This is the third in a series of articles highlighting lessons from China on the future of retail. The first article looks at how consumer behavior in China is evolving. The second article explores how the online consumer journey is changing. The fourth focuses on how retailers can How Companies in China Blend Digital and Physical Commerce.

When many Western consumer companies develop a new product, they set out on a long, slow process with an uncertain outcome. That’s because innovation typically starts internally, with ideas that flow from the business to the consumer (B2C). A full rollout could take several months, and during that period, executives are haunted by a single question: “I wonder if this thing will sell?” All too often, it won’t, because by the time the product is finally available, the market has already moved on.

In the current business environment, this model for innovation no longer works, and China is at the forefront with a new approach: using customer insights, largely generated through digital interactions, to inform product development. We call it customer-to-business (C2B) innovation.

C2B innovation is becoming the norm in China. By closely following customer trends via e-commerce platforms, social media, and current events, Chinese companies can design new products that better reflect customers’ needs. These products are then quickly produced and distributed through a few select channels. Winning products are rapidly scaled up, those that do not catch on are quickly withdrawn, and the company regroups to focus on a new opportunity. The entire process, from idea to launch, takes weeks rather than months.

The best companies in the West are beginning to apply this approach, but many more have a long way to go. This article—the third in a series about how Western companies can learn from China—discusses how companies in China have been able to refine the approach and how Western companies can create the conditions needed for demand-driven innovation.

Why China Leads in C2B Innovation

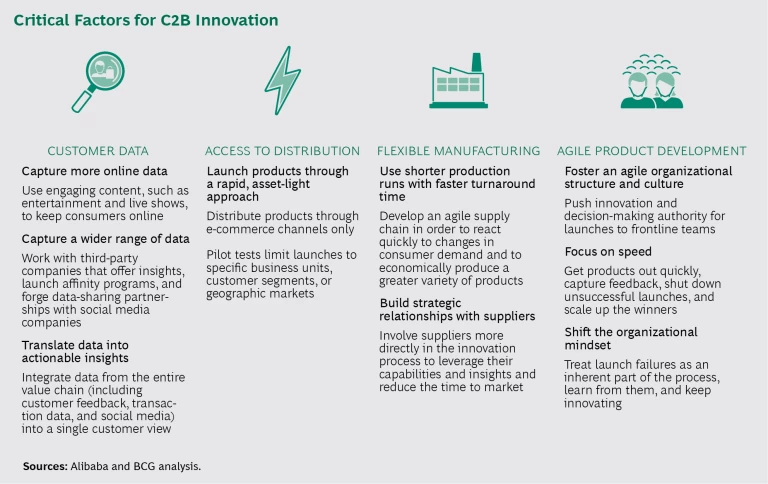

China’s e-commerce market, which leads the world in terms of total volume and penetration, can best be described as energetic chaos. In 2016, a greater volume of goods was sold online in China than in the US and the UK combined. (See “What China Reveals About the Future of Shopping,” BCG article, May 2017.) Four aspects of the market lead to C2B innovation. (See the exhibit.)

Customer Data. Chinese consumers typically spend more time online than people in most other markets, and they spend that time on a concentrated set of e-commerce sites, such as Alibaba’s marketplaces, Taobao and Tmall. Brands choose to set up and promote a storefront on Tmall rather than create a standalone site, and the overall experience is more engaging than Western e-commerce sites, which focus more on efficiency (Amazon’s one-click model, for example). Rather than merely listing product features and ratings, e-commerce sites in China include entertainment, social sharing, and community options, along with accurate recommendations based on a customer’s profile. Each experience, therefore, is personalized and allows the customer to offer feedback. E-commerce is also embedded into social media and content distribution sites. (See “The Chinese Consumer’s Online Journey from Discovery to Purchase,” BCG article, June 2017.)

The bottom line: companies operating in China have access to far more data, from a wide range of sources, along the entire path to purchase, and they are able to integrate it all into a single, coherent view of individual consumers. Every day in 2016, for example, users on Taobao and Tmall shared 20 million product reviews and posted 2 million questions about products to Q&A forums. Leading companies are effectively using bots and machine learning to track and process large volumes of real-time customer input from social media, transaction data, and customer feedback. This efficiently turns rich data into insights about consumers’ preferences and unmet needs.

Increasingly, this data is being used to shape new product launches. For example, Midea Group, a durable-goods manufacturer, designed a new dishwasher on the basis of consumer insights that Tmall had captured from consumer data. Online product reviews showed that consumers were looking for such features as easy cleaning of Chinese utensils, storage space, high-temperature drying, and control of the appliance through smart phones. The dishwasher, which launched on Alibaba in 2015, sold 38,000 units on Tmall in 2016.

Similarly, L’Oréal’s SkinCeuticals brand used data to reformulate and reposition its products to appeal to younger customers, with smaller package sizes and a focus on acne treatment rather than moisturization. The shift resulted in a 71% increase in ROI.

Access to Distribution. According to Alex Rampell, a general partner in the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, “The battle between every startup and incumbent comes down to whether the startup gets distribution before the incumbent gets innovation.” E-commerce, however, largely solves the distribution challenge for companies. With penetration rates that are higher than anywhere else in the world, and less retail infrastructure to manage, companies in China don’t have to spend much time thinking about distribution. Most online purchases go through one of a small number of very dominant online platforms, giving large and small brands an easy and economical means of getting new products in front of consumers nationwide.

In China, this has meant the emergence of thousands of internet-only companies, which grow revenues with a very limited outlay of capital. But the benefits are not limited to traditional categories, such as fashion and consumer goods. For example, Yili Group, a privately owned dairy company in China, has been using data from marketplace forums to better understand customer demands and inform all stages of the innovation cycle, from research to manufacturing to distribution. Data insights help Yili to identify unmet needs, test formulations and packaging, and more precisely target customers. As a result, the company has reduced the time required for development of the initial concept to full launch from a year and a half to just three months. Furthermore, Yili is on track to launch three times as many products in 2017 as it did in 2016, many of which are distributed only online, allowing the company to keep pace with the changing preferences of consumers.

Flexible Manufacturing. Companies operating in China can readily tap into the country’s strong manufacturing base and take advantage of flexible approaches, such as small-volume runs and frequent changes to production lines. Geographic proximity helps as well: companies are simply closer to their production facilities, reducing transit time and logistics. By contrast, Western supply chains typically establish the specifications and volume of a factory run far in advance and then ship finished goods back to complex distribution networks abroad.

The fashion industry is at the forefront of this shift to faster distribution. In China, “fast-react” suppliers enable fashion companies to sell products before they are even manufactured. Sale to delivery takes place within three days.

Agile Product Development. When e-commerce emerged, China’s consumer companies were less mature than their competitors in the West. That immaturity, which initially seemed like a hindrance, has quickly become an advantage: these companies do not have a decades-long legacy of physical retail operations and habits to unravel. Instead, a flood of newer brands and more entrepreneurial companies have emerged, with faster decision making, diminished bureaucracy, and less institutional inertia—leading to a far more vibrant market in which speed is a key differentiator.

For example, Three Squirrels, which sells packaged nuts, is China’s first—and currently largest—online-only snack foods company. In 2015, just three years after launch, Three Squirrels’ revenue reached $319 million. This was mostly due to smaller, agile teams that closely follow market developments and quickly adjust the product attributes in response, without having to unwind entrenched legacy processes.

How to Recreate C2B Innovation in the West

This approach to innovation—faster product launches fueled by consumer insights and agile processes—will soon become the norm worldwide. The following are some of the ways that Western companies can adapt what is happening to China in their home markets.

Access consumer data from a wider range of sources. Companies in the West don’t have the advantage of centralized e-commerce sites where consumers spend most of their online shopping time. Nevertheless, they can take strategic steps to gather the maximum possible data on their consumer base. For example, retailers in the US and Europe have access to Dunnhumby, a data insights company owned by Tesco, which aggregates and analyzes customer data from more than 1 billion customers worldwide. Dunnhumby supplements largely offline data with online data through its recent acquisitions, BzzAgent and Sociomantic. The company sells the data back to suppliers and other retailers and is starting to offer richer analytic services. Another approach is to develop a network affinity program, which can dramatically increase the amount of data a company can access. Increasingly, these partnerships include social media companies, such as Facebook.

Moreover, companies can rethink how they interact with customers online. For example, many Western companies simply focus on feedback in the form of ratings—aspiring, for example, to a five-star rating on Amazon. Chinese companies however, try to foster productive dialogues with customers so that shoppers can provide rich, detailed feedback in near real time.

After collecting data, companies in the West need to translate it into the basis for actionable insights and specific changes to product designs. Capturing data from a wide range of sources complicates this challenge, but new tools are emerging to help companies separate the signal from the noise.

Get products to market faster. Rather than follow the traditional product development approach of lengthy pilots and carefully planned national rollouts, companies in the West need to find opportunities for rapid, asset-light launches. For example, launching a product through e-commerce channels alone can dramatically simplify distribution. Dedicated complex supply chains supporting a network of far-flung physical stores are not an advantage when the objective is speed.

This approach requires a shift in mindset because some launches will inevitably fail. Leadership teams should treat such failures as an expected part of the process. The goal should be speed: getting products out as quickly as possible, capturing feedback, shutting down launches that don’t catch on (without stigmatizing the team that worked on them), and scaling up winners. Similarly, pilot tests can limit a launch to a specific business unit, customer segment, or geographic market.

Take advantage of flexible manufacturing. C2B innovation requires a supply chain that is designed for the agile manufacturing of new products, often in smaller batches, quickly, and at low cost. This is a significant departure for many companies. Traditionally, companies in the West have built a competitive advantage by going abroad for sourcing, by committing to longer runs and lead times, or by bringing all manufacturing in-house through vertical integration.

Today, some Western companies are bringing manufacturing back, closer to home. AllSaints, a British design-led fashion and accessories brand, is attempting to create a third way. It is developing a model that uses Google’s cloud-based communications platform to link London-based designers, global product merchants, and technicians to their sourcing operations and vendor partners in Portugal, Turkey, India, and various countries in Asia. Moreover, AllSaints aims to convert all analog production processes to digital. The company shares digital tools with its key global vendors and partners, so that all entities can react to global market dynamics and fashion trends. This has dramatically improved the company’s time to market without sacrificing design or quality standards.

Apply agile principles and push decision-making authority to the teams that are closest to the customer. Many multinational companies struggle in fast-moving markets, such as China, because they try to apply top-down, centralized decision-making processes. They rely on headquarters to make decisions, rather than adapting them to the demands of the local market. Successful companies are not only moving decision making closer to the local market but also using agile, cross-functional teams that react faster and with a more holistic view of any given opportunity. The concept of agile product development, which shifts from the classic waterfall approach to a more consumer-driven, iterative approach, significantly reduces the time to market. Companies across industries are beginning to apply this approach, and as they do, they find that they also need to alter their organizational structure and culture to support the change. This is a new way of working—indeed, it is also a new way of thinking about how the company creates value. Adopting this approach will require multinationals to rethink many aspects of how they operate.

China’s C2B approach to innovation requires companies to capture customer insights from online and offline sources and to deliver a superlative, seamless experience to customers in both channels. The next article in this series will explore the topic of omnichannel optimization in detail.