Growth can be a way for nonprofit organizations to have greater impact, increase scale, reduce costs, improve efficiency, and attract investors. But growth comes with risks, too—especially if it is not supported by a well-defined strategy and roadmap.

Case in point: A nonprofit based in the US planned to extend its reach and impact by replicating its service model in other regions of the world. But its growth agenda encountered speed bumps along the way. Issues such as volatile sources of funding, high attrition, and a tendency to overcustomize country models hindered expansion, and the hoped-for increases in scale, efficiency, and impact failed to materialize.

The reality is that a solid foundation for sustainable growth must be in place before expansion begins—and the more aggressive the expansion plan, the stronger that foundation must be. Before moving forward, organizations must determine what type of growth strategy they’ll follow and assess their overall readiness.

Three Types of Growth

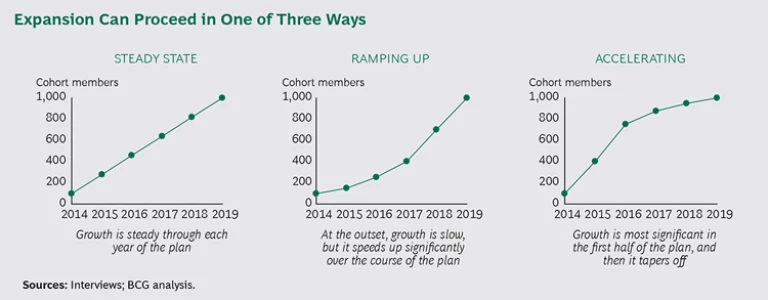

Expansion can proceed in one of three ways: by following the same steady-state rate of growth each year; by ramping up expansion over time; or by accelerating growth in the near term. (See the exhibit, “Expansion Can Proceed in One of Three Ways.”) Each approach has benefits and trade-offs.

Steady-state growth aims for the same degree of growth each year of the expansion plan. The benefits of a steady-state strategy include annual goals that are predictable, challenges that tend to decrease over time as experience increases, and the option of boosting growth targets if the initial performance is strong. On the minus side, this approach may not match the organization’s needs, political context, or fundraising challenges in a given year. What’s more, should the organization fail to meet its goals, people might feel discouraged and think, “We’re already behind. There’s no way to catch up.” A ramping-up growth strategy involves slow growth at the outset of the expansion plan, with significant increases in the following years. Ramping up growth over time also delivers benefits and trade-offs.

On the one hand, it allows an organization to identify which capabilities and systems are lacking and provides the needed time to build capacity—all of which can reduce organizational strain. This strategy requires patience, but because it increases the likelihood of achieving initial goals, it enhances momentum and morale.

On the other hand, political support or fundraising may disappear before the goals are reached, and staff members may face greater challenges each year. When the dust settles, the organization may achieve little beyond its initial goals.

With an accelerating-growth strategy, the biggest growth occurs in the first half of the expansion plan and then tapers off. In the near term, such an approach allows the organization to capitalize on a window of opportunity, and ambitious goals can increase the likelihood of achieving high growth. But this strategy can be hard on staff members, and it may be very difficult to execute unless the needed capacity and capabilities are already in place. And if the organization fails to meet the stretch goals, its reputation could be tarnished.

Which strategy to choose?

Assuming that steady-state growth is the default path, when should an organization decide to pick up the pace, either by ramping up over time or by choosing an even more rapid acceleration of growth initially? Ramping up over time is a good choice when the nonprofit has a steady and predictable source of funding, a long history of political support and partnership, and growth that requires investments over time in capacity or capabilities (such as a new location or additional staff). The ramping-up approach is also best if the organization is relatively new, is struggling to find and hire the right people, is worried about staff burnout, or needs to strengthen its processes and controls (such as communications or expense approvals) in order to reduce risk as it grows.

Accelerated growth can succeed if the organization has already invested in needed capacity and capabilities (having, for example, anticipated and filled the need for a regional director) and has plenty of strong potential recruits, a robust brand, credibility with partners, healthy morale, and the ability to provide intensive support to new sites. Another reason to consider a rapid-growth strategy is if a window opens to a political or fundraising opportunity that may not last—such as an imminent change in a political party.

Whichever strategy you choose, market dynamics and the needs of your organization’s operating model could restrict your growth trajectory—or force a reassessment. Moreover, the issues of funding, capabilities, capacity, and leadership are the same whether a nonprofit is large or small.

Assessing Your Readiness

Before executing any growth strategy, an organization must have a solid foundation to build on. On the basis of our extensive work in a wide range of industries, we’ve distilled six key questions that will help your nonprofit assess its readiness for growth:

Have you earned the right to grow? Before scaling up, make sure you have high-quality programs or services that deliver on your mission. Measurable results are increasingly important in the social sector. How many deaths were prevented? How many fewer school days were lost due to illness? How much more food is available to the hungry? How much did test scores increase? How many students graduated, compared with the unassisted population? How much was life expectancy extended? How much did infection rates decrease?

Pathways to Education, a community-based program for high school students from low-income families in Canada, aims to break the poverty cycle by reducing high-school dropout rates. By working with the school board, Pathways gained access to crucial data on course and graduation outcomes. The impact of the program proved to be high. Participating students had a 70% lower dropout rate than their at-risk peers, and the university enrollment rate is three times the pre-Pathways baseline. Just as important, the study showed that every dollar invested in Pathways delivered $24.50 in social returns for the broader community through higher incomes and taxes and by avoiding social costs in health care and the justice system. Armed with this data, which it regularly updates, Pathways developed an ambitious plan to scale up its operations by collaborating with a range of outside supporters from the private and public sectors.

Pulling together the right metrics can be complex, especially for smaller organizations that have limited resources or lack the necessary analytical skills. Furthermore, the social sector provides a wide range of services to varied populations, often in partnership with multiple organizations, and outcomes are highly variable as a result. To the best of your ability, before deciding to expand, make sure that your organization has an effective model in place and is meeting the goals it has set to measure its program quality and impact.

Do you manage your costs effectively—and understand how they’ll change with expansion? It’s also important to understand your cost structure and the added costs of growth or of operating in a new region. Be sure to assess the break-even or the minimum scale required to succeed. Benchmarking your current costs against those of other organizations at a similar stage—or against other sites in your network—can help your team identify the key budget drivers and where costs are out of line. Costs to explore include total administrative costs, fundraising costs, and costs per employee. Your organization’s size, growth phase, and regional structure will likely drive the economics.

For example, one global nonprofit discovered its operating costs per employee were highest in countries in which it had the most extensive management structure. In regions with more centralized organizations, these operating costs were lower. It isn’t unusual for organizations that are in the start-up phase and still building up staff to have lower operating expenses per employee than more established organizations.

Be aware that costs per employee can increase during expansion as a result of investing ahead of the curve, the added complexity of new regions, and not managing for efficiency. Also, some functions are more scalable than others. Functions such as IT, finance, communications, strategy, development, alumni, and HR tend to be the most scalable. Once established, they can be leveraged across a large number of sites. Training, development, recruitment, placement, and community relations, which are less scalable, typically require additional investment as the organization grows into new regions.

Are the conditions for success in place? Before moving forward with an expansion plan, confirm that there truly is a need for your products or services in the target area(s) and that any resources you will need—such as staff, partners, and government support—are available. Be sure that the leadership team is committed to the chosen strategic direction and that expansion efforts have a clear focus.

Grameen Distribution is a social business—a company created for social benefit rather than private profit. Grameen saw that Bangladesh’s rural populations needed but lacked access to essential products such as light bulbs, mosquito nets, solar lights, and clothing. Reaching the remote regions was a major logistical challenge, however. To expand into these areas, Grameen recruited and trained a large group of village women to be local distributors in their communities. With this new microfranchisee model, the company tapped into an unserved new market for its products, while also providing valuable employment opportunities for local women. But before moving forward, the company made sure that there was a need for its products and that local women could serve as distributors.

Can you fund the growth? To achieve sustainable growth, nonprofits require a consistent source of financial support—from governments, individuals, corporations, or foundations or from a combination of all four—and an effective fundraising strategy. Without a working development engine, the organization will be unable to execute its growth strategy.

Nonprofits operate under unusual circumstances. They may have committed funds that don’t arrive in predictable ways, are delivered over the course of multiple years, or arrive at the end of the year in a lump sum. In many cases, donors have demands or impose restrictions on funds, earmarking them for specific programs. These restrictions can reduce flexibility, so a 12-month risk-timing analysis must underlie any effective funding strategy. For growing organizations with constant needs, this can be a challenge, and forecasting skills become critical—separate and distinct from budgeting skills. At some organizations, a steady growth trajectory is supported by consistent funding from government or another source. For instance, they may receive funding on a per-beneficiary basis in addition to grants for new locations. This allows for accurate cost forecasting and the ability to determine the break-even point. Although this degree of predictability is desirable, it’s also rare in the nonprofit sector. It’s best to create a budget with a cushion—such as 130% of estimated costs.

Do you have the right people and leadership? In our experience, most leaders have to devote more effort to growth than to other types of change. The visionary, inspirational skills needed for the start-up phase of an organization are typically different from the skills needed for the growth phase. (See “Organizing for Growth,” BCG article, October 2014.) The smart founder recognizes when to step aside—or at least when to share management responsibilities with a leadership team that has complementary skills. The same is true for staff members. Although hiring managers tend to focus on education, experience, or expertise, it’s just as important to bring in people with a range of cognitive styles—including creative thinkers with big ideas and those with the attention to detail needed to execute a plan, followers and leaders, introverts and extroverts, those with a tolerance for ambiguity and those who need clear direction. All bring needed capabilities to the table.

Recruiting and retaining good people is always a challenge for nonprofits, which often lose potential hires and trained staffers to higher-paying jobs in the private sector. Save the Children had to rethink its approach to hiring in order to attract and retain ambitious, talented staff members to tackle emergencies. Instead of viewing disaster response personnel as members of a list or roster, the organization created a “career path in humanitarianism,” which includes a diverse range of experiences and advancement opportunities.

Is your organization model scalable? Before scaling up, make sure that your strategy and organization structure can be replicated and exported and that key processes are robust and consistent. Consider, too, that growth can tax your people. The right disciplines and incentives must be in place to keep your work force engaged and motivated. An organization model with consistent processes and proven economics is more easily transferred to other locations.

The success of Aravind Eye Care in India is a strong example of these principles. The founder set a goal of delivering free—or nearly free—eye care and surgery to India’s poor by offering treatments at a fraction of what they would cost in developed countries. In Aravind’s model, paying patients subsidize treatments for the poor. The organization keeps costs down by running a fast, efficient, and high-quality “factory” for eye care, achieving economies of scale and expertise that drive quality. Doctors sit between two operating tables, and when they finish working with one patient, they literally turn to the next, who is already prepped and ready for treatment.

Considered together, these six questions combined with a clear growth strategy can help your organization’s leadership team determine its readiness for growth and the pace at which to proceed. Given their enormous contributions to society and the urgent need for their services, nonprofits must have the ability to scale up their operations effectively so that they can exponentially increase the impact they deliver across the globe.

This content was originally published by The Chronicle of Philanthropy.