Africa is growing larger on the corporate map. Mostly ignored by multinationals since the 1980s, the continent is now receiving their attention and investment, and for good reason. Growth rates are rising, and many long-running wars and conflicts are giving way to democracy and bureaucratic competence. Infrastructure and connectivity are improving.

As competition for growth in Southeast Asia and Latin America gets fiercer, companies are seeking the next frontier market. They have understandably trained their sights on Africa, whose growth trajectory has been the steepest in the world over the past decade and is likely to remain so into the future, with forecasts projecting 6 percent annual increases over the next decade. Emblems of optimism, progress, and consumerism abound in the form of smartphones, paved roads, bank accounts, and peaceful transitions of power. Over the past two years, dozens of media and analyst reports have increased awareness of Africa’s rise and the opportunity for private investors and multinationals.

Awareness of the Africa opportunity is one thing. Winning in Africa is another. The continent remains a dizzying collection of emerging markets, each with its own unique business environment, risk profile, and potential. Success in places like China or India will not necessarily translate into success in Africa. Many companies have been operating in Africa for decades and have learned the hard lessons that await newcomers. Unilever, Coca-Cola, Nokia, and a few others generate up to 10 percent of their sales in Africa. But companies just starting their Africa journey in earnest do not necessarily know how much to expect, where to start, and how to win.

In 2000, The Economist declared Africa “hopeless”—the conventional view at the time. In 2011, the magazine revised that assessment to “rising” and in March 2013 to “aspiring.” In fact, the seeds of Africa’s resurgence were already planted in 2000 but had not yet borne fruit. Today the fruit is ripening.

Economic Africa

Many of today’s executives came of age in the 1980s and 1990s, when media reports about Africa focused on the devastation wrought by drought, communicable diseases, and poverty. Unless they worked for a nongovernmental organization (NGO) or relief organization, the world’s business leaders did not include Africa on their itinerary or agenda.

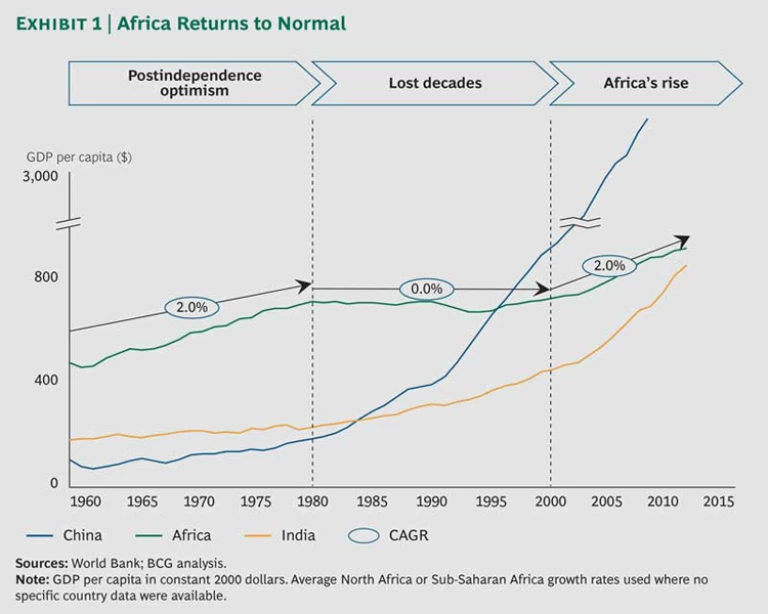

Those years represented Africa’s “lost decades.” Fortunately, they are unrepresentative of the continent’s past and future. Africa has always been rich in natural resources and produced bountiful supplies of food. In fact, Africa entered the postcolonial era with a running start over many other emerging markets and held onto that lead for at least 20 years. By 1980, Africa’s annual per capita GDP of $708 was nearly three times the size of India’s $230 and almost four times the size of China’s $186 (in constant 2000 dollars).

Africa lost this lead for reasons both within and outside of its control. Among other factors, weak governance, autocratic leaders, ethnic conflict, and widespread nationalization of private enterprises stifled entrepreneurial zeal and slowed forward momentum. When food and commodity prices plunged in the late 1970s and 1980s, so too did many African economies. Africa’s small farms were less able to withstand the decline in prices than larger, more efficient, government-subsidized operations elsewhere. Despite high population growth, the continent’s share of global agricultural production dropped. A similar thing happened to Africa’s natural-resource industries, which remained focused on upstream extraction rather than local manufacturing and value addition. This left them exposed to low commodity prices in the 1980s and 1990s.

As a result of these developments, capital and the best and the brightest fled the continent, and foreign investment dried up. Debt service as a percentage of GDP rose from less than 2 percent in the mid-1970s to more than 6 percent by 1985. Inbound migration during the 1960s morphed into outbound migration by the 1980s. Per capita GDP stayed flat during the lost decades. By 1996, measured by per capita GDP, China had surpassed Africa.

By the end of the lost decades, Africa’s postcolonial hope and promise had vanished. Small groups of elites controlled both political and economic power in many nations, and nearly all of them struggled to meet the basic health, educational, infrastructure, and environmental needs of their people. Africa was a marginal player in the global economy.

A Trading-Post Economy

During the lost decades, many multinationals retreated entirely from Africa or scaled back their business. A select group of consumer goods and natural-resource companies remained, served by another small group of infrastructure, industrial equipment, and logistics providers.

Consumer companies mostly focused on the top of the market. They sold Western goods, largely without modification or local adaptation, to elites and expatriates. They minimized their investment in Africa by building their business model around low volume and high margins and by shipping goods into Africa rather than sourcing and manufacturing locally. They tended to send expats—and not necessarily the best ones—to run their local businesses.

Natural-resource multinationals also tended to follow a strategy that minimized their involvement and presence on the continent. They extracted metals, minerals, and oil to sell to customers outside of Africa, ignoring domestic markets. Most of their senior managers were expats, and they hired local employees for low-skilled work that was often dangerous. Rather than create value on the continent by, say, cutting and finishing diamonds, they shipped raw resources abroad.

Even prior to the lost decades, Africa was a distant outpost that often did not receive adequate management attention, investment, or organizational support. While production capabilities and a consumer class began to emerge in other emerging markets, Africa remained a trading post. Finished goods arrived to satisfy a happy few in selected ports and urban centers. Raw materials—and most of the value generated from doing business in Africa—left the continent. This was the state of play at the turn of the century.

A New Dawn

Fast forward to this decade. Since 2000, Africa’s GDP has been growing 2 to 3 percentage points faster than global GDP, helping the continent regain lost ground. Annual GDP growth is now starting to approach postcolonial levels. (See Exhibit 1.)

Foreign companies are returning and moving in. In 2013, Barclays Bank increased its stake in Absa Group of South Africa and rebranded the entity as Barclays Africa Group. Philips, which had reduced its presence in Africa from 35 nations to just 5 during the lost decades, has been expanding across the continent by building its direct presence in key markets like Kenya and Nigeria and by starting to design products tailored for the African market.

The consumer giants that elected to stay in Africa are experiencing double-digit growth. Samsung, for example, has set a goal of $10 billion in African sales by 2015. The company is also committed to training 10,000 African engineers and technicians by 2015 in order to develop the capabilities required to succeed.

Meanwhile, many large companies from other emerging markets have stamped their ambition on Africa. Chinese telecom-equipment suppliers Huawei and ZTE both have a presence in more than 50 African nations and generate more than 10 percent of their revenues from the continent. India’s Bajaj Boxer is the best-selling motorcycle in Africa, which accounts for more than 40 percent of Bajaj’s exports.

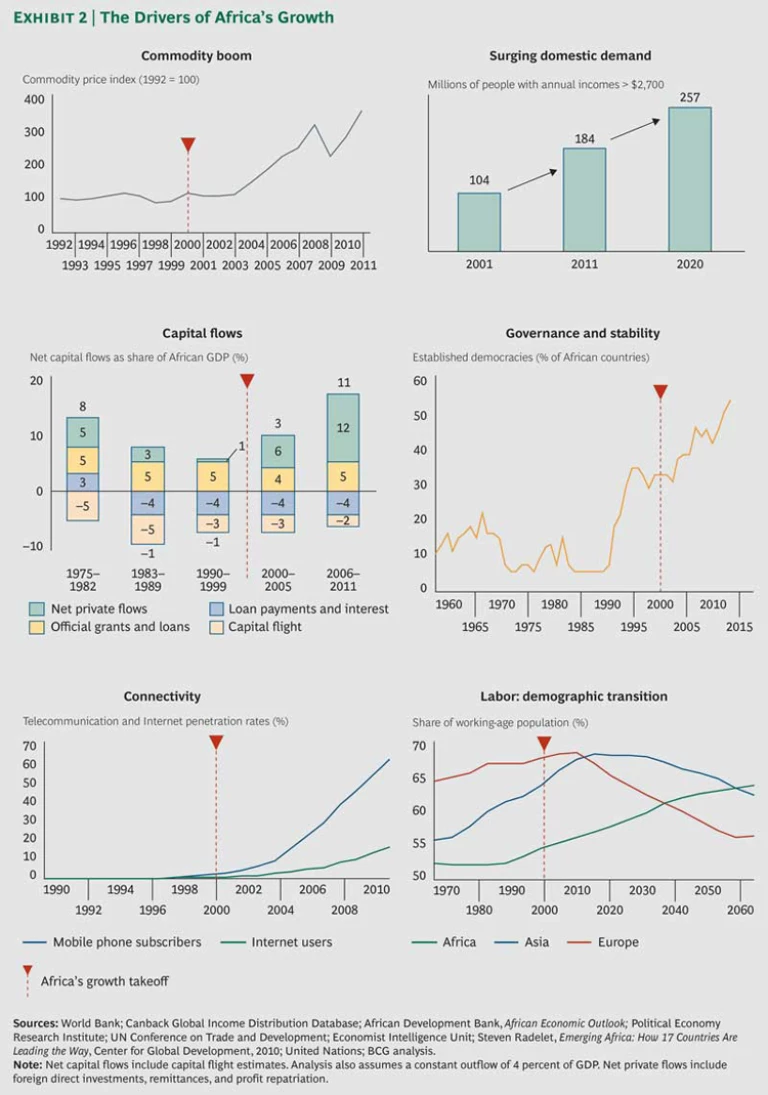

Skeptics like to dismiss Africa’s resurgence as a reflection of rising commodity prices. In fact, Africa started growing before the global run-up in commodity prices. Further, economies not dependent on oil or mining revenues, such as Ethiopia, Ghana, Morocco, and Kenya, have also been growing. At least five factors in addition to commodity prices have powered Africa’s rebirth. (See Exhibit 2.)

Capital Flows. Capital flight had a draining effect on Africa during the 1980s and ‘90s, with nearly as much money flowing out of the continent as arriving in the form of investment, aid, and debt relief. During the mid- to late 1980s and the 1990s, the equivalent of 1 percent of Africa’s GDP left the continent. Now the equivalent of 11 percent of GDP is flowing into the continent.

The tide began to turn at the end of the 1990s. Contributing to the reversal were improvements in the economic and political climate as well as the 1996 debt-relief plan for poor nations instituted by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. Since 2007, annual inflows of foreign direct investment have reached at least $45 billion annually, compared with less than $10 billion annually during the lost decades. The investments are coming from the West but also increasingly from China, India, and Brazil.

In 2012, the Economist Intelligence Unit interviewed 158 large money managers about their planned African investments over the next five years. It found that fewer than one in ten money managers are investing more than 3 percent of assets under management in Africa today, while nearly eight out of ten will be doing so in five years.

At the same time, Africans living abroad are sending money back home. In most years, these remittances are nearly equal in size to foreign direct investments, and in some years they exceed them. Finally, while savings rates in Africa still lag those in China and India, they have risen modestly and now exceed those of the U.S. and the European Union. In 2010, African savings exceeded $170 billion, up from $109 billion in 2000.

Labor. While most of the developed world is growing older, Africa will have a young workforce for decades to come. Shortly after 2030, more than 60 percent of Africans will be of working age. By 2040, Africa will have a larger working-age population than China or India, and by 2060, it will have a larger percentage of people of working age than any other continent.

Africa will reap the benefits of this so-called demographic dividend about ten years after Asia does. The benefits are multifaceted. The continent’s large working-age population will supply labor to companies but also free up capital that, in older economies, is being soaked up by the elderly in the form of social spending. In coming decades, a smaller share of Africans will be enrolled in school as more and more people enter the workforce. This transition will also lessen the social-spending burden.

Africa’s workforce is not just young and growing but also better educated than ever before. In Angola, for example, the number of students enrolled in primary school has tripled since 2001, and the enrollment rate has hit 80 percent. The share of young people of secondary-school age who are in school rose to 40 percent in 2010 from just 25 percent in 2000. Across the continent, adult literacy rose from 57 to 63 percent during the same period.

Connectivity. The rapid rise in mobile and Internet connectivity in Africa is helping the continent’s economies modernize. Unshackled by legacy infrastructure or embedded commercial interests, they are leapfrogging their developed-market counterparts by taking advantage of the latest waves of innovation, leveraging technology to address their most urgent development needs.

Africa is the fastest-growing mobile phone market in the world. Penetration jumped from less than 2 percent in 2000 to more than 60 percent in 2011. Between 2012 and 2016, mobile connections in Africa are projected to grow at an annual rate of 21 percent. Mobile phones are increasingly helping Africans run businesses; find jobs; pay bills; learn, share, and connect; and deposit, withdraw, and transfer money. East African farmers share best practices in order to increase crop yields, and a not-for-profit organization in Ghana is using an SMS platform to fight the spread of counterfeit medication. Internet usage is growing, too, albeit less quickly. Google is working to make the Internet local by providing translation for many of the continent’s more than 2,000 languages.

Mobile and Internet access has had a greater effect on productivity and economic growth than elsewhere because the continent started from such a small base of fixed-line usage. For example, one-third of Kenya’s GDP now flows through the M-Pesa mobile-payments systems created by Safaricom, a telecom operator. Internet access has also been instrumental in the spread of democracy and greater government openness.

At the same time, African transportation and utility networks are also improving. Private-sector infrastructure investments nearly tripled between 2000 and 2010, and electricity generation has nearly doubled. The African Union’s Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa, launched in 2010, is prioritizing a series of ambitious infrastructure-development projects for the continent.

Governance and Stability. Recent events in a few countries notwithstanding, Africa is a less risky and more predictable place to do business as the continent increasingly benefits from peaceful political transitions. In 2011, for the first time in history, a majority of African nations were governed by democratically elected leaders. Between 1991 and 1995, Africa endured 35 coups and attempted coups. Between 2006 and 2010, that number had dropped to 14.

Free elections are on the rise. While elections do not ensure robust participatory democracy, they are a step in the right direction. “In the past decade or so, Angolans stopped fighting after half a million people died, and Chad lapsed into peace after four civil wars,” The Economist wrote in a recent cover story. This reduction in violence has made investors and companies more willing to invest.

Governments are not just becoming more democratic. They are also becoming more competent and more oriented toward the private sector. A number of today’s African leaders and their cabinets have private- and development-sector experience. Policies such as privatization are increasingly driven by dispassionate analysis and logic.

Surging Domestic Demand

These forces have promoted the development of more diversified and sustainable national economies and an emerging consumer class. Between 2001 and 2011, the number of Africans with more than $2,700 in annual income—the threshold for discretionary spending in emerging markets—expanded from 104 million to 184 million. By 2017, that number will likely have risen to 257 million. These consumers tend to be forward looking, fascinated by technology, and enamored of brands.

In fact, 88 percent of Africans are optimistic about the future, compared with 72 percent in China, India, and Brazil and 48 percent in mature economies, according to BCG’s survey of 10,000 consumers in eight African countries. (See “2013 Africa Consumer Sentiment Survey,” below.) According to the same survey, 47 percent of African consumers aspire to “trading up” in mobile electronics. Two-thirds reported that brands reflect their identity, values, and sense of belonging, compared with just 34 percent of Chinese, Indian, and Brazilian respondents and only 24 percent of respondents in mature markets.

2013 AFRICA CONSUMER SENTIMENT SURVEY

For more than ten years, BCG has conducted an annual Global Consumer Sentiment Survey to gather information on consumer behaviors and trends across many countries. In 2013, for the first time, BCG added several African countries to the survey, enabling comparisons across the continent and with other emerging markets, such as China, India, and Brazil, as well as with mature markets. Altogether, the global survey reached 40,000 consumers in 25 countries and was conducted in 20 languages.

In Africa, we surveyed nearly 10,000 urban consumers in eight countries: Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa. Respondents represented a mix of consumers of different ages and different income and education levels. The survey explored topics related to income, spending, and budgeting; technology, mobile, and Internet usage; preferred retail-shopping locations; and banking habits.

Additionally, the survey assessed planned expenditures, trading up and down, brand preferences, and shopping behaviors in 20 product categories: automobiles; baby and toddler products; beauty care; beer; breakfast cereals and foods; chocolate and candy; clothing, footwear, and accessories; coffee and tea; consumer electronics; hair care products; health care; home appliances; insurance; mobile phones and devices; packaged food; restaurants and out-of-home eating; snacks; soft drinks and other nonalcoholic beverages; spirits and other alcoholic beverages; and wine.

Furthermore, 40 percent of Africans live in cities—compared with 30 percent in India. Since city dwellers spend more than rural residents, a wide range of industries are expected to benefit from urbanization.

These trends suggest that a sizable portion of Africa’s population will soon be generating the discretionary income required to purchase more than just the bare necessities.

But the job is not yet done. Infrastructure still needs to be built. Corruption and autocracy have not yet been eliminated. Not all public leaders have embraced free enterprise. And NGOs and relief agencies have plenty of work left to do. Still, Africa has a stronger economic foundation than ever before and is better able to withstand commodity shocks and other external jolts.

It Takes an Ecosystem

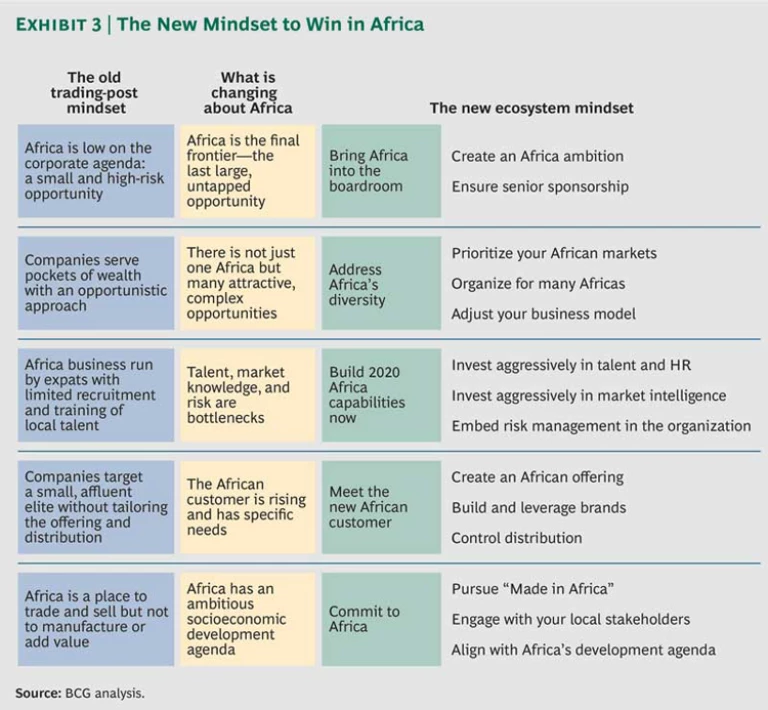

Companies have a great opportunity to benefit from Africa’s rebirth by conducting their business on the continent in a new way. They must abandon the old model of shipping in finished goods and shipping out resources and profits. Instead, they must prepare to actively engage and commit to a rapidly maturing continent. In the words of former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, businesses need to craft “sustainable partnerships in Africa that add value rather than extract it.” They must treat Africa as an ecosystem, not just a trading post.

Five African Realities

Africa is a demanding place to do business, requiring more of companies than other markets. It will take years for most companies to build African businesses comparable in size to their operations in China, India, and other emerging markets, where they have been operating for decades. They need to make the right investments at the right moment and with the right approach. Priorities, timing, and effectiveness are critical.

Fortunately, companies do not need to reinvent the wheel in Africa, and many of the lessons they have learned in other regions will be transferable. But companies that want to win on the continent will need to modify their approach to address at least five African realities:

- Africa is the final frontier. Africa is the last sizable area of untapped growth in the global economy. Its late economic emergence and challenging business environment mean that today there is less competition than in other markets, but that will not last. Despite the operational challenges, the time to enter Africa is now. But to succeed, companies will need to bring Africa into the boardroom.

- There is not just one Africa. The continent is a collection of different markets. Clusters of African countries share language, culture, borders, and trade and financial agreements, but they all require vastly different approaches to strategy, organization, and business. Companies need to address Africa’s diversity.

- Talent, market knowledge, and risk are bottlenecks. More so than in most other emerging markets, talent and market knowledge are in short supply in Africa. Political, economic, and governance risks remain in many markets. Companies must build 2020 Africa capabilities now.

- The African customer is rising. An African consumer class—and a set of thriving African companies—is emerging and starting to reach critical mass. Companies must develop products, services, and brands that resonate with these consumers and business customers. They also need to manage distribution to ensure that goods and services are delivered as promised. In other words, they need to meet the new African customer.

- Africa has an ambitious development agenda. African leaders are diligently working to improve the economic and social infrastructure of their nations. Consequently, companies should determine how they can help countries achieve their development goals while also making a profit. They need to commit to Africa.

The remainder of this report explores how to think about and do business in the new Africa by building a comprehensive plan that takes into account each of these five African realities. (See Exhibit 3.)

Bring Africa into the Boardroom

After Africa, there are no other sizable emerging markets left to enter. “The reason I came to Africa is because Africa is rising,” U.S. President Barack Obama said during his trip this June. “And it is in the United States’ interests—not simply in Africa’s interests—that the United States does not miss the opportunity to deepen and broaden the partnerships and potential here.”

It is not too late to play catch-up in Africa, but companies will need to change their mindset. When Africa was a distant trading post, it was rarely a top priority for most companies. To realize Africa’s potential, companies need to ensure that their senior executives, board members, and headquarters staff are committed to the continent. This will require that they do the following:

- Create an explicit, sizable ambition for their Africa business.

- Ensure senior sponsorship so that the Africa vision is realized.

Create an Africa Ambition

Success in Africa will not just happen. Without explicit, ambitious goals that define their aspirations for Africa, companies will struggle there. Senior leaders will not pay attention; investments will not flow; top talent will not join; and local governments will not support them.

Many multinationals have already established stretch goals for their Africa business and are working hard to achieve them. Hyundai, for example, the number-five global automaker, got serious about Africa several years ago and now has the second-largest market share on the continent, after Toyota. In the five key countries that account for 70 percent of new-auto sales—Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Morocco, and South Africa—Hyundai has surpassed Toyota. “We consider the region as a significant market and will be making strategic investments to make Hyundai cars the leading models in the region,” Sam Lee, a regional marketing director of Hyundai, told the media in 2011 when the company entered East Africa. Likewise, Samsung defined a long-term Africa strategy that has allowed the company to achieve a 20 percent share in the smartphone market.

Ambition alone is not enough, but without it, nothing else matters. If you think small, you will stay small—especially in Africa. But given the risks still remaining, companies also need to be smart about their priorities, timing, and execution.

Ensure Senior Sponsorship

In our research for this report, we did not find one global multinational that is succeeding on the continent without active, sustained, and public support from senior leaders for their Africa teams. Without such support, companies’ Africa business will fly below the radar and not receive the corporate attention that a complex set of emerging markets demands.

At General Electric, Africa is top of mind. In the company’s 2013 annual report, CEO Jeff Immelt said, “We could sell more gas turbines in Africa than in the U.S. in the next few years.” Similarly, Barclays Bank has created an African region in order to facilitate faster decision making, easier adaptation of business models, and more funding from the center. In addition, Maria Ramos, the chief executive of Barclays Africa Group, reports directly to Barclays’ chief executive, Antony Jenkins.

Africa needs to be on the CEO’s agenda, calendar, and itinerary. It is hard to imagine the CEO of a major company not visiting Asia several times during his or her tenure. But until recently, that was the norm in Africa. We surveyed 27 companies with an active presence on the continent and found that, until 2008, their CEOs had collectively made five or fewer trips annually. But in 2012, their visits more than tripled to 16, and they are on pace to make 24 visits in 2013—or nearly one per year. (See Exhibit 4.)

Address Africa’s Diversity

The continent of Africa is so vast that India, China, and the U.S. could fit within its borders, with room left over for several European nations. It comprises 54 nations with populations ranging from less than 1 million to more than 160 million, and hundreds of ethnic groups speaking more than 2,100 languages. Wealth differences are stark. Nearly three out of four people in Tunisia earn more than $2,500 annually at PPP, a level reached by less than 1 percent of the population of Liberia. Compared with other emerging markets, Africa is still relatively undeveloped. Roads, ports, and other infrastructure are often not up to grade. Suppliers of basic products and services may not exist or be able to deliver the desired quantity or quality.

The size, diversity, complexity, and volatility of Africa raise challenging organizational and business-model questions for companies. They cannot simply import a structure and a way of doing business that work in other markets. They will need to both create and empower local organizations that are close to the market and create a regional structure that takes advantage of scale and provides consistency. In particular, companies need to do the following:

- Prioritize their African markets, focusing on those that offer the best combination of attractiveness and competitive advantage.

- Organize for many Africas by leveraging either hubs or regional clusters of countries.

- Adjust their business model when the realities of Africa require different approaches.

Prioritize Your African Markets

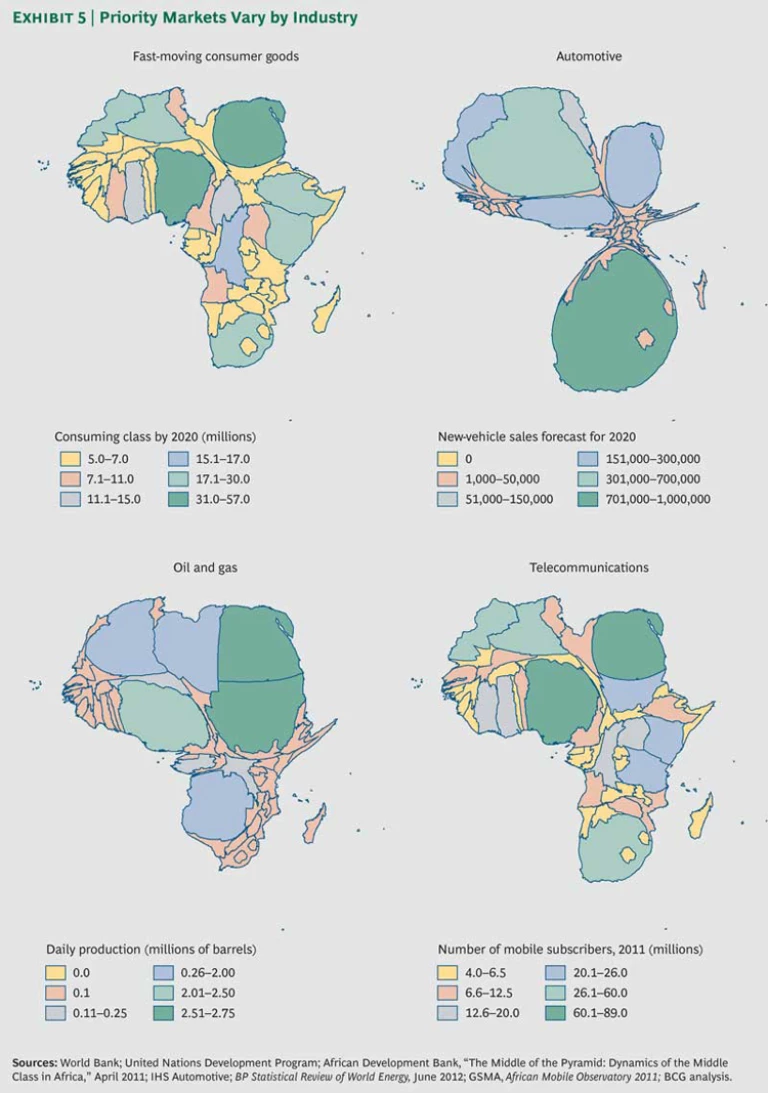

Africa’s diversity raises the stakes for companies that want to win on the continent. Even across the 11 nations responsible for 80 percent of Africa’s GDP, large variations exist in per capita GDP, the concentration and income of consumers, and other economic measures. Depending on their industry, overall strategy, risk appetite, and proximity to other operations, companies will likely make different choices about where to place bets and build businesses. (See Exhibit 5.)

For instance, while Nigeria often makes it onto lists of priority African markets because of its large population and wealth of natural resources, an active used-vehicle market makes the number of new-car sales there relatively small. In Algeria, on the other hand, there are more auto sales than the country’s population or per capita GDP would suggest, in part because of government incentives encouraging private consumption. Consequently, automakers have prioritized Algeria over Nigeria.

Another example is Nokia’s initial focus on South Africa, where the company operated through a distributor. After building its direct market presence there, Nokia expanded to Kenya and Nigeria, which it now leverages as hubs to enter adjacent markets. And a pharmaceutical company, after analyzing current and projected sales, ended up developing a three-tier prioritization of markets tailored to its growth strategy.

Organize for Many Africas

Until recently, many companies ran their Africa business from abroad. Today, many category-leading multinationals, including Coca-Cola, General Electric, and Samsung, are creating regional headquarters on the continent in order to be close to customers, stakeholders, and local talent. In 2012, for example, GE moved its regional business from Dubai to Nairobi. “We’ve got to run Africa as Africa, not as the Middle East Africa. We might as well run the Africa business out of the U.S., if we’re going to run it out of the Middle East,” said Christopher Akiwumi, corporate legal counsel of GE Africa.

Many companies divide Africa into two or more regions in order to deal with its size and take advantage of linguistic, cultural, economic, and historical linkages. The Maghreb, East Africa, Lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa are all common configurations. West Africa is often split into French-speaking and English-speaking markets. Casablanca, Nairobi, Cairo, Johannesburg, Accra, and Lagos are natural candidates as bases for such regional hubs. The Moroccan government, for example, is supporting the development of Casablanca into a regional financial hub for the Maghreb and French-speaking West Africa.

Other companies create regional shared-service operations to ensure consistent service levels and increase efficiency. Ecobank, for example, operates in 30 African nations but has created three IT hubs and three call centers to reinforce a common brand, policies, and procedures.

Companies cannot manage all their Africa businesses centrally, however, or they will sacrifice speed and agility. They need to energize and empower the local organizations in order to take advantage of market opportunity. In June, Bharti Airtel decentralized its Africa operations by making each country head responsible for investments, market-related decisions, and financial targets. Previously, all such major decisions had been made centrally in Nairobi.

Adjust Your Business Model

Africa often demands a larger presence on the ground than more developed markets. Many companies, for example, have discovered that they are unable to source various parts and ingredients from local suppliers and therefore must make their own.

MTN, a mobile operator based in South Africa, has built 6,000 microgeneration plants in Nigeria to power its cell towers because local power grids are not reliable. This has enabled MTN to gain a competitive advantage over its rivals in Nigeria. Likewise, Vale, a Brazilian mining company, has taken over construction and management of a rail line in Mozambique that it depends on to transport coal. Vale entered the rail business only after its exports suffered a two-year delay stemming from the failure of another company to complete and run the line.

Maersk has ships that can sail into Africa’s shallow waters and use onboard cranes to unload cargo in ports that lack this equipment. “In order to serve fast-growing markets, we have had to make sure that our shipping fleet has the capabilities and capacities that are required to go to ports that may not be up to the Rotterdam standard or that have inland logistics that are more complicated than those in Europe,” Nils Andersen, Maersk’s chief executive, said in an interview with BCG in 2012. To minimize the risks of doing business in Africa, Coca-Cola bottlers have built 29 small bottling plants in Nigeria and South Africa rather than the few large plants they would normally have built. This exposes the company to less disruption if a plant is taken out of service.

Finally, several companies are using mobile technologies to replace traditional services. GlaxoSmithKline has partnered with Vodafone, the GAVI Alliance (a public-private health partnership), Mezzanine (a provider of mobile medical solutions), and the Mozambique Department of Health to send text message reminders to mothers about childhood vaccinations. And Commercial Bank of Africa has partnered with mobile operator Safaricom, in Kenya, to deliver mobile banking services through its M-Shwari service rather than through physical branches. The partnership gives the bank, with just 21 physical branches in Kenya, access to Safaricom’s 19 million subscribers.

Build 2020 Africa Capabilities Now

Companies need to build stronger capabilities in order to win in any emerging market. In Africa, because governments and companies alike underinvested in education and training during the 1980s and 1990s, specific shortages and gaps require special attention.

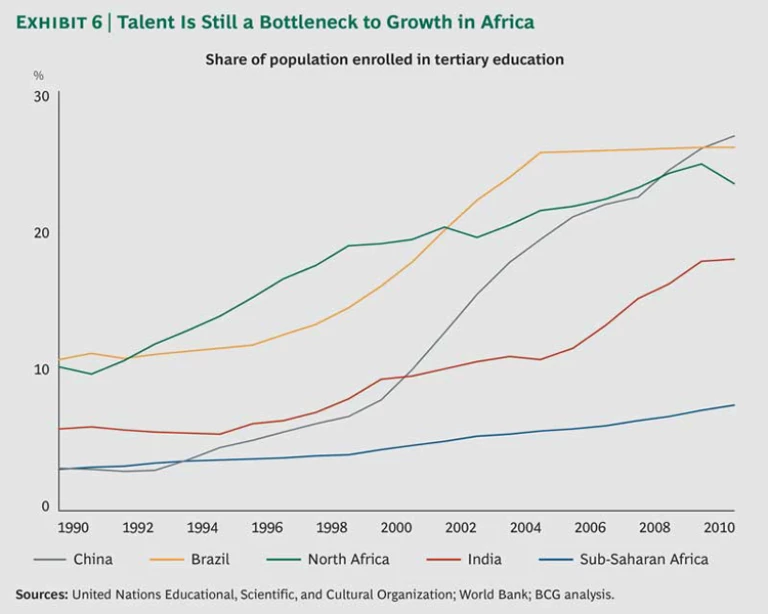

The first gap involves talent and skills acquired both in school and on the job. In 2000, only one-quarter of secondary-school-age children in Africa were attending school, less than 5 percent of young adults in the post-secondary-school age bracket were enrolled in an educational institution, and just 57 percent of adults could read. Since 2000, Africa has made great strides in education. But decades of underinvestment have created large deficits in the continent’s talent pool. (See Exhibit 6.) The University of Cape Town, the top-ranked higher-education institution in Africa, is still outside the top 100 in global rankings, and other schools are ranked even lower.

Companies, too, often did not invest significantly in the training and development of their people during the lost decades. Their leadership-development programs did not rotate rising stars throughout Africa. They did not look inside Africa for the next generation of leaders. And they did not invest in training and development programs for their African staff. Especially at the middle-management levels, the result is that companies are now left with employees who have not studied or worked abroad and frequently do not have the skills to compete in an increasingly crowded market.

The second gap involves traditional market intelligence. Until recently, few market-research firms operated in Africa. Even today, government statistics are often unreliable. The World Bank’s chief economist for Africa says that only 11 African nations have year-over-year comparable data.

The third gap is in risk management. For all the progress made in the past 10 to 15 years, Africa is still the riskiest continent in which to do business. This risk extends beyond the geopolitical sphere to the nuts and bolts of doing business. Infrastructure and services that companies take for granted in other markets—steady electrical service, smooth port operations, reliable delivery options—are missing in many places in Africa. To address these issues, companies must do the following:

- Invest aggressively in local African talent and human resources.

- Invest aggressively in market intelligence.

- Embed risk management in the organization.

Invest Aggressively in Talent and Human Resources

Some companies are starting to crack the talent and leadership code in Africa, giving them a running lead over their competitors on the continent. For example, spirits maker Diageo has reduced its share of expatriate managers in Africa from 70 percent to 30 percent through rigorous local training.

Many companies have started to tap into the African diaspora, whose members are increasingly ready to return home, as a source of talent. The Unilever Future Leaders Program, for example, encourages African business-school graduates living abroad to return to Africa. According to Jacana Partners, an African private-equity firm, 70 percent of African MBA students studying abroad would be willing to relocate to Africa. Two-thirds of all recruiting searches for African positions focus on Africans employed in the U.S. and Europe.

In addition to recruiting abroad, companies will need to nurture Africa’s home-grown talent by investing in local training and development programs. In a global rotational program established by Nokia, the top 20 African leaders receive four to five weeks of leadership training in the U.S., India, or China over the course of one year.

Invest Aggressively in Market Intelligence

Despite recent progress, reliable data about market trends, purchasing patterns, and demographic changes are hard to come by in many African markets. Further, where such information is available, it is frequently unreliable. Public statistics are often inaccurate; the informal sector and parallel imports are difficult to measure; and leading market-information providers are not yet fully established on the continent. “At the moment, Nigeria’s GDP estimate, like many statistics in Africa, is wildly inaccurate,” The Economist wrote in January 2013.

Companies frequently rely on networks of law firms, NGOs, suppliers, and trade associations to fill the gaps in “official” data. This can provide a competitive advantage. Nokia creates its own market-share statistics within several African countries by sending field teams to retail stores to gather information on product availability, selling rates, and other relevant data. The company allocates resources based on the data collected.

Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), a Brazilian public-health-research institute, worked closely with the Mozambique government to gather data on the spread of infectious and chronic diseases. That information gave Fiocruz an insider’s view into the nation’s public-health challenges. In early 2013, Fiocruz opened a plant to manufacture antiretrovirals, used in the treatment of HIV, for Sub-Saharan Africa.

Embed Risk Management in the Organization

Africa is less risky than it once was. But as more companies enter the continent, as governments assert their influence, and as social media amplify negative publicity, risk is not any easier to manage. Shell, Chevron, and other energy companies, for example, are increasingly moving oil and gas production facilities offshore in Nigeria, partly to reduce the risks of sabotage, theft, and kidnapping.

Companies have responded to Africa’s risk profile in several ways. Nestlé has centralized compliance, financial, and HR functions in a shared-service hub in Accra, Ghana, in order to reduce the risks involved in running critical functions in multiple locations in Sub-Saharan Africa. Vodacom has established dedicated teams focused on regulatory, compliance, and government relations in each country. This helps the company stay on top of local market knowledge and comply with rules and regulations in widely varied jurisdictions.

Standard Bank has both centralized and decentralized risk management. The centralized function handles broad, cross-border topics, such as money laundering and sanctions, while business units house decentralized risk functions focused on more specific and local topics. Staff members also receive extensive and ongoing training in risk and awareness.

Risk management is not just about mitigating risk but about addressing it quickly and, if the reward is sufficient, embracing it. Many multinationals have stumbled in Africa because they have taken too long to evaluate risks, losing business to more agile competitors. Those that have embedded risk management into their daily business, however, continue to thrive.

Meet the New African Consumer

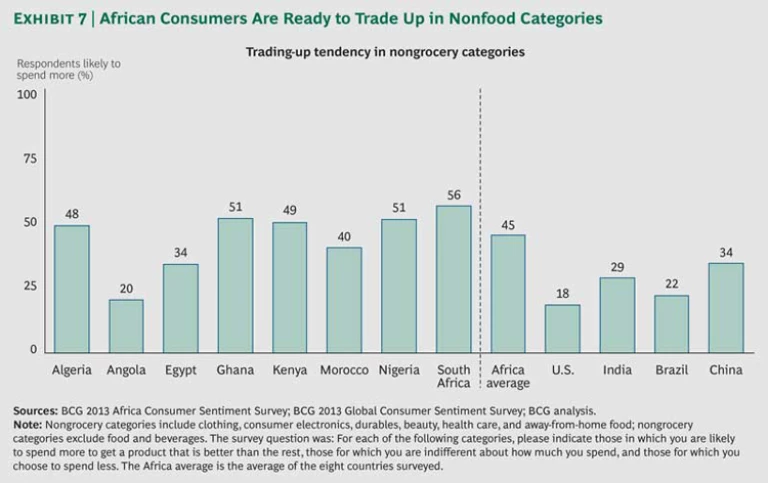

Africa’s growing economies and urbanization are increasing the number of Africans with discretionary income. Many Africans we spoke with during our research expressed near-term plans to buy laptops, upgrade their mobile phones, and spend more on entertainment, homes, cars, and education. In fact, compared with consumers in other markets, even mature ones, Africans are more likely to trade up on nonfood items, according to BCG’s 2013 Africa Consumer Sentiment Survey. (See Exhibit 7.)

African consumers, like consumers everywhere, want to buy products and services that meet their specific needs. They desire brands that connote both quality and value. And they want access to products that are available in the rest of the world. For forward-looking companies, the African market will be worth well over $1 trillion by 2020 and offer access to millions of new customers.

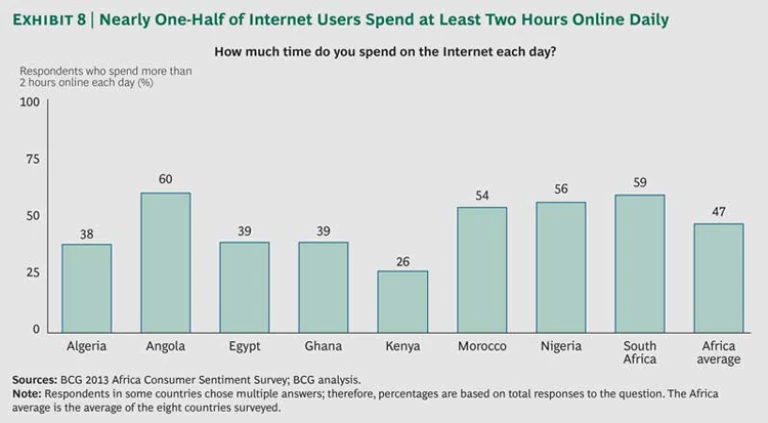

For their income levels, African consumers are heavy users of the Internet and mobile technologies, although this varies by country. In BCG’s survey, nearly half of African Internet users said they spend two hours or more each day surfing the web. (See Exhibit 8.)

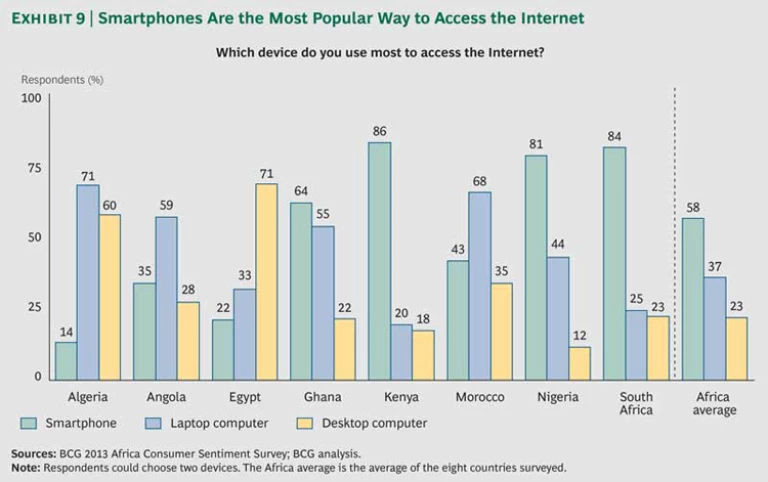

The way consumers access the Internet varies tremendously. In Sub-Saharan Africa, they primarily use their smartphones, while consumers in Algeria, Egypt, and Morocco rely more on desktop or laptop computers. (See Exhibit 9.) Mobile technology, in particular, is enabling the continent to overcome its lack of infrastructure and has enhanced consumers’ access to information and knowledge.

Digital technologies cannot cure all of Africa’s problems. While urbanization is increasing, most Africans still live in rural areas and in small villages and towns. Distribution to this “last mile” is difficult, given that only 19 percent of the roads are paved and 70 percent of the continent’s rural population lacks access to all-season roads. Vehicles tend to be in poor condition, and the destinations that companies must reach are far-flung. Few logistics companies have the comprehensive network required to ensure product delivery across multiple markets. Companies need reliable ways to reach these consumers.

The prevalence of traditional-trade formats in Africa compounds the challenges. Most people buy from traditional stores, street hawkers, kiosks, and markets. This makes distribution especially challenging for many multinationals, which are accustomed to working with modern retailers.

Finally, the African business-to-business market is a frequently overlooked segment. As African businesses expand and mature, their need for goods and services will rise. Companies in fields as diverse as advertising, equipment manufacturing, transportation, and logistics have an opportunity to jump in on the ground floor.

In order to win in this environment, companies will need to become truly local. This will require that they do the following:

- Create an African offering.

- Build and leverage brands.

- Control distribution.

Create an African Offering

Companies that have succeeded in other emerging markets have done so by tailoring their products. In Africa, however, companies cannot modify their product portfolio to appeal to all their target countries and to specific market segments within those countries. They must balance local preferences against the need to achieve scale and consistency.

Several companies have achieved success in this area. Bajaj Auto’s Boxer motorcycle became the market leader in Nigeria in two years, even though it was priced 30 percent higher than Chinese models. The product is adapted to local uses and weather conditions and is less expensive than similar Japanese vehicles.

Samsung’s appliances for the African market frequently have built-in surge protection. Its refrigerators frequently have extra insulation, and its washing machines are energy efficient. “We have a vision of developing technology that is built in Africa, for Africa, by Africa,” said George Ferreira, the chief operating officer of Samsung Electronics. “We will over the next few years be allocating more local R&D investment for further local product planning, design, and development.”

Build and Leverage Brands

The relatively short list of pan-African brands has enabled several multinationals to move into Africa and build up their own. OMO, Gillette, Colgate, Pepsi, and Nike are all well-known and well-liked brands on the continent. In Morocco, detergent is commonly referred to as Tide, while in Ethiopia, training shoes are called Adidas. In fact, according to BCG’s Africa Consumer Sentiment Survey, brands seem more important to consumers in Africa than to those in developed nations or in other emerging markets, such as China and India. (See Exhibit 10.)

The challenge is to figure out how to strengthen brands in ways that are economical and measurable. The continent’s diversity will require companies to deploy several channels and platforms. Ideally, they can leverage their global brand to fight through some of the local media clutter. Finally, companies will need to work with local governments to combat counterfeiting, which can quickly dilute the brand equity that companies spend years building.

Pepsi used the 2010 World Cup football championship in Africa to promote its products. The company created a viral music-video campaign featuring a number of famous football players, Senegalese-American singer Akon, American singer-songwriter Keri Hilson, and the Soweto Gospel Choir. Proceeds from the song were donated to charity. The campaign garnered so much media attention that many Africans believed that Pepsi was the official sponsor of the World Cup, when in fact it was sponsored by Coca-Cola.

Control Distribution

Many companies have historically relied on local distributors to deliver their goods to consumers who do not live in a port city or in one of a few other locations that they serve directly. These companies have not wanted to go to the trouble of understanding the local conditions and practices that would enable them to extend their footprint deep into the continent. It is an approach that exemplifies the trading-post mentality.

By delegating distribution, companies have often ceded control of pricing, branding, channel management, inventory—and, ultimately, profitability and competitive advantage. In our work in Africa with manufacturers of consumer goods, construction materials, and even fertilizer, distribution consistently emerges as a critical part of the puzzle. Companies cannot be successful in Africa unless they control distribution. They do not necessarily need to do it themselves. But they need to do it right, and doing it right will often require novel approaches.

About one-third of Nestlé’s sales in Africa occur through informal channels, and in order to facilitate these sales, the company has turned to a small army of distributors who travel by foot, bicycle, and car. In 2011, Nestlé was able to double its number of sales outlets in South Africa by relying on these unconventional distributors. Similarly, Vodacom has created more than 100,000 points of sale in Africa through wholesalers and independent contractors. Its Gimme That! program recruits and trains young people to sell prepaid vouchers on commission. Top performers are awarded distributor franchises. Diageo, meanwhile, trains its distributors in basic financial and sales-demand analysis and health and safety issues. The training program, called Platform for Growth, has helped increase revenues for both Diageo and its distributors.

Commit to Africa

When companies treated Africa as a trading post, their commitment and exposure to the continent were limited. They could skim off business from the coastal cities and countries without venturing into the interior. They did not manufacture locally to satisfy local demand, let alone for export. Given this limited ground presence, they saw no need to develop close ties with local officials and other stakeholders. They obtained the required permits and left it at that.

In today’s ecosystem era, companies are starting to manufacture in Africa, taking advantage of government incentives and lower labor costs. They are also actively engaging with governments and communities on numerous levels and in numerous ways. Many of Africa’s new democracies have strong economic-development policies that encourage investment, skills transfer, and social engagement. Governments are also imposing trade restrictions that make it more costly to import products that can be manufactured locally. The days of taking out raw materials and shipping in finished products are over. In this sort of environment, companies need to do the following:

- Pursue “Made in Africa.”

- Engage with their local stakeholders.

- Align with Africa’s development agenda.

Pursue “Made in Africa”

Manufacturing in Africa is rapidly increasing, both for export and to meet local demand. The cost of labor is lower in Africa than in the BRIC nations, and many raw materials, such as leather and cotton, are cheaper. African governments are also offering incentives to encourage capital investment and local manufacturing by foreign investors.

For all these reasons, it makes sense for companies to consider establishing manufacturing facilities in Africa. Some companies have started to follow this path, including Samsung, which has established five manufacturing facilities in Africa in the last five years. Its Ethiopian plant was built, in part, to avoid a 60 percent duty on goods imported into the country, while its Kenyan plant takes advantage of the country’s relative strengths in talent, technology, and skilled labor.

Renault has invested more than $1 billion in a plant in Morocco that will produce 400,000 vehicles annually, both for domestic consumption and for export. Morocco has developed an aggressive plan to boost local manufacturing—in industries such as automotive, aerospace, electronics, and renewable energy—that is similar to China’s Special Economic Zones and Mexico’s maquiladoras. The country hopes to take advantage of its favorable labor costs, proximity to Europe, improving infrastructure, and free-trade agreements.

Similarly, Ethiopia is encouraging the development of textile and other labor-intensive manufacturing. Its government has set an ambitious target of $1 billion in textile exports by 2016 and is bringing in foreign investors to modernize machines and factories. H&M Hennes & Mauritz, the Swedish apparel maker, has placed test orders in Ethiopia in order to expand its supplier base.

Some companies have discovered that they can improve the freshness and availability of their products, and their bottom lines, by sourcing locally. Danone has been sourcing milk products locally since it bought a South African dairy processor in 2009. Likewise, SABMiller sources barley from 45,000 African farmers.

Finally, many companies have been able to take advantage of the U.S. African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). The act allows Sub-Saharan nations to export certain goods into the U.S. duty-free if they can show progress in opening their economies, protecting human rights, and reducing corruption. AGOA exports to the U.S. climbed to $34.9 billion in 2012, more than four times the amount in 2001, when the law took effect.

Engage with Your Local Stakeholders

As companies increase their presence in Africa, they need to become skilled at working with governments, NGOs, and other stakeholders that hold power or influence public opinion. Many pharmaceutical companies, for example, try to supply local governments with low-cost medicines in order to build relationships, brand awareness, and connections with consumers. In many African nations, they also work with NGOs such as the Gates Foundation, which awarded more than $3 billion in grants on the continent in 2012 alone.

Mining companies in Africa and elsewhere have discovered that their ability to operate in local communities depends on their engagement with those communities. During their active lifetimes, mines become social and economic engines. By investing in social and environmental initiatives, a company can ensure greater stability for its operations, because the people living and working around its facilities benefit from and therefore support its activities.

Companies are finding that when they successfully manage their social and environmental footprint in this way, they can maintain a “license to operate.” This is not a formal agreement but rather the implicit consent of government and society to allow a company to carry out its commercial activities with a minimum of regulatory interference or opposition from the local community.

Sometimes, competitors in Africa realize that it makes more sense to cooperate than to compete. Mobile operators MTN and Airtel, for example, are sharing the costs of telecommunications infrastructure, such as cellular towers and fiber cables. The agreement is likely to save the two companies $8 billion in capital costs.

Align with Africa’s Development Agenda

For companies to succeed in Africa, they need to pursue business opportunities that are aligned with a country’s or a region’s development agenda in support of local manufacturing, job growth, and skills transfer. Companies should partner with government by identifying key public stakeholders and pursuing projects and businesses that will advance the agenda. They should rigorously track performance against targets and goals.

By helping governments achieve their development goals, companies will have an easier time both doing business and achieving their own objectives. In Morocco, for example, companies that produce or source locally are given preferential treatment in the awarding of government contracts. Other companies, such as Anglo American, make a commitment to hire a certain percentage of local employees, purchase a set share of their supplies locally, and assist in the creation of local businesses. In Nairobi, IBM’s technology center is working on potential innovations that will ease the strain on public water and transportation systems created by a rapidly growing population and otherwise contribute to sustainable economic development.

Building an African Ecosystem

This report has explored Africa’s arrival on the global economic map, laid out the challenges, and proposed actions for winning in Africa. BCG also has several field-tested methodologies and approaches, such as the global readiness index, the emerging-markets acceleration program, and the Africa readiness index, that can help in assessing companies’ starting position and putting them on the road to success in Africa.

Most important, companies must evaluate their performance and priorities on the continent, and executives should be asking themselves and their organizations whether they are ready to win in Africa by moving quickly and building an ecosystem, rather than relying on the trading posts of the past. (See “Are You Building an African Ecosystem?”)

ARE YOU BUILDING AN AFRICAN ECOSYSTEM?

Below are some questions to help you assess whether your African operations are geared for success.

Bring Africa into the Boardroom

- Create an Africa ambition. Do you have specific revenue, investment, and market-share targets for Africa and key markets within it?

- Ensure senior sponsorship. Has your chief executive visited Africa within the past year? Do you have an “Africa champion” on your leadership team?

Address Africa’s Diversity

- Prioritize your African markets. Are your market prioritization and sequencing aligned with your strategy?

- Organize for many Africas. Does your Africa organization have the right balance between localization and scale, make use of hubs or other mechanisms to make the continent manageable, and empower local leaders to win?

- Adjust your business model. Have you identified adaptations to your business model in order to compete more effectively in your priority Africa markets, and have you made those changes?

Build 2020 Africa Capabilities Now

- Invest aggressively in talent and human resources. Have you put in place recruiting, training, and development programs to cultivate strong local leaders and effective middle managers?

- Invest aggressively in market intelligence. Do you have plans for overcoming Africa’s gaps in market research, macroeconomic data, and other intelligence? Have you considered how you can create competitive advantage by developing this intelligence?

- Embed risk management in the organization. Do you understand the key risks of African markets, and have you developed a plan to address them with traditional risk-management activities and creative approaches that minimize exposure?

Meet the New African Customer

- Create an African offering. Have you identified the changes you must make to your products and services to ensure their appeal in your key African markets?

- Build and leverage your brands. Do you know how your brands are perceived in your key African markets and do you have a plan to establish, build, and protect them?

- Control distribution. Have you identified the optimal distribution models in key African markets and moved to direct and control them?

Commit to Africa

- Pursue “Made in Africa.” Have you identified opportunities to locally manufacture, assemble, or otherwise add value to your African products? Have you considered Africa’s advantages as a sourcing location for your international markets?

- Engage with your local stakeholders. Have you identified and prioritized the top strategic stakeholders in your key markets at the national, provincial, and local levels?

- Align with Africa’s development agenda. Are you aware of the government’s economic-development objectives in key African markets, and is your organization shaping its local business-development strategies to align with them?

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Adam Alagiah, Charles Boatin, Pia Carona, Garett Chau, Graham Fizer, Belinda Gallaugher, Alexandre Gorito, Ayoub Mamdouh, David Michael, Brian Sangudi, Lori Spivey, Andrew Tratz, Mark Voorhees, Carey Wikstrom, and Nomava Zanazo for their assistance in the research, writing, and marketing of this report.