IT outsourcing has the potential to add considerable business value—in the form of greater IT cost-effectiveness, improved quality of delivered IT services, and greater IT-driven agility—for companies that deploy it successfully. Yet the real-world track record of IT outsourcing is, on balance, underwhelming. In fact, in a recent study on outsourcing by BCG, only a bit more than half of the large IT outsourcing deals in the sample were deemed at least moderately successful by the companies that initiated them.

Reasons for IT outsourcing’s frequent failure to deliver full value vary. They include such factors as inadequate transparency of contract pricing and a lack of agreement on incentives and objectives between a company and its vendors. But a particularly critical factor is a lack of necessary capabilities in the retained IT organization. Simply put, the streamlined IT organizations that many companies retain as they embrace outsourcing often lack the skills, knowledge, leadership, and management capabilities vital to making those very outsourcing efforts work. (See “Increasing the Odds of Success in IT Outsourcing,” BCG article, December 2013.)

Righting the ship entails taking a close look at the retained IT organization’s skills and capabilities, and identifying and filling holes where they exist. It also demands effective orchestration—that is, managing in a tightly coordinated fashion the different internal IT functions, external providers, and interactions with the business.

A Broad Mandate

Today, virtually every large company outsources elements of IT service delivery to a degree, with some companies seeking to outsource as much as possible. But there is always a part of the IT function that remains in-house: the retained IT organization.

Retained IT organizations have a broad mandate and must routinely wrestle with decisions about their scope and setup. Questions they must answer include the following:

- How can we ensure that we have a strong understanding of the business and that we use that understanding to deliver IT products and services that improve the business’s performance?

- How can we ensure that IT services delivered to the business—whether by vendors or by internal staff—are of sufficient quality? How can we make sure that they are delivered at sufficiently low cost?

- How can we work with the business to control demand for IT services? What role should vendors play in managing demand?

- How can we maintain the right set of in-house skills and competencies, even as our talent base shrinks as a result of outsourcing?

- What governance model will allow us to manage external service providers effectively without having to shadow or micromanage them?

- Retained IT organizations have a lot on their plate. And many, our experience shows, are not up to the task.

Orchestrating Value

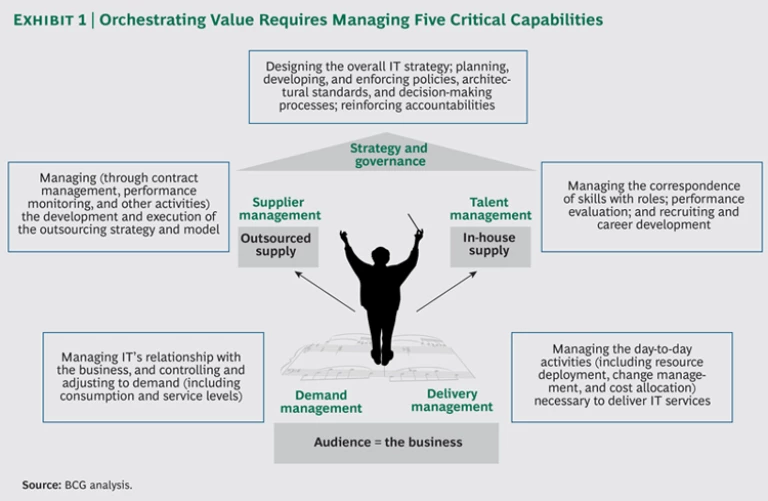

To ensure that they can execute their vital role with regard to IT outsourcing, retained IT organizations must essentially do two things. One, they must manage their various responsibilities, capabilities, and personnel in a highly coordinated fashion. The analogy to an orchestra conductor is apt. The retained IT organization must ensure a coordinated performance from the entire “orchestra”—meaning both vendors and internal delivery groups. It must design a “repertoire” (that is, a portfolio of IT services) that meets the desires of the audience (that is, the business). And it must execute that repertoire at a caliber that satisfies the audience.

Two, retained IT organizations must confirm that they have the necessary capabilities in five principal areas: strategy and governance, supplier management, talent management, demand management, and delivery management. (See Exhibit 1.)

Strategy and Governance. Retained IT organizations must define a mix of services, provided by external or internal suppliers, that support the company’s strategy and objectives and are consistent with IT’s overall strategy and capabilities. The mix will obviously vary by company: an IT organization focused on operational effectiveness will have different goals when defining its required services and sourcing strategy than an IT organization focused on agility and innovation, for example. Retained IT organizations must also have strong enterprise- and solution-architecture capabilities. And they should have a governance model that spans all relevant parties and ensures effective management of external providers at the delivery, commercial, and relationship levels.

Supplier Management. Retained IT organizations must be adept at managing outsourcing contracts. This is no easy feat. A common problem is that contracts are typically negotiated by a dedicated deal team but managed on a day-to-day basis

by a separate group of individuals, few if any of whom were involved in the negotiation. It is critical, therefore, to form a strong linkage among the deal team, the contract management team, and the delivery management team when designing and negotiating contracts. This can be facilitated by including people on the deal team who will later manage the contract or its delivery.

Retained IT organizations must also move away from traditional models of managing suppliers. In a multivendor sourcing model, for example, managing each supplier with a discrete, individualized set of service level agreements or KPIs, as is customary, will not necessarily guarantee high-quality end-to-end service delivery. In the case of a multivendor model, the better practice is to incorporate KPIs that span multiple suppliers. (See “Shared KPIs in Multivendor IT Outsourcing: Turning ‘I’ to ‘We,’” BCG article, February 2011.)

Talent Management. Maintaining critical in-house skills and competencies, especially when the company employs a highly outsourced delivery model, is essential. Often, heavily outsourced IT organizations have a limited pool of internal talent to draw upon, and working for these organizations is seen by internal prospects as career limiting. Further, such organizations often deploy talent without giving any thought to whether those individuals have the required skills for their assigned roles—slotting an engineer who has limited customer-service skills or knowledge of the business into a demand management role, for example.

Retained IT organizations must find creative ways to recruit top talent and ensure that skill sets correspond to roles. (See “Optimizing Talent Management.”) To retain such talent, IT organizations should also create sufficient flexibility within the organization to permit career development and growth.

OPTIMIZING TALENT MANAGEMENT

An Achilles’ heel for many retained IT organizations is talent management. Many treat the topic far too narrowly, focusing disproportionately on the organization’s top talent. They also pay insufficient attention to matching skills with roles and other considerations. This can come at a high cost, given that the retained IT organization’s internal needs can change significantly as it adjusts its balance between internal and external providers.

To derive maximum value from internal staff, a retained IT organization must have a comprehensive scheme for talent management. The organization should clearly define all necessary internal roles and their respective skill requirements, and distinguish between generalist and specialist roles. It should then catalog existing internal skills and determine where training and the acquisition of new skills are required in order to fill gaps.

Decisions about specific roles and whether they can be filled by internal staff should be based on pragmatism rather than on familiarity with individuals or their tenure in the organization. Some companies, for example, will try to move purely technical types, such as engineers or technologists, into roles (such as vendor management) that require substantially greater customer-facing or management skills than those individuals possess. The results usually suggest that it would have been wiser to recruit the necessary skills from the outside than to try to fit the proverbial square peg into a round hole.

Vendors are often a ripe source of specific talent, and some companies have structured formal agreements with their vendors to acquire it. Some companies, for example, have agreed to preplanned rotations of talent between the parties. One took it a step further, specifying in the contract that it would have the right to draw talent, on a full-time basis, from the vendor’s ranks. Internal staff is also obviously fertile ground for filling specific positions. The recruitment and retention of top internal talent can be facilitated through the establishment of career development guidelines and incentives. A company could, for example, encourage internal talent to spend a specified period working in the retained IT organization as a stepping-stone for moving to other attractive and advanced roles in the company.

Optimized talent management also entails identifying critical individuals and roles, and defining retention strategies and contingency plans. The list of individuals and roles should be dynamic, changing with the organization’s strategic priorities. The retained IT organization should also invest in employee development through training and by rotating people through different roles and responsibilities. Finally, it should ensure that rigorous performance management is in place, particularly to develop and handle poor performers and employees whose skills don’t match the demands of their roles.

Demand Management. The retained IT organization is expected to adjust to changes in the nature and volume of business demand for IT services. Simultaneously, it must attempt to steer demand in a manner that limits non-value-added complexity. Tackling these challenges successfully requires a deep understanding of the business. The use of external service providers only magnifies the challenge.

To manage demand effectively, the retained IT organization must do three things. It must give external providers a seat at the table in discussions with the business about demand management. It must ensure, through the creation of architectural standards and governance forums, that external providers strive to meet demand by using standardized, rather than customized, solutions. And the retained IT organization must develop explicit service-level metrics and targets, as well as financial incentives, that encourage vendors to proactively control and manage demand.

Delivery Management. Many retained IT organizations struggle to ensure that IT services are consistently of sufficient quality and are delivered on a timely basis and at reasonable cost. The challenge can intensify when the company uses multiple vendors for service delivery.

Effective management of service delivery demands several things of the retained IT organization. One, the organization must commit to managing service delivery outcomes internally rather than outsourcing the task. Two, it must seamlessly integrate delivery from external and internal service providers by clarifying roles, ensuring that the parties work together effectively, and creating transparency regarding service problems and requests. Three, the retained IT organization must foster the right internal mind-set, placing greater emphasis on the ability to detect and understand problems—and negotiate and track solutions (potentially involving multiple suppliers)—than on operational capabilities, for example.

A Success Story

The experience of a large transportation and construction company illustrates the value a retained IT organization can bring to an outsourcing program. The retained organization supported a number of different geographically dispersed businesses, each with its own IT needs. Outsourcing played a significant role in its strategy, accounting for about 40 percent of total IT spending. Service delivery was divided between two vendors; the organization used a third vendor for service integration.

The retained IT organization found itself facing a number of problems in service delivery. Benchmarking revealed that it was spending 15 to 35 percent more than comparable organizations—and IT managers did not understand why, especially since the services delivered were subpar. High frustration among business users had spawned considerable use of “shadow IT” in various business units and field offices. And the retained IT organization believed it was vulnerable to too-high levels of business-continuity and disaster-recovery risk.

Upon analysis, the retained IT organization identified some reasons for the problems. Having an external service integrator responsible for coordinating the efforts of the vendors and managing their contracts had led to service quality issues, including delays in service provisioning and problem resolution. The retained IT organization had not put in place incentives to encourage the service integrator and vendors to improve service quality. And no one within the retained IT organization was familiar with their contracts or had any vendor-management experience.

Further, internal IT staff was focusing too much on shadowing vendors and performing tactical delivery activities, and too little on managing the overall delivery of services. The situation was exacerbated by significant gaps in technical and execution capabilities in the retained IT organization.

The retained IT organization also determined that it was not structured to interact effectively with the business. There were multiple points of contact between IT and the business in some divisions and none in others. This was compounded by the absence of appropriate joint-governance forums.

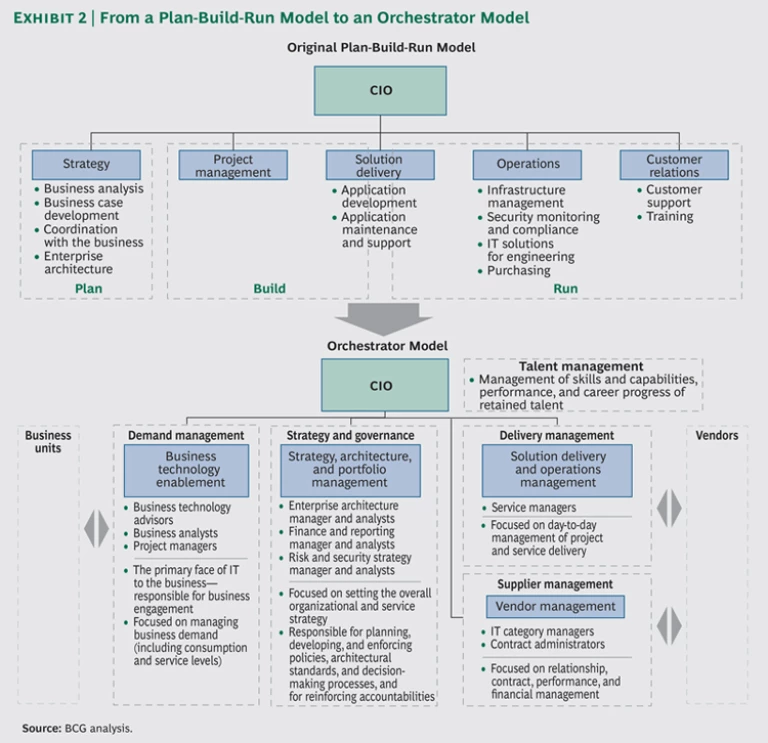

To remedy these ills, the retained IT organization redesigned its organization model and redefined a number of roles. Previously, it had organized itself according to a traditional plan-build-run model, with groupings for strategy, project management, solution delivery, operations, and customer relations. (See Exhibit 2.) Highlights of the effort included the institution of three functions: a vendor management function focused on thoroughly understanding and effectively managing vendor contracts; a business-technology-enablement function aimed at facilitating both the tailoring of solutions to the business’s needs and the use of standardization where appropriate; and a solution-delivery and operations-management function focused on establishing clear ownership of each service and managing service delivery by both outsourcers and in-house staff.

To match newly defined roles with the appropriate skills, the retained IT organization thoroughly evaluated its talent pool. It retained top talent, inculcated new skills into existing talent where necessary and possible, and hired from the outside to fill critical roles when the required skills did not exist in-house. Those efforts, combined with the new organization model and the actions described above, put things back on track and gave the institution what it needed to orchestrate the delivery of high-quality services.

A fit-for-purpose retained IT organization, one that is sufficiently skilled and an effective orchestrator of capabilities, is an essential pillar for the maximization of value from IT outsourcing efforts. Getting there can require time and investment. But the payback can be substantial.