Despite a long economic expansion cycle, most corporate and investment banks (CIBs) have not recovered from the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Tighter regulation, unfavorable interest rates, and stubbornly high costs have left many banks grasping for ways to fund needed investments. At a time when customers are looking for more innovative offerings, and with market stressors likely to intensify, owing largely to the COVID-19 crisis, CIBs are at a critical juncture. They can either continue with the status quo and wither, or they can commit to reinventing how they operate.

We recommend the latter course, not simply because it is the surest way to survival. CIBs that address systemic flaws in their current business and operational models will do more than simply stanch the bleeding: they will revitalize their positions within the broader industry. CIBs that take three actions can increase top-line revenue by 5% to 10% and productivity by 10% to 20%:

- Target high-value products, intellectual property, and customers

- Convert to a customer-centric operating model

- Work within integrated, agile teams

In this way, CIBs can once again become significant contributors to bank growth.

This report is the second in an ongoing series designed to help senior banking leaders prepare for the coming decade. A BCG 2019 report, The New Reality for Wholesale Banks, examined the forces rocking the commercial, corporate, and investment banking market. Here, we focus on the CIB divisions hardest hit by the ongoing disruption, so that executives can rechart their paths to sustainable and profitable growth.

CIBs that address systemic flaws in their current business and operational models will be revitalized.

With Survival at Stake, Tactical Optimization Approaches Have Run Their Course

Buffeted by rising risk costs, deteriorating loan margins, and tough capital requirements, CIBs face severe challenges. Although double-digit returns were common for banks before the global recession from 2007 to 2009, only a few institutions have achieved anything near those levels since. After-tax returns on regulatory capital (RORC) remain around 10% for corporate and investment banks globally—approximately 20% to 30% lower than their precrisis levels. The figure for second- and third-tier institutions is likely even lower, since the global average is inflated by the relatively strong performance of US banks.

Most CIBs have pursued numerous tactical, and sometimes structural, cost-cutting and operational efficiency measures over the past decade to address these pressures. (See “CIB Optimization.”) Although these efforts were an appropriate response in the immediate postcrisis environment, the gains have proved to be short-lived, with only the largest banks succeeding in scaling these measures into sustainable performance improvements.

CIB OPTIMIZATION

CIB OPTIMIZATION

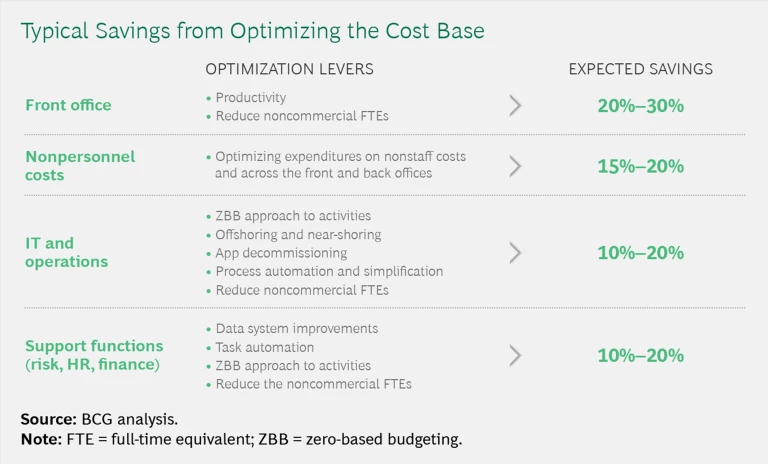

Traditional CIB optimization measures rely on revenue enhancement, cost reduction, and risk-weighted asset (RWA) levers to improve performance. These tactical and structural changes can be implemented fairly quickly, often within 6 to 12 months. As quick fixes, they can give banks needed momentum, close critical performance gaps, and generate savings that can be used for more transformative changes. (See the exhibit.)

Generally, these optimization levers can be grouped into three main categories:

- Revenue-enhancement programs to increase market penetration by selling to new clients, increasing sales to existing clients, and selling to clients at higher prices.

- Cost-reduction programs to improve productivity in the front office (by adjusting client load and segmentation, recombining sales and trading teams across various asset classes, and reducing non-client-facing administration time), in support functions (by implementing data system improvements, zero-based budgeting, and task automation), and in IT and operations through app decommissioning, automation, and offshoring and near-shoring. Although optimization initiatives can yield average savings of 15% and 25% in the aggregate, these returns may not be enough in the long run to help CIBs offset other pressures.

- RWA reduction programs to optimize the balance sheet by reducing exposure size, improving utilization, and increasing velocity.

Traditional CIB optimization focuses on improving the existing organization as is instead of making changes at the root level, which could help banks address systemic issues. The resulting surface-level fixes do not prepare banks to compete effectively in the intense, rapidly changing environment they now face. Global powerhouses have been one exception. Their large balance sheets and reach have buttressed them from some of the external market shocks and given them the ability to invest in longer-term transformational efforts and change their ways of working. Smaller tier two and tier three players have no such cushion. In an effort to compete with large banks, they must spread their limited budgets over many different products. Meeting their day-to-day requirements often leaves very little funding for strategic investment. With CIBs thinly spread and subscale across products, sectors, and regions, resorting to traditional optimization plays will result in their falling behind across the board.

Moreover, with hurdle rates sitting at approximately 15%, the stark reality is that few tier two and tier three divisions can cover their costs of capital. If they are to remain viable, CIBs must reinvent how they operate.

To remain viable, CIBs must reinvent how they operate.

A New, Customer-Centric Path to Growth

Too many regional CIBs are still attempting to be all things to all people and preserve optionality, with the result that they are not serving anyone particularly well. Prioritizing product and regional breadth instead of customer centricity makes banking divisions vulnerable on a number of fronts.

The first is that the investment required to maintain a competitive standard on a wide array of offerings—as diverse as equities and foreign exchange, international account management and payments, and trade finance—is simply too great. In addition, saddling CIBs with a large infrastructure adds weight, slowing banks down when they need to move faster and making them more susceptible to system shocks.

The second reason is that competitive dynamics have shifted. Banks used to be the primary gateway for customers. Digitization, however, has opened up the value chain, allowing challengers to compete with niche services and utilities that loosen banks’ hold on the overall customer relationship.

For example, new players are targeting areas that investment banks once dominated, and they are doing so in two ways: by developing specialized technology to help participants in bond and equities markets improve workflow and liquidity management, and by providing integrated data aggregation, pretrade information analysis, and execution facilitation. Banks that continue to center their approach to market on products will find themselves fighting on too many fronts over too many regions. Moreover, attempting to compete across an extensive catalog will invariably mean starving the products and initiatives with which CIBs have the most credible chance to differentiate and lead, thus eroding the scale they need to remain viable and leaving them without the bench strength and brand awareness to succeed in any one.

The third, and perhaps most important, reason is that customer expectations have changed. Given that the service provider ecosystem is becoming more crowded, and treasurers and finance teams are managing a wider set of responsibilities, CIB customers are looking for their banking partners to act as trusted advisors who can provide tailored advice, reduce complexity, and smooth execution. They want partners that excel not only in their area of expertise but also in service. CIBs have a unique advantage relative to financial-technology companies and other emerging attackers in the form of longstanding customer relationships.

To address these factors, CIBs must fundamentally change the way they operate. They need to take a hard look at traditional value drivers and revise their business models accordingly. To win in the decade ahead, CIBs must become client centric, efficient, and agile, focusing on a select number of high-value areas and applying digital practices and integrated processes to work smarter and leaner. BCG research has found that clients continue to trust banks more than other third parties. CIBs should press that advantage by reinventing how they structure their organizations to deliver consistent, customer-centric service in every interaction. These changes will allow banks to serve as a solutions gateway and establish a critical beachhead for growth in the years ahead. Regional CIBs that commit to making such changes could achieve a cost-to-income ratio of 40% and a return on equity above 15%. These gains will far outweigh what they could achieve through traditional optimization methods and deliver the improvements needed to stay viable.

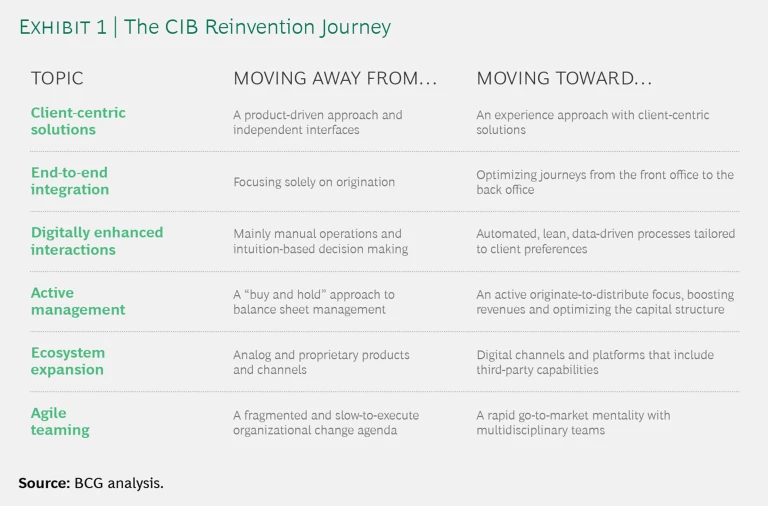

Specifically, we believe the CIBs need to shift from outdated ways of working toward ones that can help them respond more efficiently and strategically to customer and market opportunities. (See Exhibit 1.)

Six Ways for Struggling CIBs to Improve Performance

CIBs that focus on the needs of their high-value customer segments; back areas in which to lead that are aligned with the core strengths of the bank at the group level; and build an integrated and nimble structure can dramatically improve the performance of their top and bottom lines, creating a more prosperous and sustainable future.

By taking a structured approach to reinvention, guided by the following six actions, banks can not only reduce the risk of transformation but also achieve transformational returns.

By taking a structured approach to reinvention, banks can achieve transformational returns.

Refocus the portfolio and footprint. CIBs that stubbornly insist on maintaining a broad portfolio must let go of the old notion that doing so will protect and deepen client relationships, in particular when it comes at the expense of sacrificing leadership in areas and businesses in which they have a right to win. The most successful CIBs will refocus their businesses in three ways:

- Simplify their customer base. Banks need to take a detailed look at the current and projected profitability of their existing customer base. They need to identify segments that have the strongest growth potential and flag low-value accounts that are not delivering the expected returns and are receiving a higher level of service than needed.

- Prune noncore product offerings. A detailed business and market analysis can help CIB leaders identify underperforming or long-tail products that the bank is unable to turn around because of deficits in reach, expertise, or resources. Trend data can highlight emerging opportunities as well as those areas in which customer appetite may be waning. Exiting products with weaker prospects can allow a bank to direct resources into areas where it has strong, strategic opportunities. For example, a CIB that decides to focus exclusively on corporate clients might keep its credit trading desk, given the importance of debt capital markets for corporate clients, but trim back some money markets and fund administration, since these products are noncore for corporate clients.

- Realign and consolidate operating and coverage models. With scale critical to long-term viability, tier two and tier three players need to examine their operating footprints to see where they can consolidate to optimize their reach and resources.

Refocusing can involve painful shifts that challenge longstanding business and cultural norms. Leaders can be reluctant to make changes that might result in a short-term hit to revenues; and product owners, sellers, and others may resist relinquishing client ownership and change segmentation and coverage practices. CIBs need to address such concerns with a thoughtful business and change management program. Quantitative analysis can help build support. For instance, we find that when business leaders see the cumulative investment required to maintain underperforming products and the downstream implications of underinvesting in high-growth areas, they are more likely to support jettisoning lower-value offerings and client relationships. Establishing an independent unit dedicated to off-boarding clients and winding down products can also help to expedite change and manage the inevitable tradeoffs. Incentive structures, too, need to be reviewed to ensure that they encourage desired behaviors.

Put the client at the center of the model. In an industry where the client-bank relationship is a core driver of success, the accelerated pace of technological change is forcing CIBs to rethink the way they enforce greater alignment between their operating models and customer expectations and needs. For many CIBs, a lack of effective coordination between product and sales and across the delivery and service functions has created a disjointed experience for customers and diminished growth opportunities for banks. With 40% of treasurers ranking quality of service as their most important bank selection criterion, the quality of the customer experience is becoming a make-or-break factor in bank profitability. To succeed in a more demanding environment, CIBs need to reorganize in two ways:

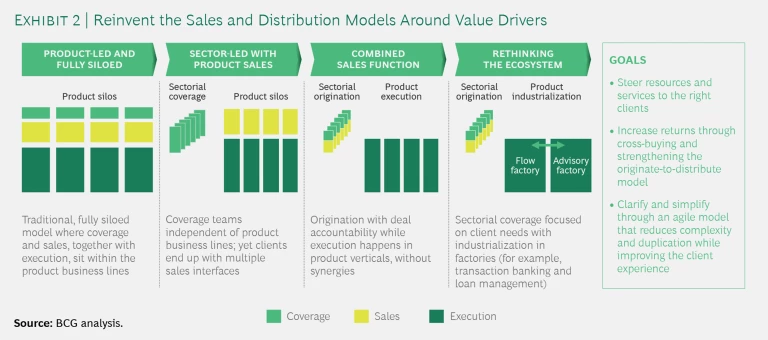

- Align the product and sales functions. In most CIBs, product and sales teams work at arm’s length from each other, an arrangement that results in the duplication of activities and a lack of clarity about who owns the overall client relationship. To get around these issues, CIBs need to reinvent the sales and distribution model—moving from product- and sector-led teams to a combined sales organization with sectors centered on client needs. Banks can better align coverage and sales by collocating sales and relationship managers, either in the office or through virtual teams. (See Exhibit 2.) Embedding these two functions together can reduce the silo-based thinking that has typically predominated and allow banks to put customer needs first, with tailored recommendations that look across the product portfolio. Delivery factories, designed to support a specific set of products (for example, a flow factory focused on transaction banking and day-to-day management, or an advisory factory dedicated to providing specific client solutions) can help banks use their financial and human resources in a more focused way, speeding innovation and execution. In addition, banks should create a dedicated distribution capability much the way they do with the origination side of the business. Devoting specific resources to distribution would improve balance sheet velocity and returns.

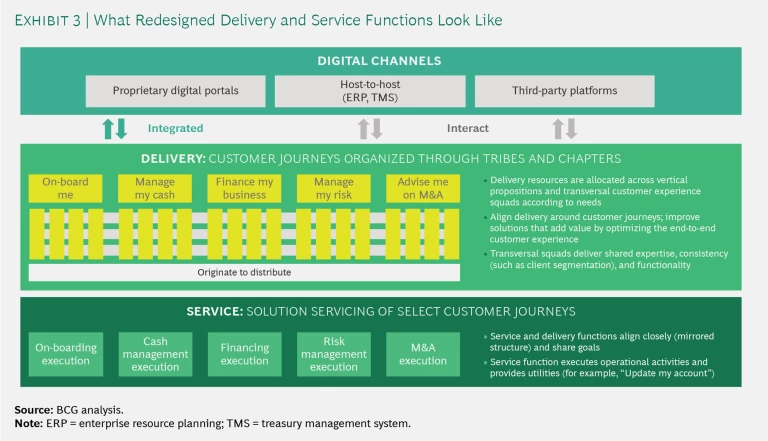

- Redesign processes on the basis of customer journeys. Too many banks have outmoded processes that require significant manual input and operational handoffs. Some banks have turned to automation as a cost-saving effort, but that often adds cost and complexity. To generate the performance benefits they need, banks should step back from focusing on individual processes and look at the end-to-end customer journey instead. By taking this view, CIBs can examine the entire sequence of actions needed to complete a given activity and then see where advanced technologies and automation could have the greatest impact. We recommend that banks focus on a small subset of journeys to start. On the delivery side, we recommend that banks create dedicated vertical teams to design and optimize customer propositions and horizontal teams that deliver either shared functionality (such as SWIFT payments) or shared expertise (such as pricing). The services unit should be restructured to execute customer solutions using automated and lean delivery, with shared utilities that serve multiple customer journeys. These shifts do not require adding more people. Instead, journey alignment allows banks to bring the right people together across the IT, product, operations, risk, and front-office functions. (See Exhibit 3.)

Explore partnership opportunities. Regional CIBs face growing competition and commoditization by digital entrants. Because digital natives generally have lighter infrastructures and a lower cost basis, they can sell their offerings at attractive price points. Rather than attempting to beat digital natives at their own game, regional CIBs can opt to create partner ecosystems to fill critical capability and service gaps in their portfolios. Strategic partnerships could also help CIBs lower their cost structure. Examples include:

- Outsourcing some or all of a bank’s IT and operations to ecosystem players, such as security services firms, to channel resources toward activities that add more value.

- Creating a shared-services model with other regional CIBs to pool IT and staffing. These partnerships can include financial players as well as IT leaders (such as Microsoft) and platform players (such as SWIFT).

- Forging strategic partnerships with proprietary or principal trading firms (PTFs) to combat market share loss in high-frequency trading. (See “Teaming Up with PTFs.”)

TEAMING UP WITH PTFS

TEAMING UP WITH PTFS

CIBs have been losing ground to proprietary or principal trading firms (PTFs) that specialize in algorithmic and high-frequency trading. These entities have been able to gain share rapidly in market-making and execution services, particularly across highly electronified asset classes. PTFs tend to be more flexible than CIBs. They can expand into new regions, asset classes, and services quickly, and they face fewer regulatory and capital requirements (because trades are hedged immediately). Where banks have struggled to manage costs, PTFs have used their superior technological capabilities to deliver better service more cheaply.

Rather than compete with PTFs, some CIBs are choosing to form strategic partnerships with them. These partnerships can take different forms. Some cover risk only. Others encompass the more difficult task of building client relationships as well as operations and services. In 2016, JPMorgan Chase partnered with Virtu Financial to increase the efficiency of its US treasuries trading in the high-frequency interdealer market. Their arrangement took advantage of JPMorgan’s strong client relationships and Virtu’s best-in-class trading software. Similarly, in 2017, BNP Paribas partnered with electronic market maker GTS for US treasury trading, promising its clients improved pricing, tighter spreads, and greater liquidity. Since the collaboration, BNP Paribas’s market share in this space has grown from 1.5% to 4.0%; and, in 2018, the French lender announced that it was extending the partnership to include US equities.

Work in multidisciplinary, egalitarian teams. In order to provide holistic solutions, regional CIBs need to move away from the status quo, where value generation opportunities are concentrated in a few specific roles—star sellers and traders, or top M&A deal originators, for example—and toward multidisciplinary teams staffed with a wide variety of skills, knowledge, and backgrounds (for example, relationship managers, data scientists, IT developers, and operations experts). Greater collaboration can help banks deliver tailored client solutions faster and more efficiently.

In BCG’s experience, banks that use agile methods and collaborative teaming can generate significant impact and unlock value, especially in their technology investments. For example, by applying agile methods to IT and software projects, thus delivering the right features and capabilities, one bank sped delivery by 30% to 50% and boosted production by 10% to 20%.

Prototypes and pilots are helpful ways for banks to begin developing their agile blueprint. Showing proof of concept in select high-value areas serves to overcome resistance to change and builds support, creating excitement in the organization and converting skeptics into promoters.

Embrace digital and data. CIBs need to decide whether to transform their core banking systems as an IT hedge strategy or to create a standalone challenger business as a revenue play. Both approaches have tradeoffs.

While the creation of a completely new bank is appealing, since it allows CIBs to take advantage of the latest technology and avoid legacy issues, building a new bank is a massively complex undertaking that can take years to scale. On the other hand, CIBs know all too well that a traditional IT transformation can also take years, and the results may still lag customer and user expectations. Determining which of the two models to pursue requires assessing a bank’s overall business strategy, market position, risk tolerance, and current resources and capabilities.

Both models require CIBs to make smarter and more strategic use of data. That starts with capturing, standardizing, and storing relevant data in a single, easily accessible source, such as the cloud. Education is also key. Front-office and back-office personnel must be trained to use data-driven insights in their work. Small training teams, led by data scientists who specialize in drawing insights from data, can help. These teams can train relationship managers and others in the use of analytics to originate new business, increase client satisfaction, and boost productivity.

Prioritize sustainability. Employees expect companies to do more to help address societal and environmental challenges as part of a bank’s value proposition. Younger workers, especially, tend to look for employers that prioritize climate change issues. CIB customers, many of whom are taking steps to improve their own company’s sustainability credentials, also want their banking partners to show similar commitment, and many investors now routinely consider environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in their decision-making processes. Regulators and governments are also inching ever closer to mandating minimum-sustainability guidelines for the banking sector.

BCG estimates that sustainability-led businesses will contribute roughly $200 billion of the nearly $700 billion in the global wholesale banking revenue pool from 2019 to 2025. The key challenge for many CIBs, however, is figuring out how to build an effective sustainability strategy to capture this opportunity. Some growth will occur organically through the lending portfolio. To spur the vast remainder, however, banks will have to develop sustainability-led value propositions that go well beyond the limited ESG investing and green-bond-style products seen today.

The World Wildlife Fund in Australia, for instance, launched a global blockchain platform that lets suppliers and stakeholders track goods, such as sustainable fish, along the supply chain. Some banks have started creating their own variants to demonstrate ESG practices in action. For example, HSBC created a supply chain finance program with Walmart that pegs a supplier’s financing rate to their sustainability standards.

Looking ahead, CIBs could explore more innovative sustainability propositions that take advantage of digital platforms and advanced analytics. Examples include transactional analytics that optimize supply chain carbon emissions, corporate card solutions that reward sustainable expenditures, and digital ecosystems that certify and connect sustainable buyers and suppliers.

CIBs must make smarter and more strategic use of data.

Coming to grips with the changes convulsing the banking sector around the world requires nothing short of reinvention. While that may seem a fearsome prospect, our experience shows that for banks that are willing to commit, the returns can more than make up for the short-term discomfort involved. By following the approach outlined here, banking leaders can begin their transformation journeys confident that they have the guideposts they need to succeed.