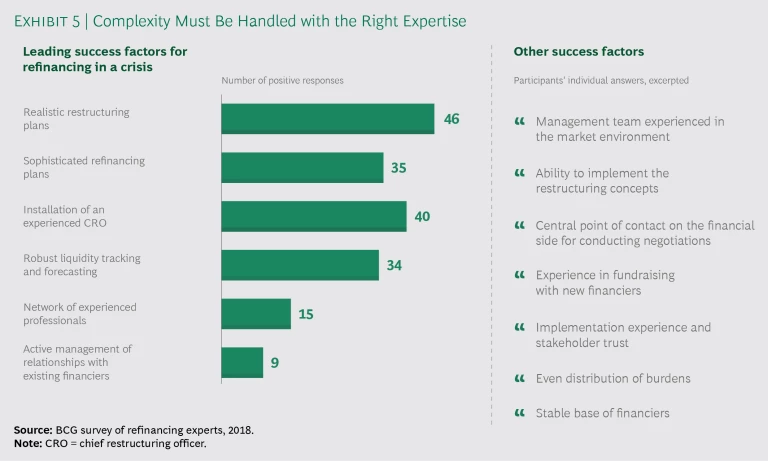

Obtaining corporate financing and simultaneously restructuring the business is a huge challenge during a crisis. In today’s shifting financial landscape, midsize companies will need to employ a number of success factors if they are to avoid jeopardizing the process. We offer the following, which we gleaned from our survey results, expert interviews, and cases. (See Exhibit 5.)

Well-Developed Restructuring and Refinancing Plans. Sophisticated and realistic restructuring and refinancing plans are among the most important success factors in a restructuring effort, according to our survey respondents. If these plans are not well prepared, all other restructuring attempts are destined to fail. Companies should work with all interest and stakeholder groups to agree on the plans early in the process, clarifying expectations and preparing their own accounting and other divisions to provide information rapidly when requested. In addition, they should implement advanced data analytics when possible to support the plans—for example, by improving sales forecasts and cost transparency.

A good plan plays two key roles: It serves as a strategic and operational blueprint that can steer the company onto a path for success. And it minimizes individual board members’ liability and recourse risks by providing clear documentation of the company’s current health and the way forward. The plan should cover all relevant dimensions of the restructuring, including market and competitive environment, current performance, the causes of the crisis, and the strategy for the future. It should include sound industry know-how as well as profound functional expertise. And given that a business group’s individual companies can be located in several countries, the plan should also bring together both global and local perspectives.

An Experienced CRO at the Helm. A restructuring plan is useless if it is not implemented consistently. Of our respondents, 63% consider the inclusion of an experienced chief restructuring officer (CRO) to be a key success factor. As members of the executive board, CROs are responsible for moving the restructuring process forward with confidence and assertiveness. In doing so, they free up management to run the day-to-day business. And in their role as neutral negotiators, they create agreement among all of the stakeholders, gain their cooperation, and push through the implementation of planned improvement measures. As decision makers working on the side of the company, CROs must also have a deep understanding of the numerous financing sources available and be able to curb complexity throughout the restructuring process.

Robust Liquidity Tracking and Forecasting. The chief obligation of a company’s management team, in addition to developing and implementing the restructuring plan, is to ensure the solvency of the business. The team must be sure that available liquidity, both current and projected, is transparent at all times, and it must create a detailed, reliable liquidity forecast that shows cash flows for the coming weeks and months. This forecast can help identify any potential liquidity bottlenecks so the company can introduce effective countermeasures. As noted, we also recommend the use of advanced data analytics to generate richer information flows, both to support the business and to provide the necessary information to lenders.

Network of Experienced Professionals. Companies in a crisis need experts who can quickly understand the causes of, and develop in-depth proposals for resolving, the issues. They must be able to select suitable measures, create a streamlined schedule of implementation, and ensure that all stakeholder groups are included in the process on an ongoing basis.

Not surprisingly, demand is growing for experts who have an in-depth understanding of the industry and the appropriate strategic and operational improvement measures at their disposal. Further, these experts must be able to work across borders and actively manage all of the individual sources of complexity, including the various funding sources and their divergent interests, the extreme time pressure typical in a refinancing effort, and the continually growing demand for information by lenders in response to new regulations.

Active Relationship Management. Companies in crisis must actively maintain relationships with all of the various stakeholders in the restructuring process and reach out to potential new investors early in the process. Both of these activities become more difficult as alternative sources of funding increase in relevance and as banks come under increasing pressure to exit troubled loans. Regular communication with these groups will have particular significance, given that each group will want to fight for its own claims and interests.