This article—the third in a series exploring the practicalities of going public—looks at what’s necessary for a successful IPO in today’s market, particularly when seeking new capital. The first publication, “Anatomy of an Ideal IPO Candidate,” examines how companies can overcome the barriers to going public and survive the scrutiny of the capital markets. The second, “What Really Matters for a Premium IPO Valuation?” analyzes some of the tools that companies can use in the effort to yield a higher IPO listing price.

The global IPO window is still open after the launch of several long-awaited mega IPOs this year. Prominent examples of the latter range from ride-hailing services Uber and Lyft to more traditional businesses such as Volkswagen’s truck unit Traton and Swedish private equity firm EQT.

Yet some of these IPOs have been far more successful than others. Our recent study reveals that companies that are using their IPOs only to sell existing shares have had more positive outcomes than those that went public at least in part to raise fresh capital. (See the sidebar, “Study Methodology.”) And this finding holds true beyond recent IPOs: we see similar results going back as far as 1990.

Study Methodology

Study Methodology

BCG’s study initially sampled approximately 43,000 IPOs from January 1990 through September 2019. The data set was assembled using several state-of-the-art financial databases such as Refinitiv (formerly Thomson Reuters Financial & Risk) and S&P Capital IQ.

To arrive at the data set we used for the analyses in this article, we performed several data-cleansing steps, such as removing duplicate entries for simultaneous listings on multiple exchanges or excluding trusts and financial holding companies. We did not consider any secondary issuances—that is, capital increases after an IPO. The proceeds include capital raised on all markets, including any overallotments.

To investigate IPOs’ postlisting performance, we calculated the total shareholder return (TSR) for each newly listed company in the six-month, one-year, and two-year period from its listing date. The TSR is a commonly applied performance figure and captures capital accretion (share price changes) as well as dividend payments.

To analyze the effect of a capital raise at IPO, we looked at listings with new shares only (in other words, those where only newly issued shares from a capital increase were offered to the public), IPOs with existing shares only (where shares were exclusively offered by existing shareholders and no capital increase took place), and mixed IPOs.

When a company issues new shares through an IPO, investors seem to need a more compelling equity story than they do when the listing involves no new capital raise. And we find that four factors exacerbate the performance disparity: historical growth momentum, deal size, free-float percentage, and industry sector.

The IPO Market Remains Buoyant

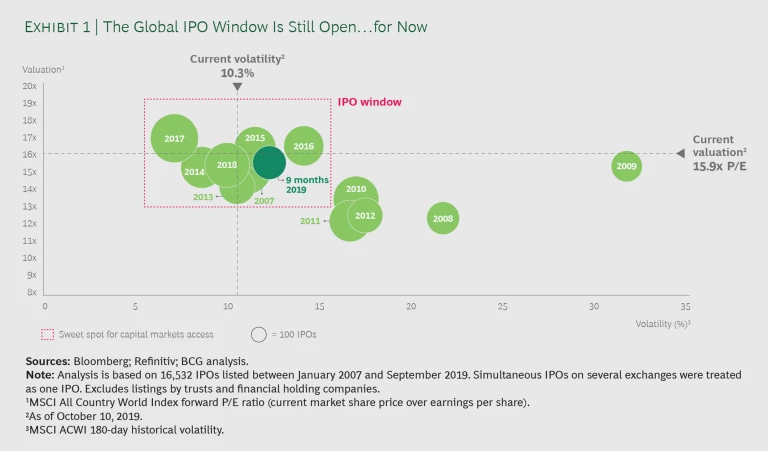

The global IPO market still appears to be in the sweet spot for companies wishing to publicly list, even if conditions are not quite as favorable as they were in the golden days of 2017, when IPO volumes attained levels not seen since before the 2008–2009 financial crisis and volatility reached a low for the decade. In fact, current trading conditions are not dissimilar to those found in 2014 through 2016, a time when the IPO window was wide open, with upward-trending valuations and moderate volatility. (See Exhibit 1.)

High Volatility Characterized the Market in 2018

Looking back, the year 2018 was marked by higher stock market volatility, Brexit issues plaguing European politics, and a continuing US-China trade war. Although global IPO proceeds increased 8% over 2017, the number of IPOs launched during the year declined by a surprising 15%. This drop reflected a trend toward fewer but larger deals, as was also seen in the global M&A market.

In addition, global valuations experienced some compression in the last quarter of the year, with the MCSI All Country World Index price-earnings ratio (P/E) declining 17% from fourth-quarter 2017, signaling a potential cooldown in the market and a contracting IPO window. Nonetheless, a surge of mega IPOs from unicorns (privately held startup companies valued at more than $1 billion), such as Xiaomi, iQiyi, Dropbox, and DocuSign, helped push 2018 proceeds above those of the prior year.

Mega IPOs Buoy 2019

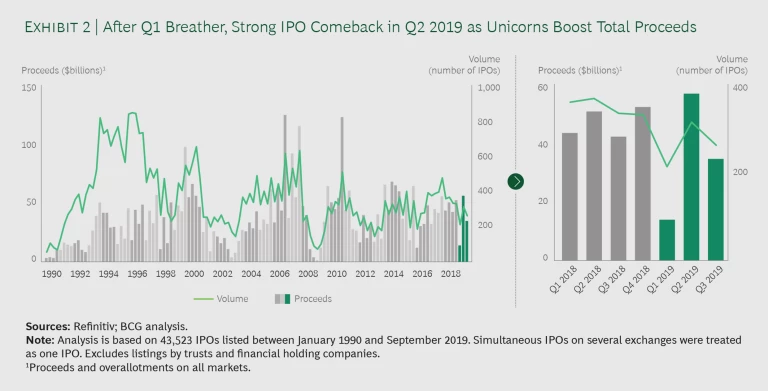

Market softening initially increased in 2019, with just 213 IPOs launched in the first quarter, compared with 359 in first-quarter 2018. After this quiet start to the new year, however, the launch of several long-awaited mega IPOs, such as Uber, Trainline, and Lyft, buoyed the market, as did the relaunch of postponed 2018 listings such as Traton and Pinterest.

Partly as a result, second-quarter volumes increased by 50% and IPO proceeds quadrupled against quarter one. (See Exhibit 2.) Average proceeds per IPO in the second quarter reached $181 million, more than 30% higher than in second-quarter 2018. Valuation levels also partially rebounded, with the latest MCSI World Index P/E up 20% from its fourth-quarter 2018 trough. And while the market for mega IPOs cooled slightly in the third quarter, reducing overall volumes and proceeds once again, it nonetheless remained well above first-quarter levels.

Tech Unicorns Lead the Way

Just as occurred in late 2018, almost all recent mega IPOs have been listed by highly respected tech unicorns with well-known names. Although IPOs in traditional sectors such as industrials and materials lagged during the first nine months of 2019—down from 30% of total IPO volume in 2017 to only 20%—listings by tech players made their largest contribution since 2004, reaching 20% of total IPO volume and an impressive 31% of overall proceeds raised. By comparison, tech IPOs in 2004 generated just 16% of total proceeds, even though they accounted for a similar share of volume as they do today.

Although IPOs in traditional sectors lagged during the first nine months of 2019, listings by tech players made their largest contribution since 2004.

Why did these IPOs generate such unusually large proceeds? As discussed in our 2018 report, venture capital (VC) backing appears to boost investors’ confidence in a listing, validating the claims laid out in the business plan and equity story. This may give VC-backed companies a higher likelihood of receiving a premium valuation than other companies. And the size of this premium is attractive enough that owners have sometimes accepted a public “down round”—offering shares below the price of their most recent private-financing round—while the IPO window remains open, rather than attempting to raise further capital in a private setting.

An interesting example in this context is WeWork, which, up until shelving its IPO plans in October because of corporate-governance issues, was reportedly seeking a valuation as low as $10 billion to $12 billion. This would have represented a discount of 75% to 80% on the $47 billion valuation the company had achieved from its round of private funding in January but would still have meant an attractive multiple of six times sales—stronger than the multiples at which the tech sector is currently trading.

Despite the Robust Market, IPO Results Are Mixed

In spite of these strong results, when we look at the top ten mega IPOs of 2019, we find mixed performances following their listings. Some exhibit strong share price growth, but others show lackluster performance. Trainline, for example, which listed at £3.50 in June 2019, had climbed 19% to £4.17 as of October 31. Meanwhile, Uber, which listed at $45 in May 2019, had fallen 30% to $31.50 as of the same date. This performance disparity arose despite the ongoing resilience of IPO market activity and the loss-making status of both companies at the time of listing.

When we analyze these post-IPO performance disparities more closely, we find that motivations for listing may hold the answer, as many of the successful mega IPOs of 2019 were attempts by VC funds to generate a means of exit, with no new capital raise.

Many of the most successful mega IPOs of 2019 were attempts by VC funds to generate a means of exit, with no new capital raise.

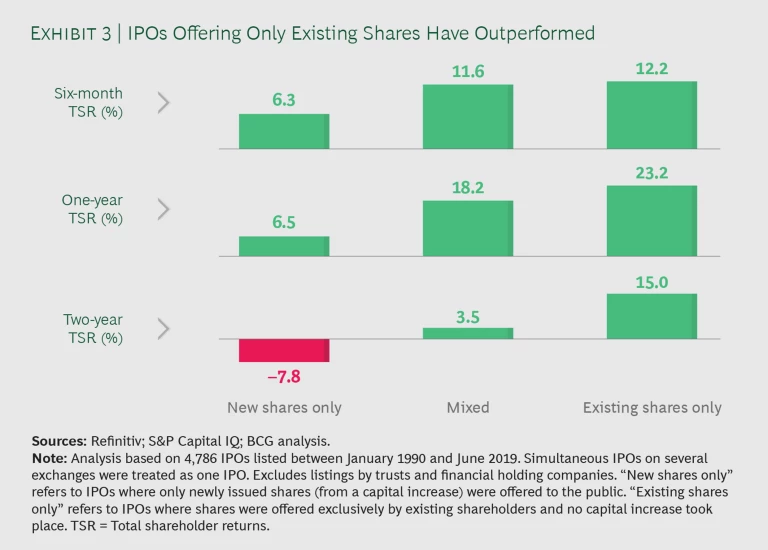

To better understand this link between IPO motivation and performance, we looked at past IPOs as well, analyzing the postlisting performance of 4,786 IPOs completed between January 1990 and June 2019 on a variety of exchanges. The results are clear: companies exiting existing shareholdings have yielded a far more positive total shareholder return (TSR) on average than those attempting to raise new capital.

Companies List for Reasons Beyond New Capital

It would be a misperception to say that companies undertaking an IPO are looking primarily to raise capital. In fact, just a third of the IPOs over the past five years have consisted of new issuance only, and only about 50% of proceeds raised were from the issue of new shares.

So, what might motivate owners to pursue a costly public offering, if not fresh funding?

Liquidity or an Exit Pathway. In an environment where interest rates are low and private equity and VC investors are cash-rich, companies have less impetus to raise new capital through equity. Instead, an IPO becomes much more a means to create a liquid equity market and to fully or partially exit an existing investment.

Corporate Carve-Outs. Large conglomerates are always engaging in portfolio management. An IPO is a pathway for these giants to monetize their assets and make business units independent while uncovering some of the value that is typically masked by the conglomerate structure.

Future Acquisition Currency. Once a company reaches a certain scale, going public provides the opportunity of using liquid stock to fund rapid inorganic growth.

Market Validation. An IPO can provide a true acid test of market value and give additional credibility when representing the business to potential customers and employees.

Exit IPOs Outperform

Business owners might assume that if an issuance is priced at an appropriate level, the reasons for going public shouldn’t affect the future performance of the equity. Yet we clearly found a stark contrast: IPOs not raising any fresh capital outperformed those listings for which fundraising was at least a part of the reason for going public. Over the 12-month postlisting period for each of the IPOs we analyzed, the TSR averaged 23.2% when only existing shares were issued but just 6.5% when the listing was a pure capital raise. These results were consistent across multiple time horizons: whether 6 months, 12 months, or 24 months postlisting, IPOs that involved raising new capital underperformed those in which no fresh capital was raised. (See Exhibit 3.)

The differences are likely due to the signaling effects associated with the nature of a public listing: if the listing seeks to raise new capital, investors will expect the capital to be used to generate value-accretive growth, requiring the owners to create a persuasive equity story and follow through. If the growth postlisting doesn’t appear credible, the market penalizes the stock.

Perhaps unsurprising, we also find a strong inverse relationship between postlisting performance and the proportion of new shares in the IPO: a higher proportion of new share capital issued correlates with lower TSR performance. The higher the proportion of the capital raised in the IPO, it seems, the more investors scrutinize the use of the proceeds.

Four Factors Exacerbate the Differential

We find that four important characteristics can exacerbate the performance disparity between capital-neutral and capital-raising IPOs. These attributes help abate (or intensify) investor concerns both pre- and postlisting.

Growth Momentum. The market appears to be highly skeptical of the ability of slow-growth businesses to generate a return on the proposed new capital when asking for additional funding—but is indifferent when no new capital is sought. For a fundraising IPO, prelisting revenue growth is typically an important determinant of its relative performance: when companies are raising new capital, those with weak growth momentum (below 3% annually) at the time of listing have generally performed significantly worse, at an average 1.7% TSR, than those with stronger momentum, which came in at an average 11.3% TSR. But we find that growth momentum makes much less difference when companies aren’t seeking new capital. In fact, the TSR of capital-neutral IPOs averaged 23.3% for high-growth companies and 26.4% for low-growth companies.

Deal Size. The relative underperformance of IPOs involving a capital raise has been more substantial for smaller transactions. On a one-year TSR basis, IPOs larger than $1 billion that were raising new capital underperformed those not seeking new funds by 2.2%, while deals below $250 million underperformed by a surprising 21.2%. This differential may indicate that larger companies are able to invest more in upfront preparation and building a solid IPO narrative than are smaller issuers, which helps convince investors that the company knows how to use the proceeds and can realize the benefits. And larger companies—by definition—have already proved that they know how to invest capital in order to achieve scale, providing further credibility to investors.

Free-Float Percentage. The proportion of the company that is being floated appears to be a key determinant of the performance disparity between capital-neutral and capital-raising IPOs. Listings that are focused on raising capital typically outperform capital-neutral IPOs when a smaller proportion of the company is floated. This may be because investors place less scrutiny on the use of new capital when only a small portion of the company’s value is at stake. In contrast, listings that consist mainly of existing shares generally outperform capital-raising IPOs when the majority of the company (particularly 50% to 75%) is listed. We believe this phenomenon reflects investor preference for anchor investors to give up their majority control in an IPO exit but retain some skin in the game in order to provide confidence in the listing.

Industry Sector. Investors may be unconvinced of certain sectors’ ability to create value by investing new capital. Capital-raising tech companies appear to have particular difficulty in this respect, at least over the medium term, underperforming tech companies not seeking new funds by 35.3% on a 12-month TSR basis. And tech companies are followed closely in this respect by media and telecom companies, whose capital-raising IPOs have underperformed those not seeking new funds by 27.0%. In contrast, energy, power, industrial, materials, and consumer businesses raising capital have not underperformed as badly.

These results suggest a direct link between TSR disparity and the nature of a sector’s asset base. For sectors with relatively tangible assets, such as energy and industrials, the TSR difference when raising capital versus remaining capital neutral is rather small. Meanwhile, industries with a greater proportion of intangible assets—media, telecom, and tech—tend to underperform more significantly when raising capital. From this, we hypothesize that if a company is planning to raise capital to invest in less tangible assets such as intellectual property or technology, it will need to provide crystal-clear communications about how the IPO will create value for shareholders in order for the stock to perform.

Growth Is Critical to High Valuations

In addition to mega tech IPOs, much of the recent IPO activity has included highly anticipated listings by startups that have popular brands across various nontech industries, all backed by well-known VC funds. Despite incurring heavy losses, many of these companies are valued at impressive double-digit revenue multiples, either by the public or in recent pre-IPO funding rounds. Investors are valuing these companies like tech giants from a bygone era, although the companies operate in more traditional sectors such as food and pet supplies.

Investors are valuing some startups from more traditional sectors such as food and pet supplies like tech giants from a bygone era.

So, what lies behind their high valuations? Apart from VC ownership, our findings reveal one recurring theme in the equity research covering these stocks: growth. But not just any kind of growth. The type of growth that drives these premium valuations tends to be:

- Almost exponential in magnitude

- Delivered by mega trends

- Fueled by the disruptive nature of the business

- Sustainable in nature

For companies exhibiting this type of growth, the market appears to be willing to overlook their loss-making status and reward them for their prospects. Food manufacturer Beyond Meat, for example, is expected to generate a 52% revenue CAGR over the next two years, far outpacing the broader food products sector (6%) and even the tech sector (10%). The impact on the stock’s valuation is clear: Beyond Meat currently trades at an enterprise value to forward-revenue multiple of about 12 times sales, while the food products sector commands a multiple of only 2 times sales and the tech sector trades at 4 times sales.

While IPOs that abstain from raising capital have outperformed on average, the success of Trainline and other fundraising listings proves that investors are still attracted by powerful growth stories. In fact, although the debt market remains wide open and offers inexpensive financing options, the number of IPOs seeking to raise new equity capital increased in the first half of 2019, with 72% of IPO proceeds taking the form of fresh funding. The Americas, the Middle East, and Africa accounted for most of the IPOs involving the issuance of new shares, with Asia-Pacific and European companies less likely to seek fresh capital. This uptick in IPOs pursuing new funds suggests that many companies may be rushing to raise capital before a potential recession—and possibly to support new M&A deals during the downturn.

Nonetheless, business owners looking to the IPO market to raise capital should embark on the journey well aware of the difficulties. Even blue-chip unicorns are not always successful, and smaller companies looking to raise new capital have had an especially hard time postlisting.

Assuming they do proceed, companies therefore need to deliver a powerful equity story demonstrating that the fresh capital they raise will be used to generate value-accretive growth. We reviewed the investor communications of select loss-making companies that have successfully entered the public markets since 2016 while raising fresh capital and, on the basis of their results, we believe the story should include three critical elements:

- Demonstrate a successful growth trajectory. Companies should articulate any historical revenue acceleration, given that exponential growth in the past is evidence of an upward trajectory and path to profitability. They should also show that their unit economics work. For example, a positive gross margin indicates that growth can make up for losses in the medium term. And small success stories, such as successful pilot projects, can provide evidence of longer-term viability.

- Prove the ability to deploy funds for growth. Investors will want to see a convincing vision for the use of funds, clearly showing how proceeds from the IPO will fuel further growth. In addition, the vision should include the potential for cost savings—not just from economies of scale but from reductions in fixed costs as well. Companies can put a quality seal on this vision by securing a well-recognized anchor investor.

- Showcase the sector’s growth potential. Investors need to see demonstrable market growth. Mega trends propelling the relevant market reassure investors that demand is increasing for the products and services the company offers. Investors also need to understand the market structure, including specific market dynamics, such as winner-takes-most structures, that could create temporary anomalies in the business plan. Finally, companies should disclose any dynamic customer development because strong revenue growth from new customer groups will highlight the success of the company’s customer acquisition initiatives.

While the IPO window remains wide open, companies tapping the market so far in 2019 have experienced mixed performances postlisting. Looking forward, therefore, those raising new capital over the next few months are also likely to face TSR headwinds and close investor scrutiny. Remaining capital neutral may be beneficial; however, it will not be a guarantee of a successful listing—nor will raising new funds be a death knell. Rather, companies using an IPO to raise capital will need to create a powerful equity story, demonstrating growth while addressing key investor concerns related to growth momentum, deal size, free-float percentage, and industry sector.