Since the turn of the century, global health has stood as one of humanity’s greatest collaborative achievements. Donor nations, multilateral organizations, recipient countries, and communities have worked together to tackle some of the world’s most pressing health crises. From child immunization to the decline in HIV deaths, the world showed its ability to unite around shared health challenges. But now, the global health financing landscape stands at a critical juncture, demanding a profound rethinking of how health initiatives are structured, administered, and funded.

For decades, global health initiatives operated on a simple premise: wealthy nations funded global health organizations to address health inequities through grants and technical aid. Of the official international flows for health, 61% are official development assistance (ODA) grants, 17% are ODA loans, and 22% are other official flows. This system facilitated groundbreaking achievements, such as combating pandemics.

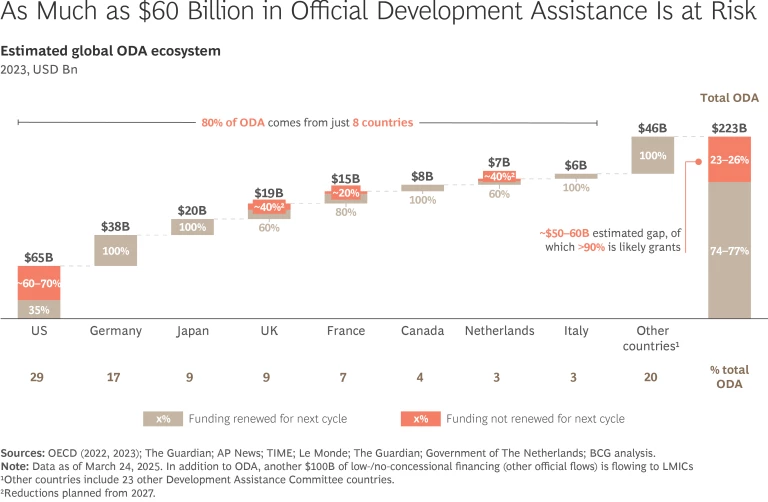

Globally, as much as $60 billion in ODA is at risk. (See exhibit.) In early 2025, the UK cut $8 billion in foreign aid, France slashed $2.68 billion, and the United States cancelled $54 billion in multi-year US Agency for International Development contracts and another $4.4 billion in US State Department initiatives. These cuts are not just cyclical belt-tightening but reflect the political pressure Western governments face to boost military spending and reduce their chronic budget deficits.

The shortfall left by donor cutbacks is significant—around 25% of current global health aid. And that’s before factoring in the growing needs for health services due to the rise in noncommunicable diseases, chronic conditions, and aging populations. Closing this gap will require a diversified financial strategy. Along with increased domestic financing by recipient countries, it will be crucial to mobilize private-sector capital through innovative mechanisms like blended finance, which use philanthropic or public funds to de-risk and attract commercial investment. This must be complemented by new contributions from nations that have historically played modest roles in health funding. For example, the expanding BRICS+ alliance is seen by many as a group of countries that, individually, could play critical roles in filling at least part of the funding gap. Together, the BRICS+ countries represent 27% of global GDP and are projected to surpass the G7 by 2050.

But as Western nations step back and governments in countries like China, India, and other emerging powers hopefully step forward, the global health community must adapt to a new reality. Trust in science and intergovernmental agencies is eroding, undermining the framework that supported decades of progress. In the near future, investments could be evaluated not just for their health impact, but for their economic and strategic value to the new donor nations.

This transformation entails more than institutional restructuring. It requires a paradigm shift in how health care is provided in low- and middle-income countries. Rather than framing initiatives as charitable endeavors, the global health community must recast their efforts as strategic investments that deliver measurable returns. The emerging funding landscape, dominated by BRICS+ nations and private investors, prioritizes bilateral partnerships, infrastructure development, and economic outcomes.

The New Funding Order

The new funders entering this space—particularly the BRICS+ countries (founders Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, plus newcomers Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates)—bring different expectations. As these funders take a more prominent role in global health financing, we can expect three major shifts, as summarized below. Each of these changes will have significant implications for how, where, and why health investments are made in the coming years.

Changes in funding channels and priorities

The new funders’ investments will be more bilateral and targeted, with more loans instead of grants, and infrastructure financing rather than donations of medical supplies. And given that the emerging countries are less willing to absorb losses, financing may be structured with different tranches of risk and return. Grants could be earmarked for vital, but high risk, services—and loans could be made to health investments that can generate a return for both emerging-country and private investors.

And rather than channeling aid through global health agencies, these new funders typically deliver aid through their own platforms—either via national development agencies or other government-to-government arrangements. For example, China channels roughly 95% of its contributions to other countries as “other official flows,” which fall outside traditional official development assistance criteria given their limited concessions.

However, health is a notable exception. In 2021, 92% of China’s international health investments qualified as ODA, reflecting a more concessional approach in this sector. This pattern, consistent since the launch of the country’s broader Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, symbolizes the different priorities and mechanisms of emerging economies compared to traditional donors.

Geographic reorientation of investment

Investment flows are likely to shift toward regions and countries that align with the economic and strategic interests of these funders, such as Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Latin America. In contrast, Sub-Saharan Africa, historically a major focus of traditional health aid, has received a relatively small share of BRICS+ investments to date. Going forward, new global health funders are expected to prioritize countries for assistance based on how it may support the funding country’s economic goals, rather than solely on humanitarian need. Initiatives like China’s Health Silk Road and India’s vaccine diplomacy symbolize this strategic approach, where health investments serve broader economic and geopolitical objectives.

Transformation in project types

The types of projects receiving funding are also likely to change. If new funder nations step forward, recipient countries could see a shift toward infrastructure-heavy investments, which could mean increased support for hospital construction, pharmaceutical manufacturing hubs, surveillance networks, digital health platforms, and cold-chain logistics hubs.

This shift, if realized, could leave critical aspects of health funding underserved. Areas such as primary health care, maternal and child health, infectious disease prevention, services targeting hard-to-reach populations, and community-based services—all proven to be cost-effective for health outcomes—could be overlooked in this new paradigm.

Adapting to the New Realities

Global health institutions do more than just channel funds; they also play a critical role in providing technical assistance and promoting innovation. To thrive in the new order, these organizations must undergo a fundamental transformation.

First, they must achieve greater operational efficiencies and learn how to do more with less. That means consolidating overlapping mandates, streamlining internal processes, and improving coordination among organizations. The World Health Organization’s refocus on core functions, coupled with efforts by Gavi and the Global Fund to break down silos, show that global health must move beyond vertical programs to prioritize investments that build more resilient and efficient approaches.

Second, the sector must embrace the growing role of regional and local players like ASEAN Health and Africa CDC, and global health institutions must build in more effective partnerships with them. With strong political backing, cultural awareness, and extensive local knowledge, these organizations are uniquely positioned to address regional health challenges. Unlike traditional funding models—where grants are funneled through intergovernmental agencies—these regional groups increasingly receive direct funding and technical assistance from a diverse group of emerging donors. This funding often comes with fewer strings attached, enabling these regional bodies to build essential operational capacity and tailor their efforts to local needs. As a result, they are playing a greater role in coordinating and delivering public health services, and future operating models need to factor in their growing contributions.

Third, and most critically, global health must innovate its capital stack by restructuring funding opportunities to appeal to a broader pool of investors. This means moving beyond traditional grant models to develop blended finance mechanisms, public-private partnerships, and outcome-based financing. In the future, large multilateral funds could work with specialized financial intermediaries, development finance institutions, and investment banks that have expertise in structuring complex financial products. These partners can help design the different tranches for specific countries, projects, or risk profiles. This would help investors align contributions with their priorities, while attracting private investors who have rarely, if ever, financed global health initiatives before. Innovating the capital stack also means diversifying the channels for investment, helping to increase direct financial flows to each country alongside, not just through, existing multilateral mechanisms.

Future models must also create stronger incentives for recipient nations to finance part of their health needs. Governments can implement innovative fiscal policies, such as earmarking a portion of value-added taxes (or “sin taxes” on tobacco and alcohol) for health, a strategy that has proven effective in countries like the Philippines. In addition, public-private partnership can be used to co-finance health initiatives, ensuring that domestic contributions are complemented by private capital. Ultimately, achieving sustainable health systems will require targeted financial and technical support to create these mechanisms, improve efficiency, and prioritize sustainable health investments.

Health as a Measure of Global Collaboration

Global health has historically been a leading example of successful multilateralism, demonstrating the benefits of international cooperation. It remains one of the most visible, immediate, and universally relevant fields of collaboration. The current transformation of the global health system is more than a policy shift; it is a barometer of broader trends in international cooperation.

The global community’s response to this pivotal moment is critical, for the stakes go beyond health systems. As global health adapts and continues to deliver, it may offer a blueprint for a future where cooperation still holds—even in a fractured world.