From 2015 to 2020, global liquified natural gas (LNG) volumes increased ~50% as cargos fed skyrocketing demand in Asia. This opportunity was largely captured by American and, to a lesser extent, Australian energy producers. Canada was conspicuously absent, but it didn’t have to be this way.

In 2010, Canadian and US energy producers had proposed similar levels of LNG export development, ~15 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d). In the years since, the US has largely fulfilled its promise by building 7 facilities with a total capacity of >12bcf/d, while Canada plays catchup with just one facility of ~2bcf/d under construction.

One has to ask – is the same script playing out with hydrogen?

Hydrogen has long been touted as a climate panacea. While we recognize the broad applicability of green hydrogen (made from renewable energy) and blue hydrogen (made from natural gas with carbon capture) across abatement applications, we are also keenly aware of its drawbacks. These include transport constraints (which necessitate hydrogen’s conversion to ammonia and methanol for overseas export) and end-to-end energy inefficiency. These hurdles will likely concentrate hydrogen’s future role in applications where it serves as a process feedstock, and in resource-poor geographies short on quality renewable resources and sequestration opportunities. Enter Northeast Asia.

By 2030, Japan and South Korea are forecast to import 3 million tonnes of low-carbon hydrogen annually. Capturing even one-tenth of that opportunity (the amount produced by a typical hydrogen facility) would generate approximately $1 billion in annual export revenues along with thousands of jobs. By 2050, Japan and South Korea are expected to import between 15 and 50 million tonnes annually, turning that one-tenth opportunity into a powerful annuity for major exporting countries.

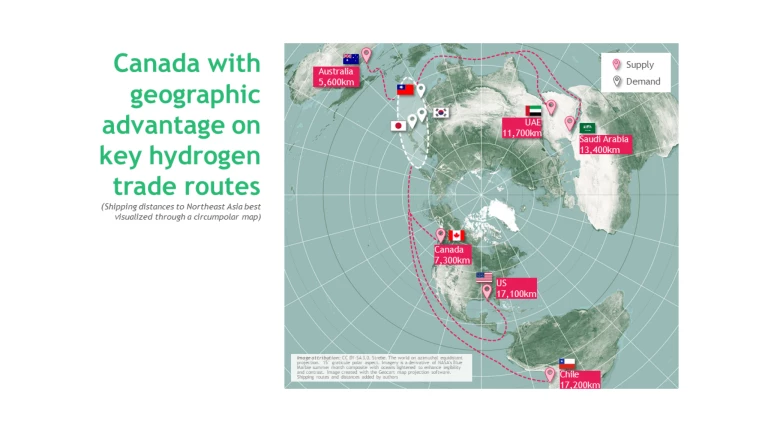

One of Canada’s opportunities is to supply these Asian markets with blue hydrogen. British Columbia and Alberta have plentiful low-cost natural gas resources (more than 200 years worth at current production), ample geologic storage for carbon dioxide near industrial hubs, and globally leading carbon capture technical knowhow. Another asset is Canada’s proximity to major importers – from its West Coast, Canada can ship hydrogen to Northeast Asia at half the cost of American and Middle Eastern competitors. And at a time of increasing focus on energy security, Canada is a trusted supplier whose products avoid potential chokepoints such as the Panama Canal, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Strait of Malacca.

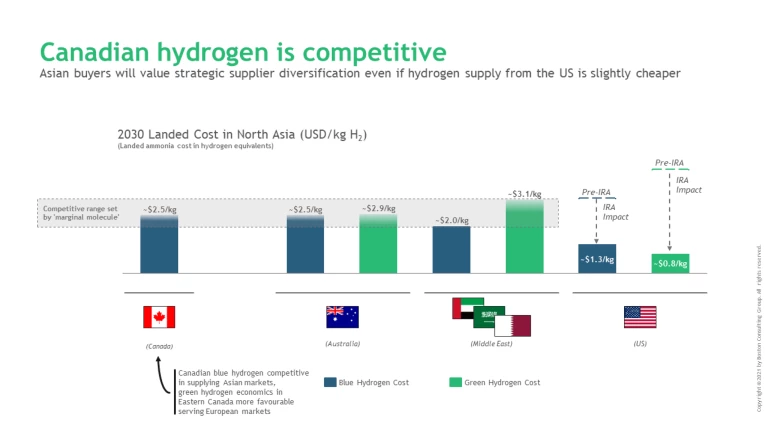

But Canada is at risk of missing the moment. International competitors (including the US and Australia, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates) are moving quickly and in a more coordinated manner. The US will be a particularly fierce rival. Fanned by generous production tax credits from the Inflation Reduction Act, US exporters will be the lowest cost supplier.

This does not mean, however, that there is no room for Canadian hydrogen---Asian importers value supplier diversity too much. The liquified natural gas (LNG) market is an informative case study, wherein Japan deliberately imports from nine different countries to increase energy security. Hydrogen will be no different. Japan & South Korea will choose to import from countries other than the US, including jurisdictions which Canada is cost competitive with.

But Canada could miss the multi-billion dollar hydrogen opportunity if it does not begin taking decisive action now. Australia serves as a template for galvanizing action in hydrogen that Canada can emulate. As a secure supplier with advantaged transport and a strong natural resource base, Australia’s hydrogen positioning is similar to Canada’s. But unlike Canada, Australia has attracted 80 announced hydrogen projects, 15 of which have received final investment decisions. Canada, by contrast, can point to five announcements, only one of which has been approved.

Australia’s traction is the result of a concerted push across government and industry. In 2019, the government published and promoted a national hydrogen strategy, which drove commercial activity by implementing consistent and light-touch regulation and shaping international markets. Australian state and federal governments worked together to streamline and eliminate redundancy in permitting processes, identify “hubs” that would qualify for support and sign international partnerships with key markets, including Japan and South Korea. Industry also worked collaboratively, convening a roundtable to inform policy.

It is not too late for Canada to follow the Australian model. Now is the time for Canada to harmonize federal and provincial strategies and create a united front in which industry and government work toward common goals, including reaching out proactively to Japanese and Korean markets.

The global hydrogen market is forecast to grow for 30+ years, but Canada must move quickly to lead in this world class opportunity.