International building materials and construction players have heard the rumblings around China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative, and they have seen the inroads that Chinese companies in the industry are making into emerging markets. Many wonder what OBOR means for their business, for global pricing, and for trade.

While a number of articles have addressed China’s growth ambitions in general (see, for example,“Dueling with Dragons 2.0: The Next Phase of Global Corporate Competition,” June 24, 2015), none so far has offered a comprehensive perspective. Here, we look at China’s planned trillion-dollar network of investments along the “new Silk Road,” its overall investment proposition, and the market impact, and we offer some recommendations for the building industry based on the global implications of OBOR.

One Belt, One Road: A Network of Investments

During the Han Dynasty, the Silk Road network of maritime and overland trade routes served as a rudimentary and often grueling link between countries, from China and India to the Mediterranean Sea. On these ancient routes, used as early as 130 BC, goods such as silk, spices, gunpowder, and perfumes traveled westward, while gold, silver, horses, textiles, and other items moved eastward—resulting in profound changes to the development of the modern world.

Today, China has revived the ancient Silk Road network of trade routes with its OBOR initiative, announced in 2013 and intended to deepen the country’s economic ties with Asia, Africa, and Europe. This modern Silk Road, while based primarily on foreign investment rather than trade goods, is also destined to have a profound impact. China’s total foreign direct investment (FDI) into OBOR is expected to exceed the annual gross domestic product (GDP) of Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam combined, according to the World Bank, climbing to $1 trillion over the next decade. Contrast that with China’s typical annual FDI in the past, which has hovered around $50 billion to $80 billion globally, according to the FDI Market Database.

China has a number of important reasons for expanding its FDI in the developing world, all of which have led to powerful internal support for the OBOR initiative, including government backing for foreign infrastructure projects and simplified investment record and approval procedures. Its increasing FDI in emerging markets allows China to reinvest its high foreign exchange reserves. In addition, growing FDI compensates for slowing internal growth, while diversifying the country’s production base. The country is also working to ameliorate its overcapacities in industries such as cement by shipping overage to its OBOR projects.

Broadly speaking, China’s engagement abroad allows it to pursue four objectives (see also Exhibit 1):

- Asserting Geopolitical Influence. China is reaching out with its OBOR initiative in part to expand the country’s geopolitical influence. The Chinese shipping company COSCO, for example, now owns a controlling stake in the Greek port of Piraeus, a vital shipping hub linking the Asian continent and the Mediterranean.

- Gaining Geo-economic Power. China recognizes the opportunity to broaden its global economic power by developing ties to such international markets as Ethiopia, in the textile sector; Egypt, in the Suez channel zone—an important trade gateway to Europe; and the fast-growing markets of Southeast Asia.

- Increasing Access to Raw Materials. Accessing raw materials has probably been the biggest reason for Chinese overseas investment in the past, as China has sought access to natural resources in Africa and Latin America that would fuel its domestic growth. More recent examples include oil imported from Brazil and coal from North Korea, although tapping raw materials has become less important as China’s domestic growth has slowed.

- Accessing Innovative Technology. Obtaining access to new technology has led China to acquire a number of tech companies abroad. These companies, typically Western, supply Chinese businesses with know-how and R&D.

Note that Chinese investment activities have not been as strong at the Western end of the Silk Road as at the Eastern end, because EU laws forbid financing arrangements that include the awarding of project contracts. As a result, projects in Romania, for example, tend to proceed more slowly than projects in countries such as Egypt.

China’s Investment Proposition

OBOR initiatives follow the pattern of most large infrastructure investments. There’s an upfront engineering and design phase, then financing, followed by the project construction, which requires large volumes of building materials. Upon completion, the infrastructure must be operated and maintained.

We can probably attribute China’s successful investment performance to date to its ability to offer support throughout a project’s life cycle, from design to operation, with varying degrees of involvement of Chinese companies along the spectrum. (See Exhibit 2.)

Specifically, China supports projects through five stages:

- Step I: Design and Engineering. Chinese companies frequently conduct the design and engineering work for their projects in cooperation with international partners; alternatively, they acquire local design and engineering businesses, helping develop their own knowledge and capacity in the countries in which they have large infrastructure projects.

- Step II: Financing. At the root of every successful OBOR project is financing. International investors typically perceive projects in emerging economies as risky, demanding return rates of 25% to 40%. In contrast, Chinese companies have fewer such reservations, usually conducting international projects with return rates of around 10%, despite the higher likelihood of losses from such projects. We therefore see Chinese specialized agencies such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Silk Road Fund, multilateral institutions such as the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, and Chinese banks seeking to fund projects in those developing countries with which China seeks a stronger relationship.

- Step III: Construction. Chinese banks typically require that Chinese construction companies be awarded the relevant projects as a precondition to financing, ensuring that the latter—primarily state-owned—businesses act as the main contractors. Not surprisingly, Chinese construction firms already generate 20% of their revenues abroad, a share that is growing steadily.

- Step IV: Building Materials. Chinese companies often import the building materials required for each project from China, such as cement, rather than using local materials, as a result of the current production overcapacity in China.

- Step V: Operations and Maintenance. Interestingly, operations and maintenance are typically handed back to local institutions once a project is built. However, we have seen recent efforts to maintain control of certain facilities, and in a few years we believe that China will also be strongly involved in executing its infrastructure projects.

While some governments have resisted Chinese inroads into their countries’ economies, many developing countries along the OBOR corridor seem grateful for Chinese engagement and the accompanying monetary inflow; infrastructure and transportation improvements; increases in production and job opportunities; and often, reduced costs. In the Greek port of Piraeus, for example, operational costs per shipping container have shrunk from €36 to €15 and cargo volumes have increased substantially since COSCO took on the port’s management. In fact, COSCO alone brings about 400,000 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units) of cargo to Piraeus each year, or around 30% of the port’s peak handling capacity.

China also acts neutrally regarding the internal affairs of the countries in which it invests, an approach that allows a smoother implementation for OBOR projects. Moreover, Chinese companies offer lower labor and materials costs than other international operators and can cite in-depth examples of their experience in railroads and other infrastructure. One reason for the latter is that China has undergone a similar journey over the past four decades to that of many developing countries. It, too, has faced challenges such as environmental problems, inequitable wealth distribution, and strife among its various ethnic and religious groups.

The Impact on the Construction and Building Materials Industry

Countries sitting in the new Silk Road corridors are seeing a strong impact from OBOR on both international and local businesses, with Chinese investments becoming increasingly diverse. While around 70% of OBOR projects were concentrated in the infrastructure and energy sectors from 2013 to 2016, that proportion has decreased to about 40% today, with investments in manufacturing, service industries, and technological projects now making up the remaining 60%. These investments are having a substantial impact in three areas: heavy building materials such as cement, light materials such as windows, and the overall construction market.

The Heavy Side. Heavy building materials, including cement, have been most strongly affected, with prices falling because of Chinese imports, lower-cost local production, and newly built capacity. Chinese cement producers appreciate OBOR as an opportunity to reduce their overcapacity, which increased from 23% in 2010 to 42% in 2017, according to the Global Cement Report.

Many of China’s exports today are headed to East Africa. Cement and clinker, cement’s core component, are frequently shipped there on bulk freighters that have delivered coal from Africa to China and would otherwise return empty. With its low production costs, China can more than offset the cost disadvantage resulting from shipping rather than producing locally. Consequently, local supply and demand in East Africa are now out of balance, and cement prices have fallen by 50% over the past few years.

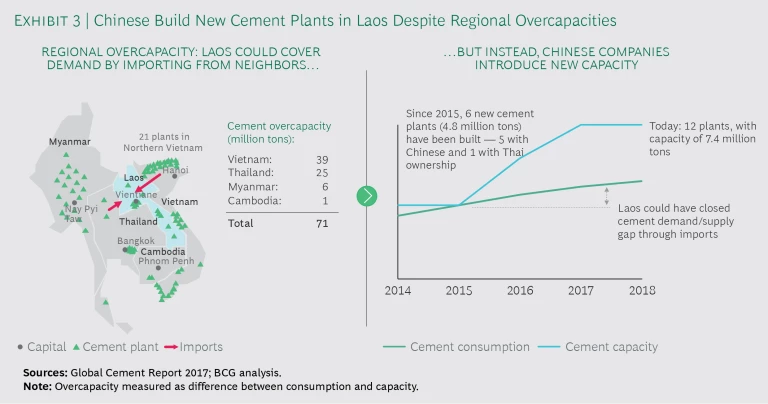

In the Mekong region of Southeast Asia, overcapacities totaling around 70 metric tons per annum have emerged. For example, Laos is a small cement consumer that could easily close the narrow gap between its demand and supply through imports. North Vietnam alone has 21 cement plants that could supply materials across the border to Laos. Nonetheless, six new cement plants have been built in Laos since 2015, when the country began a railway project funded and constructed by Chinese businesses. Of these six plants, five are Chinese-owned and one is Thai-owned. (See Exhibit 3.)

The Light Side. Demand is growing for light building materials such as roofs, windows, insulation, plaster board, and flooring, triggered by further expansion in the residential and industrial segments in the prospering OBOR regions. While the impact on the light-side market is not completely clear, we see Chinese companies moving into this arena to meet demand, typically in partnership with local players. For example, China National Building Material Company has opened factories in the UK to supply building materials to nearby markets. The company is also partnering with three European companies to develop real estate, generate renewable energy, and provide technology, respectively, according to UK Construction Week 2018.

The Construction Market. International and local construction players are experiencing a relatively low level of market disruption, as the growth of Chinese-backed infrastructure projects has sparked new construction demand for all participants. Moreover, Chinese firms often ask local and international firms to partner with them on construction projects, particularly when those firms offer specialized technology or regulatory knowledge, providing a model that allows other players to participate in the overall growth.

Four Recommendations for the Global Building Industry

As international firms seek to understand and respond to China’s OBOR initiative, we recommend they take four steps: consider partnerships with Chinese players, conduct a strategic review of markets affected by the initiative, rebalance their business mix toward light-side construction materials, and continue to innovate.

Seek partnerships. While competition increases in markets affected by OBOR, the investments themselves create new opportunities. Chinese players may offer strong execution capabilities, often along with low costs and good experience, but international players can contribute their own expertise in areas such as technology, best-practice safety standards, and national regulatory approaches. Government backing helps to promote these partnerships: Singapore, for instance, announced it would establish an infrastructure investment office in early 2018 that would bring together local and international companies to develop and execute infrastructure projects in the region.

Review the strategy. As they seek out new partnerships, companies should also look closely at the effect of OBOR investments on each of their markets. If beneficial partnerships are impractical, they should determine where they need to move to protect their investments—and where they need to exit.

Refocus the business mix. Given that OBOR investments focus on large infrastructure projects, companies facing new competition for these projects should increase their own focus on local construction demand, such as residential work.

Keep innovating. Many companies’ procurement departments are more focused today on total cost of ownership (TCO) than on market price—looking at the cost not only of acquiring the product, but of using it throughout its lifetime. International players should therefore work to keep a competitive edge, innovating and bringing value to clients through superior systems, solutions, and services. Key areas for TCO innovation include technology, product quality, and market and customer excellence.

Even beyond the tremendous consequences for the construction and building materials industry along the new Silk Road, we believe new OBOR-generated pathways will have a powerful impact. Benefits include decreased transportation time, as newly built railways offer faster alternatives to sea freight; new participation in international trade routes by relatively remote regions such as Ethiopia and Kazakhstan, thus increasing their prosperity; and the continued expansion of the OBOR network, as Chinese manufacturers target additional low-cost regions as attractive investments.