For decades, companies and investors have grown accustomed to deepening globalization, where countries facilitate trade and investment, exercise restraint in imposing market barriers, and cooperate through international rules and institutions. In this version of the world, geopolitical risks exist only on the margins of global business.

That picture is changing rapidly. Trade protectionism and industrial policy have resurged, leading to a rise in tariffs and subsidies. Governments are expanding regulations to combat climate change and exercise more control over the digital economy. Supply chains are being disrupted by sanctions and export controls, as well as by armed conflict in different regions of the world. All the while, multilateral institutions are ceding ground to less institutionalized, multipolar interactions among countries.

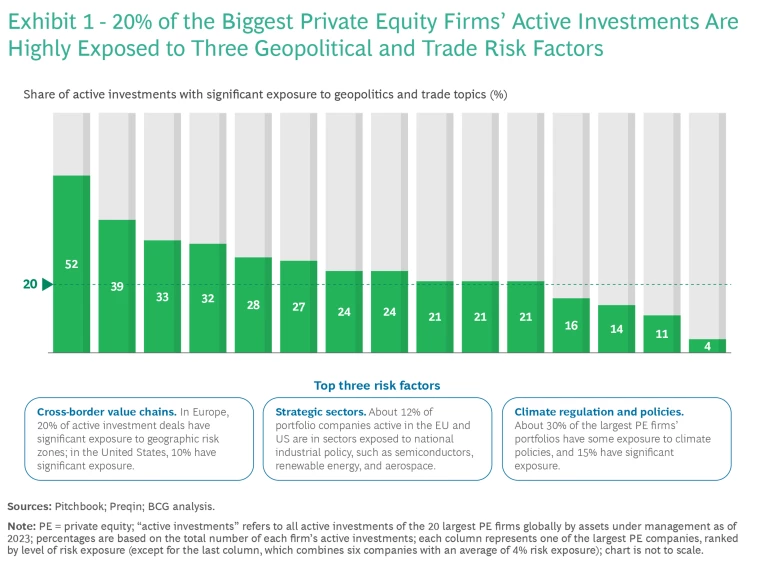

As investors with a global, cross-sectoral footprint, private equity (PE) firms will see significant impact—with risks and opportunities—from this new normal in geopolitics and trade. BCG analysis has found that among the 20 largest PE fund portfolios, an average of 20% of assets are exposed to geopolitical and trade risk in three main areas: cross-border value chains, strategic sectors, and climate regulation and policies. For several funds, the percentage exposed to risk is much higher. (See Exhibit 1.)

PE firms develop allocation, deal due diligence, and divestment and exit strategies across diverse portfolios. In each part of a portfolio, they have the potential to make more effective decisions and deliver stronger returns by accounting for geopolitical and trade dynamics. Compared with companies in other sectors, such as energy and mining, most PE firms have yet to build significant “geopolitical muscle.”

The Three Areas of Geopolitics and Trade Risk

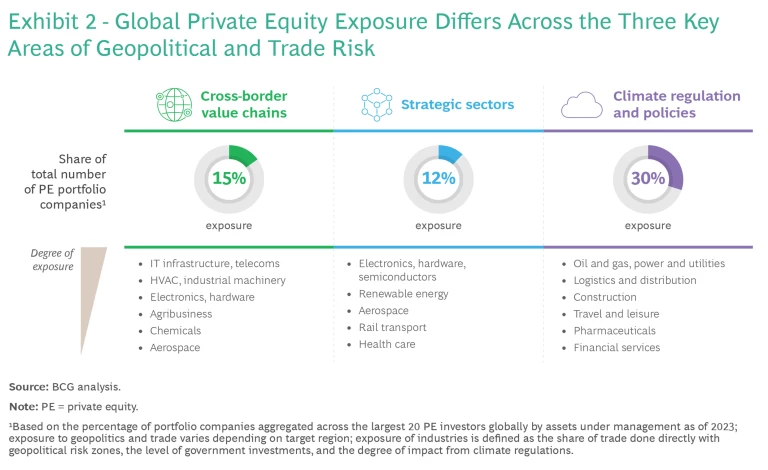

The three areas of geopolitical and trade risk are shaping international business dynamics in important ways, across several major industries. (See Exhibit 2.)

Cross-border value chains. A series of events, ranging from the COVID-19 pandemic to trade barriers and sanctions related to armed conflicts, has disrupted global trade in recent years. To improve resilience, governments and companies are working to restructure supply chains (through dual sourcing and near shoring, for example). The flow of goods, services, and capital is also being shaped by geopolitical alignments among countries, reflecting a more multipolar world. For PE firms, these changes demand sharper analysis of their portfolio companies’ supply chain and end-market exposure across geographies.

Strategic sectors. Governments are expanding the definition of strategic sectors beyond traditional areas like defense to include fields such as clean energy, semiconductors, and biotech. Examples include the US’s Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan—both of which emphasize green technologies—as well as the US’s CHIPS and Science Act and the European Chips Act. These measures not only inject significant amounts of government funding into strategic sectors but also attract private investment.

Climate regulation and policies. Governments are pledging carbon neutrality to mitigate the impact of climate change, with ambitious net zero and green energy targets and new regulations. For example, governmental carbon pricing instruments now cover 23% of global greenhouse gases. The EU has introduced a carbon border adjustment mechanism to complement its existing cap and trade system, which may inspire other major economies to join a “carbon club.” The US’s Inflation Reduction Act, in turn, provides a variety of tax credits and other incentives to stimulate domestic production of advanced batteries, green hydrogen, and other low-carbon products and energy sources.

Three Key Sectors Disrupted by Geopolitics and Trade

For PE firms, geopolitical and trade dynamics are most impactful in three sectors: industrial goods, tech, and energy.

Industrial goods, such as machinery and automotive products, rely on complex physical supply chains, access to raw materials, and the ability to export physical items to end markets. Geopolitical and trade dynamics are constraining access to both import and export markets, as governments restrict exports of critical technologies or materials, raise tariffs, or incentivize domestic manufacturing, for example. These dynamics can increase both the cost of doing business and the risk of sudden policy shifts that disrupt cross-border supply chains.

Tech, including semiconductors, electronics, the Internet of Things (IoT), and artificial intelligence, is at the forefront of the twenty-first-century economy. Governments are stepping up efforts to influence where these technologies are developed and produced and how they are used, to address national security and other concerns. The US, for example, is restricting the export of sensitive semiconductor technology to certain trading partners, while also incentivizing advanced chip fabrication and R&D in the US through the CHIPS and Science Act. As companies migrate into IoT, AI, and cloud-based infrastructure, they become increasingly susceptible to restrictions on cross-border data flows.

Energy, including hydrocarbons and renewable energy, faces particularly complex dynamics. Geopolitical conflicts are disrupting global oil and gas markets, boosting the profitability of some producers while raising costs for consumers. In parallel, governments are working to price carbon and accelerate the transition to green technologies and energy sources.

Several Possible Global Scenarios

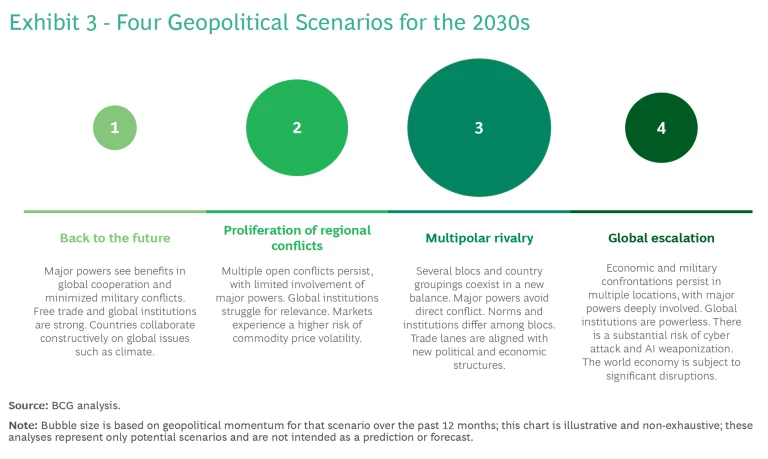

BCG sees four hypothetical but plausible scenarios of differing severity for how the geopolitical landscape could look in the 2030s. These range from a return to cross-border cooperation and emphasis on free trade to global escalation characterized by discord, including potential economic and military confrontations. (See Exhibit 3.)

Recent events suggest that the march toward more multipolar competition is accelerating. In this potential environment, western and eastern economic blocs find a new balance, with more protectionist governments and multipolar geopolitics. Companies could expect a shift to more regional supply chain clusters with fewer global interdependencies.

How PE Investors Can Prepare

PE firms that strengthen geopolitical decision making stand to better protect themselves against downside risks while also identifying ways to become more competitive. There are three main actions PE firms should consider:

- Review the overall fund strategy. Firms should assess their overall portfolio for geopolitical and trade risk exposure and identify the companies that require attention. This should entail screening for industries that are especially at risk and evaluating potential changes in geopolitics, trade, and regulations, as well as doing some competitive benchmarking to identify challenges and opportunities.

- Identify opportunities to create new portfolio value. During their assessment of which companies within their portfolio may be at high risk, PE firms should estimate the scope of the impact by analyzing revenue and cost drivers, the value chain, geographic factors, and sector exposure. This should help them identify which value creation levers to act on.

- Incorporate a strong geopolitical perspective during the due diligence process. PE companies should actively apply geopolitical perspectives during the due diligence process with acquisition targets—especially for the most at-risk transactions—to assess target attractiveness and market outlook.

As global trade and other disruptions persist, PE investors can expect geopolitical risk assessment to become an increasingly important part of strategic investment decisions. Now more than ever, fund managers need to assess investment portfolios for exposure to unexpected events and evolving policies. Companies within the PE portfolio can also improve competitiveness by understanding and anticipating these trends. Making sense of these risks and trends will help PE companies effectively make the most of emerging opportunities.

The authors wish to thank Eric Justin for his contributions to this article.