This article is based on “Influencing Outcomes in a Consolidating Insurance Industry: Three Keys to Value Creation,” by Pia Tischhauser, published in January 2016 in The Geneva Association’s Insurance and Finance Newsletter.

Although not quite at the stage of mania, mergers have been sweeping the global insurance industry. Exor-PartnerRe, Willis Group–Towers Watson, Willis–Gras Savoye, ACE-Chubb, and Anthem-Cigna are just a few of the high-profile transactions announced over the past year.

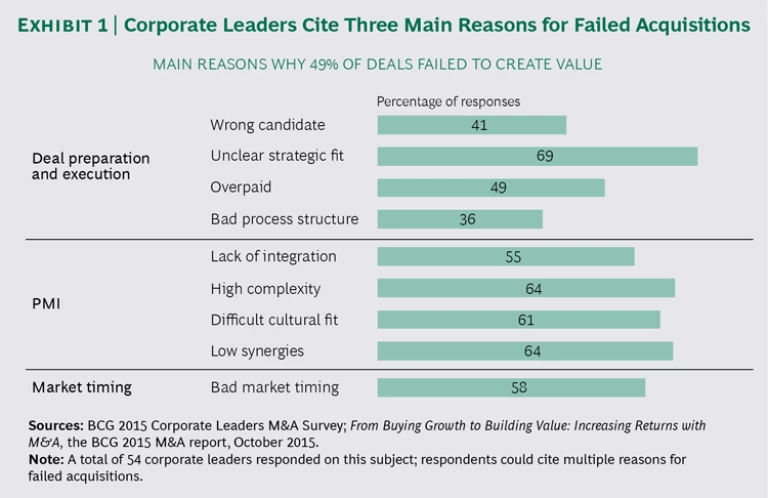

Behind the headlines, however, lies a stark reality. The Boston Consulting Group’s analysis of one-year relative total shareholder return in 778 transactions involving insurance companies between 1990 and 2014 found that only 51% created value and 49% actually destroyed value. In other words, the odds of success are similar to those in a coin toss. The half of insurance deals that failed to deliver value had fallen prey to a variety of culprits. (See Exhibit 1.)

Insurers can do better. Our experience with companies throughout the industry shows that acquirers can tip the playing field to their advantage. The keys to success in insurance M&A relate to strategy and target analysis, deal execution, and postmerger integration (PMI). This article explores how to apply this framework.

Multiple Forces Drive Consolidation

A multitude of macro-level forces will continue to propel consolidation in insurance over the next five years or more. They include more stringent regulatory requirements, continued low investment yields, new entrants, rapidly advancing technology, and limited growth opportunities.

Regulatory requirements, especially those having to do with capital adequacy (the EU’s Solvency II Directive is one example), continue to intensify, putting pressure on both independent insurers and conglomerates. The provisions of the EU’s Insurance Mediation Directive 2 (IMD2), which the EU says “is designed to improve EU regulation in the retail insurance market, increase consumer protection, and improve consistency between the regimes operating in the different member states,” must be written into member states’ national law by early 2017. Among other things, IMD2 will likely decrease some consumers’ willingness to pay for financial advice at current levels.

Interest rates as well as investment yields are likely to stay low for some time (at least in mature markets), making profits in traditional life insurance difficult.

New entrants as varied as supermarket chains and telecommunications companies are in a position to disrupt the insurance value chain: they have a powerful asset in the customer data they collect, and they own the “last mile” link to the customer. New operating models are making it difficult for incumbents to play across the entire value chain. The incumbents are vulnerable to specialists that disrupt existing models—one example being online aggregators that offer consumers a variety of price-transparent product choices from multiple providers. Large incumbent players are best placed to make the investments needed to fend off such assaults. Midsize insurers that still handle all aspects of their business internally are especially likely to feel the competitive heat.

Insurance companies are prime candidates to exploit insights into customer behavior and needs, but building the necessary big-data technology, culture, and teams is cost prohibitive, especially for smaller players.

Insurers face limited opportunities for growth. Mature markets are consolidating, and, although the risks that consumers face are expanding (data security, for example), the industry hasn’t succeeded at demonstrating the need for coverage beyond the most basic. Emerging markets offer potential for growth, but they have their own complexities; building a presence organically can be slow and difficult; and near-term profitability is a challenge. Scale in new markets can be achieved most realistically through acquisition.

Three Steps to Creating M&A Value

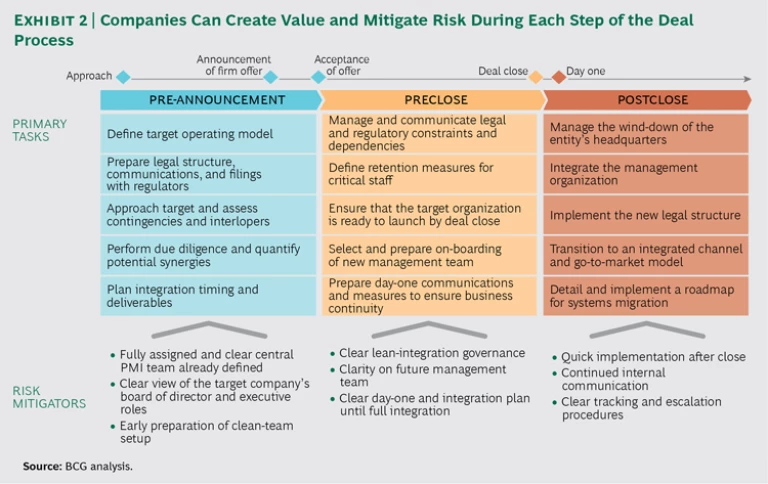

Creating value—and mitigating risk—through M&A in insurance, as in other industries, requires three steps: rigorous strategy and target analysis, strong deal execution, and effective PMI. (See Exhibit 2.)

Rigorous Strategy and Target Analysis. Many insurance acquisitions are made opportunistically, in a time-pressurized window, and often with an investment bank serving up the target. Candidates are analyzed largely on their financials, but this assessment is only one component of a successful acquisition. Smart acquirers actively seek out proprietary deals, employing a proven, systematic approach and an analytical framework. They think through all aspects of a merger before initiating the transaction (including potential bids by competitors and other interlopers).

Two of the reasons for failed acquisitions cited most often by respondents to BCG’s 2015 Corporate Leaders M&A Survey were unclear strategic fit and lower-than-expected synergies. Acquirers should be able to surface both of these issues with a disciplined review-and-selection process. In our 2015 M&A Report, we recommended five imperatives to guide the target selection process:

- Understand industry dynamics, including the factors influencing the direction of the industry in the next five to ten years.

- Don’t pursue M&A without a strategy. A sound portfolio analysis is the starting point for a target search.

- Follow a systematic approach and focus efforts on quantifiable value creation. Pay particular attention to the strategic fit between candidate and acquirer.

- Be rigorous: invest the time required to analyze targets in depth.

- Embed the search process in your organization. Approach the search as an opportunity to set up a permanent screening process for future acquisitions.

A company may need to devote more resources and attention to a small deal in an emerging market than to a much larger transaction in its home market. Cultural and market differences complicate integrating the two companies’ businesses, which is a prerequisite to realizing synergies. (See “From Acquiring Growth to Growing Value,” BCG article, October 2015.)

Strong Deal Execution. Deal teams are driven to complete deals. Rigorous due diligence can reveal that acquisitions that initially looked attractive are not. Acquirers should focus on assessing key value drivers during the due-diligence period and walk away from a deal if future value seems unlikely to be realized. “We have already invested so much time” is not sufficient reason to complete a poorly conceived transaction.

Acquirers also need to gauge a deal’s impact on the current business by conducting a side-by-side analysis of their company and the target. They should also run a simulation of the deal in order to understand the transaction’s effects on their financials and market position. In addition, they should look closely at the correlation between risks on the two balance sheets, as well as at how markets and customers are likely to react.

Effective PMI. Many of the reasons for failed acquisitions involve what happens after a deal closes. These include lack of integration, high complexity, difficult cultural fit, and low synergies. Plenty of companies struggle to integrate fully after the deal. Synergy targets that were so enticing in the run-up melt away under the realities of meshing two very different organizations in a short time.

PMI is one of the hardest challenges that senior executives face. It is a complex undertaking, often involving multiple simultaneous changes in a company’s business processes, organization structure, and management personnel. Bringing together two organizations, each with its own culture, norms, and behaviors—while protecting day-to-day cash flow—is a corporate mission unlike most others. And while most executives believe that they know how to integrate properly—and stand ready to devote the necessary resources to making sure PMI gets the attention it requires—they often find that they either overestimated their preparedness or underestimated the challenges. In most organizations, PMI is not a core skill. It requires considerably different talents and capabilities than conventional line management, and every situation is different.

Inexperienced deal teams often do outside-in estimates of synergies and integration costs, failing to include business and operations people in the discussion. Effective PMI requires considering integration—of businesses, people, processes, and technology—from the start of the due-diligence period. Realistic synergy expectations can be formed only when there is operational experience on the deal team. Including deep insurance-industry knowledge in the planning for, and execution of, PMI can accelerate downstream value creation.

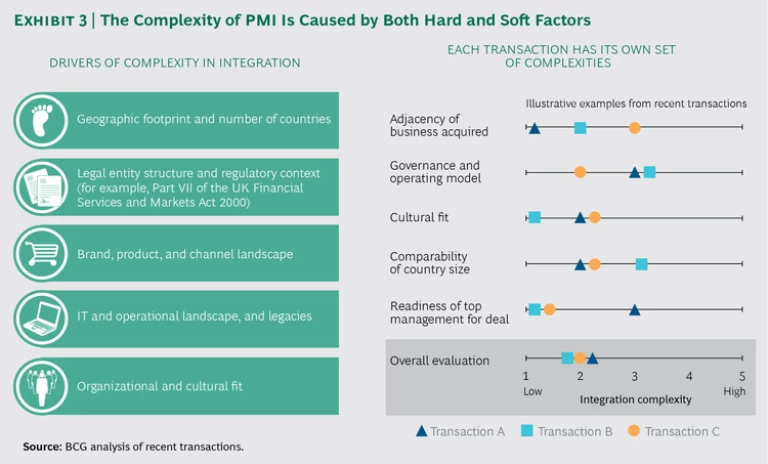

A best-practice approach to preparing for integration examines five critical factors:

- Geographic Footprint and Number of Countries. Sometimes mergers do not deliver economies of scale owing to profound differences across the countries in which insurance companies operate and the business models in those countries. The success of the merged company depends on managing the integration process to derive synergy.

- Legal Entity Structure and Regulatory Context. Ideally, the merged entity should operate as one legal entity. There can be numerous legal and regulatory hurdles to this goal, however. For example, in the UK, Part VII of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 enables a book of insurance policies to be moved from one legal entity to another, but this can be complex and take time to execute. For some purposes, reinsurance will suffice, but if the acquirer wants to separate the policies permanently from the transferor, reinsurance is insufficient and a more structured approach is required. This is just one example of a PMI issue that is best assessed before the acquirer makes an offer to the target.

- Brand, Product, and Channel Landscape. M&A financial analyses often overlook issues related to the target’s brand, products, and distribution channels. Insurance companies have some of the most recognizable branding in the world, representing significant equity, and these factors need to be taken into account. The transition from two brands to one in the combination of AXA and Winterthur has taken almost four years. Distribution channels present a similar issue: some companies have brokers, others have their own agents, and still others sell directly to consumers. These important tactical matters can quickly become thorny; they need to be thought about in advance, since they can sometimes turn out to be deal breakers.

- IT and Operational Landscape. Most insurers’ IT shops are heavily weighted toward legacy systems. On paper, their costs may appear low and thus attractive, but acquirers will inevitably need to invest heavily to upgrade core business systems. Such an investment affects ultimate value and can substantially alter the terms of a deal.

- Organizational and Cultural Fit. Companies should pay particular attention to the organizational and cultural fit between candidate and acquirer. A high number of adjacencies in lines of business enable the acquirer to evaluate a target most effectively. For example, a company that sells auto insurance (short-tail products, high turnover, and an automated sales process) will have difficulty assessing the potential value of a low-adjacency target that sells B2B commercial insurance, using qualified underwriters and a high-touch sales process.

The impact of organizational and cultural fit cannot be overestimated. Deals can span a wide spectrum of complexity, with each transaction encountering a variety of hard and soft factors. (See Exhibit 3.) In some instances, complexity more than overwhelms financial attractiveness.

The Role of the “Clean Team”

In many M&A transactions, a “clean team” ensures that sensitive competitive information and data on the target company’s business, which are prohibited from disclosure before the deal’s close, are fully captured. The team is responsible for collecting, safeguarding, and analyzing the relevant data—and presenting recommendations to the acquirer. A typical approach is for the team to be composed only of advisors or company executives who are not involved in commercial, strategic, or pricing decisions. The team’s analyses are shared only on an aggregated level prior to closing. After clearance, the clean team can facilitate fast information exchange between both parties. A clean team is particularly relevant in insurance M&A, where antitrust concerns may delay an acquisition.

While the three steps to creating value are essential in their own right, their application within a coordinated timeline mitigates risk and unlocks the true potential for M&A value.

By following such a rigorous approach—and focusing on the three steps—insurance industry acquirers can dramatically boost the odds of long-term success.