Over the past five years, the global retail sector has continued to deliver strong value creation, though it has most recently been overtaken by other sectors that have performed even better.

In 2014, as in past years, The Boston Consulting Group conducted an annual study of total shareholder return among 1,620 publicly traded companies in 26 industry sectors, of which 68 were in the retail

There’s a critical difference between the absolute TSR performance of individual sectors and their ranking relative to one another. In our 2013 Value Creators report, which looked at companies’ performance from 2008 through 2012, retail ranked first in value creation across all industry sectors, yet it had a much lower return—an average TSR gain of only 11 percent a year. This was because the starting point for that study was 2008 and included the steep drop in equities at the beginning of the financial crisis. In contrast, the 2014 study covered a period when most equity indices boomed, so while absolute value creation increased among retail companies, other industries posted even greater increases in TSR. (By comparison, the benchmark MSCI All Country World Index returned roughly 15 percent in TSR over the most recent five-year period studied.)

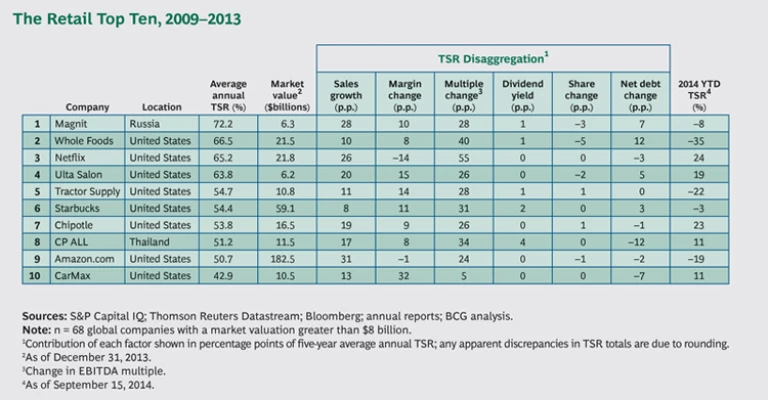

Among retailers, the top-performing value creator overall was Magnit, a Russian grocery chain. (See the exhibit for a breakdown of all the companies in the retail top ten.) Magnit operates approximately 8,000 convenience stores, 800 cosmetics stores, and 170 hypermarkets, along with a strong logistics division to support them all. It is the biggest retailer in Russia by revenue (with roughly $15 billion in sales) and one of the biggest employers, with about 230,000 employees.

The only other non-U.S. company in the top ten was CP ALL, a Thai company that operates convenience stores, supermarkets, and other grocery formats across Southeast Asia. Like Magnit, CP ALL has posted strong, profitable growth, and it has benefited from a consolidation strategy of rolling up small players in highly fragmented emerging markets.

The remaining eight companies are all based in the U.S. and include grocers (Whole Foods), restaurants (Chipotle and Starbucks), and automotive stores (CarMax); in addition, this group includes two pure-play online companies (Netflix and Amazon). Both Starbucks and Amazon were also among the top ten large-cap value creators across all industry sectors—not just retail—for the period 2009 through 2013.

Magnit and CP ALL are unique in that they were the only two repeat performers among the top ten (the remaining eight were new to the group). The companies that fell out of the top ten show how recent economic growth in the U.S. has shifted the deck within retail. Several of those companies were dollar store chains, or they had some other strong position in discount retail, which has been overtaken by other retail segments.

Notably, half of this year’s top ten retail companies posted negative TSR for much of 2014 (through mid-September). This could indicate a simple regression to the mean—the companies that soared recently are returning to Earth. But it highlights the dynamic nature of the retail environment. It is difficult to outperform the pack and even more difficult to sustain that performance over time.

The Drivers of TSR

A closer analysis of the factors that contributed to value creation in the retail sector shows some notable trends. The biggest TSR driver was an expansion in the valuation multiple, resulting from the strong belief among investors that despite a challenging environment for retailers globally, these ten companies have the right operating model in place to create value. Nine of the top ten retail companies posted multiple increases of 24 percentage points or more over the five years from 2009 through 2013. When equities perform well—as they have over the past several years—valuation multiples have an outsized influence on value creation.

The second biggest contributor to TSR was sales growth, followed by operating margins. (The other three components of TSR—changes to the dividend yield, net debt, and the number of shares outstanding—had relatively little impact.) The relationship between sales growth and margins is clear: companies must find growth, but not at the expense of profits. For example, Starbucks managed to post solid global growth during the period analyzed, but not at the expense of other factors. Sales growth contributed 8 percentage points to the company’s annual TSR from 2009 through 2013—the least of all the companies in the top ten. Yet its valuation-multiple expansion was among the highest, at 31 percentage points. Why? Starbucks has not chased growth for its own sake. It has opened new stores while closing down those that underperform, and the market has rewarded its discipline.

Another theme emerges from our analysis: two of the top ten—Amazon and Netflix—are Internet pure plays, and the remainder are predominantly in segments that have been slower to move online, such as groceries (Whole Foods), quick-serve restaurants (Chipotle), and do-it-yourself stores (Tractor Supply).

The two Internet pure plays are noteworthy in another way. Netflix and Amazon are the only two companies in the top ten to post contracting margins from 2009 through 2013: –14 percentage points of annual TSR for Netflix and –1 percentage point for Amazon. This indicates that some online players are still in the land-grab stage of their development. However, the recent, well-documented struggles of Amazon may indicate that if growth comes in segments that stray too far from the core business, it can quickly destroy value.

Insights for Retail Players

The value creation performance of Amazon and Netflix offers several insights for management teams. First, retailers must accelerate efforts to counter the online threat to their business. Most of the companies in the top ten operate in segments that are difficult for Amazon to attack, but their competitors will keep coming. Creating omnichannel experiences that seamlessly combine digital and real-world interactions will be key.

The second insight is that in the near term, valuation multiples—which made the largest contribution to value creation over the past five years—are critical. For retail management teams, the message is clear. Companies need to take steps to address their multiple through an integrated approach that aligns their business, financial, and investor strategies.

Consistent performance against a well-articulated investment thesis is critical. Wall Street must have confidence in management and its ability to execute against objectives. Moreover, companies must identify the right investor base, that is, portfolio managers whose objectives—growth versus value versus “growth at a reasonable price”—align with their own. And communication with these investors must be clear and consistent, particularly regarding changes in strategy.

The third insight is the importance of transformation. The amount of churn in the retail industry overall—and in the rankings among the companies in the top ten—is extremely high. As noted above, eight of the ten companies are new to the list this year. In addition, only the restaurant segment has more than one representative in the top ten, illustrating that while segment matters, what matters more are the strategic choices that differentiate winners and losers. Earlier BCG research has quantified this effect across all industries. In 1950, the market leader in a given industry was also the profitability leader 35 percent of the time. Today, that correlation has fallen to just 7 percent. During the same period, the volatility of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) margins has jumped nearly fivefold. (See Transformation: The Imperative to Change, BCG report, November 2014.)

This trend is only likely to gather momentum in the foreseeable future, driven by emerging technologies and changes in consumer behavior. Winning operating models become obsolete more rapidly than in the past, as newer and more nimble companies rise up to overtake dominant players.

The right response for retail executives is not to seek some theoretically perfect operating model or value proposition. Even if such a thing existed, it would not last. Rather, they need to expect change—and expect to change accordingly, through transformation efforts that rewire the business in response to evolving market conditions. Conventional wisdom holds that transformations are only for failing companies—those that need to make a last-ditch effort to turn themselves around. This is not longer true; among BCG clients that have launched transformation efforts, approximately one in four has done so from a position of strength (that is, as the market leader). Moreover, transformations are not a once-and-done endeavor. Instead, companies must seek to continually reinvent themselves through new store formats, multichannel opportunities, stronger execution, and better ways to serve the customer.

Fundamentally, retail remains a highly dynamic environment, yet our TSR analysis shows that there are clear opportunities for companies that can craft the right strategic response.