Politicians are often disappointed with how long it takes to implement policies and how much the final outcome can differ from what they or their stakeholders expect. Meanwhile, citizens who want quality services are often let down by second-rate digital solutions and the complexity and impersonal nature of their dealings with government. Taxpayers are frustrated by stories of failed projects and the waste and inefficiency of a system that tends to value process over outcomes. And in a risk-averse environment of hierarchical and bureaucratic silos, talented, mission-driven public servants become disillusioned. With the gap widening between expectations and what’s being delivered, governments need to fundamentally transform the public-sector operating model. The key to doing so could be the practices collectively known as agile.

An approach to software engineering that emerged in the early 2000s, agile is quickly becoming a new organizational paradigm. Using agile methodologies, multidisciplinary teams work in fast, iterative sprints. Most governments are likely to have adopted some form of agile when implementing technology projects, and some public-sector organizations are using it in the delivery of digital services. What is new is the idea of applying agile ways of working at scale across an enterprise. Private-sector organizations such as ING Netherlands have done it and are reaping significant benefits. Increasingly, public-sector organizations, such as the World Bank, are likewise beginning to adopt agile at scale.

The potential benefits to all stakeholders are considerable, but implementing agile is not for the faint-hearted. Structures, processes, behaviors, and cultures that have evolved over decades are hard to shift. The public sector also faces unique challenges in the need to operate within legislative frameworks and the nature and timing of political decision making. It must work with less labor flexibility, including constraints on layoffs and rigid job descriptions, levels, and remunerations. Moreover, unlike other organizations, governments must constantly consider the voters.

But organizations that make the shift to agile can deliver higher-quality programs and services more efficiently and with less risk. And by giving employees greater autonomy—accompanied by clear guidance and leadership on purpose and strategy—they can unleash the huge productivity dividends currently lying dormant within today’s public-sector workforce.

The Benefits of Agile

Digital technology has had a transformative impact on the way people consume services. Apps, chatbots, and virtual assistants allow them to access services anywhere at any time. As these technologies drive new consumer behaviors across industries, citizens’ expectations of public services are also changing, and many governments are responding by investing in digital capabilities. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and predictive algorithms could enable dramatic improvements in policy analysis and service delivery. But while technology is a powerful tool, it can be hamstrung by legacy structures, cultures, and ways of working. In the public sector, agencies—and even internal functions—tend to be siloed, and leaders are incentivized to focus on their own vertically organized and sometimes competing domains.

When scaled up, agile breaks down functional silos, increases transparency and accountability, and empowers employees.

By contrast, agile helps teams organize to deliver high-quality outputs quickly. It involves a shift in mindset that prioritizes a clear, overarching vision over prescriptive detail. It facilitates flexible leadership and organizational structures, cross-functional teams, ecosystems of talent, and collaborative cultures and behaviors. When scaled up and applied across an enterprise, agile breaks down functional silos, increases transparency and accountability, and empowers employees.

Agile uses an iterative “minimum viable product” methodology, in which features of a product or service are developed sufficiently for first users to grasp the concept and provide feedback. That feedback informs the next iteration, which is shared with a larger number of users, and so on until the product or service is being used at scale.

This approach leads to faster, more effective product and program design than is possible using the traditional “waterfall” methodology. With waterfall, separate groups design and build a product or service in sequence. Each group must wait for the preceding team to complete its work before moving ahead. Besides being slower than agile, the waterfall method carries the risk of misunderstandings during handoffs, which can require work to be redone. In contrast, agile’s process of continual testing and iteration not only improves products and services but also reduces the risk of implementation failure. In fact, research by the Standish Group indicates that agile ways of working cut this risk almost in half.

Agile at Work

We have seen these powerful effects at work in the corporate sector. When ING Netherlands adopted agile methods, it increased both speed to market and customer centricity in the face of tremendous disruption in the financial services industry. ING was inspired to change its approach by the ways of working of digital natives such as Netflix and Spotify. In addition, the adoption by Zappos of “holacracy”—in which decision making is distributed across self-organizing teams rather than being assigned by a management hierarchy—inspired the transformation of ING’s call centers and operations. Numerous companies, including Renault−Nissan−Mitsubishi, have likewise implemented agile to transform their business operations.

Agile has applications in the design and continuous improvement of services that are more customer-centric and efficient.

Agile has been applied in the public sector, too. For example, after the World Bank rolled out agile ways of working across the organization, the impact of its global development programs increased and employee engagement improved. (See “Agile at the World Bank.”) The UK’s Government Digital Service, the US Digital Service, and 18F, a unit within the US General Services Administration, are examples of the same thinking and approaches at scale.

Agile at the World Bank

Agile at the World Bank

In 2014, the World Bank—which operates in 110 countries with a staff of 17,000—worked with BCG on a series of projects to help rebuild its operating model after instituting a major reform that transformed the organization from numerous regional silos into a global enterprise.

There were several challenges. It was taking the bank up to three years to approve loans because of multiple review cycles, long wait times, and a proliferation of checkers versus doers. Management had many layers, the ratio of direct reports to managers was too high, and meetings were inefficient—often with more than 20 participants, each of whom had a chance to speak in turn. As the former head of operations, Kyle Peters, put it at the time: “Our staff love what they do, but they hate how they do it.”

The bank needed to become more nimble. That meant reforming the organization and management of teams, clarifying which individuals were empowered to make decisions, reducing complexity, and eliminating redundancy from internal processes. An agile methodology provided a framework for a staff-led transformation, with no top-down mandates or targets and the opportunity to test changes in four-week sprints.

Meanwhile, new tools and practices were introduced to prioritize activities, track impact, run meetings, and allocate work, with feedback supporting continuous improvement and a collaborative culture. BCG coached ten “agile fellows” for 12 months, teaching them to be the change makers who would sustain the bank’s journey.

Agile proved successful. In year one, 90% of pilot participants said that the interventions they tested saved time and improved quality, the board approved two policy change proposals, and employee engagement scores improved.

In these and other organizations, the transformation has occurred not by changing individual projects or departments but by moving large parts of the organization, or even the whole enterprise, to a new way of working—one that provides an effective means of tackling a wide variety of entrenched problems. In policy settings, agile can help set the clear policy goals needed to prioritize and structure the work. It can be used to run test-and-learn experiments in order to determine the best way to achieve a desired outcome, often enabling more cross-departmental collaboration. And it has wide applications in the design and continuous improvement of services that are more customer-centric and efficient and more rapidly introduced.

Implementing Agile in Government

Agile is not a silver bullet. Nor is there a one-size-fits-all model that can be easily transferred from the private sector to government. No one should underestimate the challenges governments will face in adopting agile ways of working.

Government organizations have generally been designed to develop services and implement programs using the waterfall approach. But multiple targets and differing policy objectives in the public sector can create complexity and conflict, making it hard to set goals. Changing longstanding governance, budget, and funding models can be particularly difficult.

Agile demands other changes as well. Measurement and accountability frameworks need to be redesigned, internal and cross-agency silos broken down. Organizational culture, leadership styles, and professional mindsets need to be reoriented.

Agile is not a silver bullet. No one should underestimate the challenges government will face in adopting agile ways of working.

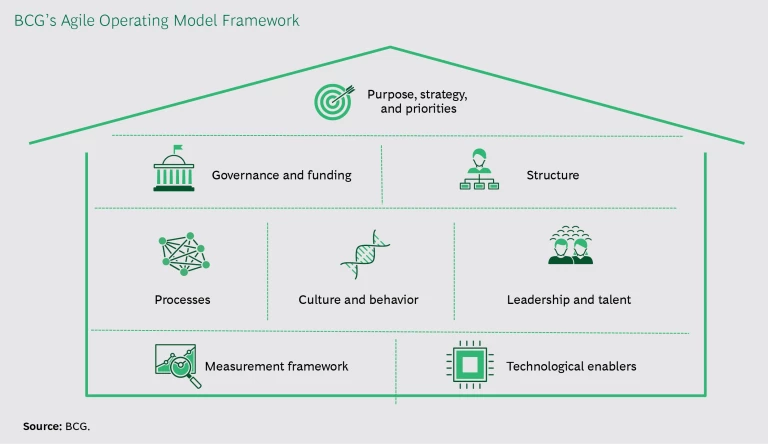

Despite the challenges, interest in agile in government is growing. While approaches will vary, a number of key areas must be addressed in any transformation. These make up the agile operating model framework illustrated in the exhibit.

They include:

- Purpose, Strategy, and Priorities. Agreement on these is essential before an organization can allocate resources appropriately and start to build the infrastructure that agile calls for. Ensuring that everyone is clear on purpose and strategy and understands why and how the organization must change is critical to enabling autonomy at all levels.

- Governance and Funding. Organizations should move to a more flexible, capacity-based funding approach, with regular reevaluation of initiatives to ensure that they are on track and merit continued funding.

- Structure. Flatter organizations with wider spans of control and clearer accountability and ownership of programs empower the workforce to take responsibility for decision making and problem solving. Line managers then become coaches and facilitators rather than bosses.

- Processes. Cross-agency coordination, cross-functional teams, and close cooperation with citizens are essential to flexible, multidisciplinary ways of working.

- Culture and Behavior. At the heart of an agile transformation is a change in culture and behavior. Agile prioritizes autonomy at all levels and empowers teams to experiment with alternative solutions to problems. But autonomy can descend into chaos unless teams at all levels are clear on purpose and strategy. That depends on strong leadership and clear and frequent internal and external communications.

- Leadership and Talent. Besides hiring and promoting top talent, organizations must base rewards on outcomes and peer feedback, with a focus on developing expertise and new career paths—practices that have yet to be widely adopted in the public sector. Leaders need a comprehensive understanding of the mission, purpose, and underlying principles of the transformation in order to ensure that teams at all levels are clear on the “why”—the organization’s strategy and purpose. Then they need to let go, abandoning traditional command-and-control models and allowing teams to figure out the “how.”

- Measurement Framework. To assess progress toward goals, data analytics should be more widely deployed across the organization. Transparency in measurement frameworks is essential and can be achieved by using digital tools and analytics to empirically assess and track improvement. Critically, data must be widely available throughout the organization.

- Technological Enablers. Agile requires a transition from heavy mainframe to more modular systems that give teams greater ownership of their end-to-end processes. Essential elements include the use of APIs (application programming interfaces); shared tools to manage the flow of work from idea through development and into customers’ hands; continuous delivery, automated testing, and DevOps (which unifies software development and operation); and a defined technology architecture that identifies the data important to the organization and the systems that create and manage it.

Of course, as with any large-scale change effort, resistance is likely to emerge along the way. The transition to agile can, for example, create uncertainty among many in the workforce. It’s therefore essential for leaders to be clear on what everyone’s role will be in the new organizational structure. Agile is a highly transparent way of working and some may find that uncomfortable. And since it brings about a fundamental shift in the way citizens are served, effective change management is critical.

Starting with pilots in one or two areas can build trust, allowing others to see the benefits and paving the way for adoption and rollout throughout the organization. Conversations about the deployment model and how to make the pilots successful are also essential. But while a variety of tools, processes, and methodologies can be used to support agile—from collaboration software to daily stand-up and retrospective meetings—these must be complemented by a corresponding change in mindset.

Changing institutions characterized by highly centralized, top-down decision-making processes and risk-averse cultures will be tough. But governments have little choice. Citizens expect to get what they need from the public sector easily and quickly, to provide feedback on the services that they receive, and to add their voices to decision making—at any time and from anywhere. Governments that make these things possible will find that they can unlock the latent potential currently trapped inside the public-sector workforce, while reaping the benefits of greater operational efficiencies and a new, more effective relationship with their citizens.

A forthcoming article will focus on the unique challenges of implementing agile in the public sector.