Rail is the most sustainable mode of transport. Increasing its share of passengers and freight is critical to achieving net-zero goals.

No form of mass transport has more potential to aid in the fight against global warming than rail. It is one of the most energy-efficient transport modes, responsible for 9% of global motorized passenger movement and 7% of freight shipping—but only 3% of transport energy use, according to the International Energy Agency. It uses 80% less energy than trucks per ton of freight carried and holds a four-to-one advantage over cars in terms of its emissions intensity. As a result, rail accounted for just 4% of the transport industry’s global emissions in 2019.

Unfortunately, despite its major role in helping the world reach the Paris Agreement’s emissions reduction goals, rail has been losing share to higher-polluting transport modes in most major markets across the globe. Indeed, the ongoing shift in freight transport from bulk shipping to container-based intermodal transport, particularly for consumer goods, may continue to favor trucks over rail. And surveys indicate that people who have sought the protection of their cars during the COVID-19 pandemic may be reluctant to return to public transport, even as the threat passes.

There is an essential environmental case for reversing rail’s loss of market share—and a strong business case as well. As sustainable as rail transport is now, there is still considerable room for improvement through the development of alternative drives, greater operational efficiency, increased dependence on renewable energy, and more. Governments around the world are already making plans to increase rail’s sustainability. For them, greater sustainability means not just a smaller carbon footprint but also lower costs throughout their operations and supply chains. As a result, passenger and freight customers looking to reduce their own carbon footprints and costs will likely find rail increasingly attractive.

In short, greater sustainability is key to rail’s future growth. But that growth will require new technologies and further support from all stakeholders, including policymakers, investors, suppliers, and rail service providers themselves. Here’s how to get on board.

OFF THE RAILS

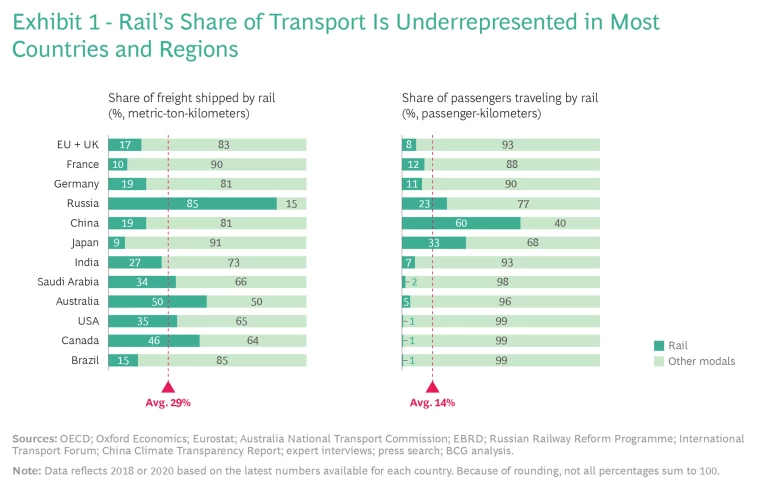

Recent data on the state of the global rail industry is not encouraging. In most countries, rail is underrepresented in terms of freight carried (measured in metric-ton-kilometers) and passenger-kilometers traveled (see Exhibit 1). And while there are exceptions, it has shown little signs of growth in recent years.

Between 2000 and 2018, passenger and freight rail in Europe have been essentially stagnant, falling by 1 and 3 percentage points, respectively. In India, freight and passenger share decreased by 10 percentage points, despite the country’s efforts to increase investments in rail. And while freight in the US managed to increase its share by 4 percentage points, passenger transport remains insignificant.

The most notable exceptions are China and Australia. Transport gained 23 percentage points during the near-two-decade period in China, although freight lost 11 percentage points. The reverse is true in Australia: freight gained 17 percentage points while the share of passengers traveling by rail remains small.

To make matters worse, several trends are hindering future growth. Passenger rail travel has fallen considerably around the world since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although rail travel has returned to normal in China, it has yet to fully recover in either the US or Europe, where it is still down to 78% and 87% of prepandemic levels, respectively. And a recent BCG survey on urban mobility ranked physical distancing and cleanliness far above sustainability among respondents’ urban mobility priorities—and rail the riskiest among urban transport choices.

Freight, too, is suffering. For example, e-commerce in the US, which heavily relies on shipments by truck, has grown 18% annually since 2000—and it has exploded during the pandemic. This growth rate is far faster than that of industries such as agriculture, mining, and automotive, which typically ship goods via rail. In Europe, freight shipments by rail have been adversely affected by the structural challenges facing the steel, energy, paper, and automotive industries, among others. As a result, the volume and mixture of goods transported by train are changing.

Meanwhile, transportation providers are working hard to become more sustainable. Electric vehicles—both cars and trucks—are gaining market share; maritime companies are experimenting with alternative power sources, such as battery-electric and hydrogen drives; and even airlines are committing to sustainable fuel sources with the hope of becoming carbon neutral in coming decades. Such efforts have the potential to win over even more customers—passengers and shippers alike—as they grow increasingly concerned about their environmental impact.

SCOPING THE CHALLENGE

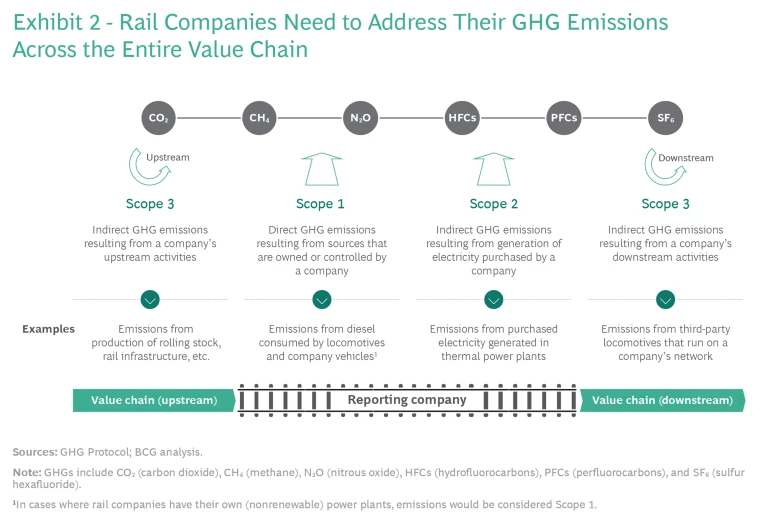

If rail is to expand and grow, it must continue to attract passengers and freight customers looking to reduce their own carbon footprints. The effort will require making progress across all three types of emissions for which rail operators are directly or indirectly responsible (see Exhibit 2):

- Scope 1 emissions encompass rail companies’ direct emissions from their trains, on-site machinery, and buildings. They are generated primarily through fossil fuels that power locomotives and company cars and trucks.

- Scope 2 emissions are created indirectly through the purchase of nonrenewable electricity that is used not just to power locomotives but also to sustain administrative operations, the operation of train stations, maintenance, and other activities.

- Scope 3 emissions include other indirect GHG emissions from rail companies’ value chains, such as the upstream emissions generated in the production of locomotives and rolling stock and the construction of rail infrastructure.

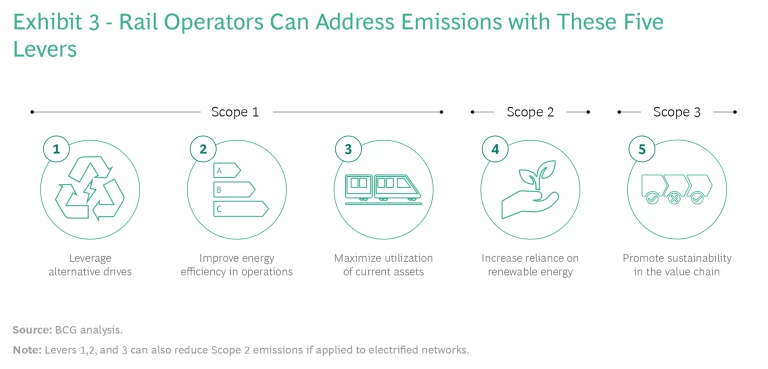

Rail companies can pull several levers to reduce their GHG emissions across the value chain. They can reduce their Scope 1 emissions in three ways: deploying cleaner alternative-drive technologies for locomotives, improving energy efficiency in operations, and maximizing the utilization of current assets. They can reduce their Scope 2 emissions by increasing the share of renewable energy purchased for their rail networks, buildings, and other activities and through cleaner locomotive drives, improvements in efficiency, and asset utilization. Companies can help lower both upstream and downstream Scope 3 emissions by actively promoting sustainability across the value chain—engaging with suppliers on decarbonization levers and setting green procurement criteria, for example (see Exhibit 3).

LEVER ONE: ELECTRIFICATION AND ALTERNATIVE DRIVES

According to the International Energy Agency, 55% of the energy consumed by the global rail industry in 2020 was generated by diesel (85% of it used to power trains), 44% by electricity, and 1% by biofuels. Reducing the Scope 1 emissions resulting from the burning of diesel—around 300 million tons of GHG emissions annually—will therefore be critical to the industry’s sustainability efforts. If global rail is to reach net zero by 2050, it must reduce its use of diesel to just 4% of the total amount of energy used, substituting either renewable electricity or some other form of propulsion.

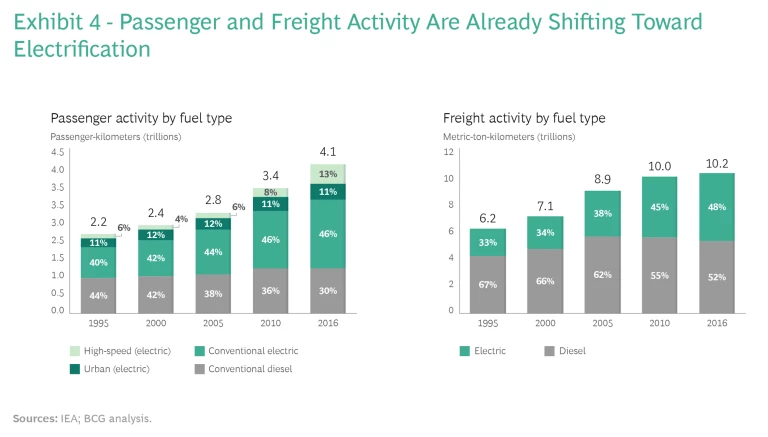

Already, operators are making the transition to electrification. As of 2016, electric locomotives were responsible for 70% of the passenger-kilometers traveled and 48% of freight-kilometers shipped (see Exhibit 4). But the share of diesel locomotives around the world remains high. About 50% of all trains in Western Europe and Asia are diesel powered, 75% in the Middle East and Africa, and a daunting 99% in the Americas.

So, the first lever in cutting the industry’s Scope 1 emissions involves either continuing to increase the use of electric locomotives—which must be powered by renewable energy so as not to increase Scope 2 emissions (see below)—or developing new drive options.

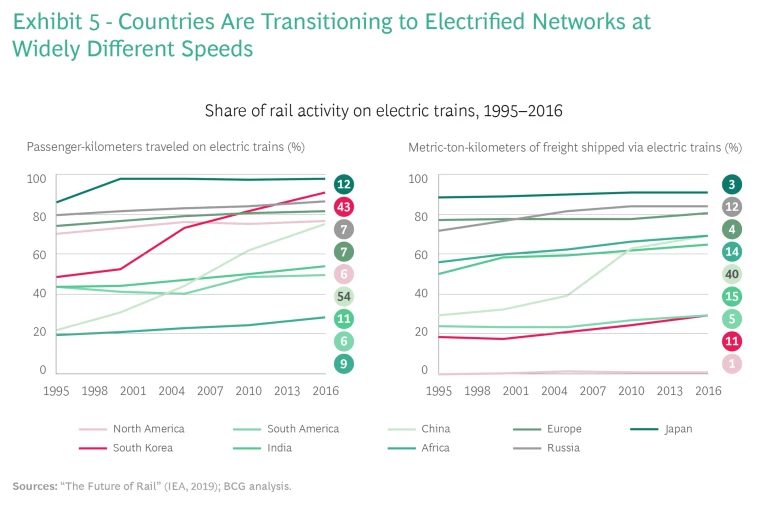

Expanding Network Electrification. While many rail operators have been moving toward electrification, the pace varies considerably by country (see Exhibit 5). Countries in Asia and Europe have significantly increased their share of electrified passenger and freight kilometers, and several are making electrification central to their net-zero transport plans. In China, for example, the share of electrified tracks jumped from approximately 20% in 2000 to around 70% in 2019. And Germany’s Electrification Plus program, launched in 2021, seeks to ensure that 100% of the country’s rail network will be traveled electrically or climate neutrally.

Elsewhere, however, efforts to electrify rail networks continue to lag. This is especially true in regions where distances are long, the infrastructure needed for electrification is very sparsely scattered, and electrification can be prohibitively expensive. The Association of American Railroads, for example, estimates that electrifying the US’s 140,000 miles of freight lines would cost millions of dollars per track-mile. And replacing even half of the nation’s 24,000 diesel locomotives would cost close to $100 billion.

Indeed, as of 2019, diesel locomotives made up 68% of the global installed base of 170,000 locomotives. Replacing them all would be too costly, given that electric locomotives cost far more than diesel and can’t be used in many regions. In short, while further network electrification is likely in regions where electrification has already taken hold, perhaps through a combination of public and private investments, it is simply not viable elsewhere.

Developing New Power Technologies. Full electrification isn’t the only solution to the problem of diesel emissions. Diesel-electric locomotives, for instance, can run either on their own diesel power or on electrified track, where available. Hybrid locomotives depend on smaller diesel engines as well as rechargeable storage systems fueled with surplus energy or energy from regenerative braking. But neither type offers the zero emissions of electric locomotives.

Another promising, but still very immature, option is the use of hydrogen gas (H2) as a power source. Its success in lowering the industry’s carbon emissions, however, will depend on several factors. The first is developing the technology and infrastructure needed to produce, distribute, and store hydrogen safely and at reasonable cost; the second is developing practical, economically viable ways of powering locomotives with hydrogen.

H2 is currently produced in numerous ways. “Gray hydrogen” is produced using natural gas as a feedstock, a process that emits CO2 into the atmosphere. “Blue hydrogen” is produced using the same process, but the resulting carbon dioxide is sequestered through carbon capture. “Green hydrogen,” the cleanest, is produced through the electrolysis of water using renewably generated electricity. Judging from the number of projects announced through the end of 2019, an estimated 4 million tons of blue and green hydrogen will be produced globally by 2028.

That still won’t be nearly enough to supply the world’s needs. Prices are expected to remain high—green hydrogen isn’t expected to become economically viable until 2030—and other industries, such as steelmaking, will be competing for the H2 available.

Additional barriers remain. Practical propulsion technologies are still under development, as is the infrastructure needed to distribute and store the hydrogen and supply railways at scale. In short, considerable capex investments will be required to make H2 a reality for the industry.

Despite the challenges, several hydrogen-powered rail projects are currently in the works. For example, a hydrogen locomotive is already in operation in Germany. A joint effort by Alstom and industrial gases company Linde, the Coradia iLint is the first train of its kind in regular passenger operation, with planned expansion to the Netherlands and elsewhere in the EU.

Alternative drive technologies will be critical to the industry’s effort to reduce its carbon emissions. The shift will take time, however, and operators must consider carefully how best to manage the transition.

LEVER TWO: INCREASING ENERGY EFFICIENCY

In addition to implementing further electrification and innovative new drives, the rail industry can reduce its Scope 1 emissions through more efficient energy use. Rail operators should consider taking advantage of six ways to increase efficiency:

- Driver Behavior. Trains run by different drivers consume very different amounts of energy, depending on how each driver uses the throttle and brake and manages speed. By training drivers on best practices, incentivizing better driving, and providing driving tips for particular routes, operators can reduce energy costs by up to 10%.

- Operational Software. A number of digital tools have recently been implemented to optimize operations for diesel and electric trains. Wabtec’s Trip Optimizer, for example, is a smart system that minimizes fuel consumption by calculating best speed, throttle, and braking for each trip. It can reduce a diesel locomotive’s annual fuel consumption by 32,000 gallons, CO2 emissions by more than 365 tons, and nitrogen emissions by 3.7 tons.

- Aerodynamics. Improved design of locomotives and rolling stock can significantly reduce drag and lower energy consumption. New designs by Alstom, Bombardier, and Siemens offer as much as 30% reduced energy consumption.

- New Materials. The combination of new composite materials and modular design has the potential to reduce energy consumption even further. Under the EU’s Shift2Rail project, a consortium of researchers, engineering firms, and suppliers are working to develop the next generation of trains, built to reduce weight while adding room for more passengers.

- Train Mechatronics. New systems are being designed that combine mechanical, electrical, and computer engineering to significantly boost energy efficiency. Produced by ABB, Siemens, and others, these systems are made cleaner thanks to regenerative braking and new propulsion mechanisms.

- Ancillary Systems. A range of options are becoming available for reducing energy consumption in noncore activities, including the use of LEDs in safety lighting and natural refrigerants in air conditioning.

LEVER THREE: MAXIMIZING ASSET UTILIZATION

Rail operator and infrastructure providers can obtain additional energy savings and achieve Scope 1 emissions reductions through more efficient asset utilization and improved construction management and maintenance activities. Options include:

- Intelligent Infrastructure. This includes a range of digital systems that use networking technology to automate signaling and switching, thus reducing delays and disruptions (caused by obstacles on the tracks, for example). Thanks to government funding, these “digital interlocking” systems are already a reality on certain lines in Germany and Switzerland.

- Smart Construction Planning. Technologies such as “digital twins” and data-driven project management software can be employed to model and manage major construction projects and ensure on-time, on-budget completion.

- Digital Infrastructure Maintenance. Condition-based and predictive maintenance software—combined with the Internet of Things, 5G data transmission, artificial intelligence, drones, and other similar tools—can significantly reduce asset downtime and maximize infrastructure utilization.

- Digital Train Operations. A range of data-driven digital systems can automate several aspects of train operations, including fleet management, timetabling, shunting and coupling, and driver assistance.

- Digital Complementary Services. Software providers now offer a number of demand-forecasting and crew-management systems intended to provide end-to-end digitization and automation of the personnel-planning process. These tools can help optimize activities such as repair, construction, and crew scheduling and dispatching. Armed with the latest software, rail providers can avoid deadheads, lengthy dwell times, and other delays.

- Digital Rolling Stock Maintenance. Data-based systems can optimize upkeep of rolling stock with predictive and condition-based maintenance technology and by automatically replenishing spare parts.

- Longer Trains. Rail providers are increasingly looking to use longer trains, especially among North America’s major freight providers. Europe, too, would benefit from longer trains. Indeed, deploying trains of up to 1,500 meters would significantly improve rail’s competitive position compared with trucks, even if restricted initially to the continent’s main corridors. Adding train cars can enhance productivity and efficiency, make better use of resources, and generate fuel savings. However, the strategy would likely require major investments in infrastructure upgrades and increase maintenance costs.

LEVER FOUR: SHIFTING TO RENEWABLE ENERGY

As noted, if the global rail industry is to reach its net-zero emissions goals, it must achieve far greater electrification of its locomotives. But even the best efforts to maintain and increase electrification will not significantly increase rail’s sustainability if the electricity the industry uses continues to be generated by fossil fuels. Running a locomotive on coal-generated electricity produces just as many GHG emissions as a diesel locomotive, though only half as much as natural gas. And even the most electrified rail networks still primarily depend on fossil fuels—80% in both Japan and India, for example.

For rail operators to reduce their Scope 2 emissions, they must significantly increase the proportion of electricity that comes from renewable sources, primarily hydroelectric, solar, and wind. And there are only two ways for rail operators to do that: purchase more renewable energy or generate their own.

Several operators are already committing to purchase more renewable electricity. In Germany, for example, Deutsche Bahn plans to buy an annual 190 gigawatts of electricity from the Amrumbank-West offshore wind farm over the next 15 years. And France’s SNCF Energy has signed a 20-year contract with EDF Renewables to buy 25 gigawatts of renewable energy generated by a 20-megawatt solar farm, opening in 2023.

In the UK, Network Rail, the primary owner of the country’s rail infrastructure, hopes to become 100% renewable by 2030. To that end, the company is working to connect solar and wind generators directly to its buildings and infrastructure, while also purchasing energy directly from third-party solar and wind farms. So far, all the electricity the company uses to power operations (excluding locomotives) comes from renewable sources.

Similarly, JR East, Japan’s largest rail operator, aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2051—not just by purchasing renewable electricity but also by working with a subsidiary to develop its own sources of renewable energy. Already, a quarter of the electricity it uses is generated renewably.

Other operators are taking matters into their own hands. The Canadian Pacific Railway built a solar energy farm installation to supply electricity for its Calgary headquarters, and Indian Railways began operating the first fully solar powered rail section in 2019.

LEVER FIVE: DECARBONIZING THE VALUE CHAIN

The rail industry’s indirect Scope 3 emissions, primarily those produced by upstream suppliers but also by downstream activities, make up a significant portion of its overall carbon footprint. Reducing these emissions will require a combined effort by all players in the global rail ecosystem. Several operators are already taking the steps needed to measure and reduce emissions across the industry’s value chain, including:

- Creating Transparency. Operators that build a baseline of GHG emissions across the value chain are able to set reduction targets for all three emission scopes and publicly report progress. By sharing this data, operators can encourage shippers and suppliers to reduce their own emissions. For example, Brazil’s MRS, a freight operator, has developed a calculator it uses as a commercial tool to attract clients by showing the emissions-reducing potential of shifting from trucks to rail. Aside from its business benefits, the calculator also stimulates the discussion regarding emissions among clients and suppliers.

- Optimizing for CO2 Reductions. Rail and infrastructure operators can work to reduce the carbon footprints of their own products and those of their suppliers. Focusing on sustainable sourcing strategies can extend these efforts throughout the supply chain. Infrabel, Belgium Rail’s infrastructure manager, recently laid sleepers made from sulfur concrete, which cost no more than traditional sleepers and release considerably fewer emissions in the production process. SBB, Switzerland’s national rail company, has been using a mixture of recycled asphalt in the construction of platforms. Using this mix instead of asphalt allows SBB to avoid 25% of the GHGs emitted in the production of new asphalt.

- Engaging Suppliers. By integrating emissions data with data from suppliers, operators can define clear emissions-based procurement standards and track suppliers’ performance, encouraging them to address their own emissions. The UK’s Network Rail, for example, determined that two-thirds of its Scope 3 emissions came from purchased goods and services in addition to capital goods. It “expects that the suppliers responsible for three-quarters of the operator’s Scope 3 emissions will have set their own science-based targets by 2025.”

- Working Within the Ecosystem. Reducing Scope 3 emissions is the responsibility of the entire rail ecosystem—operators, infrastructure provides, and suppliers alike. The entire sector must work together to set standards and commit to sustainable procurement practices, and thus create demand-side pressure to improve sustainability throughout the ecosystem. In 2015, six major rail players cofounded Railsponsible to promote sustainability across the supply chain. Membership in the consortium has grown to 15 operators and suppliers, representing more than 50 billion euros in procurement spending, 44% of which falls under Railsponsible’s sustainable procurement agreements.

- Enabling the Organization. Implementing sustainability at the operational level will require rethinking governance mechanisms to align internal incentives and manage the process. As part of Deutsche Bahn’s strategy to become climate neutral by 2040, the company enlisted 200 environmental coordinators to oversee the implementation of green projects. These coordinators work closely with other DB employees and managers to synchronize implementation across the organization, ensure adherence to environmental protection regulations, and identify environmental risks.

GATHERING SPEED

Fortunately, as governments look to meet their net-zero goals, many are setting policies to encourage growth in rail transport. As part of its Green Deal, for example, the EU plans to invest €260 billion in all forms of rail transport. By offering a range of incentives, the EU hopes to grow the share of freight shipped via rail within its borders from 17% to 30% by 2030. In the US, the newly enacted Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act includes $102 billion for passenger and freight rail in the next five years (an increase of $87 billion from current funding levels) and an additional $106 billion for public transit alone.

China already boasts the world’s largest high-speed rail network and, under its National Rail Plan, hopes to double its footprint by 2035. To make its rail network truly sustainable, however, the country must substantially increase its use of renewable energy. Likewise, India plans to increase the share of freight shipped by rail from 27% to 45% by 2030 and to fully electrify its rail network using renewable sources of electricity.

In addition to these government efforts, proponents of rail transport can point to several underserved segments and geographies where rail has inherent advantages. If managed properly, they have considerable potential for attracting further financial and governmental support—and most important, more customers. They include:

- High-Speed Rail. Since 2004, the world’s high-speed rail network grew 350%. Most of that growth took place in China, and the results are impressive. The country now boasts two-thirds of the entire world’s high-speed network, and passenger activity there more than doubled between 2004 and 2016. Its success shows that high-speed rail can succeed in developed countries with large populations, especially when the distance between cities isn’t too long. Other recent projects include Morocco’s Tangier-to-Casablanca line (350 kilometers) and Saudi Arabia’s line connecting Medina with Mecca (450 kilometers), which officially opened in 2018. Additional projects are planned for India, the US, Canada, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia.

- Freight in Emerging Countries. Given the necessity of shipping heavy cargo across long distances, countries like Russia, Canada, Australia, and the US already have well-developed freight networks. Emerging countries with similar needs are likely candidates for further expansion, and several are already developing national plans to do so, including Brazil, Saudi Arabia, and Indonesia. India’s Dedicated Freight Corridor has already built 3,260 kilometers of additional lines over two primary corridors, with plans to more than double the length of new track in coming years.

- Urban Metro and Light Rail. While Europe, China, and Japan account for the great majority of urban and light-rail systems, there is considerable room for further growth in densely populated countries. Construction of urban rail networks has increased rapidly in recent years—primarily in Asia—with more on the way. The US has proposed $225 billion in new projects, while Australia is planning to invest $140 billion in systems in Sydney and Melbourne. An additional total of $140 billion has been earmarked for systems in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Ecuador, and South Africa.

ALL ABOARD

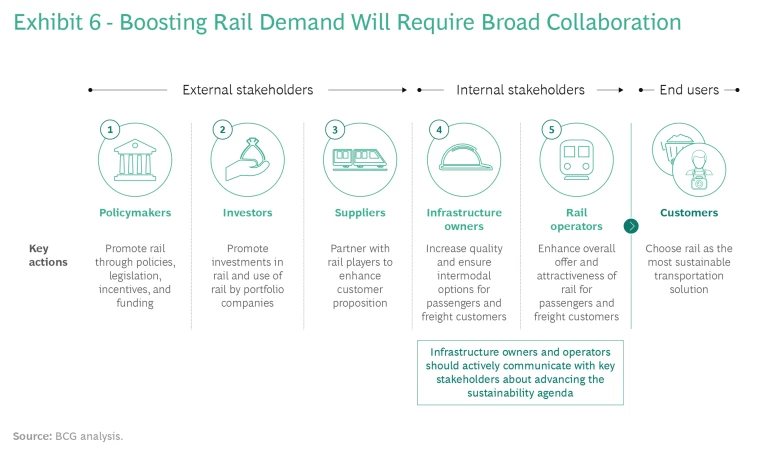

Ongoing efforts by the rail transport industry to boost its sustainability, efficiency, and flexibility have already begun to attract new customers—especially in freight but also in passenger rail. Yet to continue to build its customer base and contribute even more to the fight against global warming, the industry will need the support of five key stakeholders (see Exhibit 6):

Policymakers. Governments will be central in providing the policies, funding, and incentives needed to sustain the industry’s growth. Policies and plans at the national level are needed to promote rail not just as a more efficient and sustainable transport mode but also to meet national sustainability targets. Policies must include clear objectives for the rail sector and ensure a level economic playing field, given that rail uses less land, causes fewer accidents, and creates less noise pollution and congestion. Governments across the EU, for example, have reduced track-access fees to promote the use of rail for freight traffic while introducing additional usage fees and taxes on high-polluting industries, such as aviation and automotive. Direct governmental subsidies have helped support rail in many countries, including the US, China, and Saudi Arabia.

Adequate funding, however, is critical. Rail is a very capital-intensive business; in addition to subsidies, governments can implement funding mechanisms to provide the necessary capital for major rail projects. Public funds can be earmarked for specific brownfield and greenfield projects, and policymakers can help create the right incentives for increased private capital investment. For example, France’s “ecotax” on air travel—which adds between €1.5 and €18 to the price of every flight—is expected to raise more than €180 million annually, with the funds to be reinvested in ecofriendly transport, primarily rail. In the US, the Biden administration’s infrastructure bill sets aside $68 billion for passenger and freight rail upgrades. And, as mentioned, the EU’s Green Deal proposes investments intended to grow rail’s share of freight traffic to 30% by 2030.

Governments can also advance the rail agenda through direct legislation. They could, for example, encourage infrastructure owners to increase third-party access to their systems to incentivize competition. And legislators could enact laws cutting through the bureaucratic red tape that often slows new rail projects and policy changes, smoothing the licensing and approval processes, for instance. Brazil recently passed legislation designed to promote private investment and foster the development of infrastructure through the simplification of rail regulations and other measures. As a result, investments are expected to increase significantly.

Governments also have many ways to directly incentivize the growth and use of rail. Subsidies can be used to promote rail for operators, shippers, and passengers alike, increasing the transport mode’s economic competitiveness compared with other, less sustainable alternatives. Several countries in the EU have reduced rail freight’s track access fees to encourage companies to ship by rail rather than trucks. And Germany’s new government coalition has reduced the size of the trucks that must pay fees on their CO2 emissions from 7.5 metric tons to 3.5 metric tons.

To level the playing field further, governments could disincentivize higher-polluting modes of transport and the use of fossil fuels generally. The congestion charge imposed on drivers in London, for example, is designed to discourage car trips and raise funds to support public transportation. Countries are already enacting and enforcing laws intended to restrict the use of trucks, such as labor laws regulating working hours for drivers, limiting access of high-polluting trucks and cars to metropolitan areas, and taxing transport modes based on their sustainability.

Investors. By providing needed capital and encouraging the use of rail on the part of their portfolio companies, private investors can help promote its growth. Thanks to these investments, infrastructure owners could maintain, upgrade, and expand existing networks and build new stations. Operators could likewise maintain and upgrade, as well as acquire, new rolling stock and pursue technologies to increase sustainability and efficiency. And suppliers could invest in the development of digital solutions in the same spirit.

Some investors are purchasing rail operators outright. In 2019, Brookfield Infrastructure Partners, together with Singapore’s GIC, acquired Genesee & Wyoming, a freight-services provider in North America and Europe with over 21,000 km of owned and leased tracks. The $8.4 billion deal will enable Brookfield to further its net-zero infrastructure goals, in part by encouraging its other portfolio companies to ship goods over the company’s freight network.

Private investors are also coming to recognize the importance of having sustainable investment portfolios when managing risk and bolstering returns. Setting comprehensive emission targets for portfolio companies would encourage increased use of sustainable options, such as rail, throughout supply chains.

Suppliers. It is in the best interest of the industry’s suppliers to work with operators and infrastructure owners to enhance rail’s attractiveness to customers. Accordingly, they should collaborate to develop products for the industry that boost its sustainability, lower costs for customers, and improve the rider experience.

Alstom, for example, is working with Dutch infrastructure owner ProRail to develop automatic shunting locomotives to demonstrate the viability of fully automated trains. Siemens and Deutsche Bahn are testing the use of hydrogen to power trains on nonelectrified lines. Deutsche Bahn is also heading up a consortium of freight operators, OEMs, and leading engineering providers to develop and test digital automatic coupling. By automating the coupling process, this technology will allow trains to be put together faster and more flexibly, reducing risk for workers, and increasing rail’s competitive position and market share across Europe.

Infrastructure Owners. Establishing new rail networks and increasing the utilization of current networks are critical actions for expanding rail’s share of transport. Shippers and passengers must have the flexibility to move goods or travel where and how they want to. This will require developing new infrastructure projects—and not just new lines on denser networks. New stations, terminals, maneuvering yards, catenary power systems, and renewable energy sources will also be needed.

At the same time, owners must increase the utilization, efficiency, and overall performance of their existing infrastructure. Networks must be properly maintained and upgraded regularly to ensure safety; to boost sustainability, efficiency, and speed; and to promote passenger convenience and comfort. To that end, owners must incorporate new technologies to enhance the efficient use of their infrastructure.

One way to boost network demand is to increase the availability of multimodal transport options, especially now that passenger and freight clients are taking an end-to-end view of the customer journey and freight logistics. OBB, Austria’s national railway, offers charging points for electric vehicles at train stations and has even developed its own electric-car-sharing fleet. Added bicycle parking and special railcars help ease the journeys of bicyclists. Freight infrastructure, too, can take advantage of added intermodal options. In support of the country’s sustainability goals, Belgium’s Infrabel, for example, has committed to increasing the proportion of freight moved via rail by improving intermodal connections at the port of Zeebrugge.

Infrastructure owners will also need to engage with policymakers, investors, suppliers, operators, and customers to ensure the success of these projects. Regular and open communication will help attract shippers and passengers, creating the customer demand needed to generate the expected returns.

Operators. Rail operators, too, must invest in enhancing the sustainability, utilization, efficiency, and overall attractiveness of their operations. To gain share from other transport modes, operators need to keep up with the maintenance and modernization of their rolling stock and take a more customer-centric approach throughout their activities.

Operators should completely rethink the entire customer journey to remove pain points in places that matter most to clients. Optimizing timetabling and dispatching will enhance the timeliness of operations, as will providing a superior interface for passengers and shippers and improving end-to-end connectivity with other transport modes. New technologies, such as mobile apps, can ease the ticketing and payment process and should be promoted to all customers through new marketing, sales, and pricing efforts. Further, operators can update stations and terminals with cafes, retail shops, working desks, and other amenities. And as the world emerges from the COVID pandemic, establishing health, safety, and cleanliness protocols will be key to attracting passengers back to rail.

As with infrastructure owners, active communication with key stakeholders regarding goals and successes will help operators optimize their systems and lift customer demand.

DRIVING WHEELS

Evidence of the increased attractiveness of rail can be found worldwide. Shippers, in particular, are taking advantage of rail’s sustainability and flexibility with impressive results. For example, as part of its effort to reduce its carbon footprint, UK grocer Tesco is shipping a significant proportion of fresh produce it sources from Spain by rail, a move that is expected to take 65,000 trucks off the road and reduce GHG emissions by 4,500 tons.

In a similar move, Swedish grocer Coop has contracted with a major European logistics firm to increase its use of rail (for shipping groceries to its outlets) from 10 to 20 trains per week, which will remove an estimated 520 trucks weekly from the country’s highways.

Operators and infrastructure owners looking to grow their customer base by becoming more sustainable would be wise to carry out the following four concrete steps:

- Understand the potential impact of climate policies on your business and assess the current state of your company’s emissions. Determining the emissions baseline, reviewing ongoing emissions reduction initiatives, and benchmarking peers will enable you to understand and manage the risks and challenges in carrying out climate plans for your current business model.

- Define your sustainability ambitions and strategy and lay out plans to deliver the desired future state. This step should include defining the sustainability value proposition for customers and developing new value-added products and services. Specific actions should include determining the impact and cost of particular initiatives and running scenarios to identify the most cost-effective options for reaching climate targets.

- Begin the journey by defining a concrete roadmap and preparing the organization for change. The roadmap should outline the organizational structure and processes needed to reach targets and include lighthouse projects and quick wins that can smooth the transition. Begin from the top down to revamp your company’s people and culture for a low-carbon world, and revise processes to foster cultural change.

- Engage the full ecosystem by partnering with suppliers and subcontractors across the value chain to explore and develop low-emissions technologies and practices. Collaborate with ecosystem stakeholders to promote a climate-friendly industry.

ALL SIGNALS ARE GREEN

Rail transport is essential for meeting global climate targets. Indeed, our net-zero goals will be far harder to attain unless we can increase rail’s use and sustainability. Despite having huge advantages in efficiency and sustainability, however, rail operators are finding it challenging to grow their customer base of passengers and freight. Cars and trucks continue to attract travelers and shippers, largely because of pricing, flexibility, and perceived security concerns.

Reversing this trend will take a concerted effort on the part of all major stakeholders. But rail operators have an inherent advantage—rail is already far more climate friendly than other transport modes. By continuing to increase its sustainability efforts, the industry will attract more customers looking to reduce their carbon footprints and lower their costs.

The more sustainable rail becomes, the more customers it will attract. And more customers mean more resources for improving sustainability. The task ahead for the industry is to complete and widen this virtuous circle.