Value-based health care is no longer just a theoretical model—it’s a real movement starting to transform the way health care is managed. Payers, hospitals, and clinicians around the world are increasingly measuring and reporting patient outcomes to improve care. Major players—including Medicare and Medicaid in the U.S., the National Health Service in the UK, the National Health Care Institute in the Netherlands, and several leading European university hospitals—have all made great strides in this area.

As more payers and providers make value-based health care a central part of their management models, they face the challenge of defining and selecting the right outcomes to measure and report. Few conventional metrics reflect a patient’s real-world outcomes: immediate treatment consequences, the recovery process, state of mind, and the return to good health. Through our work with payers and providers globally, we developed a set of principles to help clinicians and leaders measure the outcomes that really matter to patients.

Defining Outcomes

In his pioneering article, “What Is Value in Health Care?,” Michael E. Porter highlights the importance of outcomes measurement as a critical element of health care reform. Porter defines outcomes as “the results of care in terms of patients’ health over time.” Building on this framework, ICHOM, a nonprofit organization, has defined outcomes as “the results people care about most when seeking treatment, including functional improvement and the ability to live normal, productive lives.” The organization has defined and published 12 global standards for outcomes measurement so far. Developed by leading clinicians, registry leaders, and patients around the world, ICHOM’s metrics for major medical conditions focus on the outcomes that matter to patients.

We agree with ICHOM’s definition and believe that outcomes must put patients at the center, focusing on what they experience while coping with a health condition. This mind-set is critical when developing a strong set of metrics.

For example, health care teams are currently trained to focus on whether a treatment is effective. But to understand how a treatment impacts a patient’s quality of life, physicians need to ask, “Are you feeling anxious or hopeful? Are you sleeping, eating, exercising? Can you do the things you enjoy?”

More specifically, for a patient with prostate cancer, for instance, the immediate outcomes that matter may be overall survival and progression to metastasis. But nearly 95 percent of patients survive the first five years after diagnosis, so quality-of-life issues—such as complications from surgery, pain, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction—must also be taken into account. If a tumor is small, and the patient is of advanced age, the right choice may be active surveillance—that is, not removing the tumor but tracking its progression closely. In this scenario, the patient’s anxiety about living with untreated cancer is a critical metric. These experiences highlight outcomes that can and should be measured.

Most Conventional Metrics Do Not Measure Outcomes That Matter to Patients

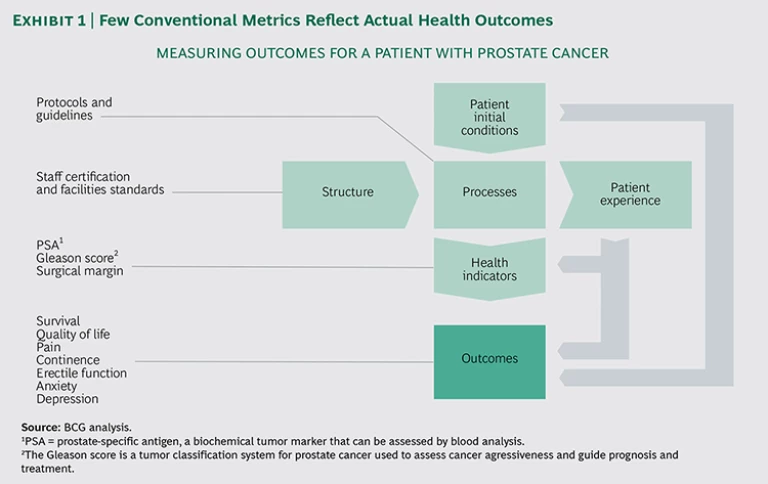

We can measure many things as we try to understand the quality and efficiency of health care, but very few conventional metrics currently tracked by providers reflect actual health outcomes. (See Exhibit 1.) For this reason, it is important to distinguish between conventional measures and the outcomes that matter to patients. Conventional measures include the following:

- Patient Initial Conditions. A patient’s initial baseline—such as age, comorbidities, and other risk factors (for example, use of medications or substance abuse)—are essential to the individual’s medical history. They inform adjustments of treatments and are critical when comparing outcomes across different institutions. When patient cohorts are compared, the baseline reflects differences in patient mix and should be used to adjust outcomes on the basis of risk.

- Structure. Providers may also track structural metrics, such as staff-to-patient ratio, staff competencies, and the state of providers’ facilities. While these metrics may highlight areas of relative weakness or risk, they typically do not reflect patient outcomes.

- Processes. Providers commonly track treatment protocols, such as time of biopsy, time to diagnosis, surgical technique used, radiation treatment settings, medication administered, and so forth. These process measurements can be used to monitor adherence to clinical guidelines and help shed light on how different methods lead to different outcomes—some better than others. Yet focusing solely on optimizing process measures shifts attention away from what is really important to a patient and can discourage innovation or the adoption of new methods that could benefit patients and improve outcomes.

- Patient Experience. Hospitals are rightly concerned about patient satisfaction with care, and many use patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) to evaluate satisfaction. PREMs assess a patient’s experience with certain aspects of his or her care, including the attitude of clinical staff, quality of hospital food, waiting times, and cleanliness. These surveys may be useful to drive improvements in the patient experience.

- Health Indicators. For many conditions, short-term outcomes may be hard to measure. Indicators known to predict outcomes can thus be very important. For a patient with localized prostate cancer, for example, the provider may measure surgical margin, prostate-specific antigen (a biochemical tumor marker), and the Gleason score (a tumor classification system for prostate cancer). These metrics are all important indicators of health and may help predict the results that matter to patients, but in most cases they are not a sufficient substitute for outcomes.

All of these conventional metrics play an important role in health care: they provide vital data and, when strongly correlated with outcomes, they ensure a powerful and balanced set of metrics. But it is important to recognize that when used in isolation, without an adequate focus on outcomes, such metrics can be misleading and prevent management and clinical teams from focusing on what really matters to patients.

Principles for Selecting the Right Outcomes Metrics

Payers and providers accustomed to process metrics may find it challenging to shift gears and identify the outcomes that matter to patients. (See “Test Your Ability: Which Measures Would You Choose?”) For this reason, we have developed the following set of guidelines to facilitate the process of selecting outcomes metrics.

TEST YOUR ABILITY WHICH MEASURES WOULD YOU CHOOSE?

Choosing the outcomes that matter to patients can be challenging. For this reason, we have put together a brief exercise that will test your skills and inspire further reflection on how to define outcomes.

From the list of metrics offered in the exhibit below, select five that you believe should be used as outcomes metrics for patients with localized prostate cancer. All suggested measures relate to prostate cancer and could be meaningful to measure, but not all measures reflect patient-centered outcomes.

(Answers can be found at the end of the exhibit.)

Measure outcomes for well-defined populations. Outcomes should be measured for all patients within a well-defined population segment (such as those with coronary artery disease) regardless of how their condition is treated (such as with percutaneous coronary intervention, bypass surgery, or pharmaceuticals). In value-based health care, it is fundamental to compare the outcomes of different clinical teams rather than the outcomes of different procedures, although the latter may ultimately provide an important explanation for differences in the results achieved. For example, disease registries that focus on a particular procedure and compare outcomes across centers have played a very important role in improving hip and knee arthroplasty, providing critical insights into the most effective implants and surgical techniques. However, data that compares varying procedures cannot answer the broader question about the optimal treatment for the underlying disease of osteoarthritis. Both perspectives are valuable, but measuring outcomes based on the medical condition will challenge the current treatment paradigm and enable innovative changes in clinical practice.

Measure outcomes across the full cycle of care. Metrics should track every stage of a patient’s journey, including prevention, diagnosis, treatment, recovery, follow-up, and long-term well-being. It is also important to make sure that measurements track the full range of care providers, including primary care, specialized care, and rehabilitation. This ensures that insight is gained into the complete range of outcomes for a patient group and that differences in health outcomes caused by variations in the configuration of health systems or care pathways can be assessed.

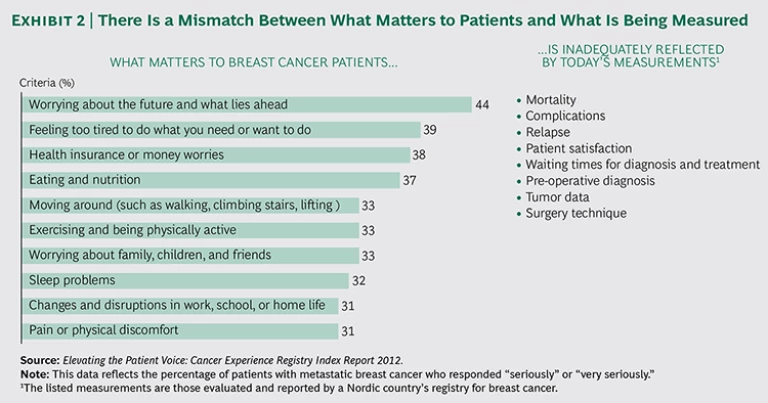

Define outcomes based on what matters most to patients. There can be a stark difference between what providers and registries measure and what patients actually care about. For example, measures of the clinical process—such as the number of admissions, length of stay, and interventions—often do not matter as much to patients as do measures of quality of life, functional ability, and emotional well-being. Exhibit 2 demonstrates the extent of this mismatch for breast cancer patients. The primary concerns for breast cancer patients are worrying about the future, being tired, and health insurance or money worries.

Direct reports by patients on the status of their own health can help determine whether treatment culminates in outcomes that patients care about. For this purpose, many providers rely upon patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs). The Martini-Klinik, in Hamburg, Germany, uses Web surveys to follow up on clinical outcomes for prostate cancer treatment; response rates are typically above 80 percent. Because PROMs capture a patient’s personal, unfiltered assessment, with limited demand on the clinician’s time (and untainted by the clinician’s influence or interpretation), these tools provide a useful complement to clinical measurements and assessments.

Patients’ perspectives are critical when defining outcomes. By including patients, several leading organizations have established targeted, patient-centered outcomes metrics for specific diseases. All 12 outcomes standard sets published by ICHOM, for example, have been developed by working groups that include patient representatives. Some hospitals, too, have conferred with patients when defining outcomes metrics. For instance, in a working group for bipolar disorder at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, in Gothenburg, Sweden, a patient suggested that self-sufficiency was a significant desired outcome. Bipolar disorder is often linked to damaged relationships, poor job or school performance, and even suicide. But when correctly treated, patients living with this illness can lead full and productive lives. By measuring self-sufficiency as an outcome, physicians in Sweden can evaluate how well patients are coping with the disease and whether they need additional support.

Choose measures that are already standardized and included in registries before working to create new metrics when possible. The more comparable the outcomes data among providers, the more useful they are. Physicians in Australia, Sweden, the U.S., and other countries are using comprehensive outcomes data collected in national disease registries to identify outliers and improve average outcomes. Indeed, ICHOM plans to expand its current 12 metrics to cover more than 50 conditions by 2017, representing approximately 70 percent of the disease burden in industrialized countries. These standard sets can—and should—be leveraged by providers and payers. By selecting standardized outcomes metrics, health care systems can compare outcomes and variations in medical practice within a hospital or across provider networks regionally, nationally, and internationally. With standardized metrics, providers have a broader base for identifying best practices. We therefore recommend that organizations begin by reviewing existing standards and then, if needed, complement them with additional metrics that the providers want to follow (because of, for example, a specific local research or development effort).

Prioritize the most important outcomes—and avoid selecting too many. It is important to prioritize and select the metrics that will have the biggest impact, because requiring clinical teams to track too many of them will burden the teams with an overly complex data-collection process, which could lead to limited compliance and poor-quality reporting. We recommend selecting seven to ten metrics for analysis per patient group. Of course, additional metrics can be tracked to further analyze and understand the results, but they should not be prioritized for steering.

In general, select measures that can be tracked easily, but do not choose convenience over relevance. When starting out, it may make sense to select certain outcomes measures that can be tracked easily to gain traction with systematic monitoring and analysis. But working toward the goal of tracking the most relevant measures is important, even if it requires more effort.

Once outcomes measures have been selected, make sure to avoid any ambiguity in the implementation. The team must define in advance the exact patient group that will be included in the measures, which tools will be used (such as doctor-reported data, electronic medical records, PROMs, and registries), how data will be collected, who will report the data, and when the data will be gathered, analyzed, and reported. Defining all of these factors up front removes ambiguity during implementation and increases the likelihood that comparative analysis will yield high-quality data.

Putting the Principles into Practice

Selecting the right outcomes measures should be a carefully planned process to which key stakeholders devote time and attention. When done right, outcomes measurement and transparency can boost health care value and enable providers and health care systems to better serve patients through continuous improvement. A poorly designed process leads to inadequate metrics, which can undermine efforts, distort results, and disengage medical professionals.

We recommend the following steps and considerations to successfully put these principles into practice:

- Establish a cross-disciplinary team. Involve representatives—including nurses, primary care physicians, surgeons, and other providers—from all key specialties and functions along the care pathway for a selected patient group to ensure that all voices are heard. Controllers and data system specialists should be brought on board to share expertise regarding the best ways to extract and analyze the data and help manage the new demands on clinical teams.

- Involve patients in defining metrics. Patients can ensure that outcomes measures address what really matters to them. They can also help select and test PROM tools. Patients create a positive dynamic and keep working groups focused on the outcomes that matter during treatment, recovery, and over the long term.

- Collect a comprehensive list of available metrics. Review the existing international standard sets (such as those developed by ICHOM), national standards (disease registries recognized by leading experts), and any metrics already being used by patient groups for different conditions, because they may be applicable to the patient group that is being measured.

- Review recent research and publications. Conduct a review of the literature to understand the importance of various measures and to identify any innovative metrics or measurement techniques.

- Prioritize the most important metrics. After creating a comprehensive list of measures, use the team’s expertise and the latest research to prioritize the metrics that matter most to patients. We recommend a core set that is fully aligned with international standards, complemented by a few institution-specific measures.

Nearly all patients seek the same health-care outcomes: to be self-sufficient, symptom free, and capable of pursuing the activities that give them a sense of satisfaction without interference by their medical condition. If payers and providers measure outcomes based on these essential human needs, significant progress will be made in the areas that most deeply affect patients and their families. Identifying and measuring the right outcomes requires work, but meaningful improvements are already emerging as a result of tracking the outcomes that matter to patients.