Today, after six years of bloody civil war, more than half of Syria’s 11 million people have been displaced. Six million people have fled to neighboring countries or sought asylum in Europe. And the crisis shows no signs of abating. With refugee needs outpacing resources, humanitarian aid agencies and donors are asking urgent questions: How can we be even more effective? Can we stretch our funds further?

The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP)—which provides emergency food assistance to approximately 4 million people within Syria and 1.5 million Syrian refugees in neighboring countries—recently commissioned a study to explore the effectiveness of its food assistance efforts on behalf of Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. Specifically, the study explored which modality was more effective in delivering food security for refugees: electronic food vouchers or unrestricted cash. (The full WFP report, “Food-restricted voucher or unrestricted cash? How to best support Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon?” is available as of May 9, 2017.)

The results of the study were clear. Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon who received unrestricted cash had similar or better food security than those who received food vouchers. And cash did not cause harm in terms of unintended use of the assistance, effects on family dynamics, or other negative consequences that critics often raise. Given the protracted nature of the crisis and the challenges of maintaining funding over such an extended period, the study’s findings offer valuable insight for humanitarian aid organizations as they gauge how best to support refugees in this context.

Study Design

The study’s designers randomly selected and assigned about 3,100 households of Syrian WFP beneficiaries in Jordan and Lebanon to three different groups differentiated by how they accessed the WFP assistance uploaded to their electronic card:

- Members of one group used the card as an electronic food voucher at WFP-affiliated stores.

- Members of a second group withdrew unrestricted cash from ATMs.

- Members of the third group had the choice of using electronic food vouchers, unrestricted cash, or a combination of the two.

The study, which was conducted from March through May 2016 and again in October 2016, tracked the impact of the different assistance modalities across multiple dimensions:

- Changes in food security, basic needs, and coping strategies

- Impact on daily life, household dynamics, and gender roles

- Household bank withdrawals, retail transactions, expenditures, and spending patterns

- Fluctuations in food prices at WFP-contracted stores and non-WFP stores

- Beneficiaries’ preferences and overall satisfaction

The study’s postdistribution monitoring occurred in three phases in Jordan (March, May, and October 2016) and in two phases in Lebanon (May and July 2016). The study took into account both quantitative data (from multiple household surveys, bank records, and retail transactions, among other sources) and qualitative information (drawn from personal focus group discussions with beneficiaries on topics such as family dynamics, shopping patterns, and tradeoffs in food quality versus quantity). Together, Jordan and Lebanon accounted for approximately 75% of the WFP’s 2016 food voucher programs in the region. The study was limited to families living in host communities; it excluded people living in refugee camps.

Cash-based assistance is not appropriate for every country, and delivery modalities must be context specific to be effective. Jordan and Lebanon are middle-income countries, with functioning and accessible markets—not unlike Syria before the civil war. Cash-based assistance can work well with people who are accustomed to life in a cash system, but it may be less effective in developing nations with limited market functionality, in failed states, and in situations where food shortages are chronic. Although results may vary depending on each region’s unique socioeconomic and market conditions, the study’s findings offer important insights to help inform and shape the debate over how best to support populations in need. The following are among the report’s key findings.

Cash Boosts Purchasing Power and Food Security

Overall, compared with food-restricted vouchers, cash assistance delivered superior or equivalent food security. This is because people who received cash could exercise greater purchasing power, in several ways.

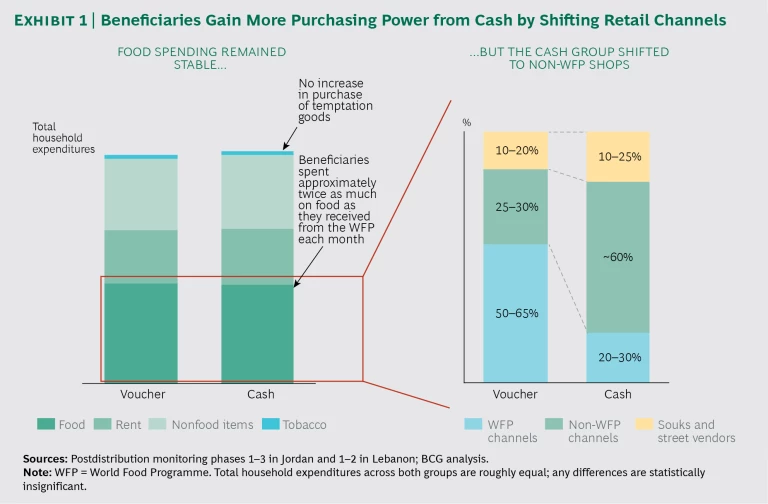

Because they withdrew money from ATMs, cash recipients could shop at all vendors—including souks and street vendors—not just at WFP-affiliated stores. (See Exhibit 1.) And because they could shop when and where they chose, beneficiaries could tailor their purchases to take advantage of sale items and stretch their very limited budget. Hunting for bargains in different shops could yield price advantages of 8% to 17%. One beneficiary put it this way: “With cash you can benefit from more savings, find the best promotions, and buy at the lowest prices. If you organize well, you can have more food for the same amount of money.”

With access to cash, beneficiaries shopped for food more frequently, which boosted their access to fresh produce and perishables. Under the voucher program, people tended to purchase in bulk once or twice per month, which naturally led to higher consumption of dry and canned goods. This trend was particularly pronounced among households located far from WFP-affiliated stores, since those people often had to pay for taxis to get their groceries home, and therefore had strong financial motivation to keep their shopping trips to a minimum. But with easy access to local stores, people could buy fresher, more healthful foods, increase their diet’s variety, and save money. A female head of household from Mafraq governorate in Jordan said, “In my case, the variety of products bought has increased. We buy more dairy products. Instead of buying expensive cheese at the mall, I now buy milk and make my own cheese.”

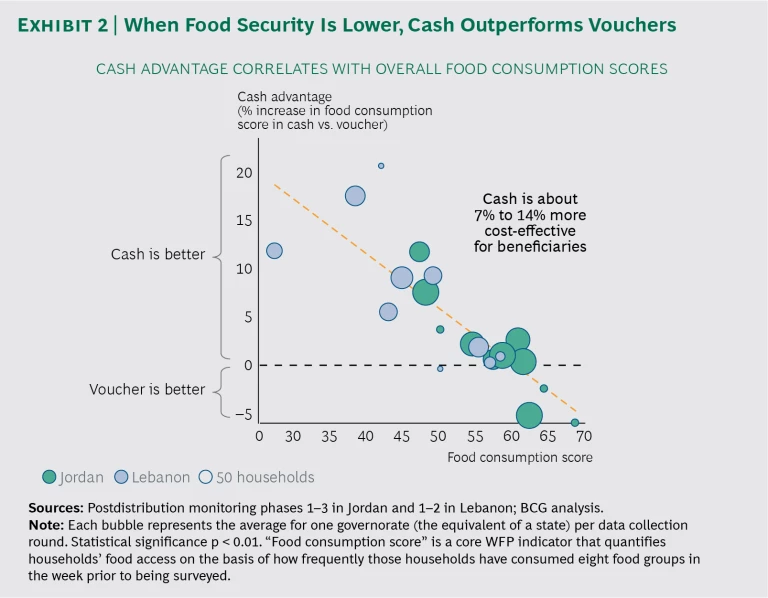

The study revealed an interesting dynamic with regard to food quantity versus food quality in people’s purchasing decisions. In situations with a lower baseline of food security, we observed a “coping” mentality. When times were tough, beneficiaries found ways to leverage the flexibility of cash to compare prices and hunt for bargains. In this way, they were able to boost the quantity of food they purchased overall—in essence, buying more of the same.

As their baseline for food security strengthened and they consistently met their basic food quantity needs, beneficiaries developed more of an “upgrading” mentality, bargain-hunting for food they perceived to be of higher quality. This dynamic is far less evident with the food voucher group, whose bargaining capabilities and choice of stores are relatively limited. (See Exhibit 2.)

Recipients of unrestricted cash and recipients of food vouchers spent approximately double the WFP assistance value on food, but those receiving cash also reported that it allowed them to manage their cash flow more effectively in the event of unexpected crises (such as to manage medical costs), without altering their overall food expenditures. As one male beneficiary from Northern Lebanon said: “Cash is helping us ease the burden of other needs. While we end up spending the same amount on food at the end of the month, the liquidity is giving us some flexibility in meeting other needs.”

Cash Does No Harm

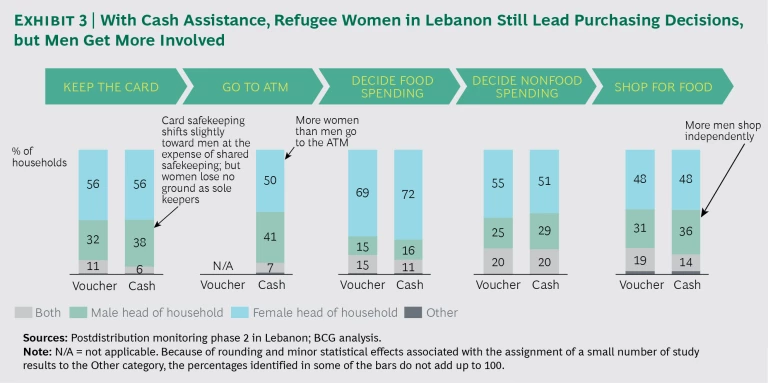

Having greater access to cash raised the possibility that beneficiaries might face greater risks in certain respects, including theft, mistreatment, increased debt, unintended uses of the assistance, or household disagreements. Across the board, however, the cash group fared just as well as the voucher group on these dimensions. Cash recipients did not report a higher incidence of theft, mistreatment, or increased debt. Furthermore, the switch from voucher to cash seems not to have led to any increase in household disagreements nor to have altered household dynamics. In approximately 60% to 70% of households, women are the primary decision-makers about food purchases—and women’s decision-making power did not diminish significantly in households that received unrestricted cash. (See Exhibit 3.)

Cash also had no discernible effect on overall spending behavior. Beneficiaries typically spend approximately 40% of their total budget on food, 30% on rent, and 30% on nonfood items. Spending on basic needs, such as rent, health care, and education, was similar for the cash group and the voucher group. The availability of cash did not lead to different purchasing behavior with regard to temptation goods such as tobacco.

Beneficiaries Preferred Cash

When given the choice to receive WFP assistance through either unrestricted cash or food vouchers, more than 75% of households preferred cash. The cash recipients appreciated the flexibility to shop when and where they chose, the increased ability to negotiate for lower prices, and the opportunity to get more variety and value for their money. What’s more, cash provided a sense of dignity and empowerment to beneficiaries. It allowed them to avoid the separate, long lines that WFP voucher recipients often encountered in the first week after their e-cards were uploaded, and they were able to blend in with people from their host communities. One beneficiary described the sense of dignity that comes with cash this way: “I am happy because I feel like a normal local citizen in the shop.”

The 15% to 20% of beneficiaries in the ‘choice’ group who opted to stick with vouchers offered two explanations for their choice. First, the voucher gave them a strong sense of food security: they knew that they would dedicate the full WFP assistance amount to food each month, and they appreciated the discipline that it brought to their spending. Second, for some households, lack of proximity to an ATM posed a logistical challenge. Nevertheless, beneficiaries who initially were randomly selected to receive assistance in the form of cash, subsequently developed the strongest preference for cash (90%)—suggesting that experiencing cash was an important driver for preferring it.

For Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon, cash can offer an effective alternative to food vouchers. Not only did cash do no harm, but refugees who received unrestricted cash found that they could buy food in greater quantity and variety, and they reported a greater sense of empowerment. Cash provided marked advantages for beneficiaries, especially when constraints on funding limited overall assistance to an unusual degree. These findings provide potentially useful insights for other aid agencies as well. By understanding how different aid delivery modalities impact the lives of beneficiaries, and using this evidence-based research to guide operational improvements, humanitarian aid agencies can ensure the highest possible positive social impact.