In the midst of the volatility and uncertainty surrounding emerging markets, two growth economies in Asia keep showing signs of progress. Vietnam and Myanmar are very different countries, in very different stages of economic and political development, but they share similar forward trajectories. In our view, Vietnam is the important emerging market to focus on in Asia today, while Myanmar offers companies with a longer-term perspective a big opportunity to establish a foothold in the growth opportunity of tomorrow.

The Boston Consulting Group highlighted the growth prospects of Vietnam and Myanmar in late 2013, and the trends that we described in that report have only strengthened since then. (See Vietnam and Myanmar: Southeast Asia’s New Growth Frontiers, BCG Focus, December 2013.) Earlier this year, we shone the spotlight on Vietnam’s impressive progress in turning its emerging wealth into well-being, as measured by our Sustainable Economic Development Assessment methodology. (See Lotus Nation: Sustaining Vietnam’s Impressive Gains in Well-Being, BCG report, March 2016.) Now, this article provides an update on the state of economic and political development in these two exciting Asian hot spots.

Vietnam: Approaching Liftoff?

Multiple reasons support the belief that Vietnam is approaching economic liftoff and a sustained period of rapid growth. One is that the country has been growing steadily and attractively for two decades—annual real GDP increases have ranged from 4.8% to 9.3% during that time—as the country has moved from a largely agrarian economy to one powered by manufacturing. (All GDP figures cited are based on World Bank GDP purchasing power parity data, in constant 2011 international dollars.) Moreover, while other economies have faltered in recent years, Vietnam has continued to grow: it has achieved real rates of 5.2% to 6.0% per year since 2012. Yet another reason is that per capita GDP in Vietnam has exceeded $5,000—the level at which growth began to accelerate rapidly in China in 2005, in Indonesia in 1992, and in Thailand in 1988. A fourth reason is that the leadership of the ruling Communist Party has just come through a major change, which points the country toward continued political stability and economic liberalization.

Three other factors underscore the attractiveness of Vietnam right now: the consumer economy, foreign investment and export growth, and room for improvement in productivity.

The Consumer Economy. With a population of about 90 million, Vietnam is the third-largest country in the ASEAN trade block. Vietnam’s wealth is increasing quickly: we expect the number of middle-income and affluent consumers to rise at an annual rate of 13%, increasing from 12 million in 2012 to about 33 million in 2020—a figure that represents about one-third of the population. More significant, Vietnam is among the top performers globally when it comes to converting wealth into well-being: it has achieved a level of well-being that would be expected of a country, such as Indonesia, whose GDP per capita is twice as high. This is a clear indicator that Vietnam has successfully harnessed limited resources for the good of its citizens. The country matches up competitively with other top ASEAN economies in health, education, and economic stability. Internet use is high and rising quickly: some 43% of middle and affluent class (MAC) consumers use the internet, more than in either Thailand (41%) or Indonesia (29%), and e-commerce is gaining a foothold. More than 15% of MAC consumers in Vietnam have made online purchases.

Foreign Investment and Export Growth. Overall economic growth in Vietnam has been fueled by rapidly rising foreign investment and exports, both of which are growing significantly faster there than in other ASEAN nations. (See Exhibit 1.) Top export segments resulting from foreign direct investment (FDI) include telecommunications devices and parts, textiles, computers and electronic equipment, and footwear. Together these four categories made up almost 45% of all exports in 2014. Total exports in 2014 were approximately $150 billion, of which $94 billion, or almost two-thirds, resulted from the FDI sector.

We believe that the manufacturing economy is set to undergo a major expansion. Vietnam’s labor force is well educated. The country’s most recent scores on the Programme for International Student Assessment—which tests proficiency in math, science, and reading—equaled or surpassed those of Germany. Vietnam also enjoys a significant cost advantage over other emerging markets. In 2015, the average annual salary for a Vietnamese manufacturing worker was $3,900; for a manager, it was $12,900. These salaries compare, respectively, with $4,300 and $14,800 in Indonesia; $5,300 and $22,500 in Malaysia; and $8,700 and $24,400 in China.

These factors have been attracting increasing levels of foreign investment to Vietnam in recent years, with Japan leading the pack until 2014, when it was overtaken by South Korea. Major companies such as Bridgestone, Panasonic, Sapporo, Samsung, and LG are investing. Samsung alone has pledged more than $12 billion. Two projects in Bac Ninh Province have attracted more than 40 South Korean subcontractors and spare-parts suppliers. LG launched a $1.5 billion appliance manufacturing facility in the Trang Due Industrial Park in Hai Phong; it is the company’s largest manufacturing base in Southeast Asia.

A recent survey by the Korea International Trade Association involving 540 South Korean companies found that Vietnam was the top destination for South Korean investors. The implementation of the Vietnam-Korea Free Trade Agreement in late 2015 is likely to promote further investments.

One big question is whether foreign investment in Vietnam will continue to be driven primarily by its Asian neighbors. A development that may change the game is the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), signed in February 2016, which would facilitate more US investment. Many large and diverse US companies are operating in Vietnam, including Intel, Microsoft, American International Group, Coca-Cola, Procter & Gamble, and ConocoPhillips. During a recent visit to Vietnam, President Obama attended a signing ceremony for new US-Vietnam commercial agreements valued at more than $16 billion. But the aggregate amount of US investment in Vietnam remains small compared with that of US companies’ first destination in the region: Singapore.

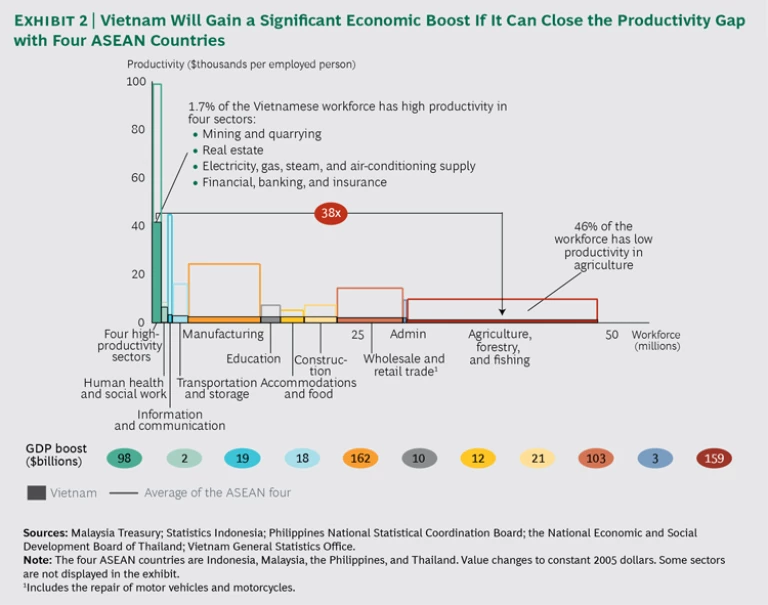

Room for Improvement in Productivity. There is ample room in Vietnam for productivity growth, which could have an enormous overall impact. Simply raising productivity to the level of the top ASEAN performers (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand) in three major sectors of the economy—manufacturing, wholesale and retail, and agriculture, which together employ some 39 million people—would add almost $424 billion to Vietnam’s 2015 GDP. (See Exhibit 2.)

To be sure, Vietnam also has its challenges. In addition to low productivity, the economy is still substantially agrarian, and infrastructure development lags that of other Asian nations.

Outlook. It’s hard to see how the country will not at least sustain the levels of growth that it has produced in recent years; indeed it is much more likely that growth will accelerate as Vietnam addresses its challenges and as foreign capital seeks to take advantage of one of the world’s highly attractive opportunities. Implementation of the TPP trade pact should provide an additional boost. We expect Vietnam to attract even higher FDI given its position as the lowest-cost manufacturing country among current TPP members, and it will benefit from the opening of major markets, such as the US and Japan, for its exports.

Myanmar: Tomorrow’s Hot Spot?

If Vietnam is a story of steady progress over time, Myanmar is a tale of fast-paced transformation. This is especially true in the political sphere, where the country has moved from a highly authoritarian, closed regime to a largely open, mostly democratic system of government in just a few years. After five decades of military rule, many are optimistic about the future, but plenty of questions remain. One is whether the political changes will be allowed to take root and flourish; Myanmar has little experience with democracy and few of the requisite institutions of representative government. Another is how fast economic reform and growth can follow the political liberalization. Today much of the economic activity in the country remains controlled by a small number of organizations, and financial inclusion lags the extraordinary improvements in political liberalization.

But there are good reasons for optimism. After shunning Myanmar for decades, the outside world is now pulling hard for its success, and assistance—economic, financial, technical, and political—is readily available. The main limiting factor is the fledgling government’s capacity to handle the help it is being offered. After years of economic stagnation, Myanmar saw a strong upturn that supported economic growth (albeit from a relatively small base) at an average annual rate of more than 5% over the past 20 years. And its growth has continued in recent years at rates of 7.5% to almost 9.0% while other Asian and emerging economies have slowed down. The country’s MAC population is expected to increase by 8.5% per year between 2012 and 2020, growing from 5.3 million to 10.3 million.

Myanmar represents a longer-term bet than Vietnam. Myanmar is still very much an agrarian nation, with two-thirds of the population working in agriculture. Productivity is poor, making the sector a big opportunity for high-impact growth and transformation.

That said, the changes taking place in the nation of 50 million people have caught the attention and interest of many multinational companies. FDI is climbing. So far, infrastructure is the primary focus—two-thirds of the foreign funds invested or pledged (more than $40 billion) have gone to oil and gas and power. Manufacturing has attracted about $6.6 billion, and tourism has brought in $2.4 billion.

As is true in Vietnam, the big investors in Myanmar so far—China is the largest—have been mainly Asian, although we expect the investor mix to evolve in the coming years as more domestic markets open up. In one possible scenario, similar to the pattern that took place in Vietnam, some countries—Japan and Korea, perhaps followed by the US—start to increase investment. The Thilawa Special Economic Zone, for example, has been constructed with support from the Japanese government and Japanese companies, including Mitsubishi Motors, Marubeni, and Sumitomo, as well as the Japan International Cooperation Agency. Built at a cost of $1.5 billion, the special zone is expected to host 100 factories employing some 40,000 workers when it becomes fully operational in 2017.

In another possible scenario, Southeast Asian regional partners that are familiar with navigating the local rules and regulations accelerate their investments. For instance, Vietnam-based Viettel plans to invest $1.5 billion in Myanmar to develop the telecom sector, and the company recently won its fourth telecom license.

Regardless of how foreign investment plays out, we expect the next five years in Myanmar to be characterized by volatility, with progress determined to a significant degree by how quickly the government can expand its capacity to handle the aid and investment on offer. There will likely be surges in opportunity, such as those now in the travel and tourism sector, mixed with periods of uncertainty, especially in the political realm. Companies that want to play a long-term role need to start now, establishing a presence, building relationships, and developing trust.

They might, however, encounter a crowded playing field. Two-thirds of Japanese companies, for example, say that they plan to expand their presence in Myanmar in the next one to two years. Foreign companies that try to wait out the inevitable growing pains and swoop in later to cherry pick the rewards may find themselves on the outside looking in.