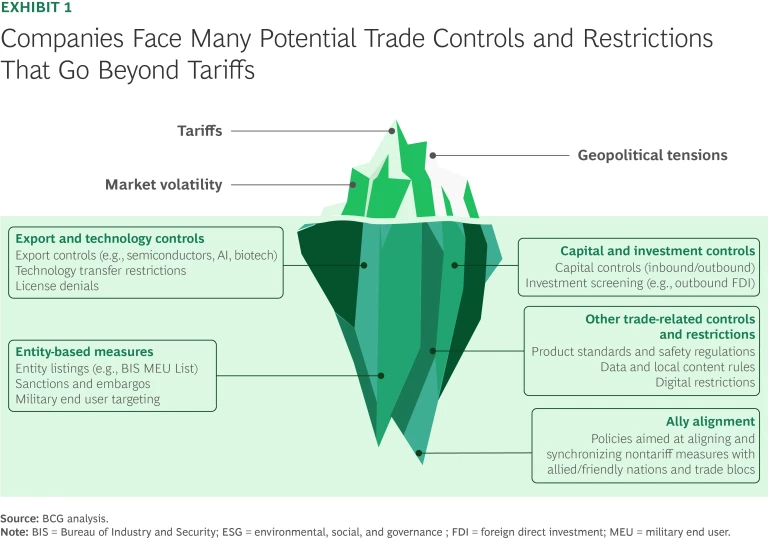

Tariffs grab the headlines and most of the C-suite’s attention, but they are only the tip of the trade iceberg. Global businesses—especially companies in sensitive industries such as advanced manufacturing, telecommunications, defense, and finance—are often subject to other trade barriers, controls, and restrictions. Many of these restraints, which go beyond simply adding cost to a given product, carry far greater impact, including the possibility of closing off entire markets. Because these measures often have a narrower focus than tariffs, they typically do not receive the same level of attention. And because they are usually rooted in statutes, rather than emergency executive authority, as many recent tariffs have been, they may be more difficult to challenge successfully in court.

Companies in affected industries need to move beyond looking only at tariff risk and impact, widening the scope of their global trade lens to encompass other mechanisms for regulating trade. Firms should be thinking about five main types of nontariff barriers, with particular attention to restrictions imposed by trade powerhouses such as the US, China, and the EU, although other global trading blocs and countries use similar policy tools.

A Lengthy Menu

Governments have a broad range of options for controlling or restricting trade. (See Exhibit 1.) Many instruments enable acting with precision, purpose, and permanence, independent of national emergency authority. For example, under the US Trading with the Enemy Act, the president can regulate a wide array of trade and financial transactions with countries that the administration has designated as "enemies." Likewise, although the US–UK trade deal signed in June reduces tariffs charged by both countries, it does not change the UK’s food-related import restrictions such as those on US hormone-treated beef and chlorine-washed chicken. And the Wall Street Journal reported on June 20 that a senior US Commerce Department official has told three semiconductor manufacturers that the administration plans to cancel the waivers under which the chip makers ship US equipment to their factories in China without applying for export licenses.

The most enduring trade policy measures fall into five categories:

- Export and technology controls, which restrict products in sectors such as semiconductors, AI technology, quantum technologies, and biotech

- Entity-based measures, including, for example, the entity list and military end-user (MEU) list maintained by the US Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) as well as licensing bans

- Capital and investment controls that target outbound and inbound flows

- Other trade-related controls and restrictions

- Ally alignment directed toward increasing coordination with allies to enforce these tools

Export and Technology Controls

These measures restrict the export of designated products either generally or to specified countries. The best-known recent examples are US restrictions on the export of certain advanced technology products to China—controls that span the current and previous US administrations—and China’s on-again, off-again restrictions on the export of rare earth minerals and other critical inputs used in multiple manufacturing industries. Restrictions on exports to Russia are an important part of the policy response by the US and many of its traditional allies to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The US has imposed near-total license denial even on low-tech items bound for Russia, underscoring how geopolitical events can rapidly reshape export control regimes.

The rationale for export controls may be rooted in economic, foreign, and national-security policy, and the controls can affect both technology developers (by closing off markets) and users (by constraining supply). Allied countries or blocs, such as the US and the EU, cooperate on export controls through common regimes. In October 2022, the US, the Netherlands, and Japan imposed export controls blocking sales of ASML’s extreme ultraviolet lithography machines to China, closing off a major market and a substantial revenue stream for the company.

Entity-Based Measures

Governments also apply restrictions at the entity or individual company level, which can be a powerful way to regulate trade. Examples of entity-based measures include sanctions (such as freezing assets or limiting market access), export controls (for example, requiring individual companies to seek export licenses for certain products), targeting of state-based companies or industries, and measures designed to combat trade-based money laundering.

The BIS maintains an entity list and an MEU list, among others, of entities that are subject to trade restrictions. In response to US trade actions, China announced entity-based trade measures that included adding a number of specific US companies to China’s Unreliable Entity List. The EU applies entity-based trade measures as part of its Common Foreign and Security Policy. Specific measures include sanctions, arms embargoes, asset freezes, and restrictions on imports and exports of identified goods and services.

Companies that are subject to entity-based trade measures face additional compliance costs and complexities and may need to modify their operations or supply chains to comply. Companies that trade with firms on restricted lists also incur extra costs, since companies exporting to these entities must complete extensive end-user verification. The US Government Accountability Office estimated in June 2023 that enhanced diligence added a compliance burden equivalent to five to ten full‑time employees for a typical major exporter.

Capital and Investment Controls

Governments seek to influence trade patterns and manage exchange rates through trade-based capital controls that regulate the flow of capital into and out of their country. Controls may take multiple forms, including taxes, tariffs, limits, and prohibitions on certain transactions. For example, China strictly regulates the flow of money through restrictions on foreign investment and currency transactions, as well as through taxes on cross-border financial transactions. In recent years, India has eased restrictions on foreign investment, particularly direct investment, but it still maintains controls on capital outflows and certain types of investments. During a period of volatility for the rupee in 2022, the Reserve Bank of India required advance outward remittances for capex-related imports. Affected companies reported two- to four-week delays in working-capital cycles, and one automotive parts exporter cited an additional ₹500 million in working-capital costs during one quarter of the year.

The EU generally avoids capital controls (the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits most of them), but individual members states, such as Greece, have imposed controls during financial crises.

By influencing the cost and availability of foreign capital, controls can affect a country's trade balance and the competitiveness of its industries. For example, restrictions on capital inflows can make it more expensive for foreign firms to invest in a country, potentially reducing imports. Conversely, restrictions on capital outflows can make it more difficult for domestic firms to finance exports. Trade policy and capital controls are often intertwined.

Other Trade-Related Controls and Restrictions

Beyond tariffs and emergency trade powers, governments wield multiple powers to regulate markets and protecting domestic interests. These include product standards and safety regulations, data and local content rules, and digital restrictions, all of which can sharply affect cross-border business, often under the banner of sovereign authority or industrial strategy. For example, new laws in India and China require aviation-related companies, including OEMs, to keep all maintenance, repair, operations, and flight operations data on local servers. To comply with these regulations, OEMs must replicate IT systems regionally, which the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates inflates costs by 15% to 55%, owing to the need for localized data centers and greater regulatory compliance as well as to operational inefficiencies.

Ally Alignment

Countries seek to expand the impact of their trade measures by including allies in established controls or restrictions. The US has tried to enlist allies in coordinated efforts to limit the export of semiconductors and semiconductor equipment to China, which according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, has been effective in constraining evasion. The recently negotiated US–UK trade pact preserves tariff-free treatment for aerospace parts, but it also aligns both sides on denied-party lists—so a component blocked in London is automatically blocked in Washington as well. The EU and the US now coordinate to freeze assets and bar technology transfers to targeted aerospace entities, creating no-go zones for entire supply-chain segments when a single ally tightens controls.

The export control systems in the US and the EU adhere to the provisions of four multilateral export control regimes, which establish common lists of affected countries as well as practices for included governments:

- Wassenaar Arrangement (42 countries)

- Nuclear Suppliers Group (48 countries)

- Australia Group (43 countries)

- Missile Technology Control Regime (35 countries)

Implications for Companies

Unlike many tariffs, statute-based nontariff trade measures typically are not temporary and so can form part of the foundation of a lasting economic policy framework. To prepare themselves for all eventualities, companies need to expand their tariff readiness efforts to include the full array of potential trade measures, including nonemergency levers across sectors and jurisdictions. Compliance programs should cover other potential exposures, such as entity listings (for example, in the US, BIS, MEU, and Treasury Department listings), end-use and end-user checks, dual-use risks, and third-country re-export exposure.

Featured Insights: Explore the ideas shaping the future of business

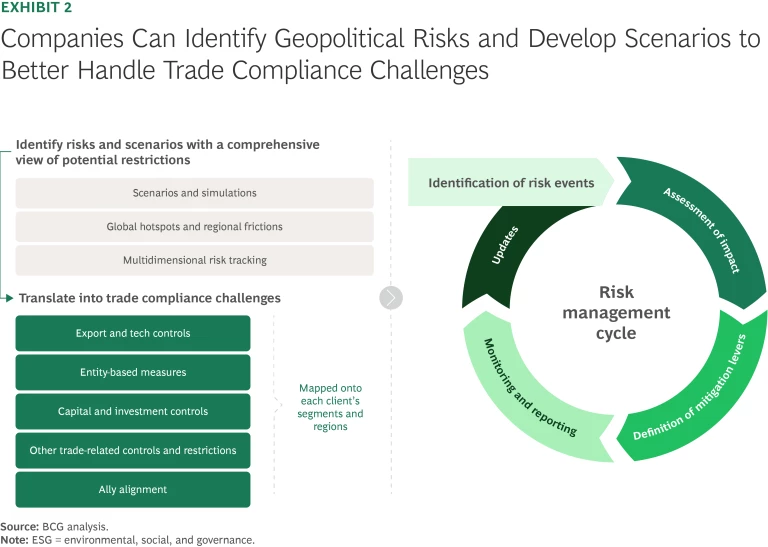

We see more companies identifying risks and scenarios and translating these into trade compliance challenges that the companies can map to relevant business segments and regions. (See Exhibit 2.)

The process typically has four components:

- Taking a Comprehensive View. Management teams need to plan comprehensively for potential trade restrictions, including nonemergency tariffs and other trade measures. They should build all of the necessary capabilities into their tariff and trade command centers and plan across three time horizons: the here and now, the next three to six months, and another six months or more beyond that.

- Scenario Planning. Using scenarios and simulations to anticipate trade risks related to geopolitical shifts and regional tensions is a key element in regulatory preparedness. Companies need to plan not only for their own operations and supply chains but for those of their suppliers as well.

- Compliance Challenges. Translating identified risks into specific compliance challenges, such as sanctions and data localization, will enable companies to formulate mitigation strategies and steps.

- Risk Management. Firms should outline the risk management cycle's integration with specific business segments and regions as part of a customized approach to compliance.

Tariffs have recently become a bigger fact of business life, but they are far from only trade measures that affect global businesses. Companies have a growing need to plan broadly for all trade measures that can disrupt their operations and supply chains.