Applied to everything from fast food to cable TV, bundling offers businesses a tried-and-true way to cross-sell—that is, to sell more things to the same customer. In exchange for a lower price, buyers purchase all the items in the bundle—the burger, fries, and drink, for example—rather than buying each one separately.

Bundling is a particularly good tool in dynamic markets like technology, media, and telecommunications (TMT), which feature a constant innovation cycle and converging market segments. In such an environment, companies are always looking to leverage their strength in one segment to grow in another—computing into consumer electronics or enterprise software into cloud services, for example. They often use bundling as a strategic weapon to combine a product that has a large market share with one in need of greater penetration. Additionally, companies that are already present in a market but haven’t yet been successful may want to emphasize the complementary nature of their products by creating a “better together” value proposition.

But despite the attractiveness of bundling in TMT markets, companies too often fail with this strategy, for four major reasons:

- Customers are not convinced that the bundle meets their needs.

- The price of the bundle is not compelling enough compared with the price of the bundle components purchased separately.

- The process of buying the bundle is too complicated.

- The bundle does not generate incremental profits.

Bundling decisions in the TMT space can be complicated. Below we offer four simple yet powerful rules of the road that can give leaders a clear sense of when bundling makes sense.

The Economics of Bundling

Selling a bundle of products and services has become de rigueur in TMT markets, for a number of reasons. For one thing, these markets have a long history of companies moving into adjacent businesses to secure additional growth prospects. Technology companies, in particular, often sell complex solutions, and CIOs and other decisionmakers may prefer to purchase combinations of offerings, such as hardware and services, rather than making numerous individual decisions. The best solution, for both the company and such customers, might be to add a new attach product from an adjacent business to a well-established core product that customers are already buying.

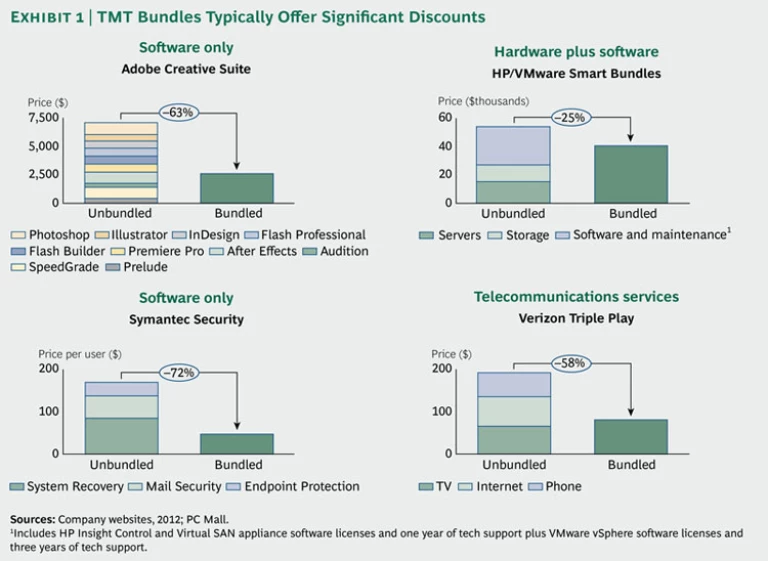

But the dynamics of TMT markets make bundling different and more challenging than it is in other markets. TMT companies often earn high gross margins—from 30 to 80 percent. To convince customers to choose a bundle instead of buying individual components separately, companies must offer a discount. For bundles in which the core product has a low marginal cost—for instance, high-margin products such as software—typical discounts range from 60 to 70 percent, while discounts of 25 to 40 percent are offered on bundles in which the core product—such as low-margin hardware—has a high marginal cost. (See Exhibit 1 for four illustrative examples.)

With high-volume, high-margin products, companies can afford to offer a big discount, particularly when the bundle eliminates the cost involved in selling each product on its own. But a bundling discount that is too large will wipe out any incremental profits gained from products added to the bundle.

In the business-to-business space, the common practice of offering highly variable discounts makes it even harder for bundling in TMT markets to succeed. Negotiated discounts can vary between 40 and 70 percent. If a company sets the bundling discount at, say, 55 percent, many customers will not find it sufficiently attractive. Yet if the bundle discount is 72 percent, for instance, the company will be giving away too much to too many customers.

There is an additional challenge: complexity. Consider a company that has 20 servers, each running a different type of application software. In effect, the company has 400 possible bundle configurations and discounts. Add another dimension to the bundle, and the number of SKU configurations expands exponentially, generating too much complexity for the sales force or pricing system to manage. The issue is how to identify those few combinations among thousands that could be successful.

Last and least obvious, internal incentives can be misaligned. For example, the general manager of a successful, highly valued product might be concerned that offering a bundle containing a newer product would erode profit margins. There might also be no mechanism available that would allow different divisions to reach agreement on how to split the cost of the discount. And salespeople might not find it worthwhile to make the extra effort needed to sell a new product with which they’re relatively unfamiliar.

In short, bundling is hard to do well.

Making Sense of Bundling

Managers are often familiar with the traditional approach to bundling. The process typically involves identifying complementary offers, performing a correlation analysis of products and services that are purchased together, and conducting a conjoint analysis to determine the profit-maximizing price. But companies often either cut corners with these analyses or do not perform them at all. And their bundles end up failing.

We have devised a simple checklist of four rules for bundling in TMT markets. Companies that do not have the time to perform the traditional correlation and conjoint analyses should apply this checklist systematically. In cases where these analyses have been done, the checklist can be used to double-check them.

Bundle products that provide the customer with a clear better-together value proposition. Adobe has created a popular bundle in the Adobe Creative Suite—including Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, and Flash—that gives designers everything they need to create work both in print and online. Symantec offers small and medium-size businesses security suites that cover security and data recovery needs for e-mail and mobile devices.

One of the reasons bundles fail in the marketplace is that customers don’t appreciate their benefits. For instance, they may complain that the technical support and customer service for the bundled products feel like they are provided by separate companies, so there is no advantage in buying the products in a bundle. Companies that bundle well put together products that offer a unified customer experience, target the need of a specific market segment in a differentiated way, appeal to similar kinds of decisionmakers, and meet the needs of buyers at the exact stage in the purchase cycle that they are in.

Focus on attach products with low penetration but high potential. Effective bundles often combine a new attach product from an adjacent business—one that has broad appeal—with one of the company’s own well-established core products. The success of many cable and telephone companies, for example, has stemmed from their ability to bundle Internet broadband services with the cable TV and phone services that consumers were already buying. As broadband penetration approached the saturation point and bandwidth improved, these companies increased their presence in voice and TV, respectively, and began offering “triple play” TV, phone, and Internet bundles. Major cable and telephone companies that in 1999 held less than 15 percent of the U.S. and U.K. Internet service provider (ISP) markets effectively leveraged their infrastructure and a better-together value proposition to gain share in the ISP market as it shifted to broadband. By 2011, they represented more than 65 percent of the Internet broadband market in both the U.S. and the U.K.

A contrasting scenario would be one in which an attach product already has a high penetration—of 50 percent, say. Even if the company were to gain a 100 percent share of the market (an extremely difficult feat), the economics would still not work, because the 50 percent discount that this would require would cancel out the increase in revenue. Rather than giving a big discount to a few people in order to increase penetration, the company would be giving a big discount to a large number of people, eroding margins on the existing customer base and making the bundle unlikely to generate incremental profit overall.

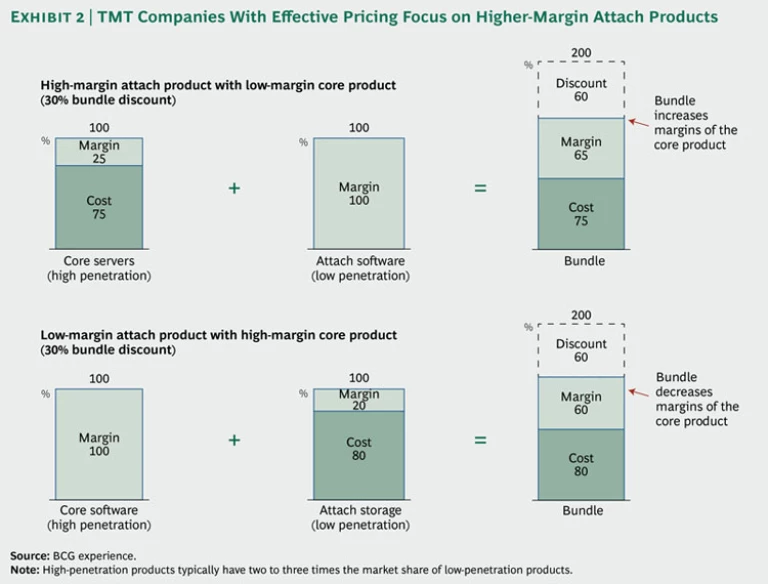

Stick with higher-margin attach products. So far, we have focused on volume considerations, but it is also critical to think about the relationship between the margins of the various products in a bundle. Bundling usually has a positive impact if either the margin of the attach product is higher than that of the core product or the margin of the attach product is greater than 50 percent.

Consider the case of a high-margin attach product bundled with a low-margin core product. Hewlett-Packard has collaborated with VMware and Microsoft to develop Smart Bundles, which integrate servers, storage, monitoring software, and virtualization software into infrastructure solutions for businesses. These bundles simplify the virtualization of the data center for customers and help promote the adoption of advanced, high-margin software for vendors.

Even if a company were to discount this kind of “high low” bundle by 25 to 30 percent, enough to spur adoption, it could still make significant incremental margins on the attach product without eroding core product sales. But think about what happens when the margins are much lower on the attach product than on the core product. For example, what if a software company were to attach a low-margin product like basic storage to a high-margin core product like enterprise software? If it discounted the bundle enough to spur adoption, it might not only wipe away the profit on the attach product but also erode the significant profit it was previously earning on the core product. (See Exhibit 2.)

Ensure that the value of the attach product is high enough compared with the core product. When the price of an attach product is small—15 to 20 percent of the core product’s value, for instance—consumers tend to view that part of the bundle as essentially a promotional gift or freebie. The attach product does not gain the customer’s commitment, so its penetration tends not to increase. This is particularly the case in the business-to-business space. Once a large discount has been negotiated, the customer is essentially getting the attach product for free. What looks like a freebie in the business-to-consumer market becomes a genuine freebie in the business-to-business market.

Enterprise software provides a good example. As these software companies have moved to the cloud, many have struggled with bundling lower-value cloud services with higher-value software. Discounts vary significantly, and bundling cloud-based storage with software risks wiping out the value of the offer. Cloud services are worth a lot less than the discount, so a customer that bargains for a 1 percent better price can easily receive a discount that exceeds the value of the attach product. In this case, cloud services are not an incentive, they’re a handout. A good rule of thumb is to make sure that the value of the attach product is one and a half times greater than the difference between the highest and lowest discount divided by two (this is known as the discount variance).

A potential bundle that does not meet these four criteria is a risky proposition. In the vast majority of cases, however, a company can meet all four and drive profitable growth with its bundles. By following these simple rules, TMT companies can avoid the most common pitfalls and make the most of a valuable pricing strategy for increasing market share.