In the busy realm of software M&A, perception isn’t always reality. For industry players, deals can be a crucial way to boost innovation, the talent pool, and growth. Yet while participants may consider their integration a success, a closer look often reveals a more complicated—and less triumphant—story. Post-merger revenue and value creation don’t always rise to expected levels. Key opportunities and synergies are often slow to develop. Indeed, companies are sometimes unsure if the opportunities they planned to pursue even materialized.

If mergers are truly to deliver value, software companies need to plan and align across four key areas: product portfolio, go-to-market synergy strategy (with a particular focus on cross-selling), operating and organizational models, and a go-forward culture. And they need to do so upfront and quickly, all while having clear visibility into the integration and sending the right messages to employees, customers, and shareholders.

The key is to take a focused and agile approach to PMIs. The focus comes by zeroing in on the value drivers of an integration and defining—and continually measuring—KPIs. The agility comes from applying the same agile methodologies that companies have embraced in their development processes. The idea: If software companies can create their products faster and with better results, why can’t they do the same for their PMIs?

Mission Not Quite Accomplished

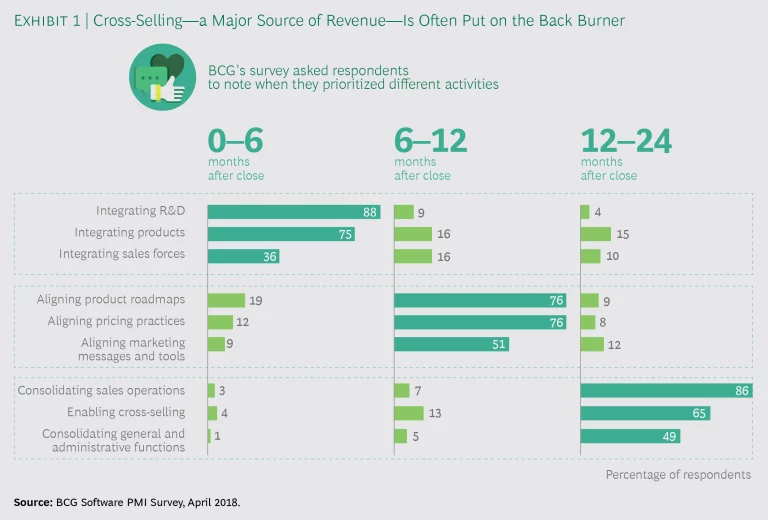

The disconnect between how companies view the success of their PMI and what they actually achieve can be startling. In a 2018 survey by BCG, 96% of participants—covering acquiring and target companies in 15 software deals—rated their merger as very or mostly successful. Yet that same survey uncovered some troubling signs. Companies frequently experienced problems with talent retention during the integration process. And they often didn’t take up cross-selling—one of the most crucial, and proven, ways to spark revenue synergies—until long after closing. (See Exhibit 1.)

Then there are the hard numbers. A BCG analysis of 32 software deals from 2013 through 2017 reveals that one year after closing, 59% of the acquirers had experienced a decline in their operating margin and nearly two-thirds—65%—had lower year-over-year revenue

Bumps in the Road to Synergies

Software M&As have seen notable spikes in recent years. In 2013, 8 deals valued in excess of $500 million were publicly reported. A year later, 17 such transactions took place—with total value increasing dramatically, from $12 billion to $46 billion. Since then, M&As have ebbed and flowed but have consistently remained above 2013 levels, peaking at 23 deals valued at a total $77 billion in 2016.

Given the significant cash that many software players have on hand and the big benefits that a merger can potentially bring, most experts anticipate more deals to come. For many companies, a PMI is not a one-shot event. They need to master the process. Indeed, we’ve found that companies that learn from their experiences and build expertise over time have more success driving value in integrations. (See “Lessons from Successful Serial Acquirers,” BCG Perspectives, October 2014.)

Most software companies are not yet there. BCG’s survey (whose 91 participants were all involved in a software deal), along with our analysis of recent software mergers and select follow-up interviews with survey respondents, revealed a number of trouble spots. These pitfalls lurk in every software integration and too often turn into problems:

- A Failure to Set—and Track—the Right Goals for Value Creation. Most software integrations still have an old-school, consolidation-first bias. On the cost side, specific goals are set and tracked, and accountabilities established for senior executives. But that same rigor is rarely seen on the revenue side. Instead of setting ambitious objectives—and quickly taking steps, like prioritizing cross-selling, to meet them—companies tend to establish a general revenue target, or none at all. And they usually have little, if any, senior-level visibility into the opportunities that are pursued. As a result, companies lose the ability to see what is working and to hold executives and managers accountable for the results.

- Passing Product Decisions to the Future. A failure to make explicit product decisions early on—an all-too-common occurrence in software PMIs—can lead to years of indecision and inefficiency. A decade after merging, many companies still have overlapping products—but don’t have the will to make hard choices.

- A Revenue Dip After Closing due to Uncertainty About Products. In our analysis of software deals, we found that one-third of the merged companies experienced a revenue drop greater than 10% in the three months after closing. A likely contributor: customer uncertainty about a product’s future. Software purchases and renewals are often discretionary, and customers may put aside their checkbook until the air clears.

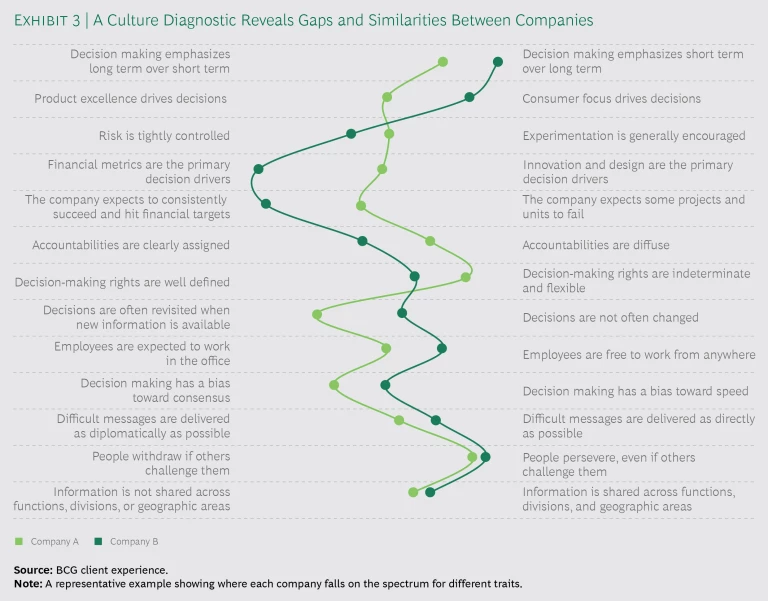

- Differences in Culture. Corporate cultures rarely mix, and without alignment, employees cling to their preexisting ways of working—something that can cause conflict and dampen performance and teamwork. Nearly half of the survey respondents—42%—noted that the cultures of the acquiring and target companies were completely different. And the biggest differences were along some of the most crucial dimensions: risk taking, experimentation, and the decision-making process.

- Talent Attrition. Human talent is the core asset of software companies, and in any merger, developers are a serious flight risk. They might find it very difficult to work in an environment that is less agile than what they are accustomed to, and rather than adjusting to a new approach, they might simply take their skills elsewhere (with the most talented the most apt to leave). In the survey, just 58% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that agile practices had improved in the combined company. It’s likely no coincidence that only 62% agreed or strongly agreed that attrition was at normal levels during the integration process. Meanwhile, the seeds of uncertainty—sown by a lack of transparency and communication about the merger—can grow into suspicion and doubt and spur exits.

- Insufficient Engagement—and Rigor—from the Top. Surprisingly, only 19% of respondents strongly agreed that top management was visibly involved and engaged in the integration. Without a fully supported—and closely tracked—integration plan, companies are likely to face delays and glitches in its execution. Indeed, only 60% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that no major hiccups occurred during the integration, such as operational disruptions and slower-than-usual decision making.

A Focus on the Value Drivers

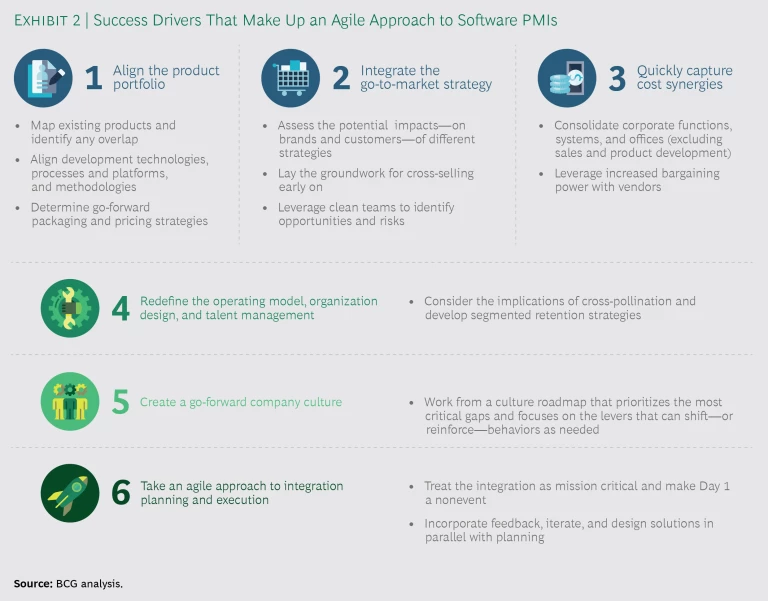

So how can software companies avoid the PMI pitfalls? Our approach is to focus—and focus early—on the key drivers of integration success. (See Exhibit 2.) Crucially, this approach applies the same agile principles that have transformed software development: cross-functional teams, iterative sprints, frequent testing and learning, and leaders who are empowered to make decisions quickly—and are accountable for the results.

What follows is a look at each success driver and the strategies that enable companies to extract maximum value, in minimal time, from their mergers.

Aligning the Product Portfolio. A carefully crafted product portfolio can avoid confusion and spark the revenue synergies that are almost always a chief goal of software mergers. It’s one thing to avoid developing and selling competing products; the real value comes from leveraging the best of the acquirer and the target. In one integration we supported, the combined company took complementary offerings for CFOs and created a single end-to-end solution—a value proposition that neither the acquirer nor the target could offer before the merger. The key was setting everything in motion before the deal close, so that on Day 1 the company could communicate a clear message that reassured customers, stabilized the market, and helped it avoid the dreaded postclose revenue dip.

A carefully crafted product portfolio can avoid confusion and spark the revenue synergies that are almost always a chief goal of M&As.

Optimizing a portfolio isn’t always straightforward, but certain practices can ease the way. The first step is to have a deep understanding of the existing portfolios. What products and features does each company offer? What strategic markets and business processes does each product cover? Who are the target customers? The actual customers? By knowing this information, business leaders can map existing products and identify any overlap.

The next step is to do something about that overlap. This means determining which product has the best fit with the strategic markets. It also means that when companies mark a product for sunsetting, they define the details and timing for a migration plan.

If no overlap exists, the question is whether to offer the product going forward. Here, too, a deep understanding of the portfolio can help in the decision making, spotlighting products that align—and don’t align—with the merged company’s business priorities.

Keep in mind that every decision will have a unique and potentially significant impact on the customer. What might sunsetting a product mean for customer retention? What migration path will resonate best with key clients? To make the savviest decisions—and minimize risk—the two companies need to collaborate closely to understand and address potential customer concerns.

It’s also important to align development technologies, governance mechanisms, and methodologies. Common processes and platforms, along with policies that encourage the sharing and reuse of IP, can drive efficiencies. They can also fuel revenue synergies—and growth—in the years after the integration. Meanwhile, a uniform approach to agile can spur teamwork and speed the pace of innovation.

Integrating the Go-to-Market Strategy. As they develop their product roadmap, the companies should also create a go-to-market approach for the combined organization. This means assessing the potential impacts—on brands and customers—of different strategies. Consider one merger that occurred in the security space. The combined executive team understood that the two companies offered nearly identical products—so much so that it made a lot of sense to sell a single consolidated product going forward. But a brand analysis revealed an important caveat: don’t sell it under one label. Each of the existing brands generated such strong search results that it would be more effective to sell the product under the two existing labels, at least in the medium term.

Although the best go-to-market strategies minimize disruption to customers, they also help companies seize new opportunities to generate revenue. Cross-selling, for instance, can be a major value driver. Yet only 4% of survey respondents said that their companies prioritized cross-selling within 6 months of the deal’s close. Just 13% said that they prioritized it 6 to 12 months after close.

The best go-to-market approaches minimize disruption to customers but also help companies seize new opportunities to generate revenue.

Companies need to lay the groundwork for cross-selling early on, and one of the best ways to do this is by using a clean team. Legally separate from the acquirer and target, a clean team can analyze data that the two companies cannot share before the deal closes, such as sensitive information about products, pricing, customers, and share of wallet. It can identify logical places to cross-sell or upsell and can quantify the financial benefits—so that companies can start creating value as soon as the deal closes.

The benefits of using clean teams don’t end there. These teams can also identify, and plan to mitigate, risks—in the case of overlapping customers and products, for instance. They can accelerate the creation of a unified sales structure, where roles and account ownership are defined before the deal closes. This is particularly important when it comes to overlapping customers. So on Day 1, the combined sales team can identify one clear account owner (and, as needed, product specialists) to pursue new revenue opportunities.

Companies also need to create the right sales support system and include essential checklist items such as training, collateral marketing material, Day 1 account plans, incentives, and lead generation and tracking. Before the close of an acquisition, one major software player trained each company’s sales force on the other’s products and defined the account coverage model as well as an incentive structure that encouraged cross-selling. Specifically, sales representatives from both companies would be compensated for cross-sell transactions—irrespective of who originated the sale.

As companies align product roadmaps and go-to-market strategies, they can zero in on synergies and set revenue targets that are ambitious yet realistic. This in turn enables senior-level accountability. By tracking targets, companies know when they are falling behind in their goals. They gain visibility that lets them address problems and create a feedback loop in which they are continually learning from results and applying the lessons.

Quickly Capturing Cost Synergies. While often not the primary rationale for software M&A activity, cost reduction is an important—and in many cases, highly achievable—objective. Savings can come via numerous routes: common development platforms, IP reuse, increased bargaining power with vendors, and consolidated functions and systems within finance, human resources, IT, and other departments.

But when it comes to savings, companies need to see the big picture. Many of the decisions made during an integration—choosing the target operating model, the activities to centralize or outsource, the number of people managers will oversee, and so on—can affect costs. And they may also have an impact on employee morale, productivity, and customers. For example, aligning the technical stack—consolidating systems and promoting common and shared technologies—can bring significant savings. But IT is a critical enabler of business continuity and revenue synergies like cross-selling. So companies need to be careful that the savings they’re realizing today aren’t outweighed by the value they’re missing tomorrow. When choosing the go-forward IT systems, a good rule of thumb is to be pragmatic and generally avoid making dramatic changes.

Companies need to be careful that the savings they’re realizing today aren’t outweighed by the value they’re missing tomorrow.

In software integrations—where there is a big risk of talent attrition—it’s critical to evaluate changes in terms of employee experience and morale and determine if the measures will be seen as positive and not detrimental to growth opportunities. Generally, back-office changes that don’t affect customers, sales, or developers are more feasible.

Redefining the Operating Model, Organization Design, and Talent Management. One key trait of successful serial acquirers is that the senior-leadership team is deeply involved in the M&A process. Executives develop a clear rationale for a deal and communicate it to the organization. In our experience, success is fostered when leaders from both sides come together early in the integration process and align on the vision and mission. This gives companies a running start on identifying opportunities. It helps ensure that decisions and actions support the goals of the integration. And it lets employees, customers, and suppliers know what lies ahead.

One of the most important early decisions is what the go-forward operating model will look like. The idea is to create a model that reflects the rationale for the deal. A deep understanding of vision, mission, and opportunities can guide the way. So, too, can the answers to specific questions. To what extent will the target company stay separate or be integrated with the acquirer? What will be the new business units and product lines? What resources will be dedicated to specific business units? What resources will be shared?

Once companies have determined the operating model, they can then use it to inform their decisions regarding organization design and roles, beginning with the new entity’s senior-executive team. When filling roles at this level, two practices are key:

- Consider the strengths of the respective legacy companies. For example, if a major reason for acquiring a company is to access a new market, it makes sense to retain most of the existing talent for that market.

- Think about the implications of cross-pollination—or lack thereof. If the members of the new executive team all come from the acquiring company, employees may expect this approach to trickle down. As a result, critical talent in the acquired company might leave for other pastures. Aside from functions where one company has specific expertise, it’s generally a good idea to cross-pollinate the executive level and the layers below it.

For software companies, talent is everything. So retention should be a focal point early in the integration. We recommend segmenting talent into three categories: staff who are critical for the long term (such as software developers); those who are required for a specific period of time (such as IT integrators); and all others needed for business continuity. Grouping talent in this way is very useful when creating retention strategies. For example, financial incentives may resonate with short-term employees, while nonfinancial inducements—such as new roles and responsibilities, clear recognition for work, and personal outreach from executives—are often more influential with long-term talent.

Transparency is another must in dealing with employees. It gives them clarity during a PMI, setting expectations and reducing anxiety and rumors. (People frequently fill a vacuum with negative assumptions that affect morale.) Some good practices include dedicating staff to PMI communications; providing consistent and credible information on processes, vision, and goals; and giving frequent updates as decisions are being made. Companies should also seek employee feedback, on an ongoing basis; for example, through monthly “pulse check” surveys and informal communications. This is crucial for quickly identifying—and mitigating—retention risks.

Creating a Go-Forward Company Culture. The blending of cultures is both a cornerstone and a key challenge of any merger. While it typically takes at least two years to transition fully to a new culture, planning should start early in the integration process. Launching the new culture right at the deal’s closing is a great way to signal that the two companies really will operate as one.

The blending of company cultures is both a cornerstone and a key challenge of any merger.

A three-faceted approach can help companies create the new culture quickly and successfully.

The first step is to zero in on the cultural differences and similarities between the acquirer and target. This can be done through a leadership survey—targeting the top three or four management layers in each organization—along with executive interviews. The goal is to draw a clear picture of how the companies compare along a number of key dimensions. (See Exhibit 3.) While differences will show gaps between cultures, similarities can help identify where, and how, bridges might be built. For example, both companies may be very focused on winning in the marketplace but take different approaches to get there. (One company might focus on breakthrough technologies; the other on a superior response to customer needs.) This common winning mentality can be a core part of the new culture—something that resonates with employees from both companies.

Using this culture diagnostic as a starting point, the next step is to define the new culture. Even when two companies have very different cultures, we’ve seen productive alignment toward a well-defined target. It becomes a goal that the new organization can rally around. Workshops are a great venue for bringing together the CEO and the new executive team to articulate the combined company’s purpose, values, and behaviors. Savvy companies schedule multiple workshops so that participants can incorporate feedback and iterate on the proposed culture.

This kind of iterative collaboration helps leaders from both companies make hard choices and tradeoffs before the deal closes. They can decide on the processes for approving new products and for attracting and retaining talent (determining incentive structures and promotion criteria, for example). They can zero in on the level of experimentation allowed, how decisions will be made, and financial discipline (including the process for financial planning, the KPIs to track, and who will be involved in decision making).

Finally, companies should create a culture roadmap that prioritizes the most critical gaps and focuses on the levers that can shift—or reinforce—behaviors. (See “Breaking the Culture Barrier in Postmerger Integrations,” BCG report, January 2016.) A good roadmap specifies how leadership can demonstrate and reinforce new behaviors. It highlights relevant communications and engagement actions. And it details changes to roles, processes, and policies (such as incentive programs, budgeting and planning processes, and the code of conduct) that will have a significant impact on behaviors.

Taking an Agile Approach to Integration Planning and Execution. In our survey, only 61% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their integration was managed as a critical project outside business as usual, with dedicated resources. That’s far too low. Treating an integration as mission critical boosts the odds that Day 1 will be a nonevent.

A crucial similarity exists between innovation and integration: both require fast, iterative processes—fueled by feedback—that enable quick decision making.

But what, exactly, does it mean to treat an integration as a top-priority project? For us, it means applying the same rigor and commitment that software companies apply to innovation. In fact, a crucial similarity exists between innovation and integration: both require fast, iterative processes—fueled by feedback—that enable quick decision making. Or to put it another way: an integration, like innovation, can benefit greatly from an agile approach.

We’ve found that companies that do agile integration well share certain traits. They outline—right at the start—the overall timeline and goals for the integration, focusing tightly on the key sources of value. They break down the integration into discrete problems, such as portfolio alignment, and create cross-functional teams to tackle them (though for some types of work—like finance integration—teams still come from a specific function). They provide clear financial and nonfinancial objectives and empower team leaders to make quick recommendations using available data. The agile approach both streamlines and improves the integration process: teams incorporate feedback, iterate, and design solutions in parallel with planning.

Clear governance is another important box to check. In our experience, the best model is one where team leaders report to a central integration management office overseen by a pair of senior integration leaders, one from each company. These are usually up-and-coming senior executives, well respected within their organization. The integration leaders are accountable for the success of the PMI, and they report, in turn, to a steering committee. In this model, a strong steering committee is crucial. It must be empowered to make the critical decisions related to the integration in a timely manner.

For software companies, M&A has become an important route to growth. Yet many deals do not realize their potential—or at least not without delays, complications, and even disappointments. It doesn’t have to be that way. Companies have formidable levers at their disposal. It’s time to apply them and—with more deals coming—master them.

With a focused, agile approach to PMIs, software players can create significant value, with speed and efficiency. In other words, M&As can deliver on their promise—in full.