A BCG Fellow since 2008, Martin’s research focuses on the future of strategy. He has particular interests in adaptive strategy, the sustainability of business strategies, collective learning and innovation, and trust.

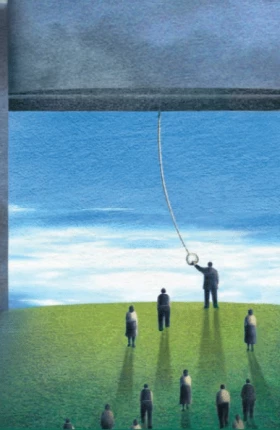

The world of business strategy has evolved since BCG’s founder, Bruce Henderson, defined the concept. Due to globalization, rapid technological change, and economic interconnectedness, today’s business environments are more diverse, faster changing, and more uncertain than ever.

Strategy, under relatively stable conditions, has historically relied on concepts of scale, efficiency, and first-order capabilities. But in a world of increased turbulence and unpredictability, leadership is less durable, industry boundaries are blurring, and forecasting has become much harder. We must therefore supplement traditional bases of competitive advantage with dynamic, adaptive capabilities and strategies.

In a live chat on LinkedIn on June 3, 2015, Martin Reeves—a BCG senior partner, the director of the Bruce Henderson Institute (BHI), and coauthor of Your Strategy Needs a Strategy—discussed how to select the right approach to strategy and answered questions about the book, the past and future of strategy, and the BHI.

Five Approaches to Strategy

How has strategy changed since BCG’s early days, when Bruce Henderson was pushing the topic?

In a sense, not much. We are trying to be on the leading edge in helping companies figure out how to win. Of course, the details have evolved quite a bit. The emphasis has shifted from strategies of scale and position, through strategies of capability, to the collection of diverse approaches we discuss in the book. I believe that we continue to have more than our fair share of influential ideas which shape the art of strategy.

What prompted you to write Your Strategy Needs a Strategy, and how did the collaboration work with your coauthors?

The genesis of the book goes back to two things. One was that when I took on the leadership of the Strategy Institute, I interviewed CEOs around the world on questions like What’s new in strategy? and Is strategy still useful? and What does your strategy department do? The answers were so interesting I decided to dig deeper. The seond was the constant demand from consultants on cases for an update to BCG’s strategy toolkit.

These two triggers led to many avenues of research over several years. Once we had our basic thesis, my coauthors, Knut Haanæs and Janmejaya Sinha, and I tested the ideas in CEO interviews around the world, so that we could have a genuinely global product. The actual writing of the book was very fast, at around six weeks, thanks to the incredible support I had from Kaelin Goulet and Thijs Venema, two ambassadors of the Strategy Institute—as well as many other contributors.

How does a company know which strategic approach is the right one?

Choosing the right approach is one of the central ideas of the book. We define five environments, which differ according to their predictability (Can I plan it?), their malleability (Can I shape it?) and their harshness (Can I survive it?). That’s the basis for choosing one of five approaches to strategy and execution. Those approaches are classical (planning), adaptive (experimenting), visionary (creating), shaping (co-creating), and renewal (surviving).

What insights did the gaming app, which accompanied the book, reveal that you maybe hadn't expected?

Our research suggested that accurately perceiving one’s environment, selecting the right approach to strategy, and then actually implementing it were not well correlated. In particular, many companies seemed to have an excellent understanding of the strategy approach required by the environment but then proceeded to “plan,” almost independently of that understanding.

That was one motivation for producing the game. The experience with the game reinforces the gap between understanding and action. We also saw that it was hard for players to be good at all approaches to strategy—and indeed it’s hard for companies to be what we call “ambidextrous,” too.

On Leadership and the Application of Strategy

What might make someone particularly good in one environment but less in another? Would you say some people, leaders, or companies have a tendency to overapply a particular approach?

Our interviews with leaders suggest that it’s quite rare for managers to be equally facile at all the approaches in the strategy palette. And consequently, they need to work quite hard to deploy the right people in the right places, to develop people by exposing them to different types of strategic challenge and by working around the deficit of ambidextrous resources by various organizational means. In the case of Pepsi, for example, the CEO has “run the business” teams working alongside “reinvent the business” teams in each part of the business.

In terms of why people are good in one environment or another, I think some organizations and people are just more naturally exploratory than others. And there is a tendency for organizations to lock into and be unable to walk away from a historic success pattern—as Bruce Henderson pointed out many years ago.

How do you advise mid- or upper-level managers to best apply the ideas of the strategy palette when they don’t have total direction over the strategy (or strategy-setting approach) of the company?

Leaders need to create consistency between the different aspects of a company “system” so that the right approach(es) can be applied. This consistency does not only apply to the thinking part: the incentive system, culture, and technology all have to be aligned. For example, there will be no adaptive strategy if risk taking is effectively sanctioned.

In terms of middle managers, the strategy palette can be applied at many levels: to a company, to a business, to a function, to a country, or to a particular problem. So in that sense, it’s not just for CEOs and whole corporations, but for anyone who wants to solve a problem in the most effective fashion.

How do leaders need to think differently about their roles today?

There are some leadership implications arising from the diversity of business environments. We did not initially intend to have a chapter on leadership in the book, but the CEOs we interviewed all wanted to talk about this.

Essentially, what we heard about was a new set of leadership challenges arising from the diversity, the dynamism, the complexity, and the uncertainty of environments. Compared to the traditional leadership approach of cascading instructions down a hierarchical organization based on experience and analysis/planning in a stable environment, we heard about the need to create new approaches to leadership.

For example, we heard about the need to lead different and perhaps contradictory approaches to strategy in different parts of the organization. We heard about the need to lead with questions when there is great uncertainty involved. We heard about the need to develop leaders and leadership teams which were equally facile with multiple approaches to strategy. We heard about the need to constantly destabilize organizations, to prevent them from locking into one way of thinking and behaving in dynamic environments.

Many CEOs stressed to us that from a leadership perspective, the main change in recent years is the need to run and reinvent simultaneously. That’s borne out by our analysis of the acceleration of business life cycles in recent decades. Overall, businesses cycle through the portfolio matrix twice as fast as they did 30 years ago. But in some cases, it’s much faster than even that, hence the need to run and reinvent in parallel.

It’s very hard to be dealing with streamlining and efficiency questions at the same time as trying to drive growth and innovation. Thus, we included not only the chapter on leadership, but also on the techniques which permit companies to be ambidextrous—to be able to run different approaches to strategy and execution at the same time.

On the Bruce Henderson Institute

What is the goal of the Bruce Henderson Institute? How is it different from BCG’s core functions?

The goal of the BHI is to anticipate and shape how managers will be thinking five to ten years from now by coming up with the next big ideas in each part of our business. This is something that BCG has always done, and done successfully, I would argue. But as a much larger company, we need to do so somewhat more systematically.

More than ten years ago, we founded the Strategy Institute to do this in strategy. The BHI will try to fulfill the same role for all aspects of our business.

What can we expect from the Institute in the near future?

We have a BCG Fellows program spanning our practices and geographies, and those thought leaders will be delivering big ideas on topics such as the future of energy markets, the future of market research, how to be successful in commodity businesses, what it takes for family businesses to be successful, the intersection of data and privacy, what it takes to succeed in large-scale change, how to harness the power of smart simplicity, and other exciting topics.

We are also founding a new Center for Macroeconomics, which will try to link macroeconomic developments to consequences and implications for corporations. And from the Strategy Institute, which we are renaming the Strategy Lab, we have some exciting new topics like “the self-tuning enterprise,” which we just coauthored a piece on with Alibaba, in Harvard Business Review.

Within the BHI, what is the Innovation Sounding Board and what is its role?

The Innovation Sounding Board is a group of senior leaders—including our CEO and the heads of our practices—who oversee, support, and guide the BHI and upstream research at BCG in general. They “kick the tires” of new ideas, select new BCG Fellows, and help us navigate and collaborate with the wider BCG. One of our big aspirations for the BHI is that it is not too internally facing—we will be experimenting with more outward-looking collaboration platforms, so that we can tap into thought leadership in our domain, wherever it is happening.