Even before the coronavirus pandemic erupted around the globe, the easy period of economic expansion in the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region was coming to an end. The US-China trade war and broader economic uncertainty had already slowed organic growth—and M&A deal activities began to pick up speed in the region as companies sought growth through inorganic means.

Recently those deals, too, have slowed down. But even as equity and deal markets undergo a correction in the first half of 2020, we believe that M&A deal volume in the region will stabilize—and that investment activities will resume—once the disruption of COVID-19 fades. (See “COVID-19 Doesn’t Change the Long-Term Perspective for M&A.”) That will be particularly true if a prolonged correction in equity markets further reduces asset prices from their recent highs.

COVID-19 Doesn’t Change the Long-Term Perspective for M&A

COVID-19 Doesn’t Change the Long-Term Perspective for M&A

The COVID-19 outbreak has upended economies around the world, and dealmakers in APAC are concerned about the impact of the pandemic on M&A activity. We understand that concern and acknowledge that uncertain cash flow projections has severely reduced activity in global M&A and related credit markets in the past months. We also believe that investment opportunities still abound, for several reasons.

Companies in APAC and global institutional investors such as private equity firms held approximately $350 billion in “dry powder” (or uninvested capital)—a historically high level—as of late 2019, according to data from Preqin. Those organizations will increasingly look to put that capital to work. We also see reduced valuation levels as a key catalyst to future deals, and we believe that structural changes and a “new normal” in certain industries—such as aviation, online shopping, remote collaboration—will lead to new business models and emerging transaction themes.

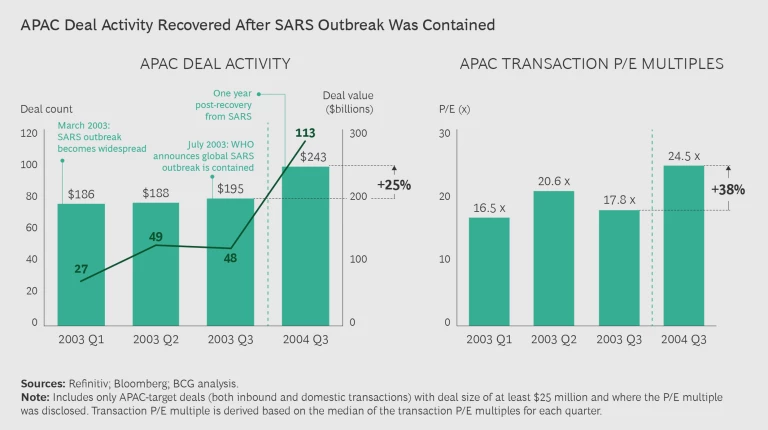

Moreover, looking at previous crises shows that deal activity returned to healthy levels. For example, following the SARS outbreak, the M&A market recovered within six months of the crisis ending. Deal volume increased by 25% after the World Health Organization announced that the outbreak had been contained, from the third quarter of 2003 to the third quarter of 2004. Valuation multiples rose by 38% over the same period, indicating fierce deal competition during the recovery. (See the exhibit.) SARS is also widely credited with accelerating the adoption of online shopping in China, and specifically with internet giant Alibaba’s dramatic growth since then.

To be clear, COVID-19 will likely have a bigger and longer-lasting impact on the global economy. But the key factors for successful M&A remain the same: an investment thesis of mid- to long-term growth, thorough due diligence, and strong post-merger integration. That has been the winning formula for M&A deals conducted during turbulent periods in the past, and it holds true today as well.

In today’s environment, companies that want to continue growing will need to do so through inorganic measures, including M&A, joint ventures, and minority investments. Many companies in the region, however, are not experienced in the inorganic growth model—including how to identify targets, close deals, and integrate new assets—for a good reason: they simply didn’t have to do it in the past.

We recently analyzed the landscape of transactions in APAC, including both minority-stake deals (which tend to be more common in the region) and full M&A buyouts.

The good news is that the transaction market in APAC still offers significant opportunities for those willing to build the right foundation.

Here we discuss the attributes that make deals in the APAC region more complex, both for local buyers and sellers and those outside the region. It also discusses the recent slowdown in transaction value, and the challenges among APAC buyers that limit their ability to grow through deals. Last, we offer a set of recommended capabilities that are essential for any investors looking to execute transactions in the region, particularly in weak economic times.

Recent Developments in the APAC Transaction Market

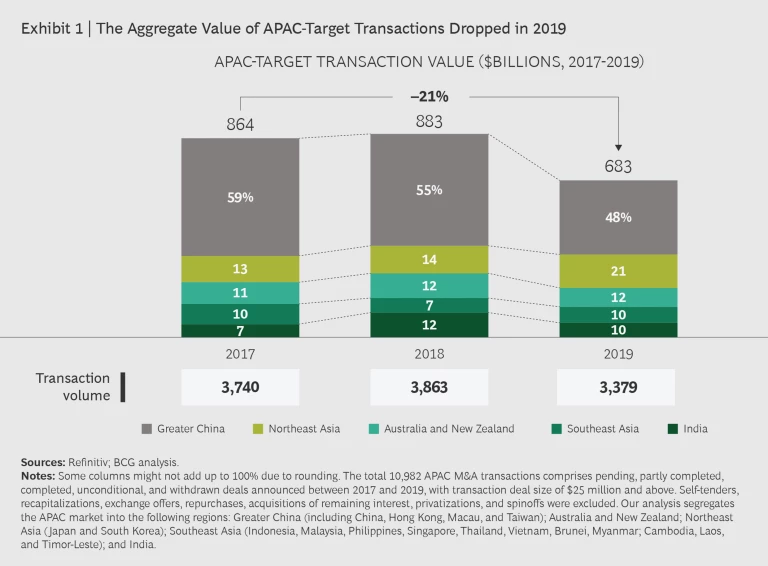

Across APAC, the overall pace of transactions is slowing in terms of both deal values and volume. Regarding values, the region’s uncertain economic prospects are causing some investors—particularly company acquirers—to remain on the sidelines, reducing the bidding for attractive targets. As a result, the aggregate value of APAC-target transactions declined in the region in by 21% between 2017 and 2019. (See Exhibit 1.)

Transaction activity varies by region. Overall transaction values for Greater China declined in 2019 (a 33% contraction compared with 2018), as dealmakers remained hesitant amid ongoing trade war uncertainty. India declined by 39% as investors shied away from very high valuations. The combined Australia and New Zealand market similarly declined by 20%, because of high valuation levels and a slowdown in domestic energy and mining. Inbound M&A—particularly from China—reflected the impact of political tensions.

Northeast Asia (which we define as Japan and South Korea) registered the highest increase in deal value (16%), fueled by M&As between companies in those two countries. Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Brunei, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Timor-Leste) showed a slight increase in transaction value growth (2%) as the region continues to present fundamental opportunities in digital economy and infrastructure, spurred by the rise of global manufacturing sites being established locally.

Some sectors are more active than others. These are: industrials and materials (34% of 2019 deal value in the region); technology, media, and telecom (28%); and consumer (19%). Notably, the share of total deal value from TMT has decreased from 36% in 2017 to 28% in 2019, in line with overall lower valuations in the sector worldwide.

Cross-border outbound transactions continue to drop in volume. Overall, the pace of cross-border outbound transactions in which an APAC buyer acquires a target in another market continued to slow. More specifically, deals in which APAC companies buy North American companies—particularly Greater China buyers acquiring those in the US—declined, primarily because of the protectionist stance of governments globally and the uncertainty of US-China relations, including the ongoing negotiations over tariffs and trade. As long as that uncertainty remains, it is difficult to imagine deal flow resuming between the US and China in the near future.

The pace of cross-border outbound transactions in which an APAC buyer acquires a target in another market continued to slow.

For the entire APAC region, inbound transactions volume fell as well, primarily because of concern about the fundamentals of the export-oriented economies. India was the only market that showed an increase in inbound transaction volume, because of a country-specific change: the 2016 implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, which led to a surge of distressed asset sales in India. (Foreign companies continuing to seek growth in the region were a contributing, though smaller, factor in India as well.)

How APAC Transactions Differ

APAC’s position in the global transaction market has grown significantly over the last five years, reaching $0.91 trillion in 2019. That is smaller than North America’s $1.8 trillion in transactions in 2019, but bigger than Europe ($0.85 trillion). However, all regions have unique characteristics, and transactions in APAC have several attributes that company investors and institutional investors need to understand.

Small and medium-size transactions are most popular

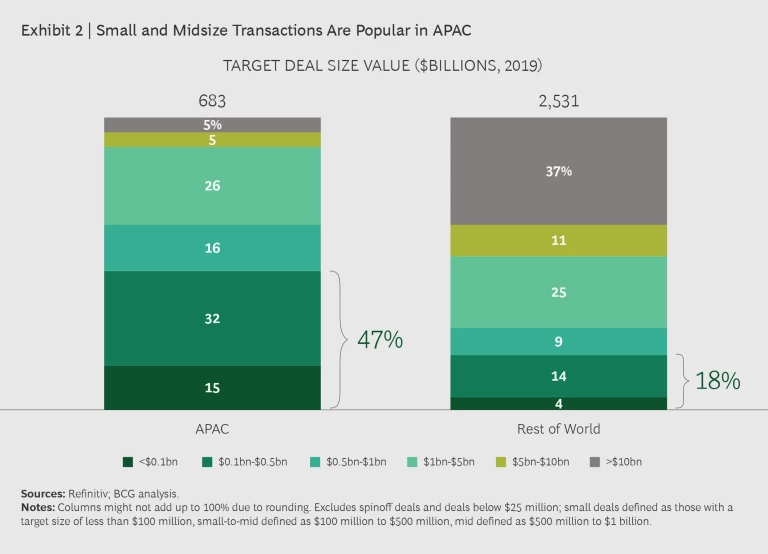

Compared with other markets, small and midsize deals (those with deal value of less than $500 million) are far more common in APAC, in terms of both deal volume and value. (See Exhibit 2.) For 2019, transactions of less than $500 million comprised 47% by value in the region, compared with 18% by value for the rest of the world.

These findings make intuitive sense in a developing market like APAC, where there are fewer large and established companies, and a highly vibrant, dynamic economy of small, fast-growing businesses. Mega-deals of more than $10 billion are exceedingly rare in the region.

Minority deals represent almost half of all deal value

Transactions for APAC-based targets are far more likely to involve minority stakes, rather than controlling stakes of more than 50% or full buyouts. Some 42% of aggregate APAC-target transactions for the three years from 2017 through 2019 were minority deals. Why? Investors understand that APAC and each market within it is unique, and learning from local partners is more efficient than trying to impose home-market strategies. India has the highest share of minority deals (57% of the aggregate India-target transactions from 2017 to 2019), while Australia and New Zealand have the lowest (14%).

For the rest of the world, by contrast, minority-stake deals made up only 10% of all transactions (by volume) from 2017 to 2019.

As with smaller deal sizes in the region, the prevalence of minority-stakes deals reflects the dynamic market in the region. Both corporate and institutional investors understand that APAC markets are unique—consisting of younger companies that may not have established processes and ways of working. Buyers rightly see that they may not be able to take over an acquired asset in APAC and implement strategies from their headquarters in the home market. Instead, they treat acquired assets as partners and learn from them about their ways of working.

Buyers rightly see that they may not be able to take over an acquired asset in APAC and implement strategies from their headquarters in the home market. Instead, they treat acquired assets as partners and learn from them about their ways of working.

A related factor is that full acquisitions are considered risky by some buyers in the region. They are more comfortable taking a smaller stake first that gives them exposure to a fast-growing asset but doesn’t require that they take on the responsibility for running it.

Finally, traditional private equity (PE) buyers are expanding to earlier rounds of minority investment to ensure that they have access for potential full acquisitions later on, especially regarding rapidly developing digital-economy-driven targets.

Investors are expanding into new industries instead of consolidating

A common deal strategy in any market is to buy multiple assets in the same industry and consolidate them, to expand their footprint, capture synergies, and generate scale efficiencies. That strategy applies in APAC, but a relatively higher share of buyers in the region is looking to explore new industries, compared with those in the rest of the world. For the period 2017-2019, nearly two-thirds of transactions involving an APAC buyer are in different industries, compared with 57% for those in other geographic markets.

And this diversification strategy also posted a better one-year relative total shareholder return (RTSR) of 22%, compared with acquiring solely within one’s core segment (13%). One explanation is that even though economic growth in APAC is slowing, it remains higher than in other markets. As a result, buyers can look beyond the traditional consolidation strategy and find growth in adjacent and differentiated industries, yet still create sustainable value.

BCG’s 2019 global M&A report reached a similar conclusion, finding that in a weak economy, acquisitions of business outside the buyer’s industry tend to create more value than traditional consolidation deals in the same industry.

Value-Creating Deals in Weak Economic Times

As the APAC region and the world are staring at the prospect of prolonged weak economic growth from the crippling effects of COVID-19 on businesses, dealmakers need to be aware that, historically, times of economic challenges in APAC have represented opportunities for value-creating M&A activity.

Historically, times of economic challenges in APAC have represented opportunities for value-creating M&A activity.

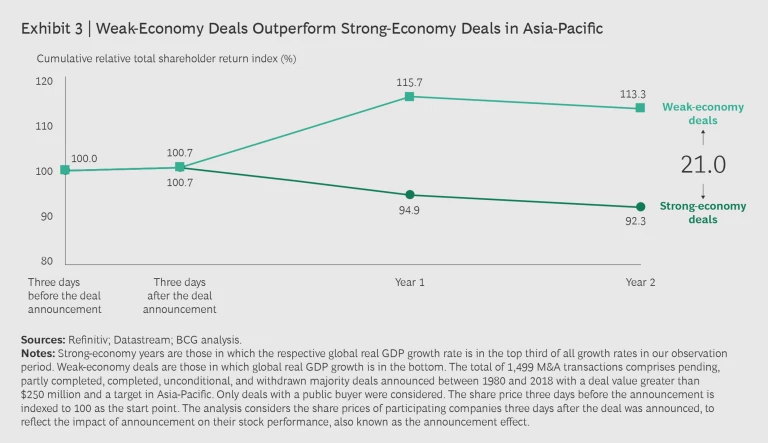

To reach that conclusion, we looked at approximately 1,500 transactions stretching back roughly four decades, and how value-creation was affected by the overall economy when the deal was struck. (Specifically, we looked at global GDP growth, and segmented years into thirds: the top third were years with the strongest economic growth, the bottom third were those with the weakest growth, and we excluded years that fell into the middle third.) That led to several key findings:

- A slow economy can lead to higher value-creation. Slow economies tend to make buyers nervous, but our research suggests that might actually be a good time to buy. For the deals we analyzed, those announced during weak economies generated better value—a difference in the overall relative total shareholder return (RTSR) index of 21 percentage points both one and two years after the deal. (See Exhibit 3.) The global analysis reached a similar conclusion, though the relative advantage was smaller than in APAC: roughly 7 percentage points one year after the deal, and almost 10 percentage points two years after. The key takeaway: Dealmakers achieved higher returns from investments made when the economy was weak. We believe there are a number of reasons why. First, valuations are lower, as economic uncertainty gets priced into assets, creating a larger margin of error. In addition, there is less competition for assets, as companies that may buy when times are flush become more conservative. Perhaps most important, buyers that are active in down economies tend to be highly professional and experienced, and they run M&A as an always-on function.

- In weak economic times, diversification pays. Our research shows that diversification deals outperform those in a single industry in APAC when economic growth is slow. The one-year RTSR for buyers diversifying their assets in weak economies is 16.5 percentage points higher than for acquirers piling up assets in the same industry. The market is clearly rewarding buyers willing branch out into adjacent sectors and thus diversifying their revenue and earnings streams.

- Serial dealmakers outperform in weak economies. Our research shows that two years after a weak economy deal, experienced buyers (those completing four or more transactions between 1980 and 2018) are 2.6 percentage points better off in terms of shareholder value compared with occasional buyers. This is hardly surprising, given that experienced buyers have the necessary tools and experience to execute deals amid heightened uncertainty. It’s worth noting though that even for occasional dealmakers in APAC, uncertain economic times may represent an opportunity. Normally these type of buyers experience a negative 9% RTSR after two years across our sample. However those brave enough to do deals in weak economic times are actually rewarded with a positive 8.2% outperformance.

Four Elements for Success

In the current market, we believe that four elements are critical for success in APAC transactions. (See Exhibit 4.)

1. Define a clear investment strategy.

A key challenge among many APAC buyers is that they might not have a solid, well-defined investment strategy, or a clear link between that and their overall corporate strategy. Instead, deals are more often brought to them by financial brokers or advisors, which leadership teams then assess on a deal-by-deal basis. As a result, APAC corporate buyers often take longer to analyze a potential deal and decide whether to pursue it.

To capture the M&A opportunity, APAC management teams need to think of transactions not as occasional events but as a continuous growth driver. They should take the time to define a clear, overarching strategy for inorganic growth, and set clear goals that are aligned with the overall corporate strategy.

To capture the M&A opportunity, APAC management teams need to think of transactions not as occasional events but as a continuous growth driver.

In addition, they should develop a portfolio and transaction strategy that supports inorganic growth, for both buying and selling assets. To support future transactions, management teams need to think through the financial aspect—whether it will create value by boosting revenue growth, increase margins, or improve cash generation—and not when a deal presents itself but in advance of that point. A comprehensive approach requires considering cash flow management, leverage ratios, and debt structures, along with determining a health leverage ratio for future acquisitions that balances debt and equity financing.

2. Make M&A capabilities a source of competitive advantage.

Given the historically low number of deals that APAC companies have likely completed, the second major area for buyers in the region to address is finding ways to build up strong capabilities in sourcing and assessing transactions. This is especially important because corporate buyers are competing with private equity firms and other sophisticated buyers that are literally built to do deals and have world-class investment capabilities in-house. In a competitive transaction market, that difference puts APAC companies at a serious disadvantage.

For example, some APAC buyers struggle to generate market intelligence, which would allow them to identify specific target sectors or the right growth stage of target companies (such as start-ups, fast-growers, or distressed assets that need turnarounds). In addition, some buyers apply a do-it-yourself approach to transactions. They don’t take advantage of external advisors and experts, instead opting to handle all aspects internally, often relying on an executive such as a finance leader who is evaluating deals as a side responsibility. It’s understandable that leadership teams would trust internal people more than outside experts, but they should be realistic about the level of expertise they can get from an internal person who may lack deep expertise in sourcing and evaluating deals.

To overcome these challenges, companies need to create a platform of capabilities to actively identify promising sectors and targets. Critically, this starts at the top—senior executives need to devote time and resources to corporate M&A, by establishing an internal investment team with broad functional, finance, and industry expertise and the ability to execute cross-border deals.

Senior executives need to devote time and resources to corporate M&A, by establishing an internal investment team with broad functional, finance, and industry expertise and the ability to execute cross-border deals.

The internal team need not do everything by itself. Instead, it can fill in gaps in expertise—such as in knowledge of capital markets, valuation, or turnaround processes—by working with external advisors or partnering with PE investors. The team should be proactively seeking deals, rather than waiting for offers from financial advisors.

3. Focus on strategy during deal execution.

Thorough due diligence is a critical aspect of deal execution, but APAC buyers typically focus on high-level risks, ensuring that the acquired company doesn’t have any major red flags in its financials. That is critical, but buyers also need to analyze future growth plans, competitor dynamics, and industry fundamentals.

For example, rigorous due diligence with a strategic lens should enable an acquirer to forecast a target company’s market share five years into the future, assuming it were to continue operating independently—that is, its standalone growth potential. The strategic due diligence process should also be able to gauge the increase in market share that a buyer could generate by combining its assets with those of the target. This is exactly the kind of due diligence that PE buyers conduct, and it’s simply not possible to do by looking primarily at risk factors.

To execute deals more effectively, APAC companies need to think of the target’s perspective. What does it want from a buyer? What is its ideal outcome from a transaction? In other words, buyers should ask themselves, “Why would a company want us to invest in it?” and have a clear answer. That should form the basis of an investment thesis: how the buyer will create value from the new asset.

4. Think about integration—before the deal closes.

APAC buyers often don’t sufficiently plan for what they’re going to do on Day One after the deal closes. There is a strong tendency to take over immediately, focusing on integrating the new asset into the buyer’s organization. That may be the right approach in some situations, but all too often, buyers don’t have the hands-on knowledge required to actually run the target business, and that doesn’t become apparent until it’s too late.

Similarly, some buyers don’t collaborate with the target company during the evaluation and execution processes. Sophisticated buyers are willing to ask the management team of an acquired company for ideas and insights about how to run the organization, and how it might continue to grow. Collaborating with the target’s management team at all stages of the transaction can help buyers ensure business continuity. More broadly, a mindset of mutual value creation can ensure that the best ideas and practices flow in both directions, from buyer to target and vice versa.

Finally, buyers need to have the right monitoring and reporting mechanisms in place once a deal closes. As with the value-creation aspect just discussed, the lack of monitoring and reporting mechanisms often stems from a lack of collaboration with the target’s management team during the early stages. Before conducting a massive integration effort, buyers should focus on how best to gauge and report the performance of the acquired company. That will ensure clear visibility into the underlying performance of the acquired asset.

As economic expansion slows across APAC, companies need to turn to transactions to continue growing. This is true even with the recent market upheavals due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, our analysis shows that value-creation is even more likely for deals executed during challenging economic periods. Dealmakers will only succeed, however, if they understand the market, address their biggest internal challenges, and build key capabilities. As deal activity picks up, companies that understand the market will be positioned to capitalize on it. Conversely, those that try to cling to old ways will be overtaken.