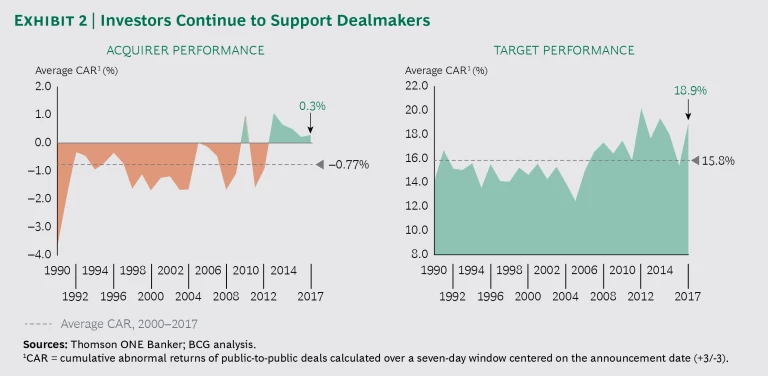

While M&A deal value continued to decline last year, falling 10% from 2016 and 34% from 2015, shareholder resistance to dealmaking was certainly not the reason. BCG analysis indicates that 2017 was the fifth year in a row that investors rewarded dealmaking, driving positive returns for acquirers. That’s a major departure from the historical pattern.

This steady investor support, along with still-cheap funding and slow organic growth, would seem like a good incentive for global dealmaking in 2018. And, in fact, monthly M&A deal value in January was the highest it has been since 2000. Even so, an array of factors—high valuations, changing regulations, rising protectionism, geopolitical worries, and the sudden volatility in the stock market—have some dealmakers worrying that the good times are near an end.

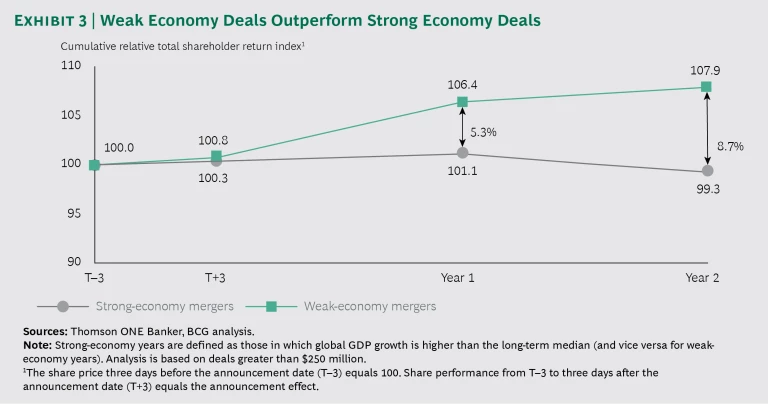

Some of those fears might be allayed by looking at a BCG analysis showing that deals executed during economic downturns outperform those done in a strong economy. Whenever the next downturn arrives, companies with the most robust M&A capabilities will have an excellent opportunity to set themselves apart from the competition.

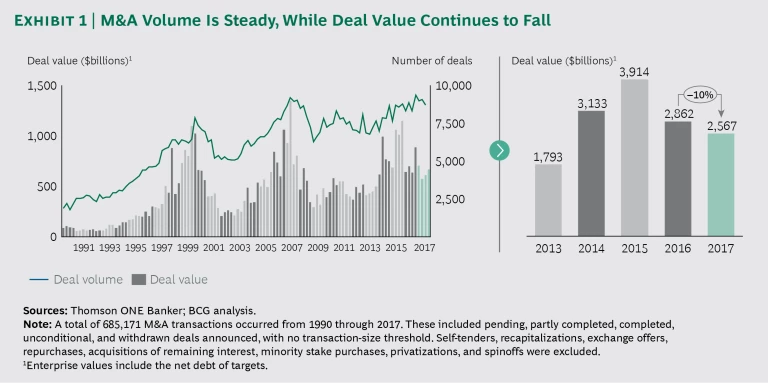

A Decline in Megadeals Leads M&A Value Downward

Dealmaking was a bit of a mixed bag in 2017. As noted, global M&A value declined for the second year in a row. Part of the reason was the decline in megadeals of $10 billion or greater, which dropped more than 50% from 2015. While very large deals declined, however, the total number of deals was steady. About 35,000 deals were announced in 2017, in line with 2016 and still above the five-year average. (See Exhibit 1.)

M&A value declined across all sectors with two exceptions: the consumer sector, which jumped 38%, supported by deals such as British American Tobacco’s acquisition of Reynolds American for $49 billion and Amazon’s $14 billion purchase of Whole Foods; and the financial services and real estate sector, which increased 12%. Regionally, South and Central America and Europe, along with Africa and the Middle East, showed growth in deal value. North America and Asia saw deal values decline.

This decline in deal value is somewhat puzzling given the factors in place that would normally foster M&A deals, not to mention the substantial amount of dry powder still available to private equity. The most likely cause of the slowdown is an imbalance in supply and demand. Appealing large-scale targets have become scarce and acquisition multiples have risen to historical highs. The median transaction multiple in 2017 was 14.2 times EBITDA, the highest since 1990 and up from 13.1 times EBITDA in 2016. In response, acquirers reduced the average takeover premiums from 32.4% in 2016 to 24.8% in 2017.

Despite record-high valuations, investors are generally more supportive of M&A deals than in the past. Until recently, investor reaction to an announced deal was fairly predictable: the target’s share price jumped to somewhere near the bid price, while the acquirer’s stock fell on concerns of earnings dilution, poor fit, excessive diversification, or some other factor. For the last five years, however, the cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) of both targets and acquirers have been positive, indicating that investors are placing their bets on dealmakers. (See Exhibit 2.)

Bad Times Are Good Times for Acquisitions

At the start of 2018, the Bloomberg consensus estimate for global GDP growth was around 3.7% for the year, the highest since 2011 but only slightly above 2017’s and the long-term average. But even if the global economy were to suddenly take a turn for the worse, dealmakers would be wise to press on, and perhaps even redouble their efforts.

We’ve drawn this conclusion after digging into the unique dataset underlying our 2017 M&A report (The Technology Takeover, BCG report, September 2017). We looked at global transactions of more than $250 million from 1985 through 2014 and separated them into weak-economy and strong-economy groups on the basis of the macroeconomic environment on the date the deals were announced. What we found is that weak-economy deals performed better than strong-economy deals.

Even if the global economy were to take a turn for the worse, dealmakers would be wise to press on—perhaps even redouble their efforts.

As a group, strong-economy deals destroyed value for the buyer over a two-year period, while the weak-economy mergers helped improve total shareholder return. The total shareholder return of the weak-economy mergers was almost 9% greater than the strong-economy mergers and generated positive returns on average. (See Exhibit 3.) Only 43% of the strong-economy transactions created value over a two-year period, compared with almost 51% of the weak-economy deals.

There is some debate over what’s driving this divergence in performance. One argument is that buyers in good economic times tend to overpay and are later punished by shareholders for not meeting high expectations for benefits such as cost savings and revenue synergies. At the same time, deals executed in less frothy markets have lower valuations and more conservative goals, which make their chance for success greater.

These factors almost certainly play a role in the performance of some deals. But we contend that a more significant factor is at work. During heady economic times, many companies without much experience or discipline will pursue acquisitions resulting in overall poor outcomes. But in challenging economic times only companies with strong M&A capabilities as part of their ongoing growth strategy have the courage to pursue deals. We believe these firms will continue to have the support of their shareholders no matter what 2018 holds.