Companies operate in an increasingly complex world: Business environments are more diverse, dynamic, and interconnected than ever—and far less predictable. Yet many firms still pursue classic approaches to strategy that were designed for more-stable times, emphasizing analysis and planning focused on maximizing short-term performance rather than long-term robustness. How are they faring?

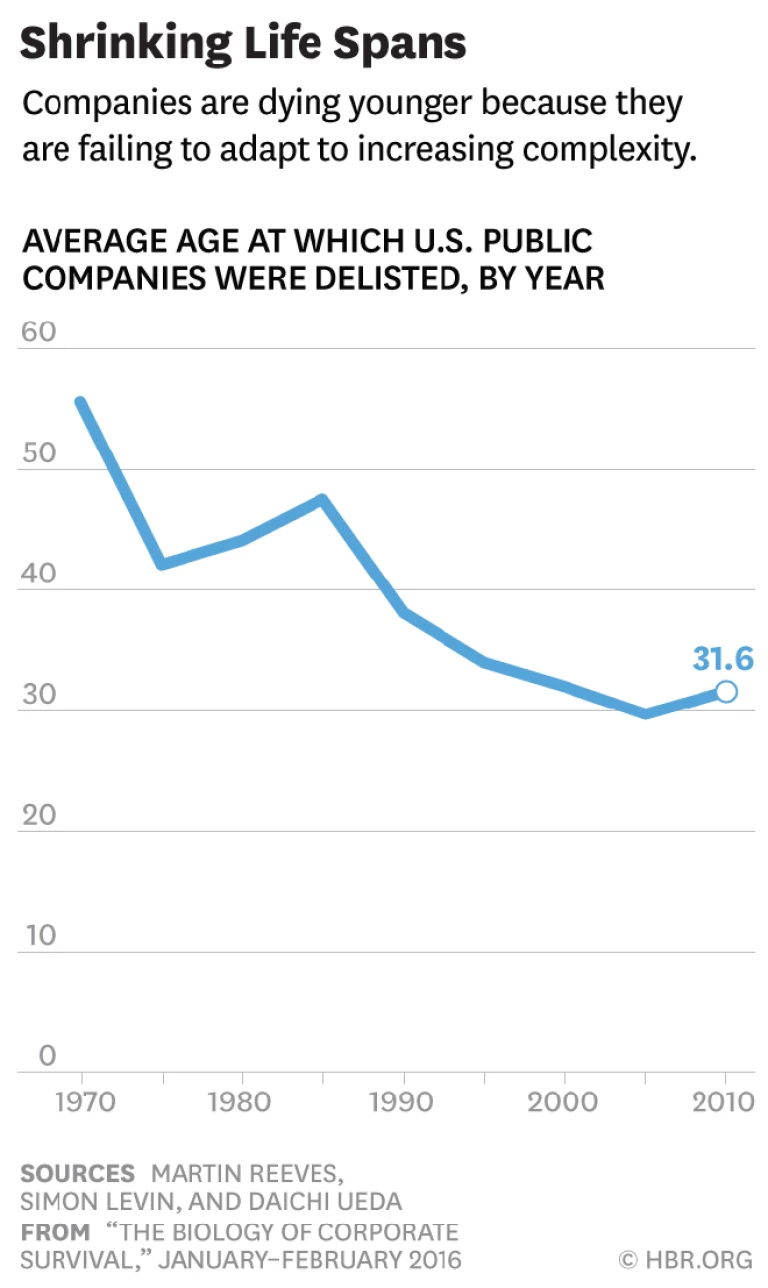

To answer that question, we investigated the longevity of more than 30,000 public firms in the United States over a 50-year span. The results are stark: Businesses are disappearing faster than ever before. Public companies have a one-in-three chance of being delisted in the next five years, whether because of bankruptcy, liquidation, M&A, or other causes. That’s six times the delisting rate of companies 40 years ago. Although we may perceive corporations as enduring institutions, they now die, on average, at a younger age than their employees. And the rise in mortality applies regardless of size, age, or sector. Neither scale nor experience guards against an early demise.

We believe that companies are dying younger because they are failing to adapt to the growing complexity of their environment. Many misread the environment, select the wrong approach to strategy, or fail to support a viable approach with the right behaviors and capabilities.

How, then, can companies flourish and persist? Our research at the intersection of business strategy, biology, and complex systems focuses on what makes such systems—from tropical forests to stock markets to companies themselves—robust. Some business thinkers have argued that companies are like biological species and have tried to extract business lessons from biology, with uneven success. We stress that companies are identical to biological species in an important respect: Both are what’s known as complex adaptive systems. Therefore, the principles that confer robustness in these systems, whether natural or manmade, are directly applicable to business. To understand how, let’s look at what these systems are and how they function.

A Complex Business

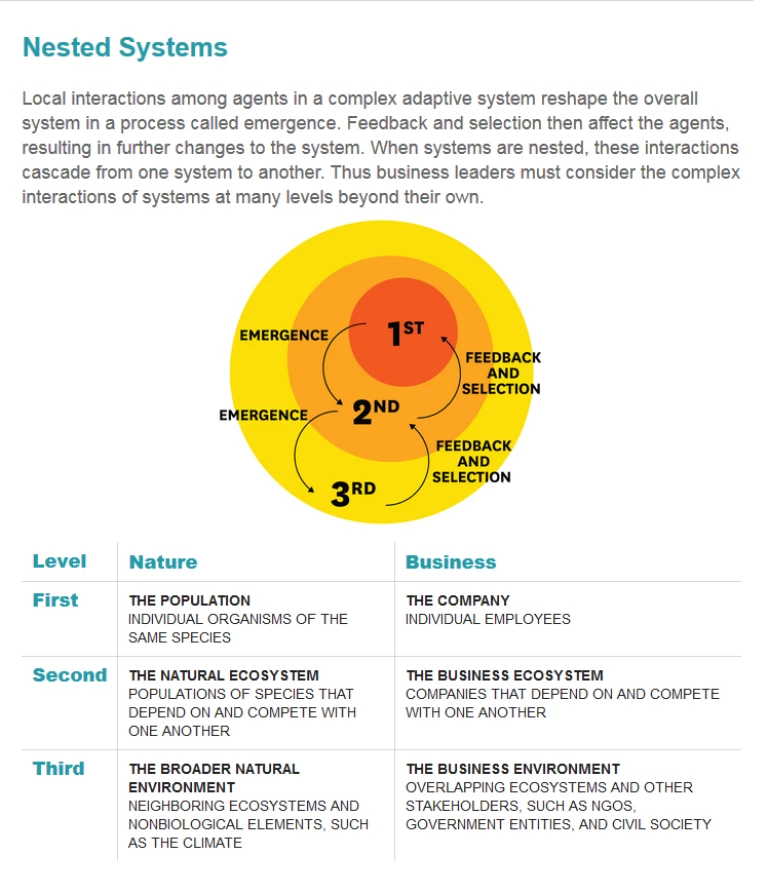

In a complex adaptive system, local events and interactions among the “agents,” whether ants, trees, or people, can cascade and reshape the entire system—a property called emergence. The system’s new structure then influences the individual agents, resulting in further changes to the overall system. Thus the system continually evolves in hard-to-predict ways through a cycle of local interactions, emergence, and feedback. In nature we see this play out when ants of some species, for example, although individually following simple behavioral rules, collectively create “supercolonies” of several hundred million ants covering more than a square kilometer of territory. In business we see workers and management, through their local actions and interactions, shape the overall structure, behavior, and performance of a firm. In both spheres these emergent outcomes influence individuals and create new contexts for their interactions. Whether we look at team dynamics, the evolution of strategies, or the behavior of markets, the pattern of local interactions, emergence, and feedback is apparent.

Complex adaptive systems are often nested in broader systems. A population is a CAS nested in a natural ecosystem, which itself is nested in the broader biological environment. A company is a CAS nested in a business ecosystem, which is nested in the broad societal environment. Complexity therefore exists at multiple levels, not just within organizational boundaries; and at each level there is tension between what is good for an individual agent and what is good for the larger system.

What does this mean for business leaders?

First, they need to be realistic about what they can predict and control, what they can shape collaboratively, and what is beyond the reach of managerial influence. In particular, they need to expect that unpredictable and even extreme emergent outcomes will cascade from actions at the lower levels. A clear example is the financial crisis of 2007–2008, during which risk created by subprime lending in the US real estate market spread catastrophically throughout the global financial system.

Second, they need to look beyond what their firms own or control, monitoring and addressing complexity outside their firms. CEOs must ensure that their companies contribute positively to the system while receiving benefits sufficient to justify participation. Companies that fail to create value for key stakeholders in the broader system will eventually be marginalized (similarly, business ecosystems that do not provide benefits to their members will experience defections). Consider Sony, which brought out its first e-reader three years before Amazon’s but lost decisively to the Kindle and withdrew from the market in 2014. Because it failed to provide a compelling value proposition that would mobilize key components of the publishing ecosystem—authors and publishers—it could offer only 800 titles when its e-reader launched. In contrast, Amazon initially sacrificed profits, selling e-books for less than what it paid to publishers. It also invested in digital rights management to spur the growth of its ecosystem. With the support of other stakeholders, it launched with 88,000 e-books ready for download.

Third, leaders must embrace the inconvenient truth that attempts to directly control agents at lower levels of the system often create counterintuitive outcomes at higher levels, such as the stagnation of a strategy or the collapse of an ecosystem. They must avoid relying on simplistic causal models and trying only to directly manage individual behavior, and instead seek to shape the context for that behavior. For example, questions or simple rules aimed at fostering autonomy and cooperation and leveraging employees’ initiative can be more effective than top-down control in shaping collective behavior.

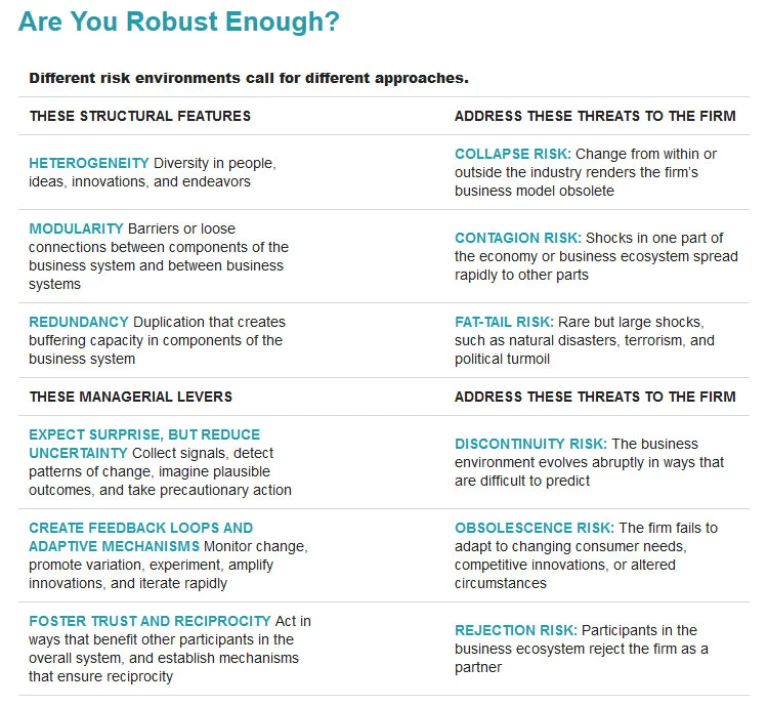

We have identified six principles that can help make complex adaptive systems in business robust. (For a related examination of complex adaptive systems in nature, see Fragile Dominion, by Simon Levin.) They derive from our study of features that distinguish dynamic systems that persist from those that collapse or decline. The first three principles are structural; they deal with the design of the system and are broadly seen in nature. The second three are primarily managerial; they deal with the application of the intelligence and intentionality provided by humans. Their key features have been observed in a wide variety of managed systems, from fisheries to global climate control agreements.

A few caveats: Each principle confers a cost and has an optimal level of application; leaders must carefully calibrate how aggressively to implement each one. Furthermore, the principles are in tension with one another; emphasizing one may require deemphasizing another. Leaders must consider how to balance the principles collectively rather than treat the application of each as a unitary goal. For clarity we will illustrate the principles one at a time, but robust systems typically exhibit many or all of their characteristics simultaneously.

Maintain Heterogeneity

Variety in the units of a CAS allows the system to adapt to a changing environment. Biologically, such heterogeneity explains why many diseases persist despite efforts to eradicate them. The influenza A virus has a high mutation rate and thus a large number of strains. Although we regularly develop resistance to the current common strains, new ones are always emerging. More generally, variation is the stuff of evolutionary adaptation: Heterogeneous components make up the reservoir on which selection acts.

In a business CAS, leaders must ensure that the company is sufficiently diverse along three dimensions: people, ideas, and endeavors. This may come at the cost of short-term efficiency, but it is essential to robustness. One obvious starting point is to hire people with varied personality types, educational backgrounds, and working styles. But even amid such diversity, employees are typically reluctant to challenge the dominant business logic, especially if the firm has been successful. An explicit cultural shift and active managerial support may be needed to encourage people to risk failure and create new ideas; indeed, the absence of mistakes is a clear indication of missed opportunities and ultimately of enterprise fragility. Many Silicon Valley firms celebrate productive, or “learning,” failures (think of the mantras “Fail fast” and “Fail forward”), which contribute to their success.

Fujifilm exemplifies robustness through strategic heterogeneity. Its industry faced a crisis in the late 1990s, when digital photography reached the consumer market and quickly eroded demand for photography film. Fujifilm responded with a series of radical reforms to diversify its business—partnering with new companies, investing heavily in R&D, and acquiring 40 firms. What distinguished Fujifilm’s approach from that of the other industry giant, Kodak, was that the firm explored not only obvious adjacencies but also entirely new business areas, such as pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, where it could exploit its existing capabilities in chemistry and materials. It also did so to a sufficient degree. The exploratory efforts and resulting diverse offerings paid off. While the camera film market peaked in 2000 and shrank by 90% over the following ten years, Fujifilm grew; in contrast, Kodak declared bankruptcy in 2012.

Business heterogeneity is often punished by markets through the “conglomerate discount”—a markdown on the stock price relative to pure-play competitors. However, when a company experiences an environmental shock like the one Fujifilm and Kodak faced, heterogeneity is a key source of robustness.

Sustain Modularity

A modular CAS consists of loosely connected components. Highly modular systems impede the spread of shocks from one component to the next, making the overall system more robust. We see this effect in nature. For instance, occasional local forest fires help maintain modularity by creating areas of lower combustibility. When such fires are artificially suppressed, modularity disappears over time, opening the way for catastrophic blazes that can destroy the entire system.

The performance of Canadian banks during the global financial crisis offers a vivid example of how modularity confers robustness in business. Canada’s regulations mandated less risk-taking behavior than was permitted in the United States, thus minimizing exposure to the complex financial instruments, such as collateralized debt obligations, that created hidden connectivity across US firms and built systemic risk. Furthermore, Canadian banks had a higher ratio of retail deposits, which are generally more dependable than other sources of funding. Thus a weakness in one part of the system was less likely to cause runs in other parts. Finally, the banks had relatively limited investments in foreign assets, which protected them from contagion elsewhere in the global financial system. Thanks to this modularity, Canadian banks emerged from the crisis largely unscathed. None needed recapitalization or government guarantees.

In a business context modularity always brings trade-offs: Insulating against shocks means forgoing some benefits of greater connectivity. Within a company, tight connections across regions or businesses can enhance information flows, innovation, and agility, but they tend to make the company vulnerable to severe adverse events. In the broader ecosystem, integration with other business stakeholders can bolster effectiveness in similar ways, but interdependence also amplifies risk. Because the benefits of risk mitigation are subtle and latent, whereas efficiency gains are immediate, managers often overemphasize the latter.

Despite the trade-offs, modularity is a defining feature of robust systems. A bias against it for the sake of short-term gains carries long-term risks.

Preserve Redundancy

In systems with redundancy, multiple components play overlapping roles. When one fails, another can fulfill the same function. Redundancy is particularly important in highly dynamic environments, in which adverse shocks are frequent.

Consider how the human immune system leverages redundancy to create robustness against disease. We have multiple lines of defense against pathogens, including physical barriers (the skin and mucous membranes), the innate immune system (white blood cells), and the adaptive immune system (antibodies), each of which consists of multiple cellular and molecular defense mechanisms. In healthy people these redundant mechanisms act in concert, so when one fails, others prevent infection. AIDS is so deadly because it effectively destroys the second and third lines of defense, removing redundancy. (The immune system also shows that multiple principles are usually at play in robust systems: It exhibits not only redundancy but also heterogeneity and modularity of defense systems, and it has feedback loops that permit adaptation.)

Businesses often impugn redundancy, treating it as the antithesis of leanness and efficiency. This has led to some disastrous outcomes. In the 1990s, when Ericsson was one of the world’s leading mobile-phone manufacturers, it adopted a single-source procurement strategy for key components. In 2000 a fire incapacitated a Philips microchip plant, and Ericsson was unable to switch rapidly to another supplier. It lost months of production and recorded a $1.7 billion loss in its mobile-phone division that year, which resulted in the division’s merger with Sony.

How can businesses implement redundancy while avoiding prohibitive expense or inefficiency? First, managers should identify the stakeholders—they might be suppliers or innovation partners—on which the business is most dependent. For Ericsson, that set would have included Philips. Next, they should determine the feasibility of creating redundancy to reduce risk. Often this will involve developing new partners, which necessitates careful consideration of the trade-offs involved. Toyota creates redundancy in a highly cost-effective manner. In 1997 a fire at Aisin Seiki, its sole source of P-valves, threatened to halt production for weeks. But Toyota and Aisin were able to call on more than 200 partners and resumed full production in just six days. Although only Aisin had the experience and knowledge for the production of P-valves, Toyota’s tight network of collaborators had, in effect, created redundancy and conferred robustness.

Let’s turn now to the power of human agency, in the form of three managerial principles that can make complex adaptive systems in business more robust.

Expect Surprise, but Reduce Uncertainty

A key feature of complex adaptive systems is that we cannot precisely predict their future states. However, we can collect signals, detect patterns of change, and imagine plausible outcomes—and take action to minimize undesirable ones.

The Montreal Protocol, which established global rules for protecting the ozone layer, illustrates these capabilities. Scientists from many countries came together to analyze the human health impacts of ozone layer depletion by chlorofluorocarbons and propose interventions. Because the atmosphere is a complex adaptive system, the precise impact of human activity couldn’t be predicted. Nevertheless, by presenting rigorous evidence of the potential consequences of further degradation, the scientific community built a consensus for action. The United Nations called the protocol “perhaps the single most successful international environmental agreement to date.” Nature does not allow us to predict the future, but it can reveal enough for us to avert disasters.

In business systems few things are harder to predict than the progress and impact of new technologies. But it can be worthwhile to actively monitor and react to the activities of maverick competitors in an effort to avoid being blindsided. Companies that do this follow a few best practices. First, if they are incumbents, they accept that their business models will be superseded at some point, and they consider how that may happen and what to do about it. Second, they understand that change often comes from an industry’s periphery—from start-ups or challengers who have no choice but to bet against incumbents’ models. Third, they collect weak signals from the smart money flows and early-stage entrepreneurial activity that constitute those bets against their models. Fourth, they practice contingent thinking: Rather than posing the unanswerable question of whether this or that company or technology will succeed, they ask, If the maverick’s idea worked, what would be the consequences for us? Finally, they take preemptive action against such threats by replicating the idea, acquiring it, or building defenses against it.

The consumer optics firm Essilor, which has grown its top and bottom lines at double-digit rates in a mature low-growth industry for the past several decades, exemplifies this approach. “Technology is critical but unpredictable, and we can’t control it or do it all ourselves,” CEO Hubert Sagnières told us. “But we can scan systemically for threats and opportunities, jump on them decisively, and build capabilities to exploit them.”

This approach led Essilor to acquire Gentex in 1995, making it the world leader in polycarbonate lenses. It also enabled the firm to access and exploit digital-surfacing technology, which had been identified as a major strategic threat some years earlier, by acquiring Johnson & Johnson’s Spectacle Lens Group in 2005. A major competitive threat was neutralized, and an $8 million business operating at a loss was turned around and grown into a $50 million operation with 35% margins.

Create Feedback Loops and Adaptive Mechanisms

While heterogeneity provides the variety on which selection operates, feedback loops ensure that selection takes place and improves the fitness of the system. Feedback is the mechanism through which systems detect changes in the environment and use them to amplify desirable traits. The fact that selection occurs at the local level implies, paradoxically, that some lack of robustness at lower levels may be necessary for robustness in the larger system. That is, the system must destroy order locally to maintain its fitness at higher levels.

In nature, mutation and natural selection—the variation, selection, and propagation of genes that contribute to reproductive success—is an autonomous process. In business the analog is a predominantly “managed” activity. The variation, selection, and propagation of innovations happen only when leaders explicitly create and encourage mechanisms that promote those things. In fact, mainstream management thinking, as taught in many business schools, may actively suppress the intrinsic “variance” and “inefficiency” associated with iterative experimentation. Yet the cultivation of this adaptive capability is now essential for companies that may have managed themselves for decades using only analysis and planning.

How can a company implement the process of iterative innovation?

First, it must detect the right signals from across the organization. This is not trivial. There is always some distance between the local actions of an employee or a business unit and the macrolevel outcomes they produce. We often don’t know which behaviors are worth strengthening and which should be discouraged. Still, frontline employees have valuable information that typically isn’t transmitted and amplified. Leaders need to engage with those employees to discover innovations that could improve robustness. That’s why Japanese manufacturing managers often go to the gemba (the “real place,” such as the factory floor) to glean fresh and rich information. By interacting directly with employees there, they can identify challenges and innovative solutions visible only at the local level.

Second, the organization must translate those signals into action. This may seem self-evident, but large companies often find themselves unable to implement this crucial second step because it may require diverting resources from the dominant product or business model and perhaps allowing underperforming products, businesses, and employees to fail more quickly. James Cannavino, IBM’s chief strategist in the early 1990s, notes that strategic planners were aware of the rise of PCs and the increasing importance of software long before the company faced a crisis. But the mainframe business was so profitable that they weren’t inclined to translate their insight into a definitive shift to personal computing. Ambidexterity—the ability to simultaneously run and reinvent the company—requires effective feedback loops and is critical to robustness in changing environments.

Tata Consultancy Services operates in the technology services space, which is characterized by unpredictability in both the technology itself and its application by large organizations. Recognizing that it needed to optimize for adaptability, the firm instituted its 4E model of experimentation—explore, enable, evangelize, and exploit. TCS explores by placing many small bets and scaling them up or down on the basis of market feedback. The strategy is enabled by heavy investments in analytic and knowledge management capabilities. Successes are evangelized within the organization, thereby enabling TCS to fully scale and exploit them. The company has had spectacular results, growing from $20 million in revenue in 1991 to $1 billion in 2003 and more than $15 billion in 2015. Its rise reflects an ability to rapidly adapt in a dynamic sector where many large rivals have faltered.

This is not to say that the tighter the feedback, the better. If the feedback cycle becomes too short or the response to change is too strong, the system may overshoot its targets and become unstable. For example, financial regulatory systems tend to swing between overregulation and underregulation, making equilibrium impossible. As with the other principles, calibration is essential.

Foster Trust and Reciprocity

In society, complex adaptive systems require cooperation in order to be robust; direct control of system participants is rarely possible. Individual interests often conflict, and when individuals pursue their own selfish interests, the system overall becomes weaker, and everyone suffers. This is the quandary of so-called collective action problems: Individuals lack incentives to act in ways that benefit the overall system unless they benefit in immediate ways themselves. Trust and the enforcement of reciprocity combine to provide a mechanism for organizations to overcome this quandary. (Indeed, this was key to the success of the Montreal Protocol.)

The Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom studied situations in which users of a common-pool resource, such as a fishery ecosystem, are able to avoid the “tragedy of the commons,” whereby public resources are overexploited to the eventual detriment of everyone involved. Her insight was that trust, along with variables such as the number of users, the presence of leadership, and the level of knowledge, promotes self-organization for sustainability. It allows users to create norms of reciprocity and keep agreements.

An Increasingly Complex Environment

An Increasingly Complex Environment

- Businesses face ever more diverse environments, which are often harsher, less predictable, and more malleable than classic environments. (For a more comprehensive discussion, see Your Strategy Needs a Strategy, by Martin Reeves, Knut Haanaes, and Janmejaya Sinha.)

- Technological innovation has increased the pace and impact of change. The diffusion rate of products from invention to saturation has risen dramatically. For example, although it took the telephone 39 years to go from 10% to 40% penetration in the US market, mobile phones achieved that degree of penetration in six years, smartphones in three. As a result, according to our research on all US public companies, firms move through business life cycles twice as quickly, on average, as they did 30 years ago. That means products and business models become obsolete more quickly and companies must adapt more rapidly. Businesses that fail to keep pace may lose their competitive viability, as the fate of Borders, Polaroid, and many others attests.

- Businesses are more interconnected than ever before. Multinational companies move goods, services, and capital around the world. Their activities link markets globally, driving increased correlation across stock markets. In addition, distinct ecosystems of partner companies have become increasingly common, with firms forming interdependencies that cross industry boundaries. As the required rate of innovation rises, firms rely on one another more. These connections can create tremendous vitality in the economy, but they increase the risk of shocks capable of cascading throughout the system.

To leverage the power of trust, leaders should consider how their firms contribute to other stakeholders in their ecosystem. They must ensure that they are adding value to the system even as they seek to maximize profits.

Novo Nordisk’s approach to new markets illustrates how this can work. Let’s look at the firm’s entrance into the Chinese market for insulin. The company established a Chinese subsidiary in the early 1990s, well before there was widespread awareness of or established treatment protocols for diabetes in China, or even many physicians who could diagnose it. Novo Nordisk built relationships with other stakeholders in diabetes care, establishing partnerships with the Chinese Ministry of Health and the World Diabetes Foundation to teach the medical community about diagnosis and management, and facilitating more than 200,000 physician training sessions. It also reached out to patients through grassroots campaigns and developed support groups to establish itself as more than just a provider of insulin. Finally, it demonstrated its local commitment by building production sites and an R&D center in China.

These efforts not only developed the market—they built trust between the company and other stakeholders. And they paid off. Novo Nordisk now controls about 60% of China’s enormous insulin market. Making a clear commitment to other stakeholders and the social good enhanced the robustness of the firm and strengthened the broader CAS in which it is nested.

Rising corporate mortality is an increasing threat, and the forces driving it—the dynamism and complexity of the business environment—are likely to remain strong for the foreseeable future. A paradigm shift in managerial thinking is needed. Leaders are used to asking, “How can we win this game?” Today they must also ask, “How can we extend this game?” They must monitor the changing risk environment and align their strategies with the threats they face. Understanding the principles that confer robustness in complex systems can mean the difference between survival and extinction.

The Biology of Corporate Survival appeared in the January–February 2016 issue of Harvard Business Review. It is republished here with permission. Illustration by Janine Rewell.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.