This article is a chapter from the BCG report, The Most Innovative Companies 2018: Innovators Go All In On Digital.

Explore the Full Report

Explore the Full Report

- Innovation in 2018

- How Digital Transforms Innovation Strategy

- A Digital Overhaul for Innovation Operations

- Organizing for Digital Innovation

- The Most Innovative Companies Over Time

Digital organizations are different. Consider Tesla, a digital native that has been among the top ten companies on the last three BCG lists of the most innovative companies and that ranked number six in 2017. Tesla looks nothing like other auto OEMs. Its structure, rather than being functionally divided and hierarchical, is organized around small, agile-empowered teams that comprise a program executive who ensures cross-product integration; a product owner who is responsible for architectural definition, customer success criteria, and feature resource needs; feature developers; and end-to-end quality engineers.

The company’s flat structure supports cross-functional teaming and communication. Each team works on one integrated project plan at a time with a clear owner. The project leader has the authority to set cross-functional resource levels. The teams themselves are organized to reduce coordination complexity, and they are accountable to a program, not a function. Customers are involved in testing and improving products; their feedback influences feature changes and priorities. Incentives are designed to motivate cross-functional interaction.

With no legacy structures to constrain it, Tesla organized itself for innovation. The question for traditional companies in all sectors is how to transform their organizations in order to achieve the speed, agility, and success of native digital innovators.

Digital Organization Design Principles

Digital innovations take many forms—new products and services, more efficient and high-impact operations and processes, even radically different business models, as we explore in related articles. (See the companion articles “How Digital Transforms Innovation Strategy” and “A Digital Overhaul for Innovation Operations.”) But if such innovations are to take root and thrive, they will need a digitally capable organization to make them work. New products designed for customer journeys in financial services, for example, are meaningless if a company cannot engage customers and access data digitally. Features for connected cars will not operate without a connected organization to make them function. Automated services for industrial equipment won’t work unless the company is equipped to process digital data from the IoT. Digital innovation and digital organizations are codependent and intertwined.

Digital organizations are built on a set of design principles. These organizations are:

- Customer-Centric. They focus all aspects of the business on customer needs and wishes.

- Agile. They adhere to short response and implementation times in both decision making and resource allocation.

- Experimental. Digital organizations’ business models foster experimentation; they are built to try, fail quickly, and improve. When something works, they scale up fast.

- Lean, Simple, and Standard. They aspire to have standardized structures, units, and processes as well as clear roles and responsibilities. Simplicity is a central consideration in decision making.

- Focused on Operational Excellence. Digital organizations champion efficiency, lean techniques, competitive cost structures, and continuous improvement. They maintain a high degree of organizational discipline.

- Empowered and Accountable. They empower managers to take action; they monitor performance and hold managers accountable; and they focus on a small number of simple and clear KPIs.

- Cross-Functional. Their teams purposefully combine all relevant types of expertise, both digital and business-specific. Digital organizations avoid functional silos so that ideas, expertise, and data can be easily shared and acted on.

From Principles to Practice

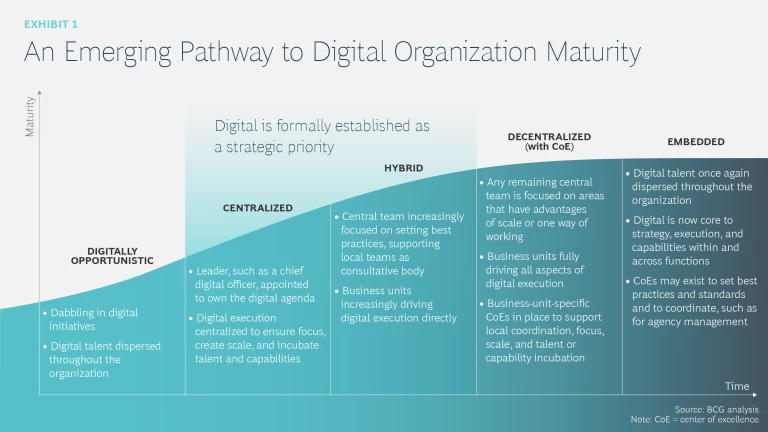

Digital’s impact is still developing in many industries, and companies continue to wrestle with how to put digital principles into organizational practice, including with respect to innovation. Yet, in our work with clients, we are beginning to see a common pathway to maturity emerge. (See Exhibit 1.)

Initially, many companies are digitally opportunistic, experimenting with digital initiatives. Typically, they do so at the business unit level because these units are closest to customers and are often the first to feel the need for digital marketing and engagement, e-commerce, and the like. But the efforts typically are fragmented, lacking in resources, and conducted without an end-to-end corporate view of how the company should harness digital technologies.

When companies realize that digital needs to be integral, if not central, to their strategy, they start to centralize digital development and execution to heighten focus, create scale, and incubate talent and capabilities. Often they appoint a leader, a chief digital officer (CDO), for example, to drive the digital agenda. The next phase of development involves a hybrid digital function with a central team focused on setting best practices and supporting local teams as a consultative body, while the business units drive digital execution. At first, the business units drive most aspects of digital execution with centers of excellence (CoE), which support local coordination, focus, scale, and incubation of talent and capabilities. At maturity, the role of the CoEs diminishes as digital capabilities are embedded throughout the organization and digital technologies and ways of working become core to both strategy and execution.

A Digital Innovation Unit

The split between centralized and decentralized digital development is reflected in how companies approach innovation generally. In our survey, almost 30% of all respondents said that a centralized organization controls and drives innovation at their companies; 35% reported that a centralized organization drives research and passes the results to the business units; and 29% said that the business units drive their own innovation with support from a centralized organization. A more pronounced preference emerged among strong innovators, where innovation tends to be more centralized. More than 70% of strong innovators (compared with 50% of weak innovators) reported that either a centralized organization controls and drives innovation or the centralized organization drives research and passes the results to the business units.

In our experience, a centralized digital innovation unit has a mix of several critical responsibilities. It creates a digital innovation roadmap that guides the digitization of the company’s innovation function and monitors progress. It manages cross-functional digital projects. A chief data officer is responsible for using external and internal data for improved decision making, including developing tools, methodologies, and platforms; identifying and prioritizing data sources; building a data engine to gain insights; and developing and managing data policy. A customer experience team seeks to create superior and seamless customer experiences across digital and nondigital channels. This includes mapping customer journeys, designing customer interfaces, and putting in place an e-commerce strategy, if needed. This team also helps business units implement digital tools and best practices.

A team responsible for driving digital innovation brings in the technology. It manages relations with the startup community, including seed investments; fosters internal innovation; oversees digital incubators, accelerators, and labs; and supports deployment of innovation initiatives. Finally, a partnerships team develops an ecosystem of business development ventures that can generate new sources of revenue.

Companies slot this type of unit into their organizations in different ways and places. In some instances, the unit reports directly to the CEO. At one global consumer goods company, a team under a vice president for digital transformation, reporting to the CMO, operates as a digital marketing CoE responsible for training and sharing best practices across the brand teams. A separate e-commerce team oversees an e-commerce CoE, as well as a big data and analytics operation. Another consumer company has a central digital acceleration team, to which top talent from the business units must apply. Successful candidates spend eight months executing projects, after which they return to their home markets and transfer the acquired capabilities to their business units. At Apple, the late Steve Jobs famously handpicked the top 100 employees to drive brainstorming and idea generation.

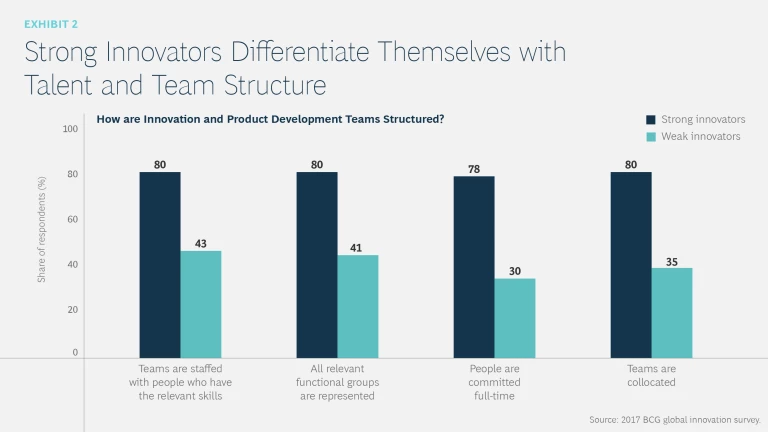

One hallmark of digital insurgents is talent: they hire strong, committed people who relish experimentation. These hires are also willing to work hard, giving the company their all for a possible successful outcome. Our research shows that strong innovators are much more likely than weak innovators to establish teams that are staffed with people who have the appropriate skills, to make sure that all relevant functional groups are represented, and to have people who are committed full-time. (See Exhibit 2.)

Renault’s response to digital disruption in the auto industry has been to create its own “digital factory.” This unit drives customer-centric product development, has agile teams working to accelerate and secure digital value (by developing proofs of concept, for example), coordinates digital activities across functions, leads the implementation of digital initiatives, and scouts the organization for digital innovation.

The Digital Leader

Many companies find that they need a CDO to oversee both digital innovation and the digital transformation of the organization. This digital leader can be pivotal to a company’s progress along the digital maturity curve. The CDO’s key attribute is not a technical background, though that is certainly important. Rather, it is the ability to understand the power of the full range of digital technologies, from data to mobile to artificial intelligence, and the impact that they can have on products, services, and business models. More specifically, a digital leader should:

- Have breadth: a deep understanding of both technology and the business and a clear vision of how technology can affect the top and bottom lines.

- Have a vision: knowledge of the key technology and market trends and how they shape the need for technology capabilities and talent now and in the future.

- Be culturally adept: capable of managing cultural differences among digital and business teams and equipped to push a culture shift across the broader organization.

- Be adaptive and flexible: able to monitor the progress of the transformation and adjust digital efforts to changes in the environment, such as in technology development, competition, and consumer behavior.

- Be collaborative: capable of bringing together leaders from different business units and driving alignment on transformation priorities and timing, resulting in cooperation around a common vision.

The scope of the digital leader can vary from a targeted to a comprehensive transformation, depending on the company’s digital strategy. Companies pursuing a targeted strategy concentrate on a few areas and on the enablers identified as most critical to the organization’s digital strategy. This is a common model among large organizations because of the complexity of their existing operations, the need to prioritize resources, and the desire to see new capabilities deliver actual value before committing further resources to the effort.

A comprehensive transformation focuses on all aspects of digital and ensures one coordinated strategy and execution across the enterprise (as opposed to each function pursuing its own priorities). We see this model being followed more commonly at smaller, newer companies that have employed digital technologies and approaches from the outset, as well as in industries where digital already has an established, proven track record.

A New Approach to Organization

Digital innovations can lead to the need for completely new organizational thinking. Consider, for instance, an athletic-shoe company that has long sought to produce a vast array of shoes for consumers to choose from at the lowest possible price, but which now seeks to offer personally customized shoes to every customer who wants them—because digital technologies make that level of personalization possible.

Such a fundamental shift in strategy has big implications for every stage of the value chain, from sourcing materials and components through production and assembly to marketing, sales, shipping, and delivery. The assembly line may no longer work in a linear fashion, starting with raw materials and ending with finished products. Workers may no longer perform the same function repeatedly but instead do different things at different stages. Traditional cost considerations, such as labor, may no longer dictate factory location. There are opportunities for digital innovation at every step, but only if the organization and the people it comprises are educated to think in a very different way about how shoes are produced and sold.

Which Road to Take?

Generally speaking, we see companies taking one of two paths to digital transformation. One is the measured and deliberate transformation journey—in which digital initiatives and the transformation itself are developed by internal leaders and talent over time. The trouble is that changes in digital technologies—and the companies applying them—occur too quickly for this approach to be effective; even as companies transform, they are already falling behind. The other path is the leapfrog approach, in which companies aggressively search for external leaders and talent and scale up their in-house technology capabilities as quickly as they can. These companies accept the risk of an initial culture clash between new and existing teams as part of the price of change.

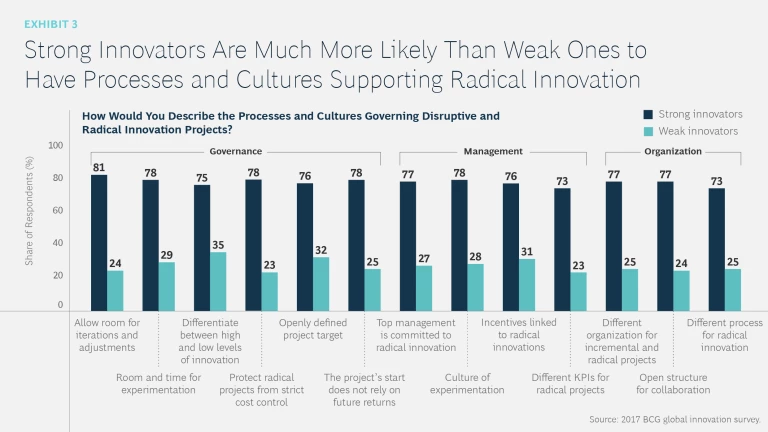

Data from our survey shows that support for a more radical approach to innovation is getting stronger. Moreover, by wide margins, strong innovators are much more likely to pursue disruptive or radical processes and cultures governing innovation projects. (See Exhibit 3.)

These companies understand that technological advances, like time, wait for no one—and that the need to transform their innovation functions, as well as their broader organizations, for the digital world is urgent.