A revolution in the field of philanthropy is brewing, driven by Silicon Valley’s young tech billionaires. The founders of eBay, Facebook, PayPal, Napster, and other transformative companies are applying their bold vision and brash, nothing-can-stop-me attitude to some of the world’s most pressing social problems. Their drive and entrepreneurial spirit make them less concerned with the status quo and completely open to disruptive innovation. The sheer scale of their wealth and their commitment to giving it away mean that these philanthropists could have a huge impact on the issues they prioritize. What’s more, their approach—with its emphasis on data, transparency, speed, and impact—could mark a new chapter in philanthropic giving.

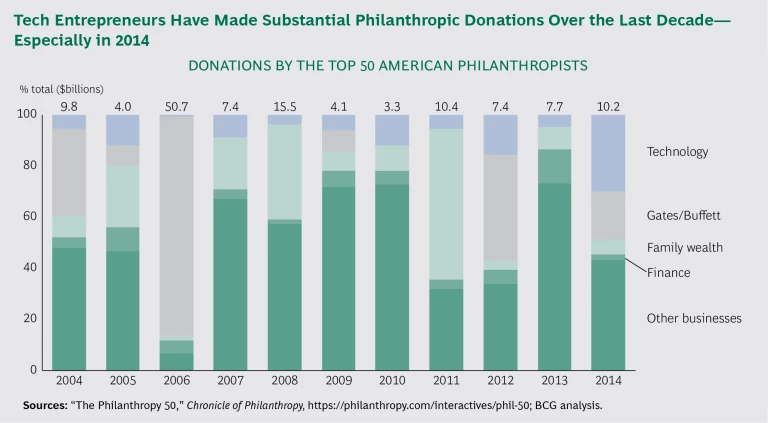

Once criticized for their relatively low levels of giving, today’s tech billionaires are quickly making up for lost time. Microsoft’s Bill Gates paved the way with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which since its founding in 2000 has dominated tech-funded philanthropy. Now a new wave of entrants—including Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Dustin Moskovitz; Skype founder, Nicklas Zennström, in Europe; PayPal cofounder and current head of Tesla Motors, Elon Musk; and Napster cofounder, Sean Parker—are investing their fortunes in hopes of making a dramatic difference. According to media reports, nearly 25% of the money given away in 2014 by the top 50 philanthropists in the US came from tech entrepreneurs age 50 or younger, compared with 19% in 2013 and 4% in 2012

These tech philanthropists are bringing fresh thinking and new approaches to the field of philanthropy.

Rethinking Philanthropy: Seven Principles

Traditional foundations—which award grants to applicants on the basis of need and worthiness—have made enormous contributions to society. But they follow a business model that relies on large endowments to support giving in perpetuity, which has given rise to a professional class of individuals who evaluate, select, and continuously review grantees.

Today’s tech philanthropists challenge that approach with an inherently proactive venture capital mind-set. Rather than wait for proposals to come to them, they actively seek places to put their money. They also prioritize speed and rapid impact. Determined to see results in their own lifetimes, they’re willing to make big, often risky bets. Some even treat their philanthropic investments like venture capital endeavors, applying creative equity models to ensure a return and demanding measurable results to justify further giving.

Although the results that these new philanthropists will ultimately deliver over the long term remain to be seen, they’re determined to disrupt the field—just as they did in their respective industries. Seven principles summarize their approach.

1. Seek breakthrough solutions. Many of today’s tech philanthropists are “swinging for the fences,” investing major sums in breakthrough, sometimes controversial, solutions to social problems and unafraid to take on high-risk projects. PayPal cofounder and venture capitalist Peter Thiel, Google cofounder Larry Page, and former Oracle CEO Larry Ellison have combined forces to defy death, with Ellison alone donating more than $430 million to anti-aging research. As Thiel puts it, “I believe that evolution is a true account of nature, but I think we should try to escape it or transcend it in our society.” Musk’s foundation donates millions in areas such as human space exploration. His cornerstone project, SpaceX, aims to create a space-faring civilization to help sustain Earth’s resources. Gates has brought the same approach to global health, challenging the scientific community to move past the traditional goal of controlling malaria and instead eradicate the disease completely.

2. Use business expertise to innovate. Many of today’s tech philanthropists use their technical expertise to tap into new or unconventional channels for social change, building social networks, creating new intellectual property models (to make products with a potential social impact accessible to those in need without forgoing commercial profit), and deploying new technologies. Thiel built on his experiences in the start-up and investing arenas to establish Breakout Labs, which uses philanthropy to support a growing portfolio of early-stage companies in areas ranging from food science and biomedicine to clean energy. The group provides “radical science companies” too risky for traditional venture capital with capital, network support, and access to partnerships in order to “change the world and take our civilization to the next level.”

3. Trust in the power of data. Big believers in the clarity that data can deliver, tech philanthropists monitor and measure outcomes and hold their investments to a high degree of accountability—not out of an aversion to risk but to ensure that they’re maximizing the impact of every dollar spent. Data and metrics are essential for gleaning the insights needed to evaluate the success of a chosen approach. Evidence-based approaches in philanthropy, also known as “effective altruism,” use data not only to evaluate ongoing results and outcomes but to identify areas in which to invest. For instance, Mike Krieger (cofounder of Instagram) and his wife, Kaitlyn Trigger, recently partnered with Moskovitz and his wife, Cari Tuna, to support the Open Philanthropy Project, believing that its values of “open-mindedness, rigorous analytical thinking, and transparency” are aligned with theirs. The Open Philanthropy Project identifies important but relatively unaddressed problems and funds feasible approaches to solving them, as determined by rigorous analysis, research, and ongoing data gathering.

4. Employ a rapid cycle of testing, failing, and learning. Another hallmark of tech philanthropists is a “prototyping” approach to solution building that involves rapid cycles of testing, failing, and learning—continually refining a path forward before moving to execution. This agile mind-set, which is standard in software development, accelerates outcomes through collaboration and a constant cycle of learning and improvement. Failing is acceptable as long as valuable lessons are learned along the way.

New solutions take time to develop and may go through many stages of trial and error before they’re ready for launch. Testing and rapidly fine-tuning new models before scaling them up can mean the difference between a breakthrough innovation and a wasted investment. Tech philanthropists are all too familiar with good ideas launched before they’re ready and bad ideas killed too late in the process. Either mistake is costly. What’s new about the prototyping approach for philanthropy is not the piloting of new ideas, which has gone on for decades, but the speed with which ideas are tested and the willingness to walk away if an idea fails—as long as there is a lesson learned. As Parker explains, “We must move fast, make concentrated bets based on our convictions, and have the courage to make mistakes and learn from them.” Similarly, in a letter announcing the gift of 99% of their Facebook shares to the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, wrote, “We must take risks today to learn lessons for tomorrow. We’re early in our learning and many things we try won’t work, but we’ll listen and learn and keep improving.”

5. Embrace an “open source” mind-set. Tech philanthropists prize transparency and sharing of data, ideas, insights, and solutions. Like open-source software development, this approach taps into the expertise of many and can accelerate progress. Openness also eliminates duplication of effort and increases the odds of maximum impact from the invested dollars. Last year, Parker announced the creation of the Parker Foundation to “aggressively pursue large-scale systemic change in three focus areas: Life Sciences, Global Public Health, and Civic Engagement.” The foundation’s planned structure will support an open-source approach within a network of partners, enabling leading scientists in each field to carry out collaborative research. Scientists receiving foundation funding are encouraged to share their findings early on with other scientists in the foundation’s network, regardless of institutional affiliation. Parker hopes that promoting the sharing of data and findings will lead to the next big breakthrough in the treatment of immune diseases.

The Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Research, initially funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, operates on a similar principle. It was founded in the belief that the successful development of an AIDS vaccine will require a collaborative approach emphasizing the sharing of scientific information and the standardization of techniques and analysis.

6. Recruit top talent and stay personally involved. Like many venture capitalists, tech entrepreneurs tend to play an active role in the organizations they fund in order to ensure that the large sums they donate achieve the desired results. For instance, Reid Hoffman, a founding board member and executive at PayPal and the founder and executive chairman of LinkedIn, stays involved in the grant-making process and often serves on the boards of recipient organizations.

At the same time, tech philanthropists know that putting the best and the brightest in the same room delivers creative solutions to problems—faster. So they take a people-first approach to identifying grantees, building teams, and recruiting board members. The talent pool that Parker, Musk, and former Google CEO Eric Schmidt can access with a single phone call is markedly different from what a lower-profile nonprofit can get from a job posting. With a reputation for innovation and an army of developers and resources at their disposal, they can secure some of the greatest minds for every endeavor, pulling in both leading industry experts and top talent from their own business endeavors to manage and advise on their philanthropic efforts. Thiel’s Breakout Labs employs PhDs from MIT and Berkeley, for example, while Jeff Skoll, the first employee and first president of eBay, counts former HP and Microsoft executives among the Skoll Foundation’s executive team.

Tech philanthropists also look to their tech peers for guidance in their philanthropic efforts. These billionaires often travel in the same circles, serve on one another’s company boards, and welcome targeted collaboration. Though they act indpendently in their philanthropic endeavors, they often cross paths, funding some of the same giving entities and exchanging advice.

7. Expect financial returns. Today’s tech philanthropists often have no qualms about reaping financial returns from their investments—a “venture philanthropy” approach that combines doing good with making money. For instance, Thiel’s Breakout Labs makes grants that convert to an equity stake when revenues exceed a certain threshold. Likewise, Kleiner Perkins’s John Doerr uses a venture capital-like model to distribute money to organizations such as the NewSchools Venture Fund. He expects investment returns in exchange for his financial contributions and strategic expertise.

This approach can open new avenues for reinvestment and free an effort from some of the restrictions of nonprofit status. When Zuckerberg and Chan pledged to dedicate 99% of their Facebook shares, they did so by incorporating as an LLC—a for-profit organization—to maintain a higher level of control and reserve the power to blur the lines between philanthropy, investment, and political advocacy. Others—including Pierre Omidyar and Steve Jobs’s widow, Laurene Powell Jobs—have taken a similar approach, with LLCs common across Silicon Valley’s philanthropic landscape.

Done right, these new ventures can generate enough money for continuous reinvestment, so that benefits and impact increase over time.

The Risk/Reward Trade-Off

Disrupting the field of philanthropy is not without risks. Technology entrepreneurs already hold enormous economic power in Silicon Valley and beyond. Their foray into philanthropy further extends the reach of a few luminaries and could discourage other players. For example, a massive infusion of philanthropic funds into a single school district or a narrow area of research could crowd out alternative approaches and other important players, such as government, private investment, or grassroots organizations. The resulting concentration of power could create policy conflicts or undermine those with deep experience in a particular area. It could also leave a void should the philanthropist decide to redirect funding toward a different cause.

What’s more, the venture orientation of some tech philanthropists could cause them to value only those philanthropic investments that generate a financial return. When scientists and thought leaders begin to worry more about making money than driving groundbreaking change, true progress can be a casualty. A competitive philanthropy model can hinder fundamental work in many areas. For instance, the demand for profit combined with a philanthropist’s star power could divert investment away from areas that need funding but are unlikely to generate a return—areas such as human rights and wilderness preservation.

Moreover, some of the features that make this approach so powerful can be risky if applied too freely. For instance, rapid cycles of testing, failing, and iterating work better for software development than for social welfare programs, on which livelihoods depend. When there is little margin for error, failure can be catastrophic.

By definition, disruptive philanthropy challenges the effectiveness of traditional ways of giving. And although philanthropy, like wealth, is not a zero sum game, competition among funding entities is not the goal. The call to action for tech philanthropists is to choose their giving strategies wisely and engage deeply with stakeholders in order to mitigate the risk of insularity among their own small community. A disruptive and innovative approach does not mean ignoring the lessons of the past, but rather learning from them and breaking out of the box that constrained conventional thinking.

Looking Forward

In the for-profit world, disruption is a proven force. It can deliver newer, faster, more effective—even transformative—products, services, and ways of working. Will applying a disruptive approach to philanthropy unlock new discoveries, cure social ills, and advance humanitarian goals on a grander scale and a faster timetable, as these billionaires hope?

The tech philanthropists’ expectations of breakthrough change and rapid outcomes may be the result of their enormous past successes—combined with the hubris of youth. Gates has said that he started his foundation with the same fervor that he brought to Microsoft, but he came to realize that many problems were more complex than he had assumed and were not easily solved, even with the benefit of many years’ efforts. As a result, he’s steadfastly retained the mind-set of an “impatient optimist,” while his foundation’s approach has evolved from finding technical solutions to more systemic problem solving. As younger entrepreneurs move along that same experience curve, we may see significant changes in their approaches as well.

Still, the commitment of the tech billionaires to new ways of working, unprecedented use of data, analytical rigor, information sharing, and unwavering focus on measurable outcomes may yield important insights about the best models for philanthropic success, a welcome possibility in this critical field.