Trends reshaping the business environment during the past decade have created new opportunities for procurement to enhance a company’s overall performance. Supply markets and management have become more dynamic and complex as companies develop global supply chains and pursue growth opportunities in developing markets. What’s more, the risk of supply chain disruptions has increased as commodity prices and foreign exchange have become more volatile.

In this environment, even excellence in traditional core activities is no longer enough. Now procurement must be able to anticipate and address challenges in dynamic supply markets as well. To succeed, procurement executives will need to work closely with business partners to make decisions with a cross-functional, end-to-end perspective along the supply chain. To this end, many procurement functions now report directly to the CEO or CFO—a clear indication of their elevated strategic importance across the organization.

To fulfill their new mandate, procurement functions must develop and broadly apply a range of specialized skills that go beyond traditional cost management to materially improve the bottom line. Typically, the challenges they face include determining which capabilities to prioritize, as well as facilitating and managing cross-functional collaboration.

As leading procurement organizations have demonstrated, a structured approach to building capabilities is critical for success. Some companies that have established leading-edge procurement capabilities and addressed volatility and supply risks have improved their margins by more than five percentage points—a significant return on investment. Other benefits can accrue as well, such as developing more innovative supplier relationships, boosting growth rates in rapidly developing economies, and improving service capabilities.

For example, a major alloy producer interested in learning more about its products’ value in use involved the procurement team in discussions with customers. The team worked with the sales division and production managers to figure out how raw-material characteristics affect the production process downstream. Team members also developed and conveyed their insights on key supply markets and shared their knowledge of supply market innovations concerning the characteristics with the other parties in the discussion. As a result of this collaboration with customers, which took an end-to-end perspective on the business impact, the team was able to optimize the mix of input materials. This allowed for better material characteristics and a higher price in the end market. Procurement’s contribution played a significant role in increasing the value in use for customers while improving the alloy producer’s operating margins by up to 8 percent. (See “The Benefits of Developing Advanced Capabilities,” below.)

The Benefits of Developing Advanced Capabilities

The benefits of developing advanced procurement capabilities can take many forms and may be achieved across industries.

- Global Supply: Managing Risks. The procurement department of a major Asian automotive company played a vital role in ensuring business continuity following a major natural disaster. Procurement quickly assessed the industry’s supply chain, evaluated the status of global suppliers, and identified alternative supply sources. This helped the company to alleviate a critical supply shortage more quickly than expected and to achieve a faster recovery for its overall production process.

- Machinery: Achieving Design-to-Cost and Scale Benefits from Platform Design. A high-tech company whose material costs accounted for 60 percent of its product costs aimed to reach competitor benchmarks for material efficiency and cost levels. The company hoped to improve its cost structure by more than 20 percent through economies of scale and by achieving greater uniformity in its supply chain. An important element of this turnaround agenda was developing a more standardized architecture for the company’s portfolio of diverse products, which were manufactured at global production sites. Procurement’s involvement was essential. It actively contributed to the company’s design-to-cost initiatives and product-architecture-standardization efforts and managed the effort to standardize the supplier portfolio for key commodities at all global production sites.

- Consumer Goods: Applying Advanced Analytics to Surpass Targets for Cost Savings. A consumer products company hoped to cut costs so it could reach profitability targets within a year and free up money to invest in marketing. To help the company meet its goals, procurement introduced advanced analytics and scenarios analyses, as well as detailed cost models. To ensure that all regions and businesses benefited from these new tools, the function developed a global training program that was rolled out to more than 200 employees. Ultimately, the company achieved $200 million in annual run-rate savings above the original target of $50 million. When the head of strategy asked what drove the incremental savings, he was advised that procurement’s introduction of new tools and approaches had played a critical role in both generating new ideas and convincing stakeholders to proceed with the cost-savings initiatives.

- Mineral Resources: Reducing Maintenance Costs by Aligning Contracts with Business Objectives. A major mineral-resources company reduced costs by reviewing targets for equipment availability and maintenance in light of new insights into operating requirements. For example, a cross-functional negotiation team finalizing maintenance contracts with equipment suppliers found that a much lower guaranteed uptime for production equipment would be sufficient for meeting midterm business objectives. By reducing guaranteed uptime by 15 percentage points, the company was able to significantly decrease the annual contract costs for maintenance and express delivery services.

Advanced Capabilities for Capturing Strategic Value

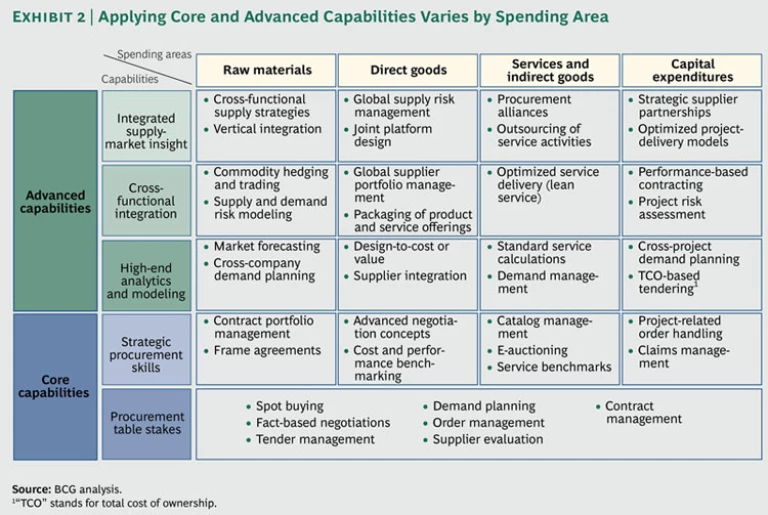

Companies certainly expect procurement to fulfill its traditional role, which includes supplying needed goods and services and managing spending categories and key supplier relationships. However, companies also expect procurement to develop enhanced capabilities and even to seek and maintain a competitive advantage—and that requires a new approach to building and applying skills. Training programs should expand their focus to specifically address advanced capabilities that capture strategic value in critical spending areas. (See Exhibit 1.) Because procurement is a hub for interactions between other functions and external partners, it is equally important to develop team members’ interpersonal skills when building capabilities.

Advanced capabilities typically fall into one of three categories: high-end analytics and modeling, cross-functional integration, and an integrated supply-market perspective. High-end analytics and modeling can enhance decision making by providing, for example, a clearer view of overall life-cycle costs to evaluate the total cost of ownership for complex investments. They may also allow for a more refined market perspective based on market scenario forecasts and demand modeling for specific commodity markets. In addition, developing sophisticated “should cost” models can provide critical information for negotiating with, and managing, suppliers.

Cross-functional integration seeks to improve close collaboration with business partners and even suppliers. For example, cross-functional design-to-cost teams can evaluate and optimize product and service requirements, and cross-functional governance mechanisms can help implement supply strategies across organizational units.

An integrated supply-market perspective provides a broad view of the supply chain, which is useful for developing sourcing strategies. For example, a company can identify opportunities for participating in procurement alliances to reap the benefits of scale. Integrated supply management may also entail a fundamental review of the company’s current positioning along the value chain, such as the level of vertical integration or the scope of activities that are outsourced.

These capabilities are applied in many different ways in practice, and a company’s focus with regard to each type of capability will depend on its critical spending areas. (See Exhibit 2.)

An Integrated Approach to Building Capabilities

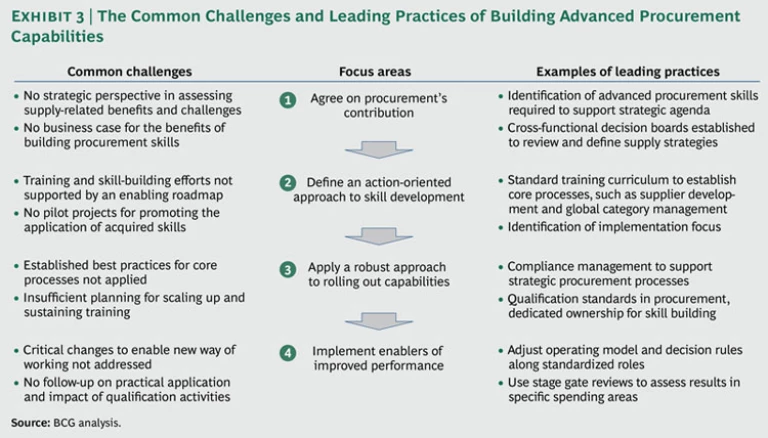

We have found that the best way for companies to build capabilities is to apply an integrated approach that addresses four focus areas: agreeing on procurement’s value contribution, defining an action-oriented approach to skill development, applying a robust approach to rolling out capabilities, and implementing enablers of improved performance. (See Exhibit 3.)

Agree on Procurement’s Value Contribution

Before an organization designs a capability-building program, procurement leaders and top management should agree on which skills the program will seek to build. In a well-designed program, the stakeholders choose capabilities that are likely to produce tangible benefits, such as reducing costs. They also figure out the potential benefits of applying enhanced capabilities to overcome supply-related challenges.

Leading companies have created decision boards with representatives from procurement and other functions. The boards identify which advanced capabilities will be required and which functions should participate in the capability-building program. They also review plans using a business case framework that helps procurement to prioritize its capability building according to the pros and cons of each approach.

A company’s strategic priorities for procurement—and the skills it must build to pursue them—will, of course, depend on the company’s industry and specific objectives. Several examples illustrate the range of possibilities:

- In process industries, such as chemicals, procurement must have a deep understanding of chemistry and the dynamics of the supply chain through several levels. For example, one major producer of specialty chemicals needed to secure key sources of supply. The procurement team initiated a program in collaboration with the strategic-planning function to identify new sources of supply and to manage critical supply relationships. The team also developed an improved forecasting model that enhanced the company’s ability to anticipate price changes and proactively adjust prices.

- A technology conglomerate with production facilities all over the world aimed to establish global standards for managing its supply base. The company initiated a program that sought to reduce the number of supplier relationships while improving integration with partners in areas such as quality control and joint supply-chain planning. It also implemented new processes for making decisions about existing suppliers and contracting with new suppliers.

- Through increased cross-functional collaboration, a global metals producer developed a comprehensive business perspective on the company’s procurement of raw materials and thereby was able to significantly increase its margins. The company’s procurement and sales departments had been meeting their respective cost and revenue objectives. But profitability was under pressure, and raising margins by changing product specifications would have meant buying more expensive, higher-grade raw material. To adapt procurement practices, top management adjusted performance targets to reflect the new focus on margin improvement. Management also established cross-functional teams charged with resolving conflicting requirements concerning cost and revenue management and identifying the impact of decisions on product margins.

In addition to periodically reaffirming priorities, procurement must communicate regularly with line management and key stakeholders on supply-related issues. The procurement function of a large steel manufacturer, for example, had successfully managed supplier risks at existing production sites and maintained a joint demand forecast with production managers. During a major expansion project, however, the departments responsible for managing a new plant did not involve the procurement team in the early stages of critical planning efforts, such as forecasting demand and qualifying the supplier base. As a result, the supplier base was not ready to serve the new plant early enough, and the plant’s production ramp-up was delayed by several months. To prevent this from happening again, the company initiated a training program and established a standardized operating model that ensures continuous collaboration among all the functions involved in core procurement processes.

Define an Action-Oriented Approach to Skill Development

To translate their strategic objectives for capability building into bottom-line impact, leading companies ensure that their investments in training are tightly linked to procurement’s day-to-day operations. They accomplish this by designing capability-building programs that combine classroom instruction with on-the-job deployment of new skills.

When designing a training program, organizations should consider how participants will apply the lessons they have learned to their daily work. To ensure that those lessons become part of the normal course of business, the training curriculum should align with the company’s core procurement processes, such as category strategy definition, the source-to-contract process, and supplier development.

A roadmap for capability building should identify up front the opportunities for directly applying elements of the training agenda in pilot initiatives.

The company should ask cross-functional teams to identify the scope of the pilots to ensure that the advanced approaches are tested in appropriate settings. Team members from other functions—such as engineering, quality management, and logistics—should also participate in the program, so that cross-functional collaboration is developed throughout the organization.

Apply a Robust Approach to Rolling Out Capabilities

Following a successful pilot, leading organizations facilitate the rollout of the training program by asking members of the initial team to share best practices with new participants. They also develop approaches to ensure that best practices are applied in daily operations. These approaches often include introducing qualification standards for successfully completing the training program and designating someone to be accountable for its results.

When rolling out a capability-building program to the full team of procurement professionals, some companies have achieved success by establishing a new organizational entity to lead the effort. (See “Building Capabilities with a Procurement Academy,” below.)

Building Capabilities with a Procurement Academy

A mining company based in an emerging market established a “procurement academy” as a key element of its ongoing training program. The company had operations in multiple locations and was transitioning to a centralized procurement model to enhance scale benefits and to better define the scope of procurement activities. A successful transition required addressing several change-management challenges.

Because the procurement division had been following a decentralized model, transactions had been managed at only the local level. Since local management teams had limited exposure to other functional areas, moving to a centralized structure offered significant opportunities. To enhance value from procurement, the company sought to develop standards for effective category management, with an emphasis on employing concepts and approaches such as total cost of ownership, the use of frame contracts, and proactive supplier management.

Given its starting position, the organization had to implement change management simultaneously across different businesses and in diverse locations in addition to building capability on functional procurement topics. The company established its procurement academy to ensure an integrated approach and action-oriented framework for this capability-building program. To bring together a cross-functional set of participants, the academy combined classroom-based instruction on technical expertise with on-the-job coaching on applying the new routines and approaches. (See the exhibit.)

The classroom instruction introduced participants to concepts such as category management and supplier risk management, which were deployed in the organization shortly thereafter. The on-the-job projects revealed the benefits of cross-functional collaboration and exposed participants to the needs and challenges of different functions. The first wave of participants in the academy also produced a talented set of employees who went on to form the core of the procurement function and to lead future steps of the capability-development process.

In addition, the procurement academy helped the organization gain a more highly skilled workforce by teaching the participants functional capabilities and showing them how to use those capabilities on the job. The action-oriented learning approach helped to set new standards for cross-functional collaboration by identifying best practices and establishing joint organizational routines and approaches.

The academy engendered broader and deeper stakeholder engagement in the procurement function and helped the company boost the gains from its cost-reduction program by 10 percent.

Companies should make sure not to overlook the importance of improving overall compliance with best practices related to core capabilities. For spending areas in which common best practices in supply management have emerged (such as many indirect expenditure categories), making sure to establish a solid foundation of core capabilities can have a stronger impact on the bottom line than establishing complex cross-functional approaches.

Implement Enablers of Improved Performance

To ensure that advanced capabilities are deployed effectively, leading companies implement critical enablers of improved performance, such as making adjustments to the operating model or elevating the level of talent in the organization.

Making adjustments to the operating model, such as establishing cross-functional category boards to monitor decisions and review progress throughout the sourcing process, can improve cross-functional collaboration and decision making. During pilots, companies can evaluate potential adjustments to the operating model for specific spending areas by considering the following:

- Does the organization’s current operating model strike the right balance between local execution and the centralized or coordinated definition of category strategies?

- Are decision-making processes and decision rights consistent and clearly understood throughout the organization?

- Are effective platforms, such as cross-functional design-to-cost teams and decision boards, in place to promote collaboration across functions and among global teams?

- Do the existing tools and methods support effective management of spending and strategic sources?

- Are performance metrics aligned with strategic objectives to promote compliance with identified standards?

- Is a robust IT infrastructure in place to support advanced capabilities and cross-functional collaboration?

Elevating the level of talent in an organization also helps to achieve procurement’s strategic ambitions. Leading companies develop attractive career paths and offer incentives when hiring, developing, and retaining top talent.

For example, a large national oil company sought to enhance its procurement capabilities to better manage volatility in the commodity and supplier markets so that it could maintain profitable growth. The organization also hoped to reduce costs and improve its management of an increasingly complex supply chain, from crude-oil sourcing to supplying fuel at filling stations. The company determined that its current model of allowing business units to conduct all transactional purchasing would impede these goals. So it opted to transition to a central procurement function reporting directly to the CEO and applied a talent management strategy to enhance the attractiveness of a career in procurement.

To emphasize the importance of procurement, the company staffed the department with some of the organization’s best performers, a number of whom had only limited procurement experience. The new team formed a nucleus that attracted further talent and made working in procurement a desirable step in the career path for top performers.

Leading companies also seamlessly integrate capability building and performance management. For example, they use a stage gate process to track and validate the category teams’ intermediate results, thereby ensuring compliance with the company’s category strategy process. At predetermined points, key members of the leadership team coach the category teams responsible for developing the supply strategy and review their progress. The review assesses each category team’s ambition and strategic focus, and determines how well it is developing and executing the category strategy.

How to Make It Happen: Capability Building in Practice

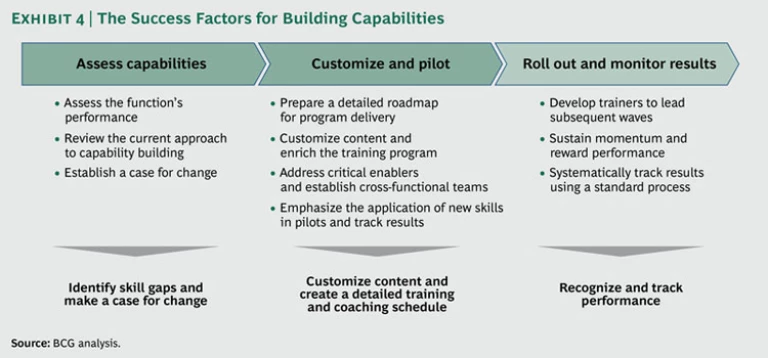

Companies can apply a set of ten practices throughout their capability-building programs to promote success. Those practices are critical across the three phases of a capability-building program—assessment, the customization and piloting of initiatives and tools, and rollout. (See Exhibit 4.)

Assess Current Capabilities

An organization should design its capability-building program after evaluating its procurement function’s performance and skills and identifying the expected benefits of deploying advanced capabilities.

Assess the function’s performance. A company should start by establishing a baseline for procurement’s current performance. To compare the function’s skills with best practices, the organization should gather feedback from the procurement staff (including a self-assessment and a prioritization of potential training modules) and from internal customers. The results can help define the capability-building program’s focus and reveal the potential value of enhanced procurement capabilities.

Review the current approach to capability building. The organization should review its current approach to capability building and deployment. This includes analyzing the roadblocks to applying best practices—such as a lack of effective cross-functional forums to drive the alignment of category strategies and inadequate performance management.

Establish a case for change. To justify an investment in strategic procurement capabilities, the company can use the assessment’s findings to demonstrate the need for change and show how specific capabilities will add value within a spending area. Leading companies establish baselines for spending and performance using three-year targets for procurement savings and then estimate the resource costs of the capability-building program. Individual business cases for particular spending areas can help to establish the near-term benefits of investments in specific skills and resources and to track the program’s performance as it is rolled out.

Customize and Pilot the Approach

In a second phase, the company customizes the elements of the capability-building program and pilots it.

Prepare a detailed roadmap for program delivery. To guide the multiyear program and transformation, companies need to implement an enabling roadmap that capability-building activities should follow. This is particularly critical when organizations, such as successful players from emerging markets, set ambitious targets to achieve their aspirations for best-in-class procurement capabilities. The roadmap identifies important intermediate steps and milestones along the journey, as well as the benefits that are expected to accrue from the effort. It also defines the program’s focus and highlights the interdependencies in multiple work streams and spending areas. The following are common elements of such a roadmap:

- A curriculum and specific modules for classroom training and coaching

- A detailed plan for training teams during the pilot and in subsequent waves

- Adjustments to the operating model, if required

A detailed plan for building and implementing advanced capabilities, such as the preparation of cross-functional strategies

Customize content and enrich the training program. Demonstrating a training program’s success in customizing best practices to a company’s specific situation helps gain acceptance for the program. Leading companies emphasize the development of successful initiatives in the pilot phase of the program to gain support for the implementation. The training program should also try to use a variety of instructional formats, including e-learning, and invite internal or external experts from other functions to lead some of the sessions.

Establish cross-functional teams. The procurement team should meet with teams from other functions and business units—ideally for the duration of the program—to foster an increased understanding of roles, to share ideas and challenges, and to improve teamwork. These teams should pilot performance measures, changes to the governance model, and the deployment of new collaboration approaches. For example, members of a cross-functional team could collaborate on reengineering a component or designing a product. The pilot teams provide valuable feedback that the organization can use to more effectively make the proposed changes. This gives the participants an opportunity to immerse themselves in the new way of working and to understand the benefits of doing so.

Emphasize the application of new skills in pilots and track results. During the program, coaches should support cross-functional teams in implementing major procurement projects that require applying the acquired skills. The coaches should meet with teams regularly to review results and facilitate the practical application of lessons in the pilot projects. Participants should then identify areas in their day-to-day work where they can use the lessons they learned during the pilots.

Roll Out the Program and Monitor Results

When the pilot phase is complete, the company can roll out the program to the entire organization, monitoring progress and assessing the results.

Develop trainers to lead subsequent waves. Larger organizations should roll out their training programs in several waves and apply capability levels and standards, similar to those in Six Sigma programs, to qualify a larger group of trainers. Typically, employees who have successfully completed the initial waves become trainers for subsequent waves.

Sustain momentum and reward performance. Top management can help highlight a training program’s importance by rewarding extraordinary performance and touting successful participants.

Systematically track results using a standard process. Stage gate reviews should be an integral part of the rollout phase. In addition to ensuring that ideas from outside the core team are applied in developing the category strategy, the review process can be used to support on-the-job training and assure that the new procurement capabilities are being applied.

Getting Started

As companies chart a new path for procurement and face revised expectations in today’s volatile economic environment, assessing ongoing capability-building activities is critical. To evaluate the effectiveness of their current approach to capability building and identify the roadblocks to broader application, executives can consider their responses to a series of pointed questions. (See “Is Procurement Applying Best Practices in Capability Building?,” below.)

Is Procurement Applying Best Practices in Capability Building?

Procurement executives can use the following questions to evaluate the current status of their capability-building activities. The answers may reveal opportunities for significant improvement in their approach.

Setting Expectations for Procurement

- Do you have regular interactions with business functions regarding procurement’s strategic role?

- Are the expectations for procurement’s contributions to the company’s agenda and bottom line well defined?

Establishing a Case for Change

- Have you prioritized the benefits of improved performance by procurement?

- Have you identified the essential skills to be developed and assessed the effort required to build them?

Prioritizing Category Groups

- Have you prioritized spending categories based on their strategic importance?

- Have you identified which procurement activities, in which major categories, your capability-building program should address?

Creating a Company-Specific Knowledge Base

- Do you have a customized strategic-procurement manual to support training new members of the procurement team?

- Have you established a common approach for core procurement processes?

Defining the Curriculum and New Skills

- Have you established a dedicated training curriculum for enhancing procurement capabilities?

- Have you identified critical capabilities for selected spending areas—for example, evaluating the total cost of ownership?

Promoting Robust Deployment and Compliance

- Do you support the practical application of new capabilities in pilot projects?

- Do you have a clear process for tracking the rollout of capabilities? Do you use stage gates with real-time feedback?

Defining Individual Roles and Expectations

- Are roles, competencies, and expected capabilities defined for individual buyers?

- Do you maintain an up-to-date understanding of procurement teams’ capabilities and training needs?

Managing Performance

- Do you manage performance effectively and recognize successful qualification?

- Do you follow up on the practical application of skills learned through the training programs and the impact they have had on the organization?

Companies that want to improve their procurement function should create more effective cross-functional linkages and establish a program that builds advanced capabilities and extends across the organization. They should also develop the ability to deploy these capabilities broadly in the company’s context and make procurement roles attractive, important steps in a career path. Organizations that do so successfully will ensure that their procurement functions are well prepared to apply the new skills that enable superior cost performance and build competitive advantage.