The projected economic losses from increasing extreme weather are substantial. In the most affected regions, climate change could cause economic loss of up to 19% of GDP by 2050. In response, adaptation and resilience efforts are climbing higher on global agendas. The critical next step is turning strategic intent into well-funded, prioritized, and actionable projects.

In many countries, the estimated investment needs are multiple times more than public sector budgets and financing capacity. All forms of capital from public, private, multi-lateral development to philanthropic sources will need to be deployed in adaptation.

For private sector companies, the case for investing in adaptation and resilience to protect their own businesses is compelling: some self-report benefit-to-cost ratios as high as 35:1.

Mobilizing capital at scale is achievable—but it demands clear quantification and valuing of benefits, well-orchestrated public-private collaboration, and investment-ready projects. At the same time, rigorous mitigation remains essential as many resilience solutions risk becoming ineffective or unfeasible if temperatures rise beyond 1.5–2°C.

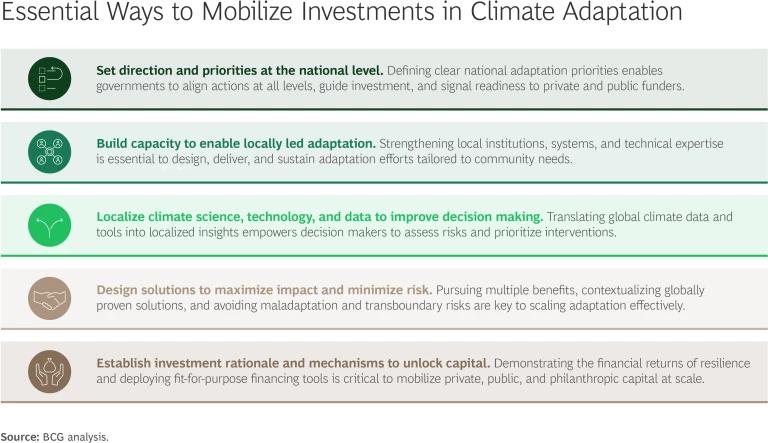

Collectively, the five imperatives discussed in this article can create the enabling environment needed to attract investment, scale adaptation solutions, and drive lasting change. (See the exhibit.)

#1: Set Direction and Priorities at the National Level

Governments may consider developing and implementing National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), under the UN framework, as living strategies that define national priorities, guide investment, and coordinate adaptation across sectors and levels of government. So far, more than 70 countries have submitted their NAPs.

NAPs can help align ministries and embed resilience into policy and planning. For funders, they often signal readiness through prioritized, credible, and investment-aligned roadmaps. For the private sector, NAPs can serve to provide clear direction for innovation and business development.

Critically, NAPs can help governments prioritize and sequence actions, ensuring that limited resources are allocated efficiently to areas with the highest cost of inaction—whether they face the greatest risks or offer the greatest opportunities. Such prioritization helps bridge the gap between high-level ambition and on-the-ground delivery.

In countries with strong NAPs—such as Germany, Ethiopia, and the Philippines—these plans are already advancing the alignment of national, provincial, and sectoral adaptation strategies and prioritizing actions in climate-vulnerable industries.

#2: Build Capacity to Enable Locally Led Adaptation

Effective adaptation requires local capabilities across the entire cycle from strategy to delivery. Even the best-designed NAPs rely on local institutions’ abilities to shape, implement, and sustain actions that reflect community realities. Yet many countries still face gaps in technical expertise, systems, and authority. Investing in technical expertise, institutional readiness, and coordination systems at the local level is often as critical as financing itself, especially in vulnerable communities.

Nepal’s Local Adaptation Plans of Action (LAPA) demonstrate how bottom-up, inclusive capacity building enables community-led adaptation that is integrated into local planning. By training municipalities and communities to assess vulnerabilities, set priorities, and integrate them into local plans, LAPA built lasting institutional capability for communities to design and sustain adaptation measures.

#3: Localize Climate Science, Technology, and Data to Improve Decision Making

Localized climate insights are the foundation for turning national priorities into practical plans. Global datasets and models are essential, but they need to be adapted to reflect the geography, vulnerabilities, and socioeconomic conditions of specific regions and communities. Without this localization, it is difficult to assess climate risks with precision, prioritize interventions, or design solutions that are both effective and investable.

In Lagos, Nigeria, the government downscaled global climate models to assess climate risks at a high degree of granularity. Integrating these models with socioeconomic data allows decision makers to identify local hotspots, prioritize adaptation investments, and present funders with a data-driven project pipeline.

Localization requires high-quality, accessible data. Risk assessments, modeling, investment planning, and early-warning systems all depend on real-time climate, hazard, and vulnerability data. Yet in many regions, critical data remains outdated or unavailable, leaving decision makers without the tools to act effectively or attract investment. Emerging open-source data platforms are helping close this gap by making high-resolution climate, hazard, and vulnerability data more widely available.

#4: Design Solutions to Maximize Impact and Minimize Risk

Addressing climate adaptation challenges demands integrated solutions, localization of proven solutions, and proactive management of risks.

Adopt multibenefit solutions. Adaptation solutions can achieve greater impact when designed to achieve multiple benefits—including combining resilience with mitigation, social and economic development. These multibenefit approaches are gaining momentum: financing for combined mitigation and adaptation projects tripled between 2018 and 2023, to nearly match standalone adaptation funding, according to Climate Policy Initiative (CPI).

Such solutions are often more cost-effective, fundable, and durable. They help break down sectoral silos and support systems-level outcomes across climate, economy, and nature. Many resilience interventions inherently contribute to mitigation goals and related benefits. For example, investments in grid resilience not only help manage increased loads during heat waves but also enable higher integration of renewable energy. Nature-based and urban infrastructure solutions—such as mangrove restoration, regenerative agriculture, agroforestry, green roofs, and permeable pavements—also offer powerful benefits for mitigation and ecosystem health.

Examples around the world illustrate this approach in action. Two cities in Indonesia are demonstrating this in practice. The Building with Nature project in Demak, Central Java, designed an integrated approach to build resilience against sea level rise and coastal erosion via semipermeable brushwood structures and mangrove restoration, and by training farmers in sustainable mangrove aquaculture. Jakarta’s Coastal Defense Strategy also integrates seawalls and drainage upgrades with groundwater management measures, soon-to-be complemented with mangrove restoration. In Kenya, solar-powered irrigation systems bolster agricultural resilience and provide surplus electricity to the national grid.

Balance localization and replication of global solutions. Effective adaptation means responding to specific local climate risks, ecosystems, and social contexts. Yet designing effective solutions does not always require starting from scratch. Many adaptation interventions—such as urban heat action plans, early warning systems, flood defenses, and nature-based buffers—are already proven and available. Success requires finding the right balance between replicating what works and tailoring it to local contexts.

For example, Vietnam’s mangrove restoration, Ahmedabad, India’s heat action plan, and the Netherlands’ wetland-based flood management program provide clear templates for similar contexts. Recent Temasek and BCG research underscores the potential to transfer flood protection technologies from developed to emerging markets by reducing costs and adapting delivery models. Leveraging proven models with appropriate adjustments can save time, cost, and effort.

Manage maladaptation and transboundary risks. As solutions are scaled and adapted, care must be taken to avoid doing harm, both within and across borders. Poorly designed interventions may increase vulnerability instead of reducing it—a phenomenon known as maladaptation. For instance, coastal barriers can redirect flooding risks, and agricultural technologies introduced without suitable infrastructure can reduce resilience.

Engaging local institutions and communities is critical to sustainable adaptation. In China, Sanya’s Sponge City wetlands project exemplifies the value of context-appropriate infrastructure, coordinated institutional roles, and community-integrated design.

Additionally, transboundary climate risks affect shared ecosystems, supply chains, financial flows, trade links, and migration—and they are growing in complexity. For example, the 2011 Bangkok floods disrupted global automotive supply chains. The impacts of upstream decisions along shared river basins, like Southeast Asia’s Mekong River, demonstrate the necessity of coordinated multicountry action.

Although many regions have developed robust strategies, coordinated cross-border implementation remains challenging. One successful model is the long-term collaboration among 14 countries sharing Europe’s Danube River basin—enabling joint risk assessments, shared governance, and integrated investment planning.

Transboundary impacts increasingly trigger cross-border migration. As highlighted in BCG’s recent research with the University of Cambridge, growing water stress is causing cross-border displacement in Southeast Asia, thereby intensifying pressure on labor markets, humanitarian systems, and regional stability. Proactive coordination is crucial to mitigating these broader developmental and security challenges.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on climate change and sustainability

#5: Establish Investment Rationale and Mechanisms to Unlock Capital

Attracting significant capital for adaptation requires a strong investment rationale and mechanisms that translate climate resilience into financial returns.

Clarify the business case and monetization pathways. Adaptation delivers measurable value through tangible benefits. For governments, these benefits include avoidance of GDP losses, improved public health, more secure livelihoods, and enhanced ecosystem resilience. For businesses, adaptation safeguards assets, stabilizes supply chains, and protects workforce health while unlocking commercial opportunities in climate-smart infrastructure, resilient agriculture, and water services.

Yet the investment gap is stark. According to CPI, developing countries’ annual adaptation costs could exceed $380 billion by 2030, yet only $65 billion was mobilized in 2023—more than 90% of it from public sources.

Private and philanthropic capital remain largely untapped. A major barrier is the difficulty of directly linking resilience benefits to financial returns. Because these outcomes—many of which are tied to avoiding the cost of inaction or generating broader societal benefits—are challenging to quantify and monetize, the enabling investments are less attractive to private capital providers.

However, the monetization mechanisms outlined below are showing how resilience can make adaptation investable.

- User-paid revenue models, where end users pay directly for services such as irrigation or energy. For instance, solar-powered irrigation systems can be deployed on a pay-as-you-go basis, while also feeding surplus electricity into the grid to generate additional income.

- Contractually guaranteed cash flows, where investors are repaid through long-term agreements with governments or utilities. An example is the use of availability-based payment models for flood diversion tunnels or dike reinforcements, as seen in the Netherlands and the US.

- Asset value capture, where adaptation measures increase the value of nearby land or infrastructure. Coastal protection projects, for example, can raise urban land values and attract private development. Such models have been explored or applied in Singapore, Jakarta, and the Netherlands.

- Environmental credit and by-products markets, where nature-based solutions produce tradable credits or marketable byproducts. For instance, mangrove restoration projects can generate blue carbon credits, while seaweed farming offers both environmental benefits and commercial outputs.

- Cost avoidance and efficiency gains, where adaptation reduces long-term operational costs or damage. Watershed management is one such approach—it can lower downstream water treatment costs by minimizing runoff and sedimentation, generating savings for utilities.

Leverage diverse forms of capital and financing instruments. Mobilizing finance at scale requires blending multiple forms of capital—public, private, and philanthropic—with varying risk-return expectations.

To bridge risk-return gaps and unlock private investment, a wider range of financial instruments can be valuable. These include guarantees (such as for offtake) that de-risk early-stage or lower-return projects while preserving upside for commercial investors.

At the same time, many adaptation projects are not yet investment-ready. They often lack the technical detail, financial modeling, or structuring needed to access available finance. As a result, capital providers struggle to assess where and how to invest. To address this, new platforms and vehicles—some launched, others under development—seek to:

- Build robust project pipelines, with credible risk-return profiles and implementation plans.

- Match capital to project scale, risk-return profile, and broader public benefits.

- Coordinate across agencies and investors, bundling interventions by geography, theme, or delivery model.

Examples include country platforms that align planning, funding, and capacity. Additionally, blended finance vehicles, such as the Lightsmith Climate Resilience private equity fund, channel capital into companies providing resilience-enabling technologies—including climate analytics, risk modeling, and water systems—across emerging markets.

Make insurance fit-for-purpose. Insurance can play a dual role: providing support after disasters and proactively enabling climate resilience and investment quality.

- Post-Disaster Safety Net. Insurance can provide rapid, rules-based payouts to support response, recovery and rebuilding with longer term resilience in mind. Parametric insurance is particularly effective in this role, with payouts triggered by predefined climate thresholds. Programs such as the InsuResilience Global Partnership and the African Risk Capacity have helped expand access across vulnerable countries. In India, the Self Employed Women’s Association has piloted a parametric heat insurance product for informal women workers, offering timely compensation during extreme heat events. Catastrophe bonds have also helped governments mobilize disaster response funding quickly: for instance, the Philippines received a $52.5 million payout under a World Bank–issued sovereign catastrophe bond following a typhoon in December 2021.

- Proactive Enabler of Resilience. Insurance instruments can help price climate risk, reduce capital costs, and increase the bankability of adaptation investments. Credit enhancements can align financing terms with resilience KPIs—such as expanding coverage or narrowing protection gaps—embedding adaptation incentives directly into financial structures. Some insurance tools are beginning to incorporate these incentives into traditional structures. For example, the North Carolina Insurance Underwriting Association issued a $600 million catastrophe bond that includes a resilience feature: each year, a slight additional spread is paid into a dedicated resilience fund, reinforcing investments in community-level risk reduction.

These five imperatives offer an integrated, actionable agenda for unlocking adaptation investment and delivering impact at scale. They are not isolated elements, but mutually reinforcing levers that strengthen the systems, structures, and incentives needed to move from climate adaptation plans to implementation. At the same time, we must be clear-eyed about the limits of adaptation. Resilience measures are most effective when paired with ambitious mitigation pathways that keep temperature rise within 1.5–2°C, making parallel progress on mitigation essential.

The authors thank the following colleagues for their contributions to this article: Vanessa Bauer-Zetzmann, Jamie Bawalan, Andrew Claerhout, Michael Custer, Sophie Dejonckheere, Greg Fischer, Sahradha Kaemmerer, Min Ai Kok, Olayinka Majekodunmi, Dean Muruven, Tolu Oyekan, Varad Pande, Christian Xia, Annika Zawadzki and Ali Ziat.